Making Waves: Sharjah Biennial 13 in Beirut

YOUNG-HAE CHANG HEAVY INDUSTRIES, THE ART OF SLEEP (BEIRUT VERSION) (2006–2017). Installation view: Fruit of Sleep, Sursock Museum, Beirut (14 October–31 December 2017). Courtesy Ashkal Alwan. Photo: Marco Pinarelli.

Sharjah Biennial 13 (SB13), Tamawuj, is a constellation of events, objects and people that stretches far beyond the realm of Sharjah itself. Curated by Christine Tohmé, it was launched in January 2017 with an off-site project at Dakar's Cheikh Anta Diop University, where artist Kader Attia organised a series of workshops, symposiums and performances centred on the theme of water.

Then in March, Act I of the central exhibition, which Tohmé assembled, opened in Sharjah (10 March–12 June 2017) concurrent to the Sharjah Art Foundation's March Meeting. This was followed by Zeynep Öz's curated programme of commissioned works and performances in Istanbul, based on the keyword 'crops' (BAHAR, or SPRING, 13 May–10 June 2017), and a project in Ramallah organised by Lara Khaldi around the topic of earth (Shifting Ground, 10–14 August 2017).

The final chapter of this expansive endeavour kicked off this past October in Beirut with the launch of an off-site project (a two-day symposium around the theme of food, Upon A Shifting Plate, 14–15 October 2017) and Act II of the central exhibition, consisting of two shows. Fruit of Sleep, curated by Reem Fadda at the Sursock Museum (14 October–31 December 2017), and An unpredictable expression of human potential, curated by Hicham Khalidi (with associate curator Natasha Hoare), at Beirut Art Center, or BAC (14 October 2017–19 January 2018).

Framed by BAC's post-industrial galleries, An unpredictable expression of human potential is a grounded and material affair featuring some 18 artists. It opens with Boundary Boys I & II, (aka Border Sphinxes, 2016) by Jesse Darling—guardian lions made from blue masks taped to polystyrene busts with hoodies for bodies perching on plinths. Behind these guardians is Sabrina Belouaar's Malaxe (2013), a video showing hands handling a clump of henna until the white surface over which the action is filmed turns a muddy brown, which is screened on a TV monitor on the floor positioned to face Belouaar's large monochrome canvas made of (and named after) Henna (2017).

In the same room, Dala Nasser's stunning liquid latex skins coloured and augmented by such things as turmeric, charcoal, salt and brick pigment (Yellow Complex, 2015, and David Adjaye's Trash, 2015) hang on a wall. Next to these, a 2016 series of black and white photographs by CJ Clarke, depicting life in the post-industrial English town Basildon (titled 'Magic Party Place'), are on display.

Clarke's images reflect a collaboration with Christopher Ian Smith, whose 2017 documentary New Town Utopia, explores the rise and fall of Basildon: once a hotbed of creativity—Depeche Mode formed there in 1980—since dubbed Britain's worst town. (New Town Utopia is on view in BAC's screening room among other films, such as Eric Baudelaire's Also Known As Jihadi, 2017 and Eric Van Hove's Mahjouba, 2016.)

Expanding on such urban investigations is Randa Maroufi's Le Park (2015), presented in a black-box installation, which follows young people hanging out in an abandoned amusement park in Casablanca.

Through these documentary images (both still and moving) and the material abstractions presented among them, a temporal and contextual link between 'here' and 'elsewhere' is created in this exhibition. BAC is located in an industrial zone near to the Beirut River—a site of active private development. Luxury tower constructions loom over the industrial complex where BAC is housed, next door to the two arts spaces Ashkal Alwan, which hosted Upon and Shifting Plate, and Station, where a number of performances were staged (including Christodoulos Panayiotou's achingly beautiful lecture-performance, Dying on Stage, 2015).

The notion of new town development, in this regard, is abstracted so that the resonances from one context to the next, not to mention the material responses that reflect on them, become at once particular and common, grounded and formal.

