Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung

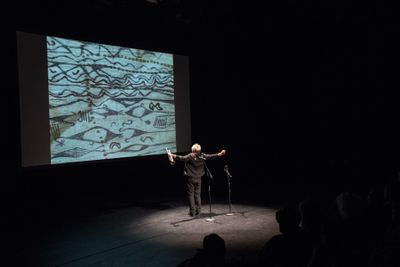

Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung. Photo: © Raisa Galofre.

Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung. Photo: © Raisa Galofre.

Curator Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung has been living on and off in Berlin since 1997, where he founded the self-organised art institution SAVVY Contemporary–The Laboratory of Form-Ideas in 2009.

Early exhibitions include Understatement/Hyperbole (13 February–13 March 2010), with works by Soavina Ramaroson and Petra Lottje; Arctic Heat (10–30 October 2010), which presented 17 artists from Lapland and the region of Oulu, including Kalle Lampela and Steve Pratt; and Perspectives on In/Outside (4 December 2010–2 January 2011), which combined structural designs by Van Bo Le-Mentzel and paintings by Pierre Juillerat.

In its third year, SAVVY was awarded EUR 30,000 from the Berlin Senate Department of Culture, which allowed Ndikung to move the space from its storefront in Neukölln to a 400-square-metre ex-power station built in the mid-1920s by renowned architect Hans Heinrich Müller.

In 2015, SAVVY Contemporary finally settled in Wedding in a former crematorium—Berlin's oldest—built in 1910. The institution has always engaged with some of the most recognisable names in contemporary art, including Hassan Khan, Candice Breitz, Hito Steyerl, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Kader Attia, Otobong Nkanga, Bouchra Khalili, Julieta Aranda, Ibrahim Mahama, and Barthélémy Toguo, to name but a few.

As a curator who explores new methodologies that reimagine new forms of exhibition practice, Ndikung's projects are often organised like laboratories focused on creating new ways of seeing art and experiencing the world. In August 2016, he curated The Incantation of the Disquieting Muse, an exhibition of work by 19 artists and 1 collective—among them Georges Adéagbo and Haris Epaminonda—that explored 'witchery' as a tool of future-making, while looking at its expressions, from idioms to chants, as manifestations of cultural, economic, political, historical, medical, technological, or scientific infrastructures on which parallel realities, and futures, are built.

The Incantation of the Disquieting Muse is but one example of Ndikung's passion for creating counter-canons that disentangle from the use and abuse of historical canons in the art world. One exhibition project that exemplifies this approach is Geographies of Imagination (13 September–11 November 2018), which Ndikung co-curated at SAVVY Contemporary with artistic co-director Antonia Alampi, featuring 17 artists, including Heba Y. Amin, Michele Ciacciofera, Anna Binta Diallo, Oscar Murillo, and Rossella Biscotti.

The project refused to submit to a particular ethnic or geographic category, asking instead how it might be possible to find common ground and a sense of planetary belonging. This question seems to define SAVVY Contemporary's modus operandi, and by association Ndikung's.

This year, SAVVY Contemporary celebrates its tenth anniversary, and offers an impressive line-up of exhibitions and projects that will develop into 2020, covering a broad range of topics, from the history of anti-psychiatry (Ultrasanity. On Madness, Sanitation, Antipsychiatry and Resistance, 20 December 2019–26 January 2020); a commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus that poses critical questions regarding the Bauhaus institution, and how its history has been written (January–November 2019); and Residing in the Borderlands, a year-long monthly film series that will consider Berlin as the centre point for reflections on nationality, residency, and belonging, with future editions involving names such as Amelia Umuhire, Daphrose Ndakoze, and Liz Rosenfeld.

Under the umbrella topic, The Invention of Science, SAVVY Contemporary will present five chapters of exhibition programmes and discursive research platforms exploring the history of science and its relation to the history of colonisation and capitalism, and is also collaborating with Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) as part of its engagement with Archive Außer Sich, a project by Arsenal—Institute for Film and Video Art that explores the necessity to create better infrastructures for existing archival projects.

Beyond SAVVY Contemporary, Ndikung is representing Finland at the 58th Venice Biennale (11 May–24 November 2019) as part of the Miracle Workers Collective, a new alliance that consists, among others, of curators Giovanna Esposito Yussif and Christopher Wessels, artist/activist Outi Pieski, and artist/designer Lorenzo Sandoval. He will also curate the 12th edition of Bamako Encounters in Mali (30 November 2019–31 January 2020) and the 2020 edition of the sonsbeek exhibition in the Netherlands (5 June–13 September 2020).

