Bani Abidi: ‘What you see in my films is what I know’

Bani Abidi. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Schokofeh Kamiz.

Bani Abidi. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Schokofeh Kamiz.

A group of voices accompanies me in the exhibition. They are singing words I cannot comprehend, yet the warm tunes are familiar: folk songs, love songs, songs of longing. There are letters, too. They speak of the quotidian details of a soldier's life: the hardness of the war, sending money to the family, and longing for familiar landscapes, food, and the warmth of home.

Bani Abadi's Memorial to Lost Words (2016) is an installation based on letters and songs from Indian soldiers who fought in the First World War and are now buried in Zehrensdorf Indian Cemetery, 40 kilometres from Berlin. It is the closing piece of They Died Laughing, the first comprehensive overview of Bani Abidi's works in Germany, curated by Natasha Ginwala at Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin (6 June–22 September 2019).

Throughout the exhibition, photographs, videos, and drawings capture memories, moments, and encounters across Karachi, Lahore, Quetta, and Berlin, where the artist currently lives. In the photographic 'Karachi Series I' (2009), for instance, we see lovers, dwellers, market sellers, a woman ironing outside in the cool of the evening in Karachi; in the video and photographs that make up 'Section Yellow' (2010),

Pakistanis queue in front of what could be a checkpoint or an immigration centre; and in film The Lost Procession (2019), Hazara people participate in the procession of the Ashura in Berlin. It is the life of ordinary citizens that interests Abidi—not the heroic tale, but the poetry of the quotidian struggle for freedom of those who die laughing, or defiantly laugh in the face of death.

The show at Martin-Gropius-Bau reads as a commentary on current politics, state power, the dangers of nationalism, and the pitfalls of patriotic sentiment. It is also a homage to those who have been uprooted, displaced, marginalised, if not erased from the grand narrative of history; like the Indian soldiers in the deadly First World War, whose contribution has remained—until recently—unspoken.

Abidi creates a space where the stories of ordinary citizens—like the many journalists, activists, and those defiant voices in Pakistan society who have been silenced—can be told.

Against the backdrop of state power and geopolitical relations, in their often silent, yet solemn presences and dignified beauty, these figures seem to be enacting a refusal; refusal of the authoritative visuality that too often deprives them of their dignity.

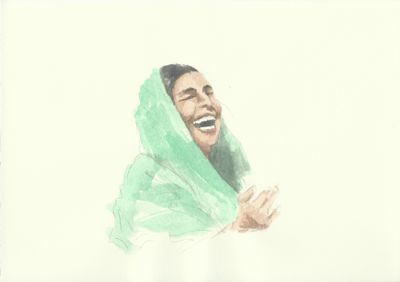

In the series of drawings that gives the show its title, these human beings are portrayed in the midst of hysteric, mad laughter—a laughter that supersedes the intimidating seriousness of the Law to show ecstatic abandon and defiance. Abidi is a collector of these absurd moments—these flashes of poetry, refusal, pride, and defiance.

One sunny morning in late August, I went to visit the artist in her Berlin home, where she welcomed me with a large, gentle smile. We talked about the topics in her work—from politics, cities, and gentrification, to identity politics—on view in Berlin at Martin-Gropius-Bau, and her upcoming exhibition at Sharjah Art Foundation (Funland, 12 October 2019–12 January 2020).

FBHumour plays an important part in your artistic practice, and it is also invoked in the titles of your two shows, They Died Laughing, which opened in June at Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin, and Funland, which will open in October at the Sharjah Art Foundation. Both titles evoke frivolity and joyfulness, yet in your work, this joy discloses the complex and absurd realities produced by power.

BABoth titles promise something very gay, frivolous, and joyful, but my work is not. They Died Laughing is very much about the representation of lives and histories, and civil society.

