Natasha Ginwala

Natasha Ginwala, 2015. Photo: Gaurang Anand.

Natasha Ginwala, 2015. Photo: Gaurang Anand.

In this conversation, curator, researcher and writer Natasha Ginwala discusses aspects of her curatorial practice and the upcoming Contour Biennale 8 (11 March-21 May 2017), staged in Mechelen, Belgium. Ginwala is a curatorial advisor for documenta 14, held this year in Kassel, Germany, and Athens, Greece.

Her recent projects include My East is Your West, a collateral event of the 56th Venice Biennale featuring Shilpa Gupta and Rashid Rana (6 May-1 October 2015); Mind Moves Matter at L'appartment 22 in Rabat, Morocco (5 June-30 September 2015); and Corruption: Everybody Knows..., an exhibition coinciding with e-flux journal's SUPERCOMMUNITY editorial project (11 November 11-23 December 2015).

Ginwala was a member of the artistic team for the 8th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art in 2014, and curated The Museum of Rhythm at Taipei Biennial 2012, a project that travelled to Muzeum Sztuki Łódź, Poland, in 2016. From 2012 to 15, Vivian Ziherl and Ginwala led the durational research project 'Landings' which was presented at Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam; David Roberts Art Foundation, London; neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst, Berlin; Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, and other partner organisations.

This conversation focuses on Ginwala's next curatorial project, Contour Biennale 8: Polyphonic Worlds: Justice as Medium. Contour Biennale, also known as the Biennial of Moving Image, was founded in 2003 as an organisation for showcasing film, video, installation and performance.

Between Biennale editions, Contour focuses on commissioning installations and organising public programmes across different venues and sites in the city.

This year's edition, curated by Ginwala, brings together 25 international and local artists and art collectives who work across art forms such as media, sound, performance, drawing, installation and publishing; including Basir Mahmood, Karrabing Film Collective, Eric Baudelaire and Rana Hamadeh.

Here, Ginwala reveals more about her background, research travels, advisers and some of the concepts that will be explored in Contour Biennale 8.

Congratulations on curating the upcoming Contour Biennale 8: Polyphonic Worlds: Justice as Medium. Could you tell me about your curatorial background and previous projects to date? I would like to know about how this grounding has shaped your approach to the Biennale.

I began my career at the intersection of three different kinds of disciplinary backgrounds: art history, political science and journalism. Writing continues to be a very strong component of my curatorial practice today, which is a result of being trained by a cultural critic, Sadanand Menon, in journalism school.

I then went on to study at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) School of Arts and Aesthetics [New Delhi]. JNU offers education in art history, but also exposure to curatorial studies, cinema and performance.

I feel that this grounding resulted in a specific kind of exhibition-making practice, whilst the discourse of practice is premised upon an understanding of time-based media, cultural history and performativity.

This was my first biennial experience, and I think it helped to push me to hone a different approach to curating—one that entangles artistic practices with intuitive modes of knowledge production.

TMHow did you build upon this initial and critical experience in India to inform your now international studies?

NGFollowing my studies at JNU I participated in the de Appel Curatorial Programme in the Netherlands, and realised that working as an independent curator wasn't simply about fitting into the social circuits delivered by the art economy.

Instead, I believed it was to do with mobilising concepts that are crucial to developing a politically nuanced understanding and aesthetically grounded approach to the present. I was asking myself, how do you construct a self-driven language as a curator? This was something that I feel we all were inspired to achieve through de Appel.

The level of collaborative dialogue that the situation provided brought us together to realise this. So, I feel a kind of a sudden level of international exposure combined with a level of interpersonal intimacy has characterised how I like to work. It provides me with a sort of necessary confidence to avoid narrow frameworks that restrict an evolving practice to a label—limited to a geopolitical capsule or point of origin.

TMHow did this international experience characterise your projects that followed? Who have you been working and collaborating on projects with since?

NGVery soon after the de Appel Curatorial Programme, there was an invitation to work with Anselm Franke on curating a segment within his Taipei Biennial in 2012. This was my first biennial experience, and I think it helped to push me to hone a different approach to curating—one that entangles artistic practices with intuitive modes of knowledge production.

I suddenly had this unique invitation where I was asked to offer a speculative model for a museum, and discern how this museum would deliver a narrative arc—which led to 'inventing' The Museum of Rhythm and considering the use of Henri Lefebvre's propositional tool: rhythmanalysis. Another pivotal moment in my practice was initiating the curatorial platform 'Landings' (1) with fellow de Appel alumni Vivian Ziherl.

TMHow did these experiences inform your research processes for Contour Biennale 8?

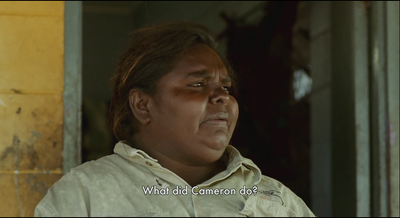

NGI feel that many practices that I was already engaged with for some years continue to shape Contour Biennale 8. Then there are those that I've recently encountered and have been excited to develop a conversation with. For instance, Vivian Ziherl and I have been working with the Karrabing Film Collective since 2013.