In this conversation, Ndikung discusses his stance on curatorial practice, outlines his idea of an exhibition as a jam session, and elaborates on the notions of post-otherness and dis-othering.

MSI wanted to ask about Geographies of Imagination, an exhibition that considered modes of dis-othering in a way that recalled the 10th Berlin Biennale, We don't need another hero (9 June–9 September 2018). Could you elaborate on the ideas behind Geographies of Imagination?

BSBNWell, we have indeed been writing and making exhibitions around these topics long before last year's edition of the Berlin Biennale. Geographies of Imagination did suggest the urgency of moving beyond the topic of otherness, but at the same time it emphasised the impossibility to do that without acknowledging that the processes of othering are ongoing and adaptable with time and space.

It's too easy to say 'It's over' and move on, while it's actually not so easy to cut ties with the processes, since they have to be re-elaborated and understood before they are done away with. That can only happen by going back to the history of othering in order to know how it might be overcome. One of the biggest crises of our times is the fact that Édouard Glissant's call for opacity has been mistaken to mean obscurity and erasure.

MSWhat about the challenges of this approach? You might be savvy, but the audience might not be savvy enough to understand this complex way of engaging with the notions of othering, post-othering, and dis-othering. Your projects—like Geographies of Imagination—could easily be categorised as identity politics.

BSBNFirst of all, I want to start by acknowledging the people who made this exhibition happen. They include the SAVVY team, especially my collaboration with Antonia Alampi, as well as partners in Austria, Belgium, Poland, and other places, and the artworks that came from all over the world.

I'm not afraid of identity politics. The issue is when identity politics gets caught up in an economic model and becomes commodified, then it becomes a facet again. Identity politics is what we're always dealing with. It's always about identity. Always. Economics is always about identity. Identity is also class. We are always negotiating identities. The question then becomes how not to let yourself be ascribed a certain identity, and a singular one for that matter. I am willing to go along with Glissant's notion of 'consent not to be a single being'.

It's important to say that I do not belong to a group of curators that underestimate their audiences. In many cases, the audience is miles ahead. In doing SAVVY Contemporary for the past 10 years, and making exhibitions now for 15 years, my experience has been that audiences are willing to come with you, if you are willing to challenge them. So I would say that audiences are savvy enough and capable of feeling us, and they did with Geographies of Imagination.

But to come to the crux of your question, it is by now common knowledge that the prefix 'post' is not to be read literally as meaning 'after', but rather, as Homi K. Bhabha proposed in The Location of Culture (1994), it must be read as the 'beyond', which Bhabha pointed out was neither a new horizon, nor a leaving behind of the past.

It is more to be understood as an in-between space wherein the past and future are constantly negotiated. So this is the way the 'post' in 'postcolonialism' has to be understood, as indicating a transition; a space of negotiating the transcendental unison at that moment of looking at what coloniality means, and negotiating the thereafter.

Therefore, the 'post' in 'post-otherness' would also be the tackling of what 'otherness' actually was and is, and how it could be negotiated in this beyond space. The notion of post-otherness was conceived in the text 'The Post-Other as Avant-Garde', which I wrote together with Regina Römhild for We Roma: A Critical Reader in Contemporary Art in 2013.

What Geographies of Imagination proposed—and what I propose now—is a dis-othering that hopefully goes a step further. Dis-othering came to life as a possibility of situating post-otherness within institutional critique. It was a response to an invitation from BOZAR Brussels, which I considered an effort to other, an effort to put one in what Michel-Rolph Trouillot called 'the Savage Slot'.

How do we deal with what society demands of us? What we do is play with the refusal of not being that other; we do not only sit in that space of refusal. Both I and SAVVY as a whole have been practising this double negation for ten years now. So the seven key steps of dis-othering that we proposed were a way of finding words and postures of dealing with constant efforts to other.

MSA related example of an endless process of undoing is how racism and black identity is dealt with in North America in comparison to Africa. As we discussed prior to this interview, the danger of the global focus on the African-American condition is that, compared to Africa, which has historically been dealing with the question of colonialism and racism for much longer, North America is in the phase where blackness is defined by racism, discrimination, and white supremacy, and those opposing these conditions are still trying to figure out a way to break out of being defined by them.

BSBNRather than a comparison, what I am more interested in is looking at the relationship between the struggles on the African continent and struggles in the so-called New World. It is true that the struggles on the continent have been going on for much longer, but it's also true that these struggles are connected and inform each other.

