Ai Weiwei on Liberty, ‘The Last Supper' and Lego Geopolitics

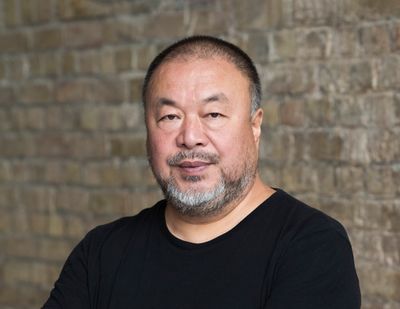

Ai Weiwei. Photo: © Ai Weiwei Studio.

Ai Weiwei. Photo: © Ai Weiwei Studio.

Ai Weiwei is not only one of China's most famous artists, but the artist who has most fully embodied the country's ambivalent opening to the world.

The potency and precariousness of Ai's willingness to speak truth to power is present as ever in the exhibition, know thyself (14 September 2023–30 March 2024) at Berlin gallery neugerriemschneider. The exhibition precedes the museum show In Search of Humanity (30 September 2023–3 March 2024) at Kunsthal Rotterdam.

Born in Beijing in 1957, Ai was just one year old when his father, poet Ai Qing, was sent to a labour camp in Heilongjiang as part of the Anti-Rightist Movement. His family was exiled to Xinjiang in 1961 where Ai Qing was made to clean toilets until Chairman Mao died in 1976, ending the Cultural Revolution.

Ai studied animation at the Beijing Film Academy before joining the Stars art group, a foundational force in Chinese contemporary art initiated by Ma Desheng and Huang Rui in the late 1970s. Their shows were radical, frequently closed by officials, and their members were persecuted in the Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign conducted by an especially conservative faction of the Chinese Communist Party.

In 1981, Ai became one of the first Chinese artists to study abroad, moving to the United States where he remained for over a decade and began experimenting with conceptual art—especially readymades—and picked up photography.

Returning to Beijing in 1993, he helped establish the East Village art community, where the Chinese avantgarde became edgier than ever—Zhang Huan, for instance, covered himself in fish oil and honey to attract flies while sitting naked in a public toilet for the work 12 Square Metres (1994), an effort to communicate the abject poverty he was experiencing as an artist and highlight the sanitary conditions of his environment.

Ai's own works range from lyrical celebrations of form and culture to pointed political provocations.

There are, for instance, sculptures created using ubiquitous readymades such as bike frames and wooden stools, and his millions of ceramic Sunflower Seeds (2010) made in homage to the snack eaten almost everywhere in China, their shells piled up in pyramids on footpaths, tables, and train trays.

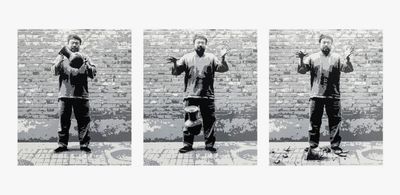

In his more impish mode, Ai famously smashed a Han Dynasty urn, photographed himself flipping the bird at state buildings, and snapped artist Lu Qing flashing her underwear in front of the Forbidden City (its title, June 1994 nodding to the fifth anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre).

He has created works from children's backpacks to commemorate the lives lost in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, and exhibited scans of his brain injuries and dioramas of his time in a secret prison—both attempts by Chinese police to prevent him from drawing attention to the shoddy building practices that made the earthquake so deadly, and to discourage active dissent against the state, more generally.

In know thyself, Ai combines his affinity for readymades with his indefatigable activism in a new series of Lego paintings.

