La Dotta, la Rossa, la Grassa: the 42nd Arte Fiera, Bologna

Piazza Maggiore, Bologna. Photo: Stephanie Bailey.

As curator Clarissa Ricci noted, Bologna's fair history can be traced back to the 17th century, so the city is no stranger to culture's relationship to money, with a tradition of collecting and patronage that is similarly historical.

Bologna is a city with many names. First, there is 'la dotta' (or 'the learned one') in honour of its university, the oldest in the western world (established in the 11th century), which counts Petrarch, Copernicus, Dante and, more recently, the cult (and controversial) Bologna-born filmmaker, Pier Paolo Pasolini, among its alumni. Its second sobriquet, 'la rossa' or 'the red one', refers to the colour of its mediaeval and renaissance buildings—a colour also associated with Bologna's postwar identity as a communist stronghold. The capital of the industrially and agriculturally rich Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy—one of the wealthiest in Europe, where Ferrari and Lamborghini are both based—Bologna is also known as 'la grassa', or 'the fat one', for its food.

As far as art history goes, Giorgio Morandi was born here. (The Morandi Museum collection is currently housed in the complex of the excellent Museo d'Arte Moderna di Bologna, MAMbo, whose director, Lorenzo Balbi, became the youngest director to be appointed at the museum in 2017.) Morandi's house is a brisk walk from Piazza Maggiore, where the Basilica of San Petronio, one of the largest churches in the world, stands in proximity to the impressive Palazzo d'Accursio, where, as the Palazzo states, 'the city has been governed for a thousand years'. (The Palazzo is home to the municipal art collections and a 1676 Baroque quadratura typical of the Bolognese school—a painted ceiling with illusory perspectives—in the City Council Hall.) The city's fair, Arte Fiera, is one of the oldest of its kind, having launched in 1974. It has since been staged in the same commercial complex, the Bologna Exhibition Centre, managed by the some 120-year-old enterprise BolognaFiere, whose central halls (inaugurated in 1965) were designed by architects Leonardo Benevolo, Tommaso Giura Longo and Carlo Melograni. (Kenzo Tange designed a series of independent halls to add to the BolognaFiere complex in 1972, with additions added to the area in the decades after.)

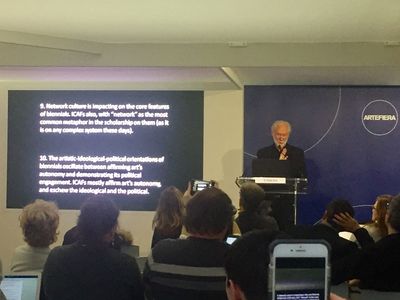

This is the legacy that Arte Fiera's artistic director, Angela Vettese, tapped into during her opening remarks to the conference 'Between Exhibition and Fair: Entre Chien et Loup', staged as part of the fair's 42nd edition this year (2–5 February 2018)—Vettese's second Arte Fiera, having taken on the fair's directorship in 2016. Curated by Vettese with Clarissa Ricci, and organised by Ricci, Cristina Baldacci and Camilla Salvaneschi, speakers included academics Terry Smith and Gwen Allen, and Art Africa's Suzette and Brendon Bell-Roberts.

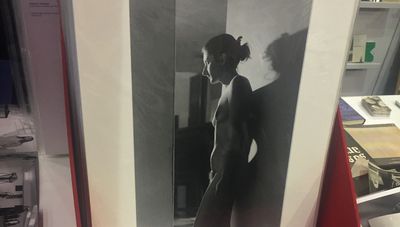

A joint-production between Arte Fiera, the University of Bologna and Università Iuav di Venezia (where Vettese was a lecturer), 'Between Exhibition and Fair' explored the connection between large-scale exhibition-making and art fairs, which inevitably touched on the inextricable link between art and money. As Vettese pointed out, some of recent art history's most radical happenings took place within commercial spaces. In 1977 and 1978, for example, Arte Fiera hosted a daring exhibition programme of performances that included Marina Abramović and Ulay's Imponderabilia (1977), which involved the artists standing naked on either side of the entrance to the Galleria Comunale d'Arte Moderna facing one another so that visitors had to pass between them. (Scheduled for three hours, police shut it down after 90 minutes.)