What informed the Présence Africaine—which was founded in 1947 in Paris by Alioune Diop with the support of Aimé Césaire from Martinique, Léopold Sédar Senghor from Senegal, and Richard Wright from the U.S.A.—was also very much influenced by the energies of the Harlem Renaissance that happened in 1920s New York.

At the same time, the Harlem Renaissance would not have been possible without the voice of somebody like Marcus Garvey, who was Jamaican. These movements are tied in important ways, but we need to look beneath the surface to understand the way they are tied. Movements of resistance are not always connected on the historical surface. What I think is a rather new phenomenon is the idea—which a lot of our African-American brothers and sisters have unfortunately bought into—of America First and of the American Dream.

What I am also trying to suggest is that the discourses of Blackness and the Black Atlantic in the last 30 years or more have been championed by important and very rich North American and Anglo-Saxon universities. In the past years, I have been interested in shifting from Black Atlantic-centrism to looking at other notions of blackness and black diasporic existences.

The Indian ocean, for example—what scientists have called the oldest cultural continuum in human history—seems to be an interesting space for research. Natasha Ginwala and I have been researching trade routes, syncretic languages, cultures, and beings that make up the Indian Ocean reality.

In April 2018, I was in Brazil for the Echoes of the South Atlantic conference. It was important, but I think we need to shift the discourses again and revisit the work of someone like Ivan Van Sertima, who wrote They Came Before Columbus (1976). Going back to your question, the answer is that the internalisation of hate or othering is very difficult to get rid of.

As Ngugi Wa Thiong'o put it, we need to decolonise our minds—and this is no easy thing to do. It is only then that one is able to see oneself properly, and not through the prism of those who have othered you. Until then, one will define oneself through racism, discrimination, and white supremacy. Still, we need to do all within our possible best to understand and fight racism, discrimination, and white supremacy within our societies.

MSWhen people think of SAVVY, they think of a space where they're guaranteed an understanding of African 'contemporality'. The way you have done this in the last ten years has been by contextualising Africa within the rest of the world. Could you discuss this approach? How do you see this developing further into the future?

BSBNBecause I'm African, everything I do tends to be qualified by others as African. I do not bother to dispute this because what we truly want to do at SAVVY Contemporary is to think from an African perspective—to think from a conceptual space that is African and of an African world, as world history is entangled with African history.

When we do exhibitions, we work with people from different parts of the world. Unlike many other institutions that focus on the Euro-American axis, we look beyond those lines. We also work with artists and critical thinkers irrespective of their stardom.

That hardly matters to us. Rather, what is important is the depth, breadth, relevance, and reflectiveness of their practices. We are really interested in multiple and complex epistemologies beyond the realms of academia. In the next years, we hope to stay on our toes and not get too comfortable. We hope to be able to dig deeper, and come up with challenging questions for our time. We hope to find the means to experiment more on curatorial and artistic formats, and most especially we hope to stay relevant.

MSDo you think curatorial work can be compared to algorithms? This is not to say curatorial work is mechanistic or predictable, but that it considers how curatorial innovation, once presented, gets absorbed and replicated by others, be they curatorial agents or institutions. In short: new and successful curatorial models take on an almost algorithmic role when they are replicated by others in the field.

Of course, part of implementing curatorial algorithms is localising them. And I think what the curatorial collectives at SAVVY have been providing is a new model of curating. What do you think are the core components of this new model, which you have developed as the head of SAVVY's curatorial projects?

BSBNI really like the idea of curatorial algorithms. I think it is beautiful. Curatorial practice is a discipline, and every discipline has its own set of rules, practices, and methods that amount to groupings of algorithms. It should not only be seen through mathematics or computation, but something larger. In general, algorithms entail methods, rules, and structures; and curatorial practice has to do with algorithms.

Now, we, as in all of my colleagues—Antonia Alampi, Elena Agudio, and the rest of the group—belong to a genealogy of people who have done stuff before us, which we need to appreciate. People like Okwui Enwezor, Salah Hassan, Olu Oguibe, Bisi Silva, Adam Szymczyk, Wim Beerens, and Harald Szeemann, to name just a few, from whom we've learned directly or indirectly.

Something that is clear to us is that curating is a discipline that converges many others. We are trying not to indulge in what Lewis Gordon called disciplinary decadence. Curatorial practice, the way we see it, must always transgress the set frames. It must also be a space not only of aesthetic propositions, but also of socio-political deliberations; curatoriality must also reflect what my colleague Elena Agudio calls extra-disciplinarity.

