Caroline Rothwell: Follies of Industrialisation

Courtesy the artist. Photo: Jenni Carter.

Courtesy the artist. Photo: Jenni Carter.

Once described as 'a kind of nature on acid', Caroline Rothwell's bright-hued sculptures disguise sinister realities. Rothwell, whose father was an industrial chemist and mother she describes as a 'street botanist', combines scientific inquiry with her artistic output, which includes sculpture, installations, drawings, and paintings.

Attuned to the 'contemporary conundrums' that shape the world, Rothwell unpacks the past to consider the future, luring viewers in with opulent forms and colours. These decorative elements embody the absurdity of grandiose moments on the timeline of industrialisation. One such act includes geoengineering—the technological processes that intervene in the earth's climate system to counteract the effects of climate change.

In her own attempt at geoengineering, Rothwell collects carbon, transforming the soot into pigment—a process that recalls the Victorian use of 'lamp black', where binder was added to soot from oil lamps to create ink. In works such as Habit (2015)—a large-scale mural on the wall of Temple University in Philadelphia—Rothwell rendered the forms of Juncus alpinus, an endangered plant endemic to Pennsylvania, that faded with the elements, reflecting humanity's impact on nature.

In recent paintings, the artist has incorporated soot left behind from the devastating bushfires outside of her home in Sydney, creating descriptive textures and surfaces that recall the contents of curiosity cabinets, and the human compulsion to collect and control nature. These canvases are showing at Yavuz Gallery in Singapore for her solo exhibition Corpus (20 March–18 April 2021), alongside a series of new hybrid sculptures, reflecting on the relationship between humanity, industrialisation, and nature.

Over in Sydney, a series of the artist's 'Carbon Emission' animations will be projected at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia as part of The National: 2021: New Australian Art biennial (26 March–22 August 2021). Concurrently, at the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney, Rothwell is launching Infinite Herbarium, a multi-channel projection and app created in collaboration with Google Creative Lab, that will allow participants to photograph and learn about plants, creating their own hybrid specimens in the process.

In June, the artist's solo show Horizon opens at Hazelhurst Regional Gallery (26 June–5 September 2021), exploring the politics of nature, history, and time. Then, in September at Tolarno Galleries in Melbourne, the artist continues her reflections on the interconnection between nature and humanity with a series of new paintings and sculptures.

In this conversation, Rothwell reflects on her latest work and the themes that drive her artistic inquiry.

TMThe palette of your latest hybrid sculptures at Yavuz Gallery seems lighter than before. What new trajectories have you taken with these?

CRThe exhibition in Singapore is called Corpus. Over the last few years, my work has looked at the connection between humanity, the botanical, and the industrial. I seem to spend an awful lot of time in plumbing supply stores looking at taps, drains, and ducts, which take on these bodily references.

We're living in high-speed history at the moment. It's so fast. And there are all these battles raging for control—for the weather, the atmosphere, for our ecosystems.

I was very interested in thinking about them as the infrastructure of our urban world; thinking about this unseen territory that runs through the structure of society—all the piping systems for water, gas, data, and so on. I'm interested in those systems being the unseen infrastructure of our spaces.

I was putting drains, ducts, and chains into sculptures, alongside the botanical and human references of tongues and hands, casting them into the work, wrapping around plant forms, and it just felt logical to start playing with a different palette.

TMThe exhibition also includes a series of paintings on canvas, and chair sculptures—what is the connection between those and the hybrid sculptures?

CRThe show began with me thinking about our relationship with the natural world over the centuries, since the start of industrialisation. I spend a lot of time looking at archives and museum collections and how the natural world is represented. The work is also looking at cabinets of curiosity, and how the European colonial connection with the landscape of 'elsewhere' began through curiosity and then consumption.

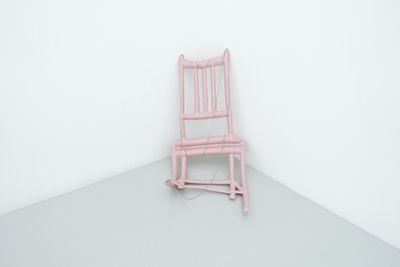

Somehow, integrating the tongues and hands into the plant forms took me into a much more vernacular space; this 21st-century moment, and into this current moment of isolation. Suddenly, the chair became a body, and a slumped cast chair took on new significance.

