aaajiao: 'This is my understanding of what a metagame is'

Courtesy the artist.

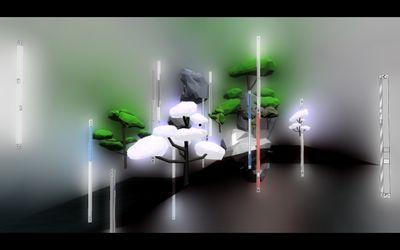

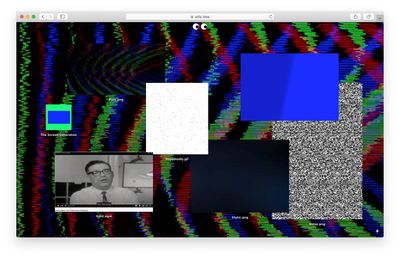

Courtesy the artist.

aaajiao makes note of the fact that he was born in the year of George Orwell's novel 1984 (1949), in which the concept of Big Brother was magnified through a dystopian lens.

The synchronicity frames the trailblazing path that the artist, activist, and programmer has charted through the art and tech scenes in China, creating a practice that consistently probes the depths of the online world and its implications for society.

aaajiao is the online handle for Xu Wenkai, who coined the name in the years he downloaded mp3s from Soundseek, and chatroom users clipped his username chromatic_corner to 'A Jiao' (literally in Chinese: corner).

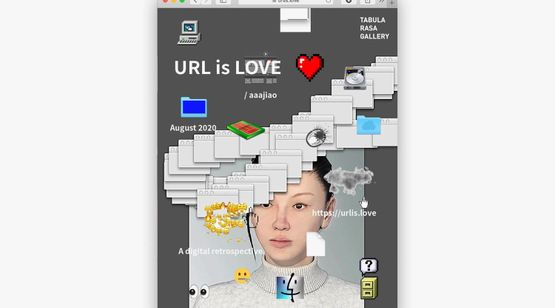

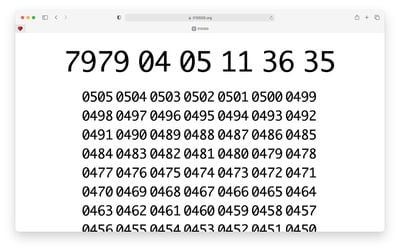

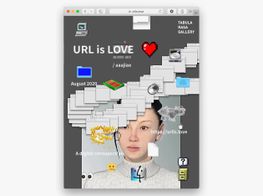

His online interventions, recently showcased with Tabula Rasa Gallery in the 2020 show 2020 URL is LOVE – A Digital Retrospective (1 August–31 December 2021), include the artist's first internet work, 010000.org (2008). The page presents a countdown of ten thousand years—the length of time that curator Li Zhenhua leased a webpage on one of aaajiao's servers—whose start date depends on the location of the user who enters.

Beyond the internet space, aaajiao's spatial installations and objects bring the implications of the virtual world into the real, imploring viewers to contemplate their role as users of a technological superstructure that reduces people to ones and zeros. For Afterimage: Dangdai Yishu, curated by Victor Wang at Lisson Gallery in London (3 July–7 September 2019), the artist's interactive installation 404 (2017) invited viewers to imprint '404'—the error code for lost websites or files—on the gallery walls using ink-sponge rollers.

While Wang linked 404 to 'the continuing era of internet censorship within the so-called "great firewalls" of .cn', aaajiao has stated that he is less interested in censorship as he is in the activation of individual autonomy within an expansive system.

The work, in fact, originated from the artist's plan to film in the Shanghai Futures Exchange server room, which failed. 'This whole experience reminded me of the 404 page, where as a "user", your access is limited', he told curator Song-Min on the occasion of a screening with Arthub in 2019 of the single-channel video, I Hate People but I Love You (2017). 'You do know it exists, but you can't touch it. It only exists in the imagination.'1

In 2010, curator Robin Peckham pointed out that aaajiao was more widely known in China 'for his efforts at organizing and sharing information rather than as an artist per se.' In 2009, two years after graduating with a degree in Computer Science from Wuhan University, aaajiao founded China's first co-working space. Xindanwei was run as a social innovation enterprise until it was named one of the top ten most innovative companies in New York by Fast Company in 2012, yet closed down one year later.

As the artist noted during the project's inclusion in the 2016 exhibition Hack Space curated by Amira Gad and Hans Ulrich Obrist at the K11 Art Foundation Pop-up Space in Hong Kong (9 November–8 December 2016), he now considers Xindanwei an artwork.2 Given the venture's failure as a business, its original utopianism has evolved to absorb the broader changes in working and creative culture in China, locating the project in the early wave of entrepreneurship that has flourished in recent years amid the country's capitalist boom.