The focus of the show in Berlin is people, patriotic sentiments, and their relation to politics. It begins with the piece Shan Pipe Band Learns the Star Spangled Banner (2004), where a Scottish pipe band in Lahore, a remnant of colonial times, tries to play its own clumsy version of the American national anthem; and ends with the piece Memorial to Lost Words (2016), about the songs and letters of Indian soldiers who participated in the First World War.

In the historical novel The Weary Generations [by Abdullah Hussain], which inspired the title of this work, three Indian soldiers are alive in the trenches in a storeroom of ammunition. Death is everywhere around them, but they start laughing hysterically.

They joke about a buffalo being stolen in their village in India, and are laughing their heads off, in the belief that, if we have to die, we might as well die laughing. So, the act of laughing is a form of irreverence.

The watercolours that give the title to the show are based on the same idea, but there is another story behind them. It was after a political assassination of a Pakistani woman, someone we all knew, who hosted an event critical of the government in her café and was murdered after leaving.

Her death shook everyone: artists and journalists alike. Pakistan is very divided linguistically, in English and Urdu media.

The English-speaking minority has felt untouched by political oppression for the most part, but this proved that everyone was being watched. In the past ten years, many writers and bloggers who started to disappear, have been picked up for questioning by the intelligence services.

In the watercolours, you can see images of people laughing hysterically, almost mad laughter. In that laughter there is pain and there is defiance.

In one of your earliest films, Mangoes (1999), the simple gesture of eating a mango escalates into a show of patriotic pride and a simple conversation between a Pakistani and Indian woman, both played by you, turns into a ridiculous fight over different varieties of mangoes.

Mangoes was the first video I ever made, and I was thrilled by the possibility of communicating something so complex—like the relationship between Indians and Pakistanis—in two minutes. The sweetest moment was when I showed it to my uncle, who was 82 at that point and had no interest in contemporary art, and he screamed laughing, because he immediately grasped the joke.

I am mostly driven or struck by things that are absurd and can be mocked or satirised.

I believe there is democracy in humour, the same way that poetry is a democratic medium. A verse can get to you, because of the structure.

Poetry is like a joke; it sticks in your mind and can provoke thought. A funny joke is just fun at one level, but it can also make you think. I guess I am interested in that tension that humour generates. In my work, I try to capture the absurd moments in life.

FBFor your show at Martin-Gropius-Bau you made a new film, The Lost Procession, which in some ways is different from your previous works. Can you tell us more about the film and the process of making it?

BAThe Lost Procession was the hardest work to make. It adopts a quasi-diaristic, documentary form to represent the question of displacement.

When I saw the Pakistani Hazara people at the Ashura procession in Germany, I felt an immediate sense of closeness to home, and I kept thinking about the whole migration crisis in Europe and the discussion about how much Europe is suffering from this crisis and how generous the German government had been with all refugees.

But the displacement is so vast; people had to leave their homes and live in the most basic and often undignified ways. These migrations are the result of colonial interventions and global capital. They haven't come out of nowhere.

The film came from a sense of frustration I felt toward the way migrants are dealt with. Can people spend some time thinking about what's happened in different parts of the world, rather than focusing on what has happened to Germany and the rest of Europe? Of course, when I think of Pakistan, I don't blame foreign powers.

I am also very disgusted by the way the Pakistani state is dealing with internal politics. There is state complicity in making people flee their country.

I went to the procession in Berlin and I travelled to Quetta were the Hazaras come from, meeting people along the way. My favourite character in the film is the guy doing parkour and flipping on walls everywhere.

A film about him would have been more my style—it would have been a movie about feeling trapped and unable to escape—but since I am so invested in politics, I wanted to make sure that the people I worked with would be able to relate to my representation of them.

I don't generally work through any mode of social justice. I am mostly driven or struck by things that are absurd and can be mocked or satirised.

FBThe material of your work comes from experience and memories. I wonder what is the relation between the scripted and the real in your films?

BAElia Suleiman, my favourite Palestinian film director who made Divine Intervention (2002)—a film about the occupation that is reminiscent of the films of Jacques Tati and Buster Keaton—recently made a new film based on diaries he had collected over ten years.