As Clarissa Ricci noted during her introduction to the panel 'Fairs and Biennials: A Couple or Sisters?', Bologna's fair history can be traced back to the 17th century, so the city is no stranger to culture's relationship to money, with a tradition of collecting and patronage that is similarly historical. There are a plethora of foundations here and throughout the wider region, from the photography-focused MAST Foundation, a non-profit founded in 2013 by Coesia Group president Isabella Seràgnoli, to Fondazione Furla, founded by Furla president Giovanna Furlanetto in 2008, following the launch of the Furla Prize for Art in 2000, in partnership with the Querini Stampalia Foundation in Venice. (The prize was discontinued in 2015.) Heiress Cecilia Matteucci Lavarini, collector of historic couture and modern and contemporary art has a home in the city, as does Gaia Rossi, who has reportedly filled the historic Palazzo Bentivoglio with art by the likes of Alex Katz, Ettore Sottsass, and Davide Trabucco, among others. Luca Cordero di Montezemolo (formerly of Ferrari), the Bologna-born Alitalia chairman with a reported penchant for pop art, is known to frequent Arte Fiera's halls, having once been president of BolognaFiere. All of which supports Arte Fiera's claim that it has been the 'fulcrum of the national art market' and the 'leading national event in terms of sales' in Italy for the past 42 years.

As a whole, Arte Fiera's identity is decidedly Italian. The majority of the 152 exhibiting galleries came from all over the country, from Asti (GalleriaEidos Immagini Contemporanee, showing beautiful abstract paintings by Bruno di Bello and Hans Hartung) to Sarzana (Cardelli & Fontana, showing a varied selection of beautiful mid-20th-century geometric abstract paintings in earthtones by the likes of Manlio Rho, Mario Radice, Aldo Galli, Ideo Pantaleoni, and Renata Boero, alongside contemporary mixed media pieces by Beatrice Meoni and Simone Pellegrini,among others).

Around seven galleries in this year's line-up have spaces both in and outside of Italy. These included TornabuoniArte, where Alberto Magnelli's canvases stood out, and a painting by Giovanni Boldini (Portrait of Miss Concha de Ossa, c. 1888) recalled the excellent show at the Complesso del Vittoriano in Rome last year (Giovanni Boldini, 14 March–16 July 2017); and Galleria Continua, who showed artists such as Shilpa Gupta, André Komatsu and Elizabeth Cervino. (There are eight if you count Contini Art UK, which is related to Galleria d'Arte Contini.) Paris's RCM, Tirana's Gallery on the Move, Düsseldorf's Galerie Voss, Pueblo Garzón's Piero Atchugarry Gallery, and London's Repetto Gallery came from abroad.

But while the gallery list was clearly national, the art on show was global in scope, with Vettese's direction breaking down divisions between the fair's gallery sectors so that they blend into one another—from Main (modern and contemporary) and its sub-section 'Modernity' (spotlighting lesser known histories and movements), to Photo and Solo Show. (The exception was the Nueva Vista sector, curated by Simone Frangi to showcase emerging talent.)

Prometeogallery, participating in the Modernity sub-section, spotlighted photo documentation of various performances by Regina José Galindo, such as Tierra (2013), for which the artist stood in a field while an excavator dug the ground around her. (Galindo participated in documenta 14, as did Mary Zygouri, whose 2017 embroidered work, Metric of Sappho, was also showing in the booth.) Federica Schiavo Gallery grouped geometric abstractions on canvas by Svenja Deininger and Carla Brörmann, alongside equally abstract works on paper by Salvatore Arancio; and Primo Marella Gallery represented Abdoulaye Konaté, He Wei, Ruben Pang, and Joël Andrianomearisoa, among others.