I've wanted to invite the collective to participate in a biennale that enables a comprehensive way of associating with their films, field work and processes which deal with survivance, the Australian government's 'intervention' and law enforcement policies since 2007, sacred sites and toxic environments—so the display is animated by the dynamic levels of thinking and producing.

Discussions with the advisors of this edition, artist Judy Radul and writer-theorist Denise Ferreira da Silva, have ensured that this exercise in biennale-making is one that stays aesthetically challenging and philosophically grounded.

Also, I've attempted not to 'hide' the artist list, but rather to try and contextualise these participating voices every step of the way.

The online journal which we are commissioning, Hearings, explores artists' approaches to language and their style of research, while also including art historians, poets and anthropologists to bring forth a solid discursive presence for the public and wider online audiences, even a year before the Biennale's opening.

When artists were invited to make site visits, we were introduced by city historians to Mechelen's medieval past, its relationship to legal history and to polyphonic music.

These visits were crucial in staging a way that the group of practitioners could spend time getting to know each other as well as the city, and for us to hypothesise together where this endeavour is headed.

Also, for a small-scale biennale, there is an increasing preference to keep the dialogue building among one another. It works because informality is a possible and desired condition. I'm keen to maintain that kind of informality, elective affinities and politics of care when realising any international art event.

TMI'd like to speak more about biennale models. I'm interested in specifically talking about modes of engagement within the space of a small-scale biennale, and the potential for intimacy and participation.

Can you tell us more about the Contour Biennale 8's online journal Hearings, and upcoming public programmes that will form part of the exhibition?

NGMaybe this is a generalisation, but it seems that even when one is working with a large-scale biennale model—like in Shanghai, as you did—it seems that when the format is thoughtfully broken down and shaped into a network of happenings and constellations of artwork, it will bear more intricate partnerships between the curator and other collaborators, artists and individuals from varied disciplinary backgrounds.

I think the biennale then starts to emerge as a 'meta-text', with many different chapters. That's what happened in Taipei, and I have come to appreciate that sort of model.

Within the 8th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, where I worked with curator Juan A. Gáitan, the question was about how one may insert a research inquiry within the fold of commissioned and historic artworks as a method to gaze upon 19th-century image-making, and how figures of colonial administrations and armchair scientists were constructing 'the world as image'.

So, it's not simply to say that it's big versus small; if at every step of the way one is thinking what to do with the large-scale exhibition, there are things to be talked about, challenged and inversed. I like the idea of the 'Infra-Curatorial' platform that your curatorial team used in the 11th Shanghai Biennale, upon invitation of Raqs Media Collective, which makes sense also in this conversation.

Returning to the core ideas behind Contour 8, we are not reflecting on the question of justice as an overriding thematic, but instead as a set of circumstances that address the legal horizon, the judicial infrastructures of society, the performative conditions of the trial and the presentation of the legal case through the active methodologies deployed by artists and collectives.

This way, I am enabled to challenge myself by engaging with these practices that continue their forensic analyses and planetary thinking—maintained as an ongoing inquiry with or without this Biennale.

The project considers how legal frameworks structure human behaviour through a strict regime of conformity when one is considered to act out 'against nature'.

We have remained sensitive to the architectural milieu of the judiciary and early governance in the Low Countries emblematic to Mechelen city. To provide an example, we are in conversation with Eric Baudelaire to exhibit his co-commissioned film, Also Known as Jihadi (2017) within the waiting room of the civic court, which was once the throne room of the Palace of Margaret of Austria.

Another key Biennale venue is the Alderman's House where the Great Council, formed as the highest court in 15th-century Burgundian Netherlands—gathered for its juridical proceedings.

We hope to move beyond the official history of presenting oneself before the law into agential conditions of addressing injustice, unconventional forms of conducting a trial, resonating with the records of lived testimony and unfolding acts of witnessing that remain resistant to the dominant structures of sovereign power and today's corporate state.

TMI want to discuss both the interdisciplinary aspect of the Biennale, and its engagement with collective practices like The Karrabing Film Collective, as previously mentioned. Can you tell us more about why these are important for Contour Biennale 8?

NGI would commence by mentioning inhabitants-tv.org, an online channel for exploratory video and documentary reporting run by Pedro Neves Marques and Mariana Silva. They are producing specially commissioned episodes hosted on the Biennale website.

I find their collective approach incredible as it proposes new interrelationships with image culture, digital media and investigative journalism, while also acting as a counter-measure to extreme right-wing news and opinion portals that currently infest the media landscape.

Council—an artistic institution developed in 2013 by curators Grégory Castéra and Sandra Terdjman with collaborators including Aimar Arriola—will continue their project, the Against Nature Journal, which considers penal codes that seek to criminalise homosexuality, curb sexual rights, and the corporeal politics involved in understanding the nature of nature.

The project considers how legal frameworks structure human behaviour through a strict regime of conformity when one is considered to act out 'against nature'.