The same foresight can be seen in the 2011 audio installation Poor Mining, an early study on bitcoin composed of sounds of the cryptocurrency's excavation drawn from internet mines in real time, which Hans Ulrich Obrist has described as both futuristic and archaeological.

As Sasha Zhao writes, Poor Mining 'is, in essence, a classroom for the training of new media miners.'3 In the gallery space, a contact microphone collects the noises transmitted to a computer connected to bitcoin internet mines and plays them from speakers, while the artist's username and password are spelled out in neon lights on the wall nearby.

aaajiao has described Poor Mining as the result of thorough research into bitcoin's basic structure both within the frame of the internet and capitalism. He found that the cryptocurrency, despite its proclamations of egalitarianism, violated his understanding of internet justice.

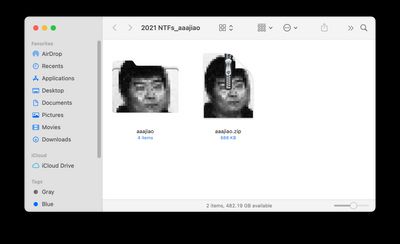

Perhaps it is that violation that led aaajiao to engage with the NFT phenomenon. For NTFs_aaajiao (2020–2021), hosted on the website piecesofme.online, he placed an encrypted .zip file containing four blurred self-portraits that can be downloaded by anyone, but whose contents can only be accessed by a collector who has paid 3 ETH for the password. Yet, in the work's statement, we learn that the password in question 'is aaajiao's common password found in the Social Engineering data, i.e. the password that has been cracked publicly'—a gesture that recalls the artist's open sharing of his bitcoin account and password in Poor Mining.4

That sense of double play, in which a seemingly straightforward work is laid bare as a labyrinthine critique that feels at once accessible and obscure, comes through, also, in the artist's latest exhibition, Deep Simulator, at Tabula Rasa Gallery in London (4 June–31 July 2021). The work was first shown in the project room of Castello di Rivoli Museo d'Arte Contemporanea in 2020, marking the artist's first exhibition at an Italian institution.

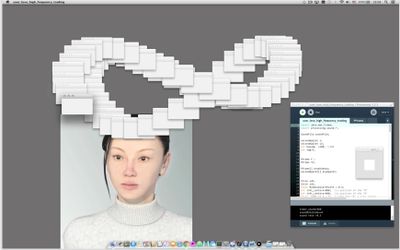

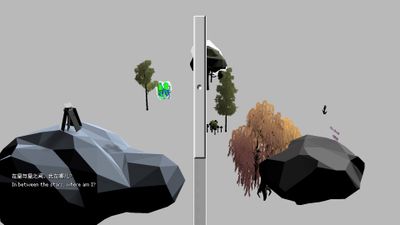

In this conversation, the artist introduces Deep Simulator, defined as a metagame that is available to play in the gallery space as well as to download and play at home, and elaborates on the development of his practice and its attendant critiques on the digital era.

SBFirst, could you define what a metagame is in relation to Deep Simulator?

AIt's a game about the game. This is my understanding of what a metagame is. In Deep Simulator, a metagame is more about the need to constantly pass through the dimensional wall while playing, constantly examining where the player is.

Presented in the exhibition space, the game places the body within a spectrum of real and virtual to create the so-called Deep Wanderer, the protagonist of this metagame, which consists of the player playing the game, the body wandering in the game itself, and the exhibition viewer watching the action.

I think NFTs are a by-product of the crazy rise in tokens caused by the increase in cryptocurrency, capital, and platforms.

SBHow does this relate to the six states of Bardo—a Buddhist conception describing the stages between death and rebirth—that structures the game? And how are these states retrieved by the player via six levels of computational power, as the game outline states?

ADeep Simulator tries to propose an image of a player who can see the truth, but who is also wandering in the game. Six different scenes in the game and the NPCs in them use different computing power, corresponding to six different Bardo states respectively, which is a deliberate treatment to make the boundaries clear, so that the player's wandering or meditation in the game allows perceptions to flow.

NPC stands for Non-Player Character, and relates to role-playing games such as Dungeons & Dragons. It is an internet meme that represents people who do not think for themselves.

In the game, I shaped some of the previous works into NPCs. Each piece of work with computing power considerations are significantly different. In addition to the scene design, computing power performance in the composition of the landscape varies.

Some things are low polygons of models, some are high, and for example, fur is a real-time dynamic hair simulation. This is an intuitive approach, but this also presents only a single vector, so in the scene where the totem is located, there is no landscape. This scene has an infinity of computing power.