One highlight was Metronom's booth, part of the Photo sector, with photographs by Sanna Kannisto, Taisuke Koyama, Rachele Maistrello, and Christto & Andrew installed on a series of walls painted white, candy pink and baby blue. Christto & Andrew's lambda prints on photography paper feature fresh hyper-pop still life arrangements that burst with colour. Birds of Paradise (2015) hung on a pink wall; the photograph depicts a line of five falcons perched on wooden stands topped with faux grass, with a luminous teal radiating outwards from behind them only to fade into a rich violet. (The artist duo are one half Puerto Rican, one half South African, and currently live and work in Qatar.) Another stand-out was Officine dell'Immagine's solo focus on Nigerian artist Marcia Kure, with collages depicting female and natural forms through a minimal yet considered amalgamation of assembled images.

There was an abundance of historical presentations. Galleria Tega showed pieces by Fernando Botero, Alberto Burri, Lucio Fontana, Christo, Giorgio de Chirico, Paul Klee, Achille Perilli, Mario Schifano, and Pablo Picasso, among a host of others. Here, the pairing of Carla Accardi's Aranciorosa (1965), with characteristic curved lines of fluorescent pink and orange uniformly arranged on a Sicofoil 'canvas'—a clear plastic material the artist often used—with 'Gruppo Uno' artist Giuseppe Uncini's cement and iron wall sculpture Spazicemento no.19 (1955) was notable. Accardi was represented in the recent exhibition at Monnaie de Paris, Women's House (20 October 2017–28 January 2018), with a tent made from the same Sicofoil covered in curved lines, Triplice tenda (Triple tente) (1969-1971); it was created just a few years before the artist's participation in the Ambiente/Arte section of the 1976 Venice Biennale organised by curator Germano Celant, who coined the term Arte Povera. (The Venice presentation proved influential for the movement, it is stated.)

In other sightings, brightly coloured and irregularly geometric paintings by artist, designer, inventor and sculptor Bruno Munari were spotted at Galleria Bonioni Arte, Cardelli & Fontana, Kanalidarte, and Repetto Gallery; an artist whose 'Negative Positive' paintings were made around the time (the great) Peter Halley, whose canvases echo Munari's compositions, was born. (Halley's paintings were seen at Artesilva and Galleria Emilio Mazzoli.) At Galleria de'Foscherari, works by Pier Paolo Calzolari, Claudio Parmiggiani, Giorgio Morandi, Mario Schifano, Gianni Piacentino, Sophie Ko and others were arranged, with Schifano spotted in quite a few booths, including In Arco, where his works were seen alongside a beautiful group of small paintings—little landscapes in rich colours—by the late Salvo.

Biasutti Gallery gave Giorgio Griffa his own booth; mid-20th-century abstract expressionist paintings by Paul Jenkins and Conrad Marca-Relli were the focus of a subtle hang at Galleria Open Art; small Julio Le Parc colour-line paintings were shown in a minimal yet effective presentation organised by Labs Gallery, which also showed Gianfranco Baruchello's illustrative paintings in enamel on aluminium, including a biological deconstruction of the human body and head, What Can Be Done (1970). Meanwhile, a chunk of space at Galleria d'Arte Cinquantasei was devoted to futurist Giacomo Balla's varied practice, which ranged from realist portraits to bright geometric paintings.

Some galleries blended the past with the present. At Mazzoleni, Alberto Savinio's metaphysical painting, Senza Titolo (1930) shone among works by such artists as Piero Manzoni, Alberto Burri, Fausto Melotti and Marc Chagall. Savinio's canvas depicts candy coloured three-dimensional geometric shapes that foreground a bucolic, albeit tempestuous, renaissance landscape. Covering the booth's outer wall was David Reimondo's Instagram-friendly large scale contemporary work, Etimografia (2014–2017), a uniform series of square white lacquered panels each with an ideogram of the artist's making rendered in ink-coated wood.