This connection between reality and form is expanded in Si Di Kubi (2017), a Tamawuj commission shown in another BAC gallery. Representing a collaborative platform initiated by artists Mohamed Bourouissa and Ghida Bahsoun, musicians Sina Araghi and Sharif Sehnaoui, photographer Dorine Potel, and architect Tony Chakar, the project creates musical compilations according to themes of language, gentrification and economy. It is represented here by an installation of a rough and ready in-house studio, with CDs available for the taking (upon request), and photographs of various market scenes by Bourouissa and Potel on the walls.

The intention, as the group states, is to 'question the neoliberal mechanisms behind music production, and propose a more collaborative and open-sourced approach to shared ownership.' Whatever they produce, the statement continues, is 'distributed back to the informal circuits of production and exchange.'

Collaboration, networking and redistribution are also themes at the stunning early-20th-century mansion that is now Sursock Museum, where Reem Fadda has curated a show that uses sleep as a way to think about bodily processes—from dormancy and digestion to entropy and regeneration—and how these relate to artistic strategies. Citing Haytham El-Wardany's The Book of Sleep, in which sleep is considered a necessity for attaining 'a true awakening' (that is, to dream unencumbered by reality's bonds), the exhibition presents works by 17 artists and collectives.

These include SUPERFLEX's Hospital Equipment (2014), a C-print of an operating table and surgical equipment in a clinical room that represents the actual equipment that collectors bought for Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza after Israel's military campaign that year. (In return, each collector received a copy of the print on view here.) Just recently, a new Hospital Equipment edition has been shipped to Salamieh Hospital in Syria.

Elsewhere, the collective Sigil presents a work commissioned especially for the exhibition. It commemorates a windmill that Sigil built with Yaseen Al-Bushy and Abu Ali al-Kalamouni in Arbin, a Damascus suburb, which used to power an underground field hospital. (The windmill was destroyed by an air raid in June 2017.) __

Electric Resistance—Monument to a Destroyed Windmill (2017), consists of 24 glass vessels with copper and aluminium plates linking each cell into a circle that powers a small bulb. Each vessel represents the 24 months the windmill was in operation, with the plates inscribed with the pages of a book that documents the life and death of the construction.

Works like these reflect on how art has responded to real-world problems through the facilitation of collective action, or by encouraging modes of connectivity. In the case of Tushar Joag's installation Are You Awake (2013), the artist enlisted some 100 people to relay their thoughts on sleep, sleeplessness and waking, documenting their responses with telephone scripts and sound recordings collected over the course of one day. In one of Joag's transcripts, one person asks the obvious question that Fruit of Sleep seems to pose without asking outright: 'How can we sleep peacefully with all this happening?'

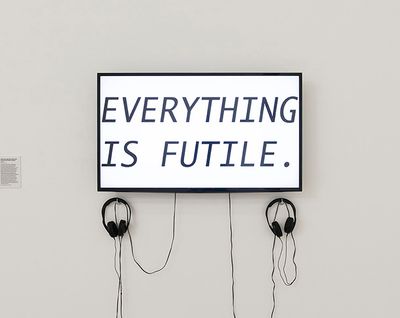

While in reference to post-Independence India, the query applies to the art world, too—something YOUNG-HAE CHANG HEAVY INDUSTRIES touches on in THE ART OF SLEEP (BEIRUT VERSION) (2006–2017). In this video, the words of an 'insomniac narrator' ruminating on the art world flash on screen to a swinging jazz soundtrack. The tone is delirious; 'THE LAST THING THEY WANT US TO KNOW IS THAT THEY'RE CLUTCHING FOOL'S GOLD', reads one sentence; 'EVERYTHING IS FUTILE', says another.

At one point, the idea that anything could be art is posited as enough to put someone (in this case, André Breton) out of a job—a point that speaks to the fact that, while often aligning itself with collective and emancipatory politics, art often upholds the very systems it critiques because survival demands it.

It is at this junction between complicity and reaction that Fruit of Sleep makes its point. In Mujawara / The Tree School (2014–ongoing), a circle of stools are arranged around a tree that hangs overhead, with a children's storybook, The Tree School, made by Campus in Camps in collaboration with Contrafilé, placed on each. In one story, a few lines seem to express how the idea of sleep in this show, as a site of boundless possibility, has been interpreted: 'Silence is a special kind of action, and it's always at our service. It's a way of being, of moving from place to place.'