He would sit in streets around the world and note down moments and encounters between people, collecting them without purpose until he felt there was a relationship between the notes and the world around him, which he then scripted into a film.

The process itself was not driven by a specific goal, and I could say the same about my work—it is the same way I harvest moments from my own memory that I find absurd or hilarious.

I try to translate and script the situation, although I always allow for the unexpected to take place. For example, we once simulated a traffic jam, and people from the neighbourhood came and started hanging out, and eventually became part of the film. It became this brilliant interplay of life in the city, the real—so to speak—and the fiction of my script.

FBYour show for Sharjah, Funland, takes the city as a point of departure. Can you tell us more about it?

BAMost of the works in the show at Sharjah Art Foundation will be the same as in Berlin, but the way Hoor [Al-Qasimi], Natasha [Ginwala], and I want to position them is more in relation to the history and geographical connections of that region.

Sharjah and Karachi are on two sides of the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf, and there is a whole tradition of human labour coming from Pakistan to the Emirates. So, we want to think of the city as a space of exchange and relations.

There was a nice work made by an artist duo in Karachi 30 years ago called Promised Land, which portrays the Gulf region as a 'promised land' for working-class Pakistanis. The choice of the title Funland is also in relation to this.

But it is also the name of a large video installation of mine from 2014. Funland sits between an amusement park and a destination; it is very abstract.

FBI recently re-read Jean Genet's Prisoners of Love, and your approach in some ways reminds me of Genet's poetic approach to the landless revolution of the Palestinians; the way he decides to focus attention on the shifting landscape, bodies, faces, traditions, and quotidian aspects of the fight.

In the book, the guerrilla campaigns remain more of a background spectre than an immediate spectacle, a 'distant gunfire under the stars' as Genet writes. Like Genet, your political commitment seems to be guided by an attention to the quotidian; by a series of questions and reflections on power, desire, forms, and language. I wonder what the role of writing and reading is in your practice?

BASomeone recently gave me Genet's book, but I haven't had the time to read it yet. Going back to Elia Suleiman, what I like about him is that he is a collector of moments, and it's hard to find someone who has such a unique way of telling the realities of Palestine.

For instance, I recall a scene in which two neighbours—a settler and a Palestinian—are staring at each other angrily. You stare at the scene for three minutes, and no one is saying anything, but you get it all. It's beautiful. It's the joy of performative moments, which also belongs to specific places.

Art can pull you away from the immediate moment; it pulls you back in history, makes you reflect, and it universalises things.

I have been living in Berlin for quite some time, but I don't feel I read the city. When I go to Karachi, I experience so many emotions within a 20-minute walk and I develop 7 million ideas, because I can read everything—I understand every single symbol around me, so it's like there is text popping up everywhere.

As I am looking around, there is so much transition that I can understand. I miss the possibility of distilling those moments in the flux of everyday life and then translating them into my work. Having said that, I also work a lot through memories.

There is so much that has happened in my life that I feel I can work with a reservoir of images in my memory. I really feel the need to stay connected to the city and the people in the streets of Karachi. There, I can get depressed and euphoric; it makes my heart beat faster.

FB'Karachi Series I' is both a homage and an investigation of the city and the people of Karachi. Can you tell us more about your relation to the city and what the urgency is behind this series?

BAEthnic and religious homogenisation has been underway in the country in recent years. Karachi is a natural port of the Arabian Sea that started growing into a city in the 19th century. Its history is way more complex than the 'unifying' self-definition of a young nation-state. 'Karachi Series I' is a way to think about the presence of communities that have lived in the city since before the country came into being.

As non-Muslims, they have somehow slipped out of mainstream life and are increasingly marginalised and invisible. I grew up in a time, in the seventies and eighties, when this was not the case. I went to a Parsi school, and Parsis are an ethnic and religious minority in Pakistan.

