While well known for his later inciteful comic-style paintings and drawings, Canadian American painter, Philip Guston's practice is noted for a determination not to settle in any one established structure, but instead to continually push out the boundaries of painting.

Read MorePhilip Guston was born in Canada in 1913, his parents having fled there to escape the pogroms of Eastern Europe. Shortly after his birth, the family moved to Los Angeles where they were exposed to the violence and racism of the Ku Klux Klan. Four years later—unable to find work in his trade and struggling to make ends meet—his father hanged himself in the family's shed. Guston was the first to find the body. These traumatising experiences, and Guston's subsequent retreat into himself and into the world of comic books, influenced both his initial passion for drawing and the themes he would later revisit in his work.

Guston attended the same high school as Jackson Pollock, and as an adult, Pollock convinced Guston to move to New York. This move brought Guston into the fold of the New York School of painters, with whom he would develop his abstract expressionist language and establish himself as a significant painters and thinker of his generation.

Throughout distinct periods in his career Philip Guston's, style developed and shifted drastically: from figurative muralist, to abstract expressionist, to artist at war between abstraction and representation, and—lastly—to cartoon realist painter.

Guston's formal career as an artist began with social realist murals. He collaborated with others to create politically charged murals, the first of which he completed in Los Angeles with Reuben Kadish. Guston then went to New York in the mid-1930s to work as a mural painter employed by the Works Progress Administration's Federal Arts Project. During his career as a muralist, Guston's influences ranged from Renaissance painters to the American Regionalists and Mexican mural painters.

Between the early- and mid-1940s, Guston began to turn away from murals towards easel painting, experimenting with abstraction. These works were hugely successful and from the 1950s until the 1970s, he became well-known as an abstract expressionist within the New York School—a movement that included artists such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning.

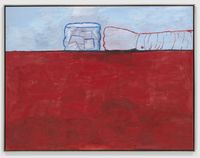

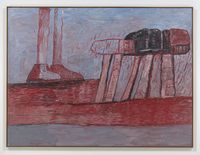

Increasingly dissatisfied with the tenets of abstract expressionism, around 1957 Guston began to push back against his initial success in that genre. He began to believe that abstract art was built around a myth that painting was pure beyond any image. But, as he saw it, painting was in fact 'image-ridden'. The ten-year middle period of Guston's career, from approximately 1957 to 1967, was marked by an oscillation between abstraction and representation, where forms began to emerge but not fully take shape. As Guston's later figurative works became increasingly well-regarded, this middle period became seen by most scholars as merely a stepping stone to his late style. However, in its struggle between creating and obliterating the image, the period holds its own distinct importance in Guston's oeuvre independent of what came before or after.

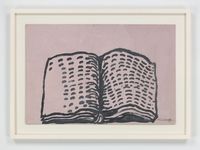

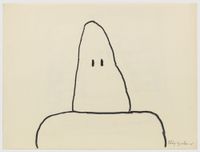

In 1966 and 1967, after his survey at the Jewish Museum in 1966, Guston temporarily abandoned painting and focused on drawing, creating hundreds of works on paper with charcoal and ink. These are known as his 'pure' drawings and emphasise a distillation of thought surrounding structure and abstraction.

Tiring of the New York City art scene, in 1967 Guston moved to Woodstock, New York, where he would begin working on fully figurative paintings of cartoon-like figures in a palette of blues and pinks. The first exhibition of these works took place at Marlborough Gallery, New York, in 1970, where it received scathing reviews from both critics and Guston's former abstract expressionist peers. Motifs repeated throughout this body of work included clocks, light bulbs and Klansmen.

In this new use of figuration, Guston had returned to his roots as a mural painter, reflecting on the sociopolitical unease at that point in the United States' history. Despite the initial negative criticism, he persisted. Towards the end of his life, this comic-strip style began to attract acclaim, and is now his most well-known and influential period, and hugely admired.

Stark in their portrayal and expression of Black pain and racism in America, some of his works have sparked debate and controversy in showing today.

The Guston Foundation Website can be found here and the Guston Foundation Instagram can be found here.

Michael Irwin | Ocula | 2022