SBCould you elaborate on how the Deep Wanderer of Deep Simulator extends from The User that you presented with Leo Xu Projects in 2017 as part of User, Love, High-frequency Trading, and the bot from your 2018 project bot,?

How is Deep Simulator an extension of these gaming formats that interrogate the position of the user, and the user's engagement with others, in virtual space?

AUser, Love, High-frequency Trading is a manifesto that expresses my feeling that everyday life has shaped everyone to become a user, and I try to understand what is happening around me as a user. A video called Column (2017) illustrates this.

In Column, I change a computer system time, whether back to 1979 or forward to 2038, and in each year, a programme written on the column added a part to the structure. I wanted to think in a 'user' way, and I realised that time travel is also experienced as time building.

Bot, is about insight developed through Vipassanā, a Buddhist conception of deep self-knowing and transformation. I think I am seeking that insight from the perspective of the bot. I am a user, so what I am—how I understand the data that surrounds me, or what can be referred to as new memory system—consists of my body and the smart devices that extend from it, as well as the social media that stores my traces.

The player in Deep Simulator is both the user and the bot. The player not only focuses on the self, but tries to see all that is happening, like the climate, enveloping every inch of space.

SBWhile playing, it began to feel like a repetitive loop leading nowhere—sometimes literally, as I'm expelled into the opening page, which seems to function almost like Space (2016/2020): a blank web page with two page navigation bars that lead nowhere.

AThere is some resistance to the game, and I think this is a very unfriendly part of its construction, because it doesn't have any directional guidance. Players need to spend time wandering around in it, doing nothing, or they may turn the game off and go through the day with a sense of frustration, trying to find comfort in everyday life.

I think I want people to remember that they have to observe their own state, and if this is a spiritual approach, it may just be coincidence. I don't think the gaming internet is particularly different from spiritual witch doctors and drugs culture. They all seem to remind us that we have a body while getting rid of it.

SBI am especially interested in the screen from which Cantonese speakers at a protest can be heard. In the game, I'm told to find a Crown Straw to learn more, but I never find it! Is there a Crown Straw to be found? Does this particular section have anything to do with the significance of opening your show on 4 June?

AIt can be found, and afterwards it is possible to enter this scene, in which I reconstructed two previous works, the last media and party (both 2019). The social movement that the player can see is compused using huge computing power, which stands in for propaganda. The computing power can be observed to be changed. The fourth of June is just a coincidence, but of course I would love to open on this day.

SBWhat is the significance of mountaineer George Mallory and his death on 9 June 1924 in this part of the game?

AThe author of the script, Ag, made up some details about his climb up Mount Everest, which I thought was a way of presenting the complexity of a narrative; where understanding the world through social media seems complete, but at the same time, made up. It's real yet absurd.

SBDuring a talk at DLD Berlin in 2017 you told people to refuse being users. You said that to be a user is to be limited, de-individualised, and easily replaceable, which relates to the way you think about the online space as both structure and metaphor for society. Could you expand on your conception and critique of the user in a world shaped by technology?

AIn 2017, I had just finished User, Love, High-frequency Trading, an exhibition with Leo Xu Projects, and I felt a little bit of fear about the trapped authority of technology. I struggled a little bit to make the work, and I think I found a balance in it with my own situation. I couldn't get rid of the user identity for a while, then I tried to redefine it and empower it, and after that I started the attempt to become a player. And from this, came bot,.

SBYou studied computer science at Wuhan University and initially wanted to work in information technology 'to change the world'. How does a work like Deep Simulator reflect this intention?

AI was convinced that a website or an app could change the world, which of course has always encouraged me to try various mediums on the internet. Now I am no longer naïve. The world keeps changing, and all I can do is choose those changes I can empathise with. I believe games are a less fragmented presence of the moment in the context of a high-speed flow of data.

In my research, I found that bitcoin is not a free system. It is dependent on existing resources, including manpower and electricity. This is not a utopia. This is a war of resources.

SBBefore you graduated in 2007, you were active in art and tech scenes in China. Could you talk about those early years, and how you developed a practice as both new media artist and computer programmer?

AI started to make my personal website when I was in high school, and I remember that the one that took shape was a rock music consultation and information website called xarock, and later in college this became cornersound, in 2003.

In 2006, I organised with friends the translation of Régine Debatty's blog, we-make-money-not-art, with the author's authorisation. Through that, I learnt about some sound and new media art. Because of the translation work, I learnt that the computer science and technology I studied could be the basis of my own creations, and I started to make some works from 2006.

