Tracey Moffatt

Natalie King with Tracey Moffatt at the artist's studio. Photo: Maja Baska.

Natalie King with Tracey Moffatt at the artist's studio. Photo: Maja Baska.

Since graduating from Queensland College of Art in 1982 and following her first solo exhibition at the Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney, in 1989, Tracey Moffatt has become one of Australia's most renowned contemporary artists.

She first gained significant critical acclaim when her short experimental film Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy (1990) was selected for official competition at the 1990 Cannes Film Festival. Shot entirely in the studio with lurid colours and sets, Night Cries explores the relationship between an Aboriginal daughter and her adoptive white mother. Subsequently, beDevil (1993), Moffatt's first feature film comprising three supernatural ghost stories featuring a central character haunted by ghostly apparitions, was also selected for Cannes in 1993. In 1997, she was invited to exhibit in the Aperto section of the Venice Biennale, curated by Germano Celant, and a major exhibition, Free-Falling, was later held at the Dia Center for the Arts in New York (9 October 1997–14 June 1998). She has been included in the biennials of Gwangju, Prague, Sao Paulo, Sharjah, Singapore and Sydney.

For the 57th Venice Biennale, Tracey has assembled two new photographic series—'Passage' and 'Body Remembers'—and two filmic videos—Vigil and The White Ghosts Sailed In—under the overarching rubric My Horizon. In all of these works, the poetic and personal meld as we are invited to look out and beyond, towards the unobtainable: what might be over the horizon. In the case of Spirit House from the 'Body Remembers' series, Moffatt depicts an abandoned, crumbling ruin with the central protagonist, Moffatt herself, taking refuge within shadowy portals.

Throughout 2016, I visited Tracey's cottage studio in Sydney's Middle Head observing her new work unfurl with many detours and experimental forays. As her curator for the Australian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, I became comrade, confidante and accomplice. We conducted three in-depth interviews that reveal insights into her tenacity, fearless focus and plethora of influences. She is immeasurably creative, unstintingly passionate and a consummate storyteller. Her epic, new photo fictions for the Venice Biennale draw on a multitude of references from the first film she saw at age five, Mary Poppins to Elizabeth Bishop's poem Insomnia (1955), which is an exhortation on love. This limitless array of sources can be traced back to Tracey's fascination with the work of Surrealist filmmaker Maya Deren, whom she studied at art school in Brisbane.

Tracey's stories are open-ended narratives, partly fictional from her imagination and partly based on her own family history. She takes her camera into unknown locations to create photodramas with models, actors and people found on the street. Her carefully constructed scenarios and vignettes are intensely theatrical and resonate with references to film, art and the epic history of photography. In her fraught narratives, characters are consigned to shadows and dreamy scenes within a dislocated world of exile and crisis. In so doing, Moffatt takes the tempo of our times.

Today, Tracey continues to exhibit extensively in the international arena, including in 2016 at the Centre Pompidou (Paris), Artspace (Sydney), Seoul International New Media Festival and The Kitchen (New York). For the 57th Venice Biennale in 2017, she has been working from an old cottage in Sydney bushland. From here, she has been able to conjure images and ideas. But ultimately, she can make art anywhere.

The following is an edited extract of our interview, which appears in full in Tracey Moffatt: My Horizon, edited by Natalie King and published by the Australia Council for the Arts in association with Thames & Hudson, 2017.

NKThe title of your exhibition for the Australian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, My Horizon, has been described as a 'line where the sky kisses the sea'. How is the poetic and personal a feature of the new work you created for the show?

TMMy Horizon can be about one wanting to see beyond where one is. It can mean to have vision. It can mean to project out and exist in the realm of one's imagination. This is what artists do, this is what I do, and it is what saves me. Or one can accept the title in a more literal way in the reading of all of my artworks in my Venice Biennale exhibition. The image of the horizon line is featured in most of my images; in my two photo-drama series, 'Passage' and 'Body Remembers', my fictional characters are seen to gaze off out to the horizon line. My characters possibly dream of escape, or they are weighed down by their own memories or histories. The same can be said of my two video pieces, The White Ghosts Sailed in and Vigil.

My Horizon can describe reaching one's limitations or wanting to go beyond one's limitations. It can be likened to a dream state, like when one looks out and beyond where one is. The horizon line can represent the far and distant future or the unobtainable. There are times in life when we all can see what is 'coming over the horizon', and this is when we make a move or we do nothing and just wait for whatever it is to arrive.

NKWhat is the role of fiction and make-believe in your staged photo fictions?

TMI have always been enthralled by make-believe and the 'set-up'. I have never been very interested in capturing reality with a camera, but rather creating my own version of reality. I can use fiction to comment on my own personal history or serious issues of social history or reflect on what is going on in the current political landscape.

