Tate Britain Plays Catch Up with Feminist Surveys

With Women in Revolt! and Women Artists in Britain 1520–1920, Tate Britain's upcoming programming features scores of women artists, but do such broad surveys truly do women justice?

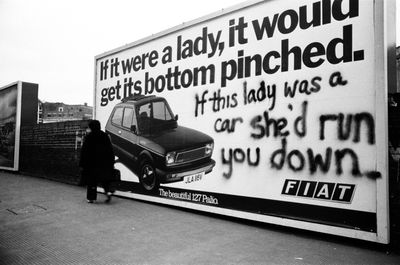

Exhibition view: Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990, Tate Britain, London (8 November 2023–7 April 2024). © Tate. Photo: Larina Fernandes.

Tate Britain's latest blockbuster exhibition, Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990, opens today. Featuring work by over 100 British women artists and collectives, Tate aims to shine a light on the variety of feminist creatives in these tumultuous decades, from the 1970 National Women's Liberation Conference through the Thatcher years.

Women in Revolt!, which continues through April next year, is an acknowledgement that art museums have underrepresented women artists, a point famously made by the Guerrilla Girls, and more recently Katy Hessel, author of The Story of Art Without Men (2022), among others.

The exhibition is part of the museum's larger programme to rectify the gender imbalance. In May of this year, Tate Britain unveiled its ambitious rehang, which included more women in its historical galleries, and ensured that half of living artists displayed would be female.

But one wonders if the sheer volume of artists in Women in Revolt!—which curator Linsey Young calls a 'constellation of voices rather than a few individual stars'—risks saying nothing in trying to say too much.

Like the trailblazing artists it highlights, the exhibition is doing an extraordinary amount of labour—from showcasing the early work of artists of colour only now getting their due, including Sonia Boyce and Lubaina Himid, to exhibiting rarely shown work from lesser-known artists like Poulomi Desai and Shirley Cameron. The curatorial vision may overwhelm audiences, with subjects including punk art, Black artist groups, domestic work, peace protests, AIDS, and lesbian communities, to name just a few.

Young acknowledges this ambition in her catalogue essay, noting 'In its attempt to present the activities of a wide-ranging network of women practitioners, Women in Revolt! is the largest exhibition to be staged at Tate Britain by some margin.' The Guardian reported that this is the first major museum survey on feminist art in the UK, so naturally there is a lot of ground to cover.

'Of course,' said Young, 'I have also had to edit and make selections, and the inevitable omissions and critical prejudices that play out across the galleries tell a story that for many will feel partial or inaccurate.'

Tate is far from the only institution carrying the torch. In September, the Royal Academy opened the long awaited Marina Abramović retrospective, unbelievably the first solo show of a woman in its Main Galleries. Last month, the ecological exhibition RE/SISTERS—a women-led show with about half the number of artists as Women in Revolt—opened at the Barbican to mixed reviews.

Female-led shows also feature prominently in London's 2024 programming. At the Serpentine, three out of five solo exhibitions—Barbara Kruger, Judy Chicago, and Lauren Halsey—will give women the floor.

Women in Revolt closes in April, before travelling to Edinburgh and Manchester. Another survey of British women artists will quickly take its place. Women Artists in Britain 1520–1920 (16 May–13 October 2024) will invite viewers to 'discover the artists who forged a path for generations to come'. Spanning 400 years, it will feature such disparate luminaries as Mary Beale and Laura Knight, all under the same umbrella of womanhood.

From this autumn to next, Tate Britain has taken on the gargantuan, dubious task of unearthing the 'great women artists' of British history, to borrow feminist historian Linda Nochlin's term.

One might wonder what British women were up to during the half century between the two exhibitions. Maybe another survey will bridge the gap. —[O]