Tentacular Thinking through the Unfaithful Octopus

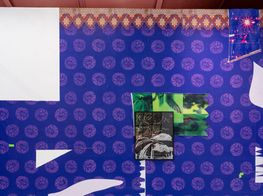

Left to right: Diem Phung Thi remade by Thao Nguyen Phan, Seating (c. 1970s; remade 2023); Chulayarnnon Siriphol, Forget Me Not (2018). Exhibition view: The Unfaithful Octopus: Image-Thinking and Adaptation, ADM Gallery, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (12 October–1 December 2023). Courtesy ADM Gallery.

The octopus' alien ingenuity and tentacular reach are judicious metaphors for a refusal to commit to a single discipline or linear chronology.

For The Unfaithful Octopus: Image-Thinking and Adaptation at ADM Gallery in Singapore, curator Roger Nelson borrows the conceptual device of the octopus from theorist Mieke Bal to shore up his own essayistic exhibition-making approach, one that is experimental, playful, and partial. According to Bal, the octopus' main body is a contemporary vantage point from which its cunning limbs can grasp and draw in an array of sources, timelines, and contexts.

Nelson also prominently references the art and writing of Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook in his curatorial text and process. With these interpolations, he underscores the work of eight artists and collectives, including Bal and Rasdjarmrearnsook, most of whom are from or based in Southeast Asia. Installed across two spaces are videos, installations, and mixed-media works that cite, build upon, or deviate from artistic and cultural references from other times and places.

Bal's essay-film, It's About Time! Reflections of Urgency (2020), is itself an amalgamation of quotes from books and paintings. In one scene, an actor restages a 17th-century Caravaggio portrait of John the Baptist, awkwardly mimicking John's pose alongside a cheap reproduction of the painting. By ventriloquizing art history, Bal's film actively reimagines it.

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook also referenced artists such as Jeff Koons, Artemesia Gentileschi, and Édouard Manet in her video works of the late 2000s and 2010s, where she staged encounters between Thai villagers and replicas of canonical artworks. While these are not shown at ADM Gallery, presented is Rasdjarmrearnsook's video Reading Inaow for Female Corpse (Lament Series) (1997), in which the artist communes with corpses, putting an arcane twist on her address of an audience's relationship with art. Seated on a chair facing a covered cadaver, the artist wistfully sings verses from the Inaow, a centuries-old Thai epic poem about love and desire that is adapted from Javanese legend.

Communication is equally and beautifully opaque in Rasdjarmrearnsook's 2022.3 and 2022.4 (2022), a pair of abstracted digital prints depicting monochromatic cloudlike puffs and pink-purple petals which the artist has further embroidered with pearly-hued petals. To create the inky black-and-white grounds, Rasdjarmrearnsook reconfigured digital news images of the ongoing devastation in Ukraine, but she circumvents a sensationalist bent by omitting any images of people or destruction. The work's hauntingly elegant washes and textures, like Rasdjarmrearnsook's intimate whispers to her coterie of corpses, give little else away.

Rasdjarmrearnsook's sensitivity to art and life is rare, evidenced in the subtlety of her appropriative technique and conceptual apparatus. Other artists in The Unfaithful Octopus tend more towards Bal's theoretical resolution with their lineage of citations. The 90-minute film Forget Me Not (2018) by Chulayarnnon Siriphol sees the artist play both male and female protagonists in a satirical reenactment of Siburapha's 1938 novel Behind the Painting, a love story between a commoner and an aristocratic woman.

More understated are Thao Nguyen Phan's reproductions of curvilinear chairs by modernist sculptor Diem Phung Thi, which were originally designed for a public library in France in the 1980s. Thi derived the chair forms from her own modular sculptures. Phan's (and Thi's) sturdy chairs are placed strategically throughout the space, providing seating for audiences to rest and watch other artists' films and videos.

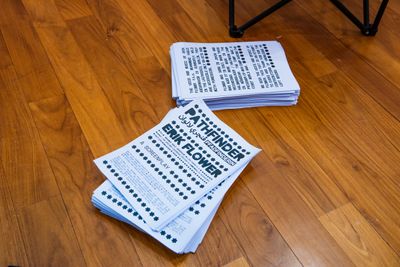

Fyerool Darma takes greater liberties with his reinterpretations. With characteristic obscurity, Darma layers an esoteric assortment of cultural references, found objects, sound, text, and AI in his installation Pathfinder (2023). Here, Darma tries to revive the enigmatic 20th-century cultural figure Erik Flower.

Little is known about Flower; he was born Muhamad bin Hadji Abdurahman in Johor, in what was then known as the Unfederated Malay States. Flower relocated to Berlin in 1917 (Darma suspects that he was a prisoner-of-war), where some recordings of his music and poetry are stored in a sound archive.

Despite his unsuccessful request to access these materials, through his installation Darma fabricated a rich life for Flower from what little information he could gather. Components include a 2021 essay by meLê yamomo which briefly mentions Flower, and an original screenplay (written by Johor native Sharmini Aphrodite, with an accompanying soundtrack produced by musicians berukera and gr834$ternl4if). An AI-generated portrait of Flower could be mistaken for a poster promoting his latest album: a grey flower is emblazoned across the left side of his face, with his name and the work's collective title surrounding in bold capitals.

Even as he attempts to remedy Flower's historical absence, Darma ironically rejects identification as Flower's glorified 'pathfinder' with his typically circuitous and collaborative mode of working. In a similar way, what is perhaps most alluring about the octopus is not its acquisitive ability or the impressive span of its limbs, but its indecipherable curiosities. It is this intrigue that the most captivating artworks in this exhibition grapple with. —[O]