NKYou are renowned for experimenting with the medium of photography, inventively manipulating form so that photography enters other realms. Could you elaborate on the influence of early vintage photography such as daguerreotype, glass plates or magic lantern image projection in the 'Body Remembers' series? You have enlarged these old-fashioned-looking toned photos to small billboard size.

TMI am always looking at my photo history books and hardly anything inspires me more than a grainy vintage black-and-white photograph. I stare with fascination at reproductions of the first recorded photograph ever made with a camera in 1826 by Niépce, who shot a view of Paris rooftops, I believe. I read that the picture was made using bitumen of Judea, which sounds biblical to me, and it even comes from the Middle East and has also been called Syrian asphalt. I want to make a photograph using this ancient process but it sounds complicated, and it is probably dangerous to inhale.

Bitumen is that black tar substance that you would squish underfoot on a new-built road. As a child, when I would run errands barefoot, it was gooey and jet-black and it would stick to me, burning my feet. It was the colour and texture of the liquorice-stick candies that I was dying to buy and still want to eat. I always wonder now if I could scrape up the hot bitumen, I could form a photo like Niépce: crude yet ethereal, with the image barely there. One of the dreamy qualities that I like in an old photo is the indistinct. What one can't see beyond the grain and blur. Often in my own photos I strain to obtain the 'indistinct', but because I work with narrative I must work towards a visual clarity.

I print a photo and show it to a friend or my art dealer, and if they can't understand or 'read' any narrative at all then I think that I have failed. I must correct the image; it is exactly like editing a movie. A movie producer can hover over the director as they edit a movie and say: 'But I don't understand why the guy is walking into the burning building. What is his motive? You didn't set up the reason beforehand. I don't understand this guy, therefore I'm going to walk out of the cinema.'

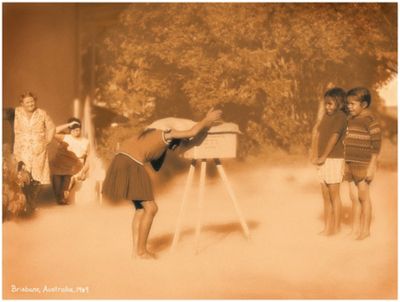

I look always at vintage photography because I am looking for a purity of intention, a type of naivety. I look for a moment that was not intended. I collect early tourist brochures of country towns showing 'scenic views' with text descriptions, as well as early government pamphlets showing the food production industry. Recently I found some from the twenties of the Blue Mountains just outside Sydney. I stare at the paper stock and simplicity of layout and design, how the early offset printing ink fades or bleeds from the photo images. With my ten-image 'Body Remembers' photo series I wanted to create an oversized, overripe sepia-toned memory bank. I hope the large photographs fall somewhere between Surrealism in the tradition of a Giorgio de Chirico painting, with his shadows of the afternoon, and the black-and-white illustrations of Napoleon in Egypt in 1799.

NKYou have a personal family history of 'service'; your first job at 15 was as a live-in nanny for a family on the Gold Coast in Queensland over summer. Your mother, Daphne Moffatt, worked as a domestic for a doctor in Brisbane in the 1950s, and your grandmother Maggie Moffatt was a cook and domestic on a mountainous cattle property called Mount Moffatt Station in Central Queensland around 1910. Could you talk about how you cast yourself into 'Body Remembers' as a female maid mourning the passing of time, lingering with longing in an arid ruin?

TMMy 'Body Remembers' series has been a personal journey, and I play the role of a maid in this work. The maid with upswept hair is dressed as if from the fifties, and she returns to the ruin of the house where she once worked: a place of memory and of where she felt a sense of security and perhaps a lost love. We see the interior of the house as it once was and again as in ruin. The dream-like distilled images have titles such as Touch and Worship, and I hope they might be viewed as if in an unnamed country, not only Australia but possibly North Africa, Mexico, South America, the Middle East and even Italy. Any country with small stone hamlet ruins that dot a desolate landscape. The ruins become a type of rock altar or like a large abandoned headstone at a gravesite.

My 'Body Remembers' images are suspended in a nowhere space and time. We don't know if my maid character projects her life into the future, where the house she works in has become a ruin. Or is it that my maid character returns to the ruin to relive a strong memory, perhaps of someone she knew in the house? We see her perhaps remembering someone and their presence in the third image entitled Touch.

I photographed this 'Body Remembers' series in a remote region, and I created a fiction around the locale. I may in part be paying tribute to my own mother Daphne and my maternal grandmother Maggie Moffatt, whom sadly I don't know a lot about. Some years ago, while I was creating Spirit Landscapes (2013), I wanted to visit the cattle property where my grandmother lived and worked. I wanted to walk where she walked and stand in the ruin of the kitchen where she once cooked. The Mount Moffatt cattle station ruin is almost unreachable, but perhaps someday I will make it there.

