Shifting Waters

Tangled limbs, dark shadows, bark, and skin twist together throughout Shifting Waters, a two-person exhibition at Mumbai's Jhaveri Contemporary featuring photographs by the Ceylonese polymath Lionel Wendt (b. 1900) and a new suite of paintings and works on paper by London-based artist Jake Grewal (b. 1994). But the most beguiling element is light itself, which, for both artists, abstracts everything it hits. It's the common substance—the binding agent—that bridges the century-long continuum of South Asian queer figuration, on either side of which these two artists practice. In their photos and paintings, Wendt and Grewal use the male figure as a template, reduced to the body's gestural outlines, to explore questions of identity, imperial power, and aesthetic inheritance. Their direct juxtaposition puts the painterly effects of Wendt's photographic experiments into relief alongside Grewal's playful absorption of surrealist narrative and tonality.

Lionel Wendt was born on 3 December 1900 into an affluent, mixed-race home: his mother, Amelia de Saram, was a Sinhalese social worker and philanthropist, and his father, Henry Lorenz Wendt, a Supreme Court Justice, was Burgher, of a small Eurasian community of Dutch and Portuguese descendants, longtime settlers on Ceylon, now Sri Lanka. From a young age, Wendt lived a life of cosmopolitan interest, pedigreed by the tony flair of fin-de-siecle Colombo, the capitol city with which Wendt's legacy is now synonymous. In 1919, Wendt departed for London, where he would dispassionately study law at Inner Temple, and with gusto, study piano at the Royal Academy of Music. These were formative years for Wendt, who readily absorbed the tenets of a predominantly white Modernist art and literature. Proust and T.S. Eliot were read and adored; artists like Man Ray and Francis Picabia would later become direct influences on the experiments with photo and film that Wendt would make in the 1930s and 1940s, before a heart attack cut his life short in 1944.

When Wendt returned to Colombo in 1924, he was quick to drop law to pursue a professional career as a concert pianist, and what's more, to further embed himself in the region's social and cultural milieus. With Geoffrey Beling, George Claessen, Aubrey Collette, and George Keyt—all painters—Wendt founded the art collective known as the '43 Group, inaugurating a Sri Lankan aesthetic sensibility built on its own terms. The '43 Group appropriated Western Modernist technique to represent pre-colonial, native, and folk imagery, and this 'both/and' attitude gave Wendt the latitude to use photography to address concerns that experience alone could only fitfully accommodate, including homosexual desire, intoned by the erotic nature of several of the male nudes on display. What's more, this new reproducible medium gave him the aesthetic distance he needed to represent a country and culture that were not totally his own. 'Owing to his in-between position and his use of photography as an apparatus,' notes Kuroda Raiji, the curator of Wendt's 2003 solo exhibition of prints in Fukuoka, Japan, Wendt's images are less legible as ethnographic studies, in that they include an unresolved 'longing for the communities of his country to which he was not allowed to return or belong, and a sense of melancholy that could not fulfill his longing.'

However, before Wendt would turn from the salón piano to the camera and darkroom in the early 1930s, he staked his position as the pioneering artistic citizen of Ceylon. Chilean Pablo Neruda, who held a consulate position in Colombo between 1928 and 1929, wrote that Wendt was 'the central figure of a cultural life torn between the death rattles of the Empire and a human appraisal of the untapped values of Ceylon.' For British documentary filmmaker Basil Wright, Wendt was not only representative of the locale's geopolitics—he became its voice. Song of Ceylon (1934), Wright's four-part, award-winning experimental documentary about Ceylon and its peoples, was made in direct consultation with Wendt, and features voice-over narration from the Ceylon native.

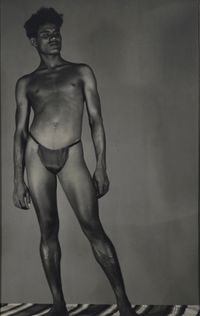

Wendt produced the bulk of his photographs in the last decade of his life, during which he also exhibited widely. By 1936, notes the curator Shanay Jhaveri, Wendt's work had already been displayed in numerous salons internationally and reproduced in various foreign publications. In 1938, The Camera Club in London would exhibit a solo show of Wendt's photographs of landscapes, traditional monuments, studio portraits, and several abstract compositions. Shifting Waters showcases a sliver of the images Wendt produced: studio portraits of young men donning ornaments and holding props (as in Untitled (Man holding a sestha) [1935]) common in Kandyan dance rituals; still-lives composed with pre-colonial masks and richly woven fabric; and a few candid photographs of native labourers and fishermen. Here, Wendt's wizardly approach to the darkroom arts is fully on display: photomontage, solarisation, paper negatives, relief prints, brom etchings, and transparencies—this is only a partial list of Wendt's prodding, madcap engagements with photographic production.

'Someone has seen something,' wrote Wendt, in describing the animus and desire that engenders his work, '[someone has] observed it, been excited by it, made to feel something by it, desired to fix that feeling for himself and communicate it to others—and the result is the photograph.' This desire to 'fix a feeling,' might be read for its biographical import—a la Wendt's queer 'longing'—but it also speaks to his method, which had less to do with the camera than the distortion of the photographic negatives themselves. 'He would spend weeks on the consideration of a photograph,' wrote Bernard G. Thornley after Wendt's death, 'working out every detail on rough paper, before even loading his camera [...Wendt] made a seemingly endless stream of work recording the life around him or the feelings within.'

