The Garden at chi K11 art space

Shane Aspegren, Weather's always changing, for a limited time (detail) (2017). Water, dehumidifiers, aquarium, Medusomyces gisevii, insect electrocutor, automatic scent dispenser, artificial plants, sound recordings, speakers, cables, media players, other electrical components. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist.

A comparison between the control and study of nature in 'The Garden' and Hong Kong's unique political situation is clear in this exhibition.

Artist and curator Enoch Cheng showed off his green thumb when he organised the multiform group exhibition The Garden (2 September–13 October 2017) in Hong Kong. The show featured works by himself and nine other artists: Neïl Beloufa, Cai Kai, Ian Cheng, Cheuk Wing Nam, Vvzela Kook, Shane Aspegren, Andrew Luk, and Samuel Adam Swope. Emulating an 'art garden', where artworks replaced flora and fauna, the show was held over two floors at chi K11 art space in Clearwater Bay, an outpost situated off the beaten path from Hong Kong's dominant art clusters in Central, Soho and Wong Chuk Hang. The gallery is housed in the common building of Mount Pavilia, a new development of luxury residences marketed as an 'art-infused living experience' for the ultra-affluent. Large-scale sculptures by Kum Chi-Keung, Gao Weigang, Jean-Michel Othoniel and Tatiana Trouvé pepper the development's lawn; beyond, Western-style multi-story townhouses surround a mammoth swimming pool.

The architecture of Mount Pavilia's common building echoes the shape of the Solomon R. Guggenheim in New York—the exhibition space is less of a white cube and more of a white, curving snail with large windows that allow natural light to shine in. From the gallery's upper level, the irregular rooftops of the old neighbourhood beyond Mount Pavilia are visible; the conglomeration of trees, small shops, family homes, and the disorderly charm of the nearby village stand in stark contrast to the planned precision and exclusivity of the complex to which chi art space belongs. 'My first impression of the site was unexpected,' says Cheng. He related the ambience of the space to recent experiences of botanical gardens: 'Whenever I entered a greenhouse, there was a different sensation unfolding in me because of the subtle changes in the temperature, humidity, smell or colour of the built space.' At the gallery, automatic doors open to usher visitors inside, while gusts of air-conditioned wind seep into the humidity outdoors.

This experience of the gallery space and its relationship to its context fed into the concept behind The Garden, which opened with French-Algerian artist Neïl Beloufa's Scaffolding Series (2015). Positioned at the entrance to the lower-level space, this uneven and life-sized fibreglass wall on wheels, implanted with pieces of plastic, appears lumpy as though embedded with tumours. In the gallery, electrical plugs were inserted into one side of sculpture's surface, complicating its reading as an interior or exterior structure and pinpointing the bizarre sensation of being both inside and outside; an oscillation which permeated the rest of the exhibition.

The works all alluded to aspects of lifeforms in the material world, sharing a common scientific thread with regards to nature. The bright, light-filled exhibition space lent itself well to emulating a clinical and lab-like environment, with significant elements required for plant life evident in several works treading the line between order and entropy. Beyond Beloufa's sculpture, microbiotics were found in interdisciplinary Hong Kong artist Cheuk Wing Nam's The World of Microcosm (Series of Necropolis) (2017): little piles of undulating white pebbles resembling the flowing shapes of zen gardens, shown in two parts on both levels of the gallery. Small, crane-like machines dragged strands of tiny, artificial 'microbes' over these rocks. In nature, every gram of soil contains anywhere from 100,000 to 1 million living microbes; these microscopic lifeforms, including bacteria, fungi and algae, are important for plant growth. Inspired by her visits to cemeteries and imagining the microscopic lives that thrive on the bodies of the dead, Cheuk made the unseen—and rather morbid—cyclical process of decomposition visible in compelling physical form.

Hong Kong-based musician and producer Shane Aspegren also played with bacteria and the unseen for his installation Weather's always changing, for a limited time (2017). Aspegren arranged the gallery's industrial-sized dehumidifiers with an insect electrocutor, automatic scent dispenser, artificial plants and speakers, into two clusters on the floors of both levels. An aquarium in the composition on the upper floor was filled with a brown, murky substance labelled Medusomyces gisevii—the Latin name for kombucha. The somewhat repulsive, umber and oyster-like 'mother' that ferments the popular tea was visible through the glass (a sight that might disgust some of the drink's more sensitive drinkers). The small speakers on the ground emitted drum improvisations that Aspegren recorded while listening to water sources: dehumidifiers, irrigation drainage ditches, and mountain springs. Connecting with the artist's continued experimentation with the frequencies of nature, the loud, clamouring sounds aimed to reveal the imagined consciousness of the elements.