In terms of the natural world, I was making these pieces where I was looking at birds of paradise and how they were represented in European collections after traders started going to Southeast Asia. They would see these incredible birds, kill them, take the bones out, and send the skins back home, where people only understood the creatures from their skins and assumed they floated through sky, were boneless, and existed on dew.

I'm interested in that lack of understanding; that authority of image and the ripple effect of all this on where we are now. So I started making these birds; not trying to get them 'right', but just reflecting on the history.

I decided to use chairs as plinths for these works, so some of the birds sit on the back of real chairs, and their beaks are holding a compass or windometer, reminding us of other forces that exist over our shoulder.

TMA lot of your works have these rococo, very opulent details and forms. In a way, the hardware elements in your latest sculptures are stripped-down versions of those.

CRI am really interested in those opulent visual signifiers of the 1700s, like cartouches and motifs of adornment that assume some kind of spatial authority but are a detached architectural folly. Maybe that era was when the Western disconnect with the natural world began—what followed was curiosity, collecting, colonisation.

Curiosity has a complicated history in the West, but I think it also has great potential to build connection.

My first 'Carbon Emission' animation portrayed a cartouche and included botanicals and tongues and clouds as well as those ornamental references. I've been using carbon emissions in drawings and animations for a while, and I've been tracking data relating to carbon emissions over time and looking at how many parts per million of carbon dioxide are in the atmosphere now in comparison to, say, the 1780s. In the 1780s, there was something like 280 parts per million of CO2 in the atmosphere, and now there are over 400 parts per million, and rising.

I'm fascinated by that timeline, tracking our environmental position through these historical signifiers of time. I'm interested in an aesthetic to draw in, and even though the work can seem quite playful and beautiful, there's always this double edge.

Elements like the readymade hardware integrated into the sculptures, and the production process, keeps the vernacular in the present alongside the conceptual framework. I'm also really interested in the act of making sculpture and all the dialogue that builds along the way with the process.

TMSpeaking of processes—on your website, it's written that you use 'self-devised fabrication methods' to create your works. I'm curious to hear more about what those entail.

CRThe fabulous curator, Anne Loxley wrote that and I think the 'self-devised' comes from being a girl.

When I was young, I was never taught how to use tools the way the boys were, but I was always fabricating things. I was building little houses for beetles, I was collecting, I was just making stuff.

My dad was an industrial chemist, so I melted lead and mixed elements, but I think the fact that I was never introduced to the tools informed my methods—it wasn't necessarily an act of rebellion, it was more that I didn't know anything else.

I was completely free from thinking about what sculpture might be. So for instance, the sewing machine is an incredible fabrication tool—it's an amazing way of creating form and volume when you don't have access to jigsaws and angle grinders.

That kind of semi or pseudoscientific process has always been an anchor for me. There's a structure to it but also an absurdity, like collecting industrial carbon emissions to make inks with.

I'm also really interested in the meaning behind processes and materials. When I was thinking about evolution and industrialisation, I was considering how to represent these funny little ignored, yet foundational elements of the natural world, such as endangered insects and plants. What happens if I start to use the material of their demise to represent them, and then also use that scientific methodology of noting down details about the collected carbon emissions and put that into the artwork?

That kind of semi or pseudoscientific process has always been an anchor for me. There's a structure to it but also an absurdity, like collecting industrial carbon emissions to make inks with.

TMI find it interesting that you made your first major bronze work, Transmutation—now housed in the collection of the Art Gallery of South Australia—in 2010, quite late in your career considering your training in sculpture. I was wondering about your relationship to the canon of sculpture, and those traditional materials and notions of what sculpture should be?

CRI am really interested in the monument and the anti-monument, and I'm also interested in the light touch of production. Before making that bronze, I worked on very large inflatables, so I could actually just rock up to a space and plug it in and suddenly you'd have a seven-metre inflatable that sort of had the same monumental presence as a bronze.

TMWhat were they made from?

CRIt was literally the same nylon that is used for shower curtains. I worked with an industrial fabricator on that, because when you plug one of those things in, they kind of flick around. I did that in my studio and it wiped everything out!

With Transmutation, it began with the same process of creating form from canvas, but this time, instead of the volume coming from air, it came from casting solids. So the bronzes, like many of my sculptures, have this soft sculptural sensibility, even though they've shifted into the hard form of the monument.

