David Shrigley Serves 8,000 Tennis Balls in Melbourne

'What I thought I was doing was giving people a nice, clean tennis ball in exchange for a dirty one that their dog might have chewed,' Shrigley said.

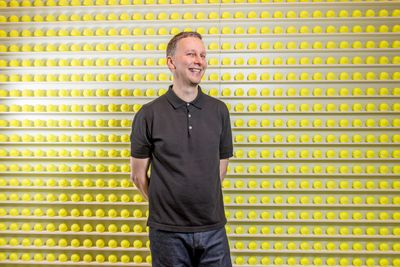

Artist David Shrigley in his Brighton studio. Photo: Mark Cocksedge.

Tennis balls are in hot demand in Melbourne this summer. Alongside the Australian Open, over 8,000 tennis balls are currently installed at the National Gallery of Victoria for David Shrigley's Melbourne Tennis Ball Exchange.

Participants are invited to bring a tennis ball—no matter what state it's in—and swap it for a brand-new one on display.

Shrigley previously staged the Mayfair Tennis Ball Exchange in 2021 at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London. The Melbourne exchange is part of the NGV's Triennial EXTRA programme, which runs from 19 to 28 January.

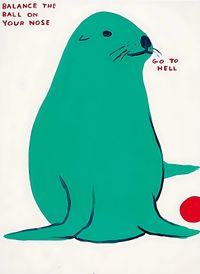

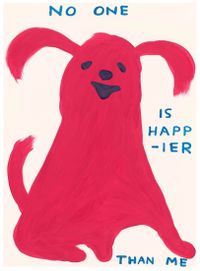

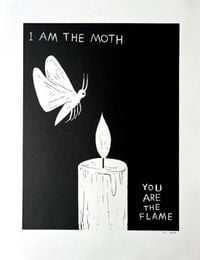

The British artist has noted his surprise at the abstract, Op art quality of seeing so many neon balls on display at once. It's a departure from the idiosyncratic, humorous, and often crude drawings and paintings for which Shrigley is widely recognised, many of which were exhibited in his 2014 survey at the NGV.

In addition to the ten-day tennis ball exchange, Shrigley presents Really Good, a prominent work in the Triennial and hard to miss. The seven-metre-tall bronze thumbs-up monument, originally commissioned for the prestigious Fourth Plinth in London's Trafalgar Square and unveiled post-Brexit in 2016, is positioned smack-bang in the middle of the gallery's water archway entrance.

Shrigley spoke to Ocula Magazine about the Melbourne exchange, and how his passing interest in the racquet sport has led to what is likely the largest display of tennis balls ever to grace an Australasian gallery.

Out of a whole world of objects, why tennis balls?

My dog is really obsessed with tennis balls. But she loses loads, and we have to buy more tennis balls. She drops them in streams and watches them float away. We go up the hill, and she drops them at the top of the hill and watches them roll down the hill and will fight other dogs for the tennis ball, and then just discard it the next moment.

Maybe one would imagine that an artist takes inspiration from something other than their relationship with their pet, which seems very quotidian. Maybe I should be reading Finnegans Wake or something and make an artwork about that, but this is where this artwork came from.

How did the idea for an exchange come about?

I was interested in the idea of exchange, and there's a bit of a dumbarse aspect to it. Now I call it 'Dadaist', because that contextualises it in an art framework and makes it seem like an intelligent, worthy decision. I showed the work initially in a commercial art gallery in London, where normally people buy a bit of my artwork and that means I don't have to have a job, and that's good. But on this occasion, you don't buy anything—you just take a tennis ball and exchange it for another tennis ball.

I've sort of missed the point of what the trade is about in this case, where you're supposed to trade for something that is different to the thing you're exchanging for. What I thought I was doing was giving people a nice, clean tennis ball in exchange for a dirty one that their dog might have chewed. But, in reality, people used it as an opportunity to exhibit an artwork—they made a drawing or wrote a swear word, and presented it like that.

This work is very different from your drawings and sculptures. It's more abstract; more Op, Pop, and participatory. Is this something you are interested to explore further?

I've become interested in the value of art to society and the value of everybody making art. When I was much younger and when I first became a professional artist, I think I was slightly embarrassed about the fact that I had this privilege to make art for a living. Creativity is a really important thing for everybody to engage with. Part of my role as an artist is to encourage people to make art themselves. I've made a number of works that address that, this being one of them, and a couple of pieces that are life models—animated giant sculptures that don't really move.

There's a certain irony that appeals to me in making a sculpture of somebody that's supposed to be standing still. There were all sorts of aspects that were kind of daft and stupid and interesting. But the thing I was really interested in was that it was a catalyst for other people to make art, and the exhibition of the drawings that people had made was the work. That felt really positive, and it started me on a path of thinking about those things, and about the things that I give back to my community. So I'll continue to do that, and I'm quite excited by it.

Any thoughts on the relationship between art and sports, or artists and athletes?

I'm a big soccer fan, to a slightly unhealthy extent. That takes up a lot of my emotional energy. I feel like I don't want to make art about football necessarily because it's my hobby. Although obviously it does seep into what I do—I do have a kind of professional relationship with football as well. I've designed football shirts for football teams and was involved in sponsoring a football team a few years ago in Glasgow.

Are you a tennis fan? Will you catch any games at the Australian Open while you're here?

I only have a passing interest in tennis, the game. I enjoy watching a tennis match, but I tend to only watch it once a year at Wimbledon. Except for this year—I am going to the Australian Open. I'm quite excited about that.

I met Andy Murray, the British tennis player, last summer for some magazine thing. And he's really nice; really interesting guy. His journey through life is a fascinating one. And he's a big hero for all people who aren't necessarily tennis fans, per se. —[O]