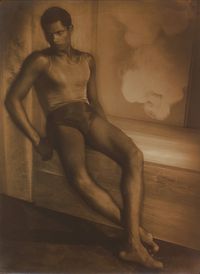

In Mask on cloth (1935), a medieval Sri Lankan mask of a genderless visage— round and unangular, save for the sharp bisection of a nose—is pictured resting against beveled concrete and the draped edge of an embroidered shawl. A third of the composition is shrouded by jet black shadow, while the rest of the image appears manipulated to highlight the dimensionality of each of its discrete elements. Untitled (Head Among Twigs) (1942)—another photograph of a sculptural head, this one placed amid branches—inverts the positive registration of the former image. Championed by the American surrealist Man Ray, solarisation involves exposing a print to light during the development process, reversing the tonal complexion of one or more parts of what's pictured. In other images, Wendt mimics the aesthetics of painting. Untitled (Portrait of Seated Marvan) (1940) depicts a disaffected, muscular youth looking askance, next to what looks to be a partially painted wall or abstract painting. Soft focus and brom etching makes the model's skin powder-like; his outline blurs into the patchy wall he sits against.

The restlessness in the visages of Wendt's images becomes a motivating factor in painter Jake Grewal's massive canvases, which picture (mostly male) humanoid figures against lush, verdant woodscapes. Whereas Wendt illuminates the male figure by way of negative manipulation—over- or underexposing parts of the composition to torque its registration—Grewal's tenderly mottled canvases cast a gossamer sheen across bodies of men and bodies of nature alike. Here, the surrealist's fixed attention to the crisp outlines of the male form becomes a world-building device through which the painter may address queer, South Asian experience in the diaspora as an exercise in aesthetic reflexivity.

Born and raised in south London, Grewal received his Foundation Diploma in Art and Design from Kingston University and a BA in Fine Art and Painting from the University of Brighton. His practice, which spans painting and drawing, uses the conventions of Western landscape painting and figuration as a substrate on which to project unsettling interior landscapes. Dusk // Laid To Rest (2021-22) is one of several double-portraits on display. In it, two ghostly male figures encounter one another in the wood. The scene could depict cruising, though I suspect something far stranger is going on. In the centre of a canvas a swatch of yellow paint destabilises the terrestrial surroundings, suggesting that the pair could be manifestations of the same person, like Narcissus and his aqueous other, or that what is being represented is the process of self-reflection itself. 'Poetry,' wrote the British Romantic poet William Wordsworth, 'takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.' Grewal has admitted to similar motivations: 'natural settings are, for me, an 'access point' for self-reflection.'

The poetic, for Grewal, is a crucial touchstone, where 'poetic' denotes that which verges on sense-making or ineffability. The titles of his paintings tell us this. Whether by way of the comma or his idiosyncratic use of the double-slash '//,' almost all of Grewal's titles include a caesura—a metrical pause or break in a line of verse where one phrase ends and another phrase begins—widening the scope by which his figures might be interpreted: In The Evening, The Sky Changed or Clung Biology // Turned To Heal From Behind. In Clung Biology, two figures stand back-to-back, each with a pose that suggests a devaluation, or possible rejection of masculine form rather than an embrace of it—they could be mid-dance, but one cannot be sure. Like the men and the masks in the photographic prints of Lionel Wendt, the two figures in Grewal's Clung Biology proffer a tension that suggests a body can be as mutable as we let it.

As mutable, perhaps, as landscape is—or, to be more accurate: as 'landscape' is. For landscape, like the nude, the studio portrait and the still-life, is a self- conscious genre. The non-site-specificity of Grewal's paintings an effect of their citational technique. As in Camille Corot's 1858 series of panels Four Times of Day which hangs in London's National Gallery, the figures in Grewal's grottos roam the natural spaces they occupy—they are promiscuous, they pass through. In some cases, they also climb, as humans tend to do: Climber II (2021) shows a waifish youth lift himself up on the low-slung bough of a tree whose leaves, in thick lime impasto, occlude the desirousness in the boy's expression—he climbs without a clear motive. Unlike their painter, Grewal's nudes navigate the benign woods they traverse naïve to the splendour which, in the real world, we continue to raze, deforest, and mine. What does this planetary disappearing act, Grewal's bare-assed nudes ask, tell us about our desires? Despite the Romantic styles these paintings and sketches evoke, the natural world depicted in them is not a conduit through which sublime experience may be eked out for remembrance. Nature, contends Grewal, is instead highly variegated substance against which human agency can only ever be murkily configured. We see what his subjects do not—a world electric.

Press release courtesy Jhaveri Contemporary. Text: Shiv Kotecha.

3rd Floor Devidas Mansion

4 Mereweather road

Apollo Bandar Colaba

Mumbai, 400 001

India

www.jhavericontemporary.com

+91 22 2202 1051

Tuesday – Saturday

11am – 6:30pm