I want to assert my claim of Karachi being a crazily diverse city, of almost 22 million people. The characters in the photographs are actors and friends who were asked to pose on empty neighbourhood streets during Ramadan, when most Muslims are indoors opening their fasts.

They are deliberately facing away from the camera, introverted and anonymous at the same time. The work represents another instance when the cityscape became a willing and easy collaborator.

FBHow do you deal with the readings of your practice that frame it in the light of your Pakistani identity?

BAMy work has been often—but not exclusively—interpreted in this way, also sometimes in the German press. I want to make a strong point about the fact that my work is not about Pakistan. It's about power, security, and militarised architecture; and it's about the vulnerability of regular people.

We ought to be aware and assert the fact that such an identity-based reading of culture only happens when a work by a brown person is shown in a white space. A romance set in Paris is never perceived as being 'about' France, is it? What you see in my films is what I know and assume as my normative: the sounds, smells, landscape, and temperature . . . these are the details that help tell a story.

I am certainly not out to teach anyone anything about my country. My practice draws from a large spectrum of present and past experiences, and I hope to be able to speak to anyone who is interested in those ideas.

Of course, there are many layers in my work and its reading very much depends on the context in which it is placed.

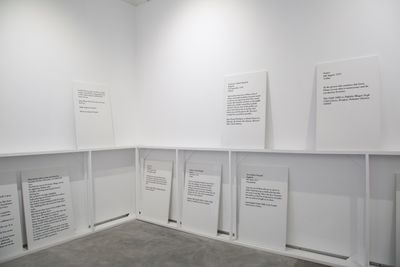

FBOne of my favourites works in the exhibition at Martin-Gropius-Bau is Memorial to Lost Words, an installation comprised of an audio piece and a series of letters written by Indian soldiers who fought for the British Crown in the First World War. What brought you to the stories of those soldiers?

BAThe work was commissioned by the Edinburgh Art Festival in 2016. Edinburgh is a city with more of 200 statues—of which one is a woman and one is a dog—and they are everywhere.

People sit on them, make out on them, or sleep on them. The curator Sorcha Carey wanted six artists to work on the idea of monuments and memorials. I was very interested in the idea of oral history—a reservoir of memories that are never written, but passed down through generations.

I was reading a novel about the First World War, and I was very touched by the stories of these young men who, at 17 years old, were forced to join the war without any idea of what was really happening or who they were fighting for; they didn't even have proper boots and uniforms in the first few months of the war.

There is this incredible scene in the book when they are making chapatis in the trenches. It's freezing outside, but they decide to make themselves a chapati, something that would make them feel closer to home. I got drawn into the life narratives of these men.

In Edinburgh, I chose a space that was supposed to be a debating chamber for the newly independent Scottish parliament, but it was never used.

I placed speakers on the benches playing Punjabi songs from a hundred years ago. The work and the location fitted perfectly since the space and the work were about speech and representation.

In Germany, there are another set of references: there is the Indian cemetery in a forest in Zossen, 40 kilometres south of Berlin, where the soldiers are buried; and there are recordings in the Humboldt Archive of the voices of Indian soldiers, that no one has bothered to translate.

An academic in the nineties listened to them and discovered that they were SOS songs; songs of distress, folk stories, and poems that expressed their distress and their desire to go back home, to their families and villages.

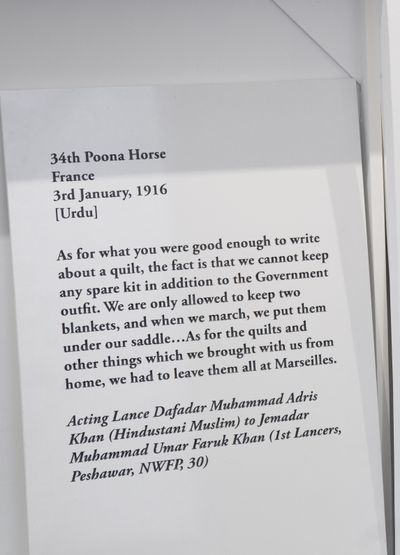

No one understood what they were saying. It's a very sad story. I also found soldiers' letters in a book titled Indian Voices of the Great War. Many letters in which soldiers criticise the war never reached their destination.