As you might know, my background is in medical biotechnology. My curatorial practice is naturally informed by this. I think of cultural practice as a jam session. How can we imagine an exhibition as a jam session? It's two in the morning. We're in a bar, ideally not in New York, but in Johannesburg or somewhere else. And people just come, have drinks, some drunker than others. Some pick up the instruments that they really know how to play, some don't really know how to play any instrument at all. As they play, they negotiate a practice of listening. To me, this is what the curatorial is and what we've been trying to cultivate at SAVVY.

We listen to each other and to the people after we've seen what is happening on the ground. We tell the professionals, 'Okay. You can play better than the others, but we have to meet somewhere to make other people that are here in this 2 am session part of it.' The idea of the exhibition as dealing with certain objects in a particular space within a particular frame of reference is, to us, extremely outdated.

At SAVVY, we do what we call 'invocations', as extensions of the 'space' of the exhibition, where we invite scholars such as Hamid Dabashi to speak, but also sound performers like the Drummers of Joy, or other forms of performativity. Of course, it's more than just some guys playing drums—rather, it is about sonic epistemologies. As Babatunde Olatunji once said, the drum is a living being because it's made up of the trunk of a tree and the skin of an animal.

So, it must be speaking. My thinking about curatorial practice is highly framed by a thinking of the sonic, in the sense that even though it might not involve words, it tells you something just as much as the body does. If we're interested in sonic mediums like radio, it's because we're interested in untraining the ear, and imagining ways of making exhibitions in the ether. When we do exhibitions, we try to activate all senses and beings that accommodate the spaces. It's like waking up certain ghosts.

MSThere is a lot of interaction between curators at SAVVY. The normative practice states: 'I'm the curator. This is my project and nobody else is going to get the limelight.' A lot of projects that you have instigated are about working together with other curators where the outline of authorship gets hazy, if not altogether disappears.

BSBNIn the so-called 'art world', people act like explorers. They act like Christopher Columbus. They want to be the one that discovers shit. In most cases, most of them discover nothing new. This is actually about the politics of referencing. If you look, how many institutions are working on unlearning; unlearning this, unlearning that. Three years ago, we did a big project on unlearning at SAVVY.

While we were doing some unlearning, we wrote and published a lot about this topic and referenced the people—like [Gayatri Chakravorty] Spivak—who worked on unlearning before us. Now people come up and unlearn this and that, but they don't make references, because they want to be the ones who are known for discovering the concept. But this doesn't take you anywhere.

We are proud to say that we build on the work that was done before us. You can think of it as a notion of ancestry. That's why I have respect for someone like Fred Morton. He said, 'I don't even want to sign books with my name anymore because the things I am writing are very much things that were discussed by others in the form of music. In the form of improvisation.' That's why we have the protocol of the academy of the fireside.

For instance, I'm no longer interested in quoting Foucault because I have to quote my grandfather who told me a story by the fireside. I have to think about those politics of referencing, and what is legitimised. In making exhibitions, some curators want to be 'the lonesome cowboy or cowgirl', but we at SAVVY would rather work and walk together, while each person has their own responsibilities and load to carry.

MSSAVVY is not a centre for activism, nor is it a political party. But with the rise of nationalism, white nativism, and sociopolitical intolerance, how does SAVVY as an institution of art and culture fit into the political landscape of a dangerously changing Germany?

BSBNIt's true that SAVVY is an art and cultural space, but we are made up of human beings. Human beings that are part of society. It's a myth that any art space can cut itself from what is happening in the rest of society. We are all political entities, whether we like it or not.

It's not only the fact that it's a responsibility for us to respond to the surrounding political world. We do not have the privilege and the luxury not to deal with political issues, because we are political. We are part of the polis. We're living in a very difficult time. I come from Cameroon where 40,000 people, from the part of Cameroon I come from, had to flee the country in one year. And the number is rising. We all see what is happening with Modi's government in India.

When Angela Davis was in prison, James Baldwin wrote a letter to her in 1971 that included two important points. The first was the idea that there is no space left in which to be neutral, and that we have to take a position. The second point was that if they come for somebody else in the morning, I cannot afford to stand there and assume that this is just happening to you because you're different to me, so they will come for me in the evening.

On a personal level, last year I was on the street with my son who was seven years old at the time. I was attacked by a guy who pepper sprayed me in the face, while my son stood there watching him. What does that do to a seven-year-old kid? One needs to act.

I don't like these comparisons, but things that happened in 1933 constantly come to mind. We have to act on a daily basis. One reason we have a space like SAVVY is because we cannot only respond to what is happening on a personal level—we need to act collectively.

We also need to create safe spaces for ourselves and others we care about. Of course individuals are important, but we have to think about ourselves as individuals that form part of a milieu; an ecosystem.****—[O]