The subject matter related to my ongoing interest in interconnectedness. I wanted to tie the human into the natural world. I had been exploring that through museum specimens and disappearing species and it was important that the figure was part of nature, not above it. So I looked a lot at Andreas Vesalius' language of anatomy and by revealing the skeletal structure, I de-gendered the figure.

Transmutation was the first time I ever used that cartouche form. I used it as an empty frame where the head would be, and I liked the idea that it was inviting you to look into this vacant space where the face should be. There is a bird of prey sitting on top of it looking down.

TMWith your botanical works, the history of colonisation is described through processes of collecting and controlling, but they also open up a new celebratory narrative of nature. How do you choose the specific plants that you focus on? And do they perhaps act as a mapping tool for you, having moved between New York, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom?

CRI think that connection to plants is my way of trying to understand place. I do look a lot to plants as a way of talking about culture. It's also this question of what we consider to be weeds. A weed is just a plant that's out of place. I found a book in New Zealand years ago by F. W. Hilgendorf published in 1926, called The Weeds of New Zealand, and on the front cover is a silver fern, which is now the national icon.

I find plants are a useful way of talking about history, and the politics of place. And I think people are again realising that plants are life, from providing habitat, food, affecting weather patterns, releasing oxygen, storing carbon, and so on.

I'm often looking at plants or images of plants that have some reference in history. I've been interested in Joseph Banks' representations of plants from Kamay Botany Bay. The prints are stunningly beautiful and lovingly rendered and yet they also represent the moment the invasion of Australia began. The botanical specimens that are plucked, re-named, and claimed also come to represent that systematic colonising force.

I find plants are a useful way of talking about history, and the politics of place.

I like your idea of plants being a mapping tool. I've recently been researching the vast databanks of Kew Gardens and it got me thinking what a fascinating resource all that data is and how these sites of imperious collections now seem to be shifting from being vaults signifying power to informing people about ecology, biodiversity, regeneration, and readdressing monoculture.

Last year I took an idea to Google Creative Lab and it started as an interest in this kind of data, along with plant blindness—we all walk through the world saying, 'Oh isn't that beautiful, isn't that lovely!' But at the same time, we have very little knowledge and understanding of plant life.

My mum's side of the family were Irish street botanists, my father's side were industrial chemists, and I kept finding these museums of economic botany, which were a kind of collision of both, and I got thinking about how botany is so part of everything we make—fabrics, food, pharmaceuticals...

TMIt's become another vernacular.

CRYes, exactly. So I started thinking, what if I could create this app experience where you dive into data, and you get information about plants, but at the same time you get an artwork?

So I've been working on Infinite Herbarium with Google Creative Lab, which is a virtual experience where a participant will be able to photograph two plants, each will be classified, and then the information is fed back through data sets from the Biodiversity Heritage Library—an open source online library—and via a process of machine learning, a new hybrid plant is created out of the two plants. It's about building curiosity.

TMCuriosity so crucial to your works, because they deal with difficult realities, and bringing in this element of curiosity opens them up. Do you see your works as hopeful for the future?

CRCuriosity has a complicated history in the West, but I think it also has great potential to build connection.

For me, making art is a way to delve into all of these conversations. You mentioned geoengineering, which I was looking at during my 2014 show, Weather Maker, at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, which looked at emerging weather modification technology. Perhaps the next act of colonisation will be the atmosphere, and I think some of these geoengineering projects, if they get going, have the potential to create unintended consequences that will ripple well into the future.

We're living in high-speed history at the moment. It's so fast. And there are all these battles raging for control—for the weather, the atmosphere, for our ecosystems. And with industry, often it's the shareholders and quick profits that are at the centre, rather than the citizens and other species we share the planet with.

TMThere's no doubt that there is growing awareness in relation to the environment. All the same, technological developments continue. We are being catapulted into a new present, and it's hard to imagine what it will look like.

CRThe awareness is something to be hopeful for and I think with Covid-19, people have started listening to scientists. The other thing about this pandemic is that it is a zoonotic disease—it's the result of us having inflicted ourselves on the wilderness.

We have to build this idea that our connection with the natural world is a fundamental existential connection. I do feel a bit more hopeful. I look backwards to try to and make sense of the current moment. I look at the way ideas are portrayed, to get a sense of the ideologies of the moment we're in. —[O]