I have often worked like this in creating my photo dramas. I find the location first, then I start to spin a story. The location inspires the stories and then the characters emerge. Then, after that, the 'look' of the artworks starts to appear.

NKCould you discuss the desolate house and ruin in 'Body Remembers', with the central, female protagonist (you) standing in apertures, at a window, in a doorway, by a bed or before a hearth?

TMAll ruins have intrigued humans forever, and the image of the ruin appears throughout the history of painting. Ruins can trigger nostalgia about past grandeur or, if it is humble such as a farmhouse, it can move one to think of a simpler rural, happier existence. A ruin can take us out and away from our present-day troubles. Therefore one is attracted to ruins, and teenagers are known to break into abandoned houses and desecrate them even more.

In 'Body Remembers', the maid played by myself appears to be revisiting a house where she once 'served'. Memories flood her. The images switch back and forth between the past and present, and nothing is visually explained. The images operate in the realm of Surrealism, where nothing appears to be what it really is. I quote here the last paragraph of 'Insomnia' by American poet Elizabeth Bishop:

. . . into that world inverted where left is always right,

where the shadows are really the body,

where we stay awake all night,

where the heavens are shallow as the sea is now deep,

and you love me.

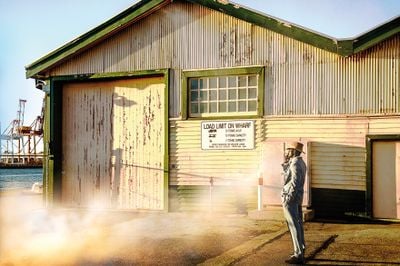

NKThe series of photographs in 'Passage', rendered in saturated colour, is set in a fictional location that could be a mysterious port on the edge of the Indian Ocean or North Africa or the west coast of Australia, searing with the prospect of danger and escape. Could you discuss how this locale invokes places of transit, hidden journeys and illegal passages?

TMMy photo series 'Passage' has the look of film noir forties Hollywood movies but in colour. The setting is a grim docklands, a 'waterfront' that could almost be in any country. I have tried not to 'locate' the story so that it can hopefully 'move' and be 'read' by many cultures. It isn't that I feel limited by always having to comment on Australia, the country where I am from and where I now live; it is that I have always wanted my artworks to 'cross borders', so that my photo scenarios can be instantly recognisable to anyone. In the 12 images from 'Passage' I have a small cast of characters, some of whom look African though they could also be American. The setting could be Brooklyn in New York or New Orleans or more exotic, and most of all I would love it to be read as some colonial African outpost port—it could be Nairobi or Entebbe. I love city names that seem to sweep you up into a story as you are saying them. The best one would have to be Kinshasa in the Congo: Kinshasa sounds like a drumbeat as you are saying it.

I want the forties era to read as 'of the past', but the storyline speaks about what is happening in the world today with asylum seekers illegally crossing borders. But I don't want the images to read as a dated news story, because in fact the asylum-seeking storyline is not a new story but it is one as old as time. People throughout history and across cultures have always escaped and crossed borders to seek new lives. You and I, Natalie, for sure, have had relatives from our past who would have had to 'jump ship' to go ashore into 'new lands' or climbed on board ships illegally as stowaways. I have always loved artist Willem de Kooning's story of how he was an illegal stowaway on a ship, arriving in the US in 1926. He hid below deck and then managed to get himself into New York; here is someone who reinvented himself. He went from sign painter to genius Abstract Expressionist. I find reinvention so thrilling because it takes guts. Though with asylum-seeking now, as we all know, such journeys are done out of desperation. The recent illegal sea voyages are full of danger.

The storyline I have invented for 'Passage' involves a young woman dressed for stowaway travel and a baby boy who isn't, a prowling motorcycle cop and a sharp-suited 'middleman' dude who smokes a lot. They all meet in dark streets and laneways by the harbour and all are tortured individuals. I have never liked to finalise my scenarios but rather leave them open to interpretation. The inferno of emotions visible in my images has to do with the baby boy, who is either sold to seek illegal passage or he is rescued from being sold. In the opening photo, entitled Mother and Baby, the young woman nurses him and she is showing him the horizon line, which could represent his brand-new future with or without her. We see the mother in a swirl of yellow fog gripping her baby boy. She is saying goodbye to her baby, but he is squirming away from her. She could be reunited with him, or she could be about to give him away as he is fading into the yellow murk of fog. The baby's face is turned away; he looks outward towards his different future. His mother will fade from his memory, as is the case in such real-life situations. His mother's face is already unreadable and hidden in a cloud; he will not remember her face, but he might remember the feel of her. When I photographed this image I set a fog machine to create an ambience. I hoped that the effect would look painterly and soften the harsh real-life look of the digital photo, and that the afternoon light would refract with the fog as it drifted.

