The Shanghai 21st Century Minsheng Art Museum

Having been largely left to the weeds for the past five years, the former Shanghai World Expo 2010 site is finally being redeveloped. In the forest of scaffolding and cranes, one of the first finished projects is the China Minsheng Banking Corporation’s second art museum, the Shanghai 21st Century Minsheng Art Museum. The M21, as it’s known in the diminutive, opened late last year in what was originally the French Pavilion.

Designed by Jacques Ferrier to cater to high levels of foot traffic, the former expo pavilion has ramps that draw visitors up through the building, not unlike New York’s Guggenheim Museum. Guests exit through a rooftop garden and descend outdoor escalators to return to ground level.

Renovations by architect Zhu Pei began in 2013, but the basic structure remains the same. The museum, which is free to visit, is already making use of the high-flow capacity with an average of 800-1,000 people passing through each day. Inevitably, several works have been damaged by the busloads of children.

The new museum purports to provide a platform for young artists and focus on new media art and installations, an intention largely apparent in M21’s inaugural exhibition, Cosmos. The theme was determined by Dr Ai Min, Chief Director of the Minsheng Art Foundation, Secretary of the bank’s Social Responsibility Management Committee, and the exhibition’s head curator.

In his preface to the show, Ai argues that quantum entanglement implies plural universes, and the exhibition consequently riffs on themes of layered worlds, virtual and real, dimensions vast and microscopic. This line of investigation is evident, for instance, in Com & Com’s Google Earth Map (2008), a virtual voyage ostensibly over the Himalayas, though in fact the digital mountain range was generated artificially.

The largest work in Cosmos, and the first that one encounters on entering, is Ryoji Ikeda’s The Radar (Shanghai) (2014), an IMAX sized-scan of the night sky that maps out nearby stars. Three high-powered projectors are used to cover one wall of a 12m tall room, added by Zhu Pei, diminishing the viewer as contemplation of the universe, and massive new Chinese museums, are wont to do.

Ryoji Ikeda, The Radar (Shanghai), 2014The show transitions from the astronomical to the atmospheric with a wall-mounted print of Berndnaut Smilde’s Nimbus, 2014, one of the clouds she creates from smoke introduced into a room with carefully controlled humidity. The clouds are backlit and quickly photographed before they dissipate. Our lives are not only small but brief, the exhibition muses in its own cloud of THC-laced awe.

Berndnaut Smilde, Nimbus, 2014It’s not all so ponderous though. Zhou Xiaohu’s Detective Project (2011) is a large cylinder of TV sets, five high by ten around, documenting a chain of ten private detectives he hired to pursue each other, suggesting entangled, parallel worlds. It’s a comical work, like those “Spy vs Spy” cartoons, utterly obfuscating any moral basis to their activities, but nevertheless calls to mind the real need to police the police.

This anti-authoritarian streak appears elsewhere in the exhibition, notably in Mediengrupppe Bitnik’s video Delivery for Mr. Assange (2013), in which the artists smuggle a live streaming camera to the co-founder of Wikileaks where he currently resides, at the Ecuadorian embassy in London. In his installation Civil Diplomacy (2011), Liu Xinyi paints national flags on the opposing handles of torsion grips, mocking how crude and reluctant international relations can be.

Liu Xinyi, Civil Diplomacy, 2011Cosmos includes several other large installations, including Haram Fernagu’s scrap metal tanks Les Jouets qui Traînent (2001) and Yan Lei’s Limited Art Project (2014), a conveyor system with car paneling embossed with random snatches of text: “Andy Warhol in Aspen”, “Pimp Daddy: Now I Place My Heart Here”, and “Touching Stone”.

One of the best installations is Aaajiao’s alien Karensansui (枯山), which is named after Japanese rock gardens, a term that literally translates as “dry landscapes”. Karensansui is derived from a computer program that models movement similar to wind through fur, but is created from smooth sponges that look more like heavy plastic spines.