The idea of silence as a tactic through which to cut through the grandiose noise of the art world's oft-vacuous political gestures returns to An unpredictable expression of human potential at BAC. As Khalidi and Hoare explain in that exhibition's curatorial essay, the idea was not to ask for solutions from its artists, nor to sketch out utopias, but rather respond 'to the present global moment ... in which a paradigmatic shift can be tasted in the air'. Perhaps there are no words to describe the present; or maybe they have become inadequate when it comes to its mounting problems, including an ecological crisis that can no longer be ignored.

But words are needed to create necessary ruptures. This was the case with one talk that stood out during the programme of lectures, discussions and performances that constituted the off-site project Upon a Shifting Plate, organised by Tohmé at Ashkal Alwan, which included Candice Lin's lunch-time performance Destroyed Documents and James T. Hong's illuminating evaluation of Nietzsche's philosophy through the gut's microbiome.

Lina Mounzer's 'Hunger and Hallucination: Tales from the Great Famine' detailed Lebanon's devastating famine during World War I, and mentioned the profiteering Michel Sursock undertook by hoarding wheat supplies and engaging in price speculation. This wove a damning frame around the pristine white cube in which Fruit of Sleep was staged, bringing to attention the contradictory context of the Sursock Museum itself, next to which the towering Ibrahim Sursock Residences loom: 'a landmark project' that smacks of the private development that has shaped so much of Beirut's postwar landscape, while pointing to art's relationship to such processes.

In fact, when it comes to the Beirut chapter of Tamawuj, all roads led to the Sursock Museum, and in particular, the museum's esplanade, on which Radouan Mriziga's performance 55 (2014) saw Mriziga create a design based on Islamic geometry with his body as both compass and protractor, marking out points and circles with chalk on the ground that were connected with neat lines of masking tape.

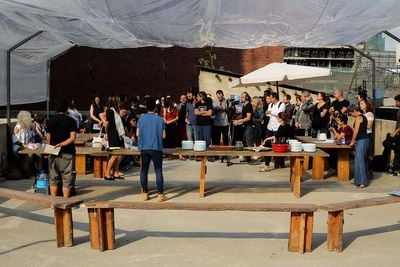

The symbolism of Mriziga's performance felt like a clue. It was on this esplanade, after all, that the dots Tamawuj laid out connected—at least, this is what it felt like during Franziska Pierwoss and Sandra Teitge's performative dinner, 'A Tale of Trash Mountains, Garbage Rivers, and Migratory Birds', which was staged there. Tables of eight people each included at least one specialist in waste disposal who was positioned to steer discussions surrounding a hot topic: waste management. In 2015, a garbage crisis erupted when the Naameh landfill—the sole site to deal with Beirut and Mount Lebanon's rubbish since 1997—closed with the government offering no replacement. These events prompted the 'You Stink!' protests and spawned the Beirut Madinati movement.

At various points during the meal, different speakers were invited to stand up and share their knowledge or experience of waste management. Notably, one representative of the Beirut municipality—an advocate of waste-to-energy (essentially the incineration of garbage as if it were coal)—spoke early on. What followed was one speech after another from academics and specialists; many of them critics of the waste-to-energy approach, who listed reasons against such a path. (Namely, the effects this has on the environment and on human health.)

As the night wore on, and after the municipality rep stood up again to respond to the critique (only to sit down, hunch over and light a cigarette immediately afterwards), it became clear that this gala dinner was a ruse. An art-performance became the platform upon which ideas and positions were networked and presented to a municipal figure who was honey-trapped into attending.

It was here that the themes of nature and networks—organic, technological, and political—joined with conversations that have taken place throughout Tamawuj's run, which have examined how art's agents and institutions might effectively respond to the politics of the times. It was here, too, that the logic Tohmé applied to her curatorial by redistributing the resources of the Sharjah Biennial across different cities and spaces became visible in an active response to a contextualised political issue.

This instrumentalisation of an instrumentalising space—that is, the contradictory space of art and its institutions—is by no means an insignificant feat, no matter how small the gesture might seem. It offers an example of how the means of curatorial and artistic production might enable actions with real-world effects. Even if those effects manifest in a fleeting moment in which state or institutional power—at least, a tiny fraction of it—is compelled to listen.—[O]