Ironically, one of the works in the exhibition that most resembled actual plants was made of the furthest substance from them. Hung on the wall on the lower floor and hanging from the ceiling on the upper were the several objects that make up Andrew Luk's Distilled of Fired Leaves (2017). Toying with the control of a forceful element, Luk collected castaway plastic air-conditioner covers and scorched them with a blowtorch, pushing the material to its furthest he could before disintegration, resulting in 'fired leaves' that hung from the ceiling that resembled wilted, overripe fruits dangling from a branch. Luk says the process of playing with fire (seen also during his recent residency at de Sarthe Gallery in Wong Chuk Hang) was one of 'transforming a man-made object into a grouping of organic forms through an elemental method, thereby relating the cover back to its original usage.' The surfaces of the covers were bubbled, scarred memories of their backward alchemic transformation from 'artificial' to 'natural'.

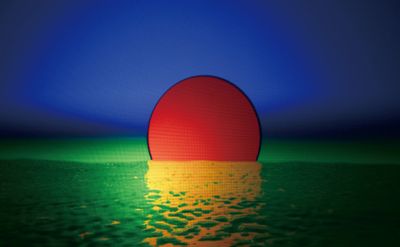

Where nature wasn't presented as bizarre and mysterious, it was shown as reduced and controlled. Samuel Adam Swope's installation Last Breath (2017), on the lower level, was focused on a single green light bulb on the floor, an abstraction of the 'green flash' that occurs at the last moment of a sunset—a phenomenon which occurs for a split second when sunlight is refracted and the atmosphere acts as a prism, separating light into various colours. Upstairs, Cai Kai's digitally-made video Sunrise on the Sea (2014) showed a perpetual, Sisyphean sunrise and sunset over water in RGB colours, while on the lower floor another basic necessity for earthly life—oxygen—was isolated for observation. Swope's Updraft Updraft (2017) is a large, wooden box equipped with windows and a fan, suspended above the floor. Sporadically, the fan at the bottom blows a gust of wind, sending hundreds of paper simulations of maple seeds flying within the box. Known for his 'aerial art' that integrates flight and levitation as a means of visual expression and air or gas as a medium, Swope uses the paper seeds to observe the aerodynamic logic of the airstreams. Akin to the bacteria in Aspegren's aquarium and the mechanical bacteria on Cheuk's pebbles, the seeds were contained within a viewing space in this show, and alluded to an underlying sentiment that became clear throughout the exhibition. When confronted with nature and the unknown, the human compulsion is to arrange it into a set of laws that attempt at understanding and control.

Gardens are luxuries, especially in the compactness of Hong Kong, and are familiar signifiers of leisure and well being. It's no wonder city planners construct a greenspace where public unease is sensed. In 1995, the now-levelled, infamously crime-ridden Kowloon Walled City was replaced by a 31,000 square metre Jiangnan-style garden. Hong Kong Park in Admiralty, built by the colonial government on the site of a former British army barracks, was opened in the anxiety-filled years leading up to the territory's 1997 handover. Yet the romance of unconstrained gardens wilts in public greenspace: citizens are allowed access only at certain hours and while adhering to strictly enforced rules of behaviour and movement.

A comparison between the control and study of nature in The Garden and Hong Kong's unique political situation is clear in this exhibition. As Chinese rule encroaches upon the territory and political and social freedoms such as free speech are felt to be under threat (universities are currently under pressure to revoke localist learning materials following the heated pro-independence, pro-democracy controversy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong earlier this fall), the relative 'wilderness' that Hong Kongers have enjoyed for years is at risk. The same philosophy that applies to the taming of nature applies also to people: plants may become unwelcome obstructions if left to grow freely, and thus must be trimmed. Incidentally, such manicuring appears to be taking place in the context of this exhibition, located as it is in a development that will eventually affect the natural state that inspired this show. —[O]