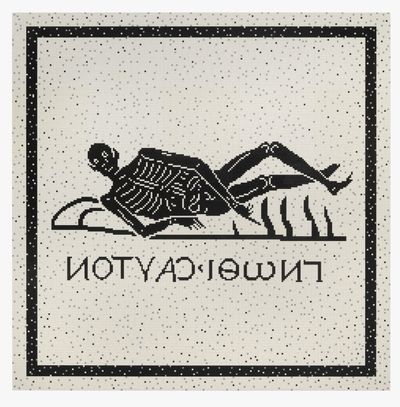

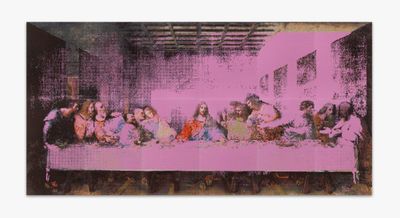

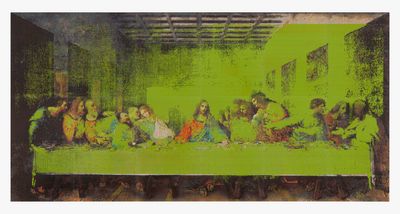

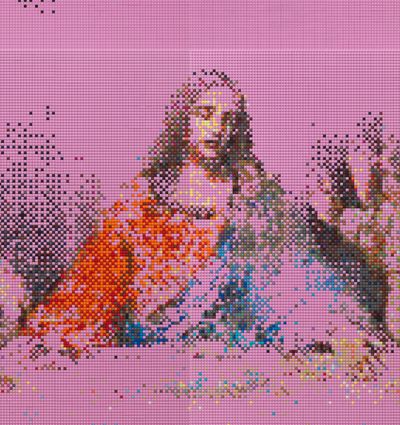

The titular work is based on a 1st-century mosaic (its tiles proto-Lego bricks) depicting a skeleton, along with the words 'know thyself' written in Greek. Others include depictions of The Last Supper (based on Andy Warhol's screen prints of the Leonardo da Vinci painting) that cast Ai as a laughing Judas, and a beautiful, 15-metre-wide rendition of Claude Monet's 'Water Lilies' (1897–1926) stained with an ominous black void, an allusion to the dugout he lived in as a child.

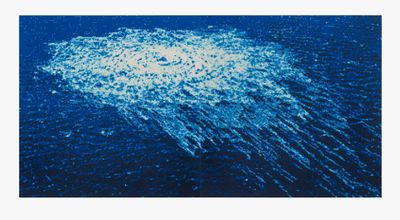

That black void is inverted in an explosion of white bubbles on a literal sea of blue in Nord Stream (2022), a work based on news photography of the attack on the Nord Stream gas pipeline. In this conversation, the artist elaborates on his drive to speak to the global political landscape, choice of materials, and relationship to Twitter.

SGThe most overtly political work in know thyself is Nord Stream (2022), which depicts massive amounts of methane bubbling up out of the Baltic Sea after pipelines that transport gas from Russia to Germany were blown up. Why bring attention to the Nord Stream bombings?

AWI grew up as an artist within a deeply politicised environment. My early years, subsequent experiences in New York, and life after departing China in 2015, have transpired amid constant shifts within the global political landscape and its pertinent themes.

What persists is the interconnection between people, their ideals, and the question of who takes advantage of others and who bears the brunt. The politicisation of our world endures, sometimes even magnifying and renewing its prominence.

There doesn't seem to be a swift solution to the crises confronting our planet; our issues span refugee crises, environmental crises, and human-induced ecological catastrophes, all affecting our living conditions. My attention is not explicitly fixated on these matters, but they pervade our lives unavoidably. Irrespective of our shared comprehension, political acumen, or perception of the world, these factors compel reactions to the phenomena that surround us.

In my capacity as an artist, I wield the language that captures my intrigue, crafting a means to express and provide a conduit through which others may sense and perceive. As you mentioned, I used toy bricks to create the artwork Nord Stream, which expresses the phenomenon of the burst Nord Stream pipelines.

The manifestation of natural gas from the ocean's depths to its surface appeared as a rare occurrence, much like a spectacle. It embodies the layered and complex interplay of geopolitics, international relations, and how humanity navigates these pivotal political dimensions intertwined with survival.

We are compelled to ponder: who orchestrated these actions, why accountability remains elusive, and who reaps the benefits from such consequential undertakings? These inquiries may never find concrete answers, thus rendering these news images akin to enduring wounds that refuse to heal. Toy bricks are a poignant means to portray such facets.

SGIn each of your four Last Supper works, the image is partially erased by a sea of colour, just as Andy Warhol's screen prints of the painting were lossy, giving up detail. You've included yourself in the paintings, standing in for Judas, but instead of looking worried, you're leaning back in your seat and laughing. Do you see yourself as a happy traitor? Is it possible to betray powers that aren't loyal to us?

AWIn the realm of contemporary thinkers, we encounter the imperative to reassess history that comprises human thought, culture, and politics. These historical elements are expressed within the boundaries of an era's context and its language, and the limits of comprehensibility both impose, which also holds true for me.