When I worked on printing this picture, I tried to make the image of the young woman solid and strong, but she would not come through the fog. In the end, I knew that the mysterious process of photography was not letting me 'have her'. Photography was telling me my 'Passage' story. The young woman might fade away from the baby's life and be nothing but a distant memory to him. I have often felt that when I develop my photo dramas my characters emerge, like in a novel. Fiction writers talk about their characters taking over and speaking to them as they write.

NKYou read and watch films voraciously. What have been the seminal literary and cinematic influences on your new Venice Biennale work?

TMOh dear, where do I begin to pinpoint references? All of my artworks come from almost everything I have ever read or looked at or have experienced in real life. My memory bank is huge. I hope my 'Body Remembers' photographs have the look of a visual poem (and I do love poems, too numerous to mention), but in the end the images are meant to be visual art—they are not words on paper. The 'Body Remembers' images have their own strange colouration. I have worked with ochre hues of reds, browns, yellows, greys, blacks and pulsing whites. I want the images to vibrate as if they are out of the earth and the sun. My 'Passage' photo-drama series is a definite homage to old movies, forties film noir, though in hot colours, not in black and white.

It has taken me more than 12 months to find my 'palette' for all of my new Venice Biennale photo works. My never-ending experimenting and testing at the photo-printing labs has made me insane. The moment I stop printing is when I think I have hit a mark, when I think that I have never seen such an image before. I only stop when I think that the image is finally original. I also stop when the image is 'working' in terms of the narrative I have created. For example, I decide whether I need to open up a shadow or to darken it down. It is about creating a visual mood.

NKVigil, which continues your ongoing montages of filmic riffs, is imbued with scopophilia [a form of voyeurism in which viewers get sexual pleasure from looking], especially a terrorised still of Elizabeth Taylor combined with footage of asylum seekers in perilous boats. How has the plight of refugees informed this new, urgent work?

TMThe television news story about the asylum-seeker boat that crashed on the Christmas Island shoreline back in 2010 is a horror. About 50 people drowned. The boat, carrying mainly Iranian and Iraqi Kurds, disintegrated in rough seas before our eyes. It is a tragedy that has haunted me since, as do many news stories. We can never fathom the desperation of the people who got onto that awful boat and crossed the horizon and tried to make it to some sort of freedom in Australia. The smashing of that rotten wooden boat is symbolic of how borders around the world are disintegrating. The old world is out, the new world is coming in and borders cannot stay closed. Human beings, in their desperation, will always find a way 'in'; they always have.

In Vigil, I juxtapose images of white movie stars gazing out of windows at dark-skinned people arriving on boats. I have created visual graphics based on recent images we have seen in news stories of refugee people in boats. Vigil therefore can also be read as a blatant commentary on 'race'. There is nothing subtle in the editing and construction of Vigil.

NKYou moved back from New York to Sydney after 12 years of living in Manhattan. Could you describe your current studio environment and working rituals? Do dreams inform your visual compendium?

TMI have never had a studio to work in. For the Venice Biennale I was granted the use of a room in an old cottage in Sydney bushland. It has been wonderful to have a separate workspace apart from my small apartment where I usually work. I have no routine to my working day, apart from trying for 30 boring minutes at the gym. When I am supposed to be working on my art I can easily spend two hours in a shopping centre staring into space. I can spend five hours a night watching television. I can lie on my back for eight hours riveted to a book that I can't put down. I might spend days seeing no one and doing nothing but house-cleaning and perhaps chatting on the phone to friends and laughing my head off really loudly. What I describe above can be viewed as wasting time, but it is only that I am 'emptying out'. I empty out all of life's important responsibilities. I am then able to conjure images and ideas, or rather make space for creative thoughts to enter me.

In the end I am an artist who is dead serious about wanting to move forward and experiment with the photographic or film and video form. I still strive for old-fashioned artistry with the camera, and I want to push the photo image into other realms. Still, after 40 years of camera play, I get as excited to see the results of my photo shoots as when as a teen I would dash to the chemist shop after school to pick up my latest photo instamatic creations. It has been a struggle for me to develop this new work for the 2017 Venice Biennale. Art-making is not easy, and it does not appear overnight. It is a system of painstaking process beyond one's control. Artwork images decide when they are ready to emerge; the artist can only funnel them to a type of completion. Art is never, ever 'done'. —[O]