In other cases, contemporary artists paid homage to some of the greats. Marco Maria Zanin, showing at Spazio Nuovo, references the work of Morandi in the fine art prints on cotton paper that make up his 2015 'Lacuna e Equilibrio' series. These mirror the still life compositions Morandi was known for, this time with arrangements of debris that the artist collected from São Paulo demolition sites. A group of sculptures by the collective The Bounty Killart showcased on Marcorossi Artecontemporanea's outer wall was a crowd-pleaser: editions of small classical figurines updated to suit the 21st Century. In the case of a roman copy of the Discobolus of Myron, or 'the discus thrower', an electric guitar replaces the discus (Guitar Hero, 2016), while a three-dimensional rendering of God from Michelangelo's The Creation of Adam sports a yellow, rubber washing glove and a bottle of spray detergent (Cielito lindo, 2017).

Beyond Arte Fiera's halls were parallel events organised as part of the fair's Polis programme, which saw works by the likes of Vito Acconci, Mario Cresci, Rachele Maistrello and 15 others installed in various public locations and noteworthy buildings around Bologna as part of Polis/Artworks; curated by Angela Vettese in collaboration with Nicolas Ballario. Other Polis projects included Polis/Cinema, curated by Mark Nasha, which involved a screening programme at MAMbo; and Polis/Special Projects: Performing the Gallery, a programme curated by Chiara Vecchiarelli that explored the potential of performance in the 'landscape of the contemporary', as explained in the event's press release.

Around the city, a number of exhibitions were on view, including It's OK to change your mind!—Contemporary Russian Art from the Gazprombank Collection, curated by Lorenzo Balbi and Suad Garayeva-Maleki, at Villa Delle Rose (19 January–18 March 2018). Continuing the Russian thread was MAMbo, which hosted a party during the annual Art City White Night (3 February 2018) organised by BolognaFiere in collaboration with the City of Bolgona, when various cultural spaces open their doors until midnight. Here, an extraordinary show documents the rich artistic movements of revolutionary-era Russia, Revolutija: From Chagall to Malevich, from Repin to Kandinsky (12 December 2017–13 May 2018).

Curated by Evgenia Petrova, Revolutija features some 70 works, including a beautiful suprematist composition by Olga Rozanova, Non-Objective Composition (c. 1916), and two paintings by Ilya Repin: one of the 17 October 1905 revolution painted circa 1907, and the other depicting a couple surrounded by crashing waves (What an expanse! 1903). Early and later canvases by Kazimir Malevich are also on view, including a red square from 1915, Red Square (Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions); while a suite of impressive canvases by Pavel Filonov included a trippy, hyper-cubist painting from 1916 depicting, as understood by the work's title, the Flowers of the Universal Flowering. (Another great painting—in a show filled with them—was Ilya Maskov's camp portrait of himself with Pyotr Konchalovsky from 1910, showing both men sat side by side in their briefs, one holding a violin and the other somesheet music.)

Carrying on with the revolutionary theme was La Mostra Sospesa, an exhibition at Palazzo Fava, covering the work of the Mexican Muralists José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros (19 October 2017–18 February 2018). (Though Orozco is said to have been critical of the Mexican revolution.) With 68 paintings on view from the Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, the Museo Nacional de Arte, and the Museo de Veracruz, the exhibition staged a show that was meant to open in Santiago, Chile, on 13 September 1973, only to be cancelled after Pinochet led a military coup on the 11th of that month. (The works intended for the show left Chile on the same plane ferrying the widow and daughters of the ousted president Allende, who killed himself that day, to exile.)

With such a red thread running through these two world-class exhibitions, it seems Bologna has retained a sense of its revolutionary past, despite the changes currently sweeping across Italy and Europe, with some local commentators noting, in conversation, a shift in politics in the city towards the right. Reflecting this complex fabric was Bologna's historic fair, which naturally pulled the city's extensive history into its remit. —[O]