SBIn 2010, curator Robin Peckham said that you were mostly known for your 'efforts at organizing and sharing information rather than as an artist', which reflected the launch of Xindanwei in 2009, which you founded: cited as China's first co-working space, which closed down in 2013.

Could you talk about the evolution of Xindanwei? How did you get the idea and what did you learn in building it?

AXindanwei was a utopia and my biggest fantasy about Shanghai at that time. In 2009, we launched Xindanwei with Liu Yan and Chen Xu, which was also the first co-working space in China. We had been operating for four years and staged more than 300 events, including talks, workshops, and small exhibitions, but it became clear to me through Xindanwei what a company is.

We didn't have a chance to get Series A funding, so it was a failed business. When Xindanwei closed, I returned all my attention to my work, but one thing that has remained is that I have been collaborating with friends and I have been using Basecamp to manage the studio and my work projects. That's what running Xindanwei has taught me: to focus. There are no business utopias either.

SBYou now refer to Xindanwei as an artwork rather than a venture, and though you ran Xindanwei in a utopian way, you find its existence as an artwork ironic since it failed on business terms. How did you reflect this formally?

AI organised some of Xindanwei's wreckage into pieces. For example, our client materials of the time were saved in a device that people could copy, so long as they had a USB drive with them. I guess it's a kind of self-flagellation that Xindanwei is not a good business; I really liked this work, although the cost of it is a bit high.

SBYou've said that you don't believe a culture of co-working exists in China, but that Xindanwei was an early example of an emerging creative entrepreneurship. Do you think a culture co-working exists now in China?

AWhen I saw that WeWork was having trouble operating, the corners of my mouth curved upwards. I don't believe in any co-working space, but I believe we've been co-working for thousands of years. At the time, Xindanwei's slogan reflected a new way of working, which I thought was nonsense.

SBLet's talk about Poor Mining. For this early study on bitcoin, which you produced in 2011, you researched bitcoin's basic structure and found that bitcoin violated your understanding of internet justice.

AIn 2011, I made a very difficult decision—difficult probably from today's bitcoin price decision. At that time, I was swinging between whether to mine or create an artwork, so I called a friend. In the end, I decided to create Poor Mining.

In my research, I found that bitcoin is not a free system. It is dependent on existing resources, including manpower and electricity. This is not a utopia. This is a war of resources.

SBHow has your view of cryptocurrency evolved since 2011, and how does the NFT phenomenon fit into your view? It's quite interesting how NFTs act as a kind of intersection between the worlds you engage with: art, the internet, horizontal modes of organisation.

AI think NFTs are a by-product of the crazy rise in tokens caused by the increase in cryptocurrency, capital, and platforms. Art is always the beginning of a good story. When the act of trading itself becomes the value, I think the trading platform and the act of trading become the artwork.

SBI also wanted to ask about the NFTs you released: I see that only collectors who have obtained the password to the zip file through an NFT transaction have access to the tokens, yet you state that the password 'is aaajiao's common password ... that has been cracked publicly'.

Does this mean anyone can effectively obtain your NFT?

AYes, if someone can get the password, they can unzip the file package. This work basically realised that the value of the transaction is not reliable. Exploring the transaction is the value, for art.

SBFrom 1984 to now, do you see everything you do under one umbrella, or do you understand your practice according to the different fields in which you work?

AI'm doing it to become my imaginary self, for myself, for specific people, and for everyone. Maybe it's all an illusion, but I stay put. Some moments can be perfect, but of course, most of life is sparse and fragmented.

SBAs reliance on smart technologies and global interconnectivity increases, what does the future look like to you?

AI look around and never progress nor regress. The future is waiting. At the moment, I am preparing a solo exhibition called I Was dead on the Internet to be shown at a pop-up space in Shanghai in September. It's about being dead on the internet, where I once thought I was raised.

These two years trapped in Berlin, I've watched things growing on the balcony, and followed the daily routine of all my neighbours. While surviving on the internet during this time, I still died on it. The fluttering rustle of bamboo leaves in the strong winter wind erased fingers leaving greasy fingerprints on the screen. Failure, frustration, worthless moments, and thoughts. —[O]

1 Song Min, Interview with aaajiao, Arthub, January 2019, http://arthubasia.org/screening/aaajiao-i-hate-people-but-i-love-you

2 aaajiao, Artist Talk: HACK SPACE, K11 Art Foundation, YouTube, 3 August 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DfwWnv_69lo

3 Sasha Zhao, 'Bitcoin', Leap, 19 June 2015, http://www.leapleapleap.com/2015/06/bitcoin/