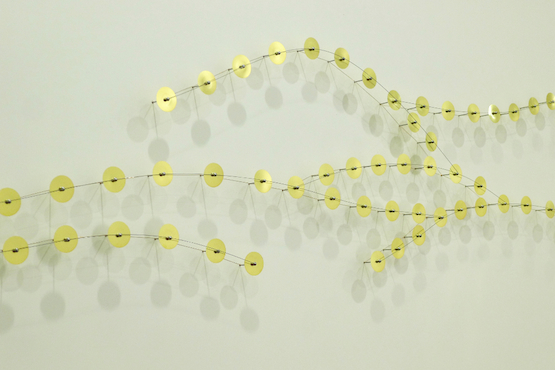

Aaajiao, Karensansui (枯山)Demonstrating an appetite for progressive work, sound and olfactory installations are also included in the show. Alexandre Joly’s Floating Mountain (2014) is a particularly delicate piece, with naked metal discs connected by wire, almost like sakura on thin branches, vibrating imperceptibly to create bell-like sounds. In Sissel Tolaas’s Self Portrait 2014 and Live Forever 01, synthetic replications of the artist’s own smell are trapped in nano-capsules and affixed to the wall. Visitors can touch the wall to release the scent, like a scratch-and-sniff perfume sample in a magazine. Her smell was also infused in the soap in the downstairs bathroom.

Alexandre Joly, Floating Mountain, 2014Some of the strongest works in the exhibition are videos. One room is filled with five large projector screens, arranged at a 45 degree angle to the walls, displaying videos on both sides. The set up is dense, like a library, but fun to browse, and yields discoveries such as David Bestué & Marc Vives’ Actions at Home (2005), actions that include disguising salad ingredients as inedible kitchen items, as if hoarding them against thieves during a period of scarcity.

Perhaps the strongest work in the entire show is Complaints Choir (2005-2013), a video installation by Tellervo Kalleinen and Oliver Kochta-Kalleinen. Projectors are trained on all four walls of a small room. One at a time, choirs in different cities perform their complaints. The Tokyo choir sing lines such as: “Don’t try to get on trains that are already too full”; “I did that job, don’t make it yours”; “I’m scared every three months because I’m a three month contract worker”; “My grandmother thinks she’s American”; and “Pay me the fee you promised, or why’d we make a contract?”. There’s power and catharsis in these moments of malice, performed over a bossanova beat, precisely because they are human, personal and petty—not in the least bit cosmic.

Tellervo Kalleinen and Oliver Kochta-Kalleinen, Complaints Choir, 2005-2013Though the exhibition ends with another interstellar piece—Jennifer Wen Ma’s Forty-Four Sunsets in a Day (2013), a planet-like sphere alive with bonsai trees but drowned in Chinese ink—perhaps a third of the artworks are paintings. There are some excellent specimens, including paintings by Duan Jianyu, Zhu Jinshi and Zeng Lingxiang’s terracotta-like Growth of the Time (2014), but it’s unclear whether these are meant as part of “Cosmos” or part of the permanent collection, with which it’s interspersed. Either way, their prominence calls into question the idea that the museum is really focusing on new media art.

Entanglement is not only a theme of the exhibition itself, but also the exhibition’s entanglement with the permanent collection, the museum’s entanglement of old and new media, and an entangled administration, which sees senior bank staff hold positions that would be better occupied by dedicated art administrators. M21 staff members have expressed little confidence in the museum’s vision.

Jennifer Wen Ma, Forty-Four Sunsets in a Day, 2013M21 has opened in a period of great uncertainty for the China Minsheng Banking Corporation. Minsheng’s president Mao Xiaofeng, 42, who was also the bank’s Communist Party Secretary, resigned on January 30 during a corruption investigation. Major new investors have also cast doubt on Minsheng’s ongoing willingness to fund an art program, with some strange compromises already being made—weddings are hosted in marquees installed in the grounds to raise revenues, the museum will be rented out to Rolls Royce for an entire week this year, and curators have been asked to act as wait staff during banquets. Though there have been assurances that both Minsheng art museums will continue to host new exhibitions, it’s unclear if this is really the case.

Minsheng’s first museum opened in Red Town, an arts hub on West Huaihai Road, in 2010. Under former director Zhou Tiehai, one of China’s best known contemporary painters, the museum arranged impressive solo shows by Chinese contemporary artists such as Zhang Peili and Ding Yi, and historic overviews of Chinese video art and portraiture. One suspects it would take the appointment of someone with similar vision and similarly bulletproof art world credentials to organise an enterprise that for now seems all too terrestrially entangled.—[O]

Open: 10am-6pm, Tuesday to Sunday (last entry 5.30pm)

Entry: Free

Address: 1929 Shiji Dadao, near Tangzijing Lu

Tel: +86 21 6105 2121 - 601

Email: [email protected]