The Karrabing Film Collective has such an amazing kinship structure that rejects the patriarchal genealogical record propagated and securitised by the white settler colonial state. There is so much to learn from the dynamics of this inter-generational group, right from messy-yet-egalitarian decision making to their phenomenal collective filmmaking.

Artists Louis Henderson and Filipa César are working together for the first time within the framework of Contour Biennale 8; they are not a collective but they have wanted to develop a film around the directional gaze of the lighthouse and its relationship to colonisation, the oceanic imaginary, as well as developing formats of satellite-based navigation systems. It is a work-in-progress that will continue over time and across upcoming institutional shows.

I like to assess the continuities in my practice.

TMIt sounds like it's a very layered approach, in terms of having practices that have a history of working together, whilst also placing some people together for the first time that might then develop a relationship. I want to expand on this idea of collaboration, but in in relation to your own team. Can you tell us about your Biennale team?

NGIt seems relevant here to mention that Contour went—in the time that I've been working for them—from an organisation with their own office and their own structure, to becoming part of NONA [Kunstencentrum NONA], an arts centre that includes a theatre and regularly programmes jazz music and other stage performances.

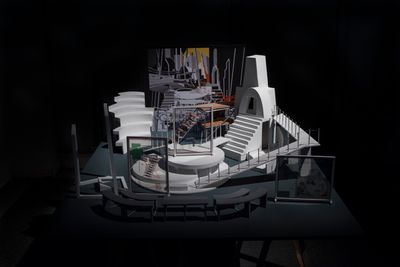

I think it's interesting that within our edition, Contour has gone through this transformation. The Biennale team is tiny, so we work very closely and share tasks. Contour director Steven Op de Beeck has a background in artistic training, so he is extremely involved in gauging the conversations around commissioning work and the finer details of its materiality.

Our graphic designers, Studio Remco van Bladel and exhibition architect,the Belgian artist Richard Venlet, have been keenly responding to the curatorial brief in a way that jazz improvisation often unfurls—their design has a metabolic language shuttling between the elemental and the complex.

The public programme, which takes place during the opening weekend (11-12 March 2017), is also a collaborative venture with the Dutch Art Institute in Arnhem, Netherlands. Jointly curated by writer and critic Rachel O'Reilly and myself, it is called Planetary Records: Performing Justice Between Art and Law, and is set up to include film screenings, lectures, conversations and performance to unpack some of the key arguments and open questions we are grappling with.

The entire student body and tutors of the Dutch Art Institute as well as other educational programmes like de Appel Curatorial Programme will also be joining us in Mechelen. My hope is that we resound as a temporary community, provoking and listening to each other, rather than being biennale zombies.

TMCan you tell me more about where you travelled to during the research period of Contour Biennale 8? How did your experiences inform some of your curatorial choices for the Biennale?

NGFor the curatorial research, I was conscious about making use of the resources the Biennale has, while planning travels that led to spending time with a range of artists in their studio and in their cities, rather than trekking to international biennale openings and exploring unfamiliar geographies in an accelerated way.

I visited Australia to attend Vivian Ziherl's Frontier Imaginaries opening in Brisbane, and we visited Stradbroke Island to meet with aboriginal activist-leaders. Further, I also met with some of the artists participating in documenta 14 and spent time in Belyuen Shire [a local government area in Northern Territory, Australia] while Karrabing Film Collective were also shooting their latest film.

Another extensive trip that brought hugely inspiring perspectives was to the Caribbean, where I was invited for a residency organised by the Davidoff Art Initiative in the Dominican Republic.

I spent time at Beta-Local in San Juan, Puerto Rico and had a chance to meet several fantastic artists, among them Beatriz Santiago Muñoz who will be part of the Biennale. With artist-filmmaker Louis Henderson and Paolo Chiasera, I visited Port-au-Prince where we were hosted by two of the amazing founders of the Ghetto Biennale, Leah Gordon, André Eugène, as well as other members of the Haitian artist collective Atis Rezistans.

I think the biennale then starts to emerge as a 'meta-text', with many different chapters.

TMCan you tell us about what is next for you, following Contour Biennale 8 and documenta 14?

NGI'm working toward a project next January at ifa Gallery in Berlin on the invitation of the gallery's director Alya Sebti. The intention is to address the phenomenon of riots as a deeply historical as well as contemporary neoliberal formation, and as a space of trauma and constellation of charged bodies.

There remains something elementally destabilising and irreparable in the question of the riot. When speaking with Queensland artist Vernon Ah Kee last year, he called the riot a 'tipping point' and a spill over of energies.

This is how I wish to consider the riot as a zone of ferment, which incessantly leaks into the body politic and remains actively embedded in realigning social relations.

I like to assess the continuities in my practice. It feels as though the exhibition and publishing project with e-flux, which surveyed corruption as a planetary figure, is conjoined with the current efforts in discussing justice as a media archaeology with Contour Biennale 8, and now this upcoming linkage with riots—a trilogy around the disturbing pathology of our times.—[O]

(1) 'Landings' (2012—2015) was a durational project at the intersections of land history, geological time, explorations of rural modernity, resource extraction and corporeality. It was conceived by curators Natasha Ginwala and Vivian Ziherl.