I gained access to the recordings and I had these songs recomposed and replayed as songs by a musician in Pakistan. At the beginning it was only the sound piece, but then I decided to add the letters because I enjoyed reading them and I wanted to add a layer to the work.

The women's voices sing traditional songs; one in particular says something like, 'don't take away our men, our society is crumbling'. It was important for me to make these voices heard and resonate in the space of the museum.

FBHow do you see the role and place of art in these difficult times?

BAArt can pull you away from the immediate moment; it pulls you back in history, makes you reflect, and it universalises things. In a way, things like the cyclicality of events and the language of cruelty locate you in civilisational history.

I think that the decision of an artist to invest all these energies in the realisation of a project is so endearing because there is no conclusion, yet you have some stupid, sweet, lovely, brilliant belief in what you're doing and you keep on doing it. Becoming an artist is a life choice, and a political gesture.

When I was growing up, there were all these black and white photographs of greasy-haired artists drinking and working in their dirty studios. And for me, the dirt in their studios was so sexy.

I loved it. I became an artist because their living space was very different from the living room of my parents' house. After graduating, I decided to go back to Pakistan and start teaching and making small films.

Going back was quite important to me. Now that I am away, living in Berlin, sometimes I feel disconnected. The distance brings out the magic of things that you were too close to see clearly.

But that distance can also depoliticise your practice. In contemporary art, people come from everywhere and share similar political beliefs, but it's a utopian bubble!

FBI often feel the same about living in a utopian bubble. It's beautiful and gives me a lot of freedom, but lately I have started to feel the need to reconnect and do something in Calabria, the place I come from.

BAPersonally, I am trying to be active from a distance. For instance, I recently mobilised opinion as part of an anti-gentrification movement in Karachi by making a video. Karachi is changing very fast, and the government wants to make the city 'prettier', so the first thing they did was get rid of old street markets, which have been there for 70 years. Many people's lives were affected by the new urban development policies.

So, when I heard that an important public park was going to be cleaned and turned into a private space for upper middle-class people, I put together a video that shows how the park is already a very vibrant public space, but just catered to middle and working-class people.

After two days of conversations via skype, I made a video, which really furthered the argument and people started sharing it and supporting the campaign.

For a long time, I thought that feminism was a class-based issue, where rich women were concerned about the 'poor other', the 'poor Muslim woman', and I was not interested in that kind of feminism.

As an artist, rather than opting to change my direction to only make activist gestures, I would rather be a creative activist in parallel. Creativity and brilliance are deeply appreciated in the activist space; for example, the amusing slogans that women created for the feminist march in Karachi on 8 March last year.

They made fun of Pakistani society, playing with cultural clichés. Their slogans were hilarious! Men were shaken by what was taking place in the streets, where thousands of women of many classes and ethnicities were dancing and laughing, walking together.

They had so much fun. It was the most beautiful expression of feminism that I have experienced. Humour played such an important role in disenabling power.

FBI can't stop thinking about the image evoked by Hélène Cixous in her famous text The Laugh of the Medusa, in which Medusa defiantly laughs at the absurdity of phallocentric assumptions; a laughter that recognises the fragility of life but also its ability to bestow life to that which appears death-bound.

BAFor a long time, I thought that feminism was a class-based issue, where rich women were concerned about the 'poor other', the 'poor Muslim woman', and I was not interested in that kind of feminism.

But then, after the opening of the show in Berlin, someone came up to me and said, 'you really bring men down—the way you make fun of them, their heightened sense of masculinity and their fragility'. And I said, 'hell yeah, I do have a feminist way of gesturing toward the world!' —[O]