I deeply admire Andy Warhol's silkscreen prints. In his final days, he conceived 'The Last Supper' (1984–1986). By employing diverse mediums to tackle the same thematic territory, he accentuated the inherent attributes of each. This is precisely why I've chosen to communicate through the language of toy bricks—a form that encapsulates the pixels of our contemporary digital world and personal symbol.

My father relayed the narrative of Judas to me when I was a child. He wrote a long poem delving into the account of Judas' betrayal and Jesus' crucifixion. All of this finds its roots intertwined with my personal journey and memories of my youth. Both religious and political ideologies possess the potential to funnel individual thought along predetermined trajectories. As an autonomous thinker, I often find myself—consciously or subconsciously—assuming the role of a dissenter.

SGYou've been working with Lego for some 15 years now. Your most ambitious works using the material so far are the 'Water Lillies' (2022), which feature an ominous black hole, described as the door to an underground dugout in Xinjiang where your father lived in forced exile in the 1960s.

You've been imprisoned, beaten, and essentially exiled, too. There is trauma trapped in that hole—personal, familial, intergenerational, national, and cultural—but it's not something I often hear you talk about in your work. How are you able to make art in the face of trauma, fear, and loss, and how do those experiences inform the way you make art?

AWA person, akin to another manifestation of life or a plant, traverses the spectrum of existence adorned with tranquil interludes, as well as tempestuous moments accompanied by flashes of lightning. Indeed, adversities and traumas stand as an inseparable part of life. It all depends on how we define such terms.

An individual dwelling in times of peace and ease is not necessarily exempt from experiencing trauma. In fact, the very tranquillity and comfort might be trauma itself.

From my perspective, every human is a product of their unique personal journey. We hold the potential to transcend and elevate it to align with our comprehension of life, aesthetics, and ethics. Irrespective of how we live, as long as we are alive, we remain inherently entwined with our assessments of aesthetics and ethics. This intrinsic attribute is an indelible hallmark of our humanity.

It's not that we actively seek a certain kind of trauma or pain, but I believe that neglecting one's past and allowing it to fade into oblivion amounts to a disavowal of life's fundamental dignity and the elements that shape the essence of our existence; such a life stands marked by inherent deficiencies.

SGYou are one of the most active artists on Twitter (now called X), and it has been a crucial part of your practice, which to me has always been about radical transparency—bringing to light things that people can't see, whether that's injustices, nakedness, the interior of the Bird's Nest Stadium, or the cultural significance of simple things.

X is in serious financial trouble and many users seem unhappy with its new direction. This seems like a good moment to reflect: how have you used Twitter to extend your practice and will you continue to use it?

AWFirst and foremost, using a tool like Twitter hinges on the need to address specific problems, otherwise it would lose its meaning. During my time in China under high-level censorship, Twitter was a channel, window, and outlet. Without it, I would have been living in perpetual darkness.

For individuals living in societies subjected to stringent censorship and stifling enclosure, Twitter assumes the role of a beacon or the glimmer of a candle in their daily reality. Its importance is profound; people are compelled to safeguard their right to free expression with their life. Without this right, life relinquishes its paramount value.

Presently, the landscape of media is predominantly bifurcated into two archetypes. One encompasses those under oppressive regimes and pervasive censorship, like in China. Under this circumstance, the ruling regime brainwashes its people through media to enforce collective submission to domineering ideologies, thereby securing its own stability.

The other type of media embodies the notion of free press, predominantly prevalent in countries untouched by war. These media outlets have evolved into all-encompassing entities that blend information dissemination, politics, and entertainment into a mass spectacle. Information, to a great extent, has lost all notion of reflection and theory and merely resembles ruins.

This phenomenon—widely known as the media in the free world—abounds in sensational self-projection and distortion of facts, manifesting in pervasive fake news. Concurrently, it tends to relegate profound discussions regarding higher-level values to the superficial realm of entertainment, eroding their true significance.

Pervasive mass media, including Twitter, continues to be under the dominion of significant corporations. It bears an inherent 'original sin' as it directly serves the interests of these corporate giants. Within this framework, the platform capitalises on public ignorance to further its own products. This phenomenon remains a persistent reality. Even if the platform itself isn't directly promoting these products, the indirect influence is undeniable. These formidable financial entities and corporations, emblematic of individual ambitions and bloated influence, pose threats to humanity at large. —[O]