Jesse Darling: 'I have to believe in coalition and community, despite everything.'

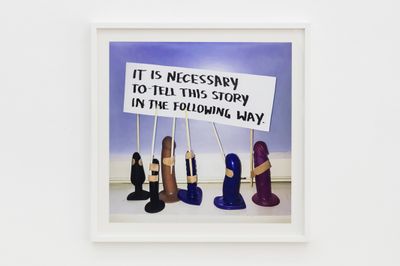

Jesse Darling. Courtesy the artist.

Jesse Darling. Courtesy the artist.

Over the last ten years, Jesse Darling has explored how systems of power—government, religion, ideology, empire, and technology—can be as fragile and contingent as mortal bodies.

Working across sculpture, installation, video, drawing, and text, his distinctive artworks expose the libidinality of social reproduction and expose contradictions within dominant narratives about the world, our bodies, and our lives.

Darling's work is comprised of everyday objects as well as the materials and technologies that produce and maintain the body and the border. Playing in the limen between stability and dysfunction, his work evokes counter-histories and speculative models to rethink the concept of resistance.

In his recent survey exhibition, No Medals No Ribbons at Modern Art Oxford (5 March–1 May 2022), Darling configured new and existing artworks into a symbolic landscape of recurring gestures and motifs, with sculptures as proxies for bodies and allegories.

Curated in dialogue with the artist, the exhibition charted how Darling merges lived experience with mythical symbols, religious fables, political thought, and pop-culture references to open new ways to think about the world. A common theme underpinning Darling's work is the idea that 'to be a body is to be inherently vulnerable'. In recent years, Darling has explored this notion by assembling his work around material forms of debility, where bent and curved works stand in for unruly bodies.

Despite their durability, Darling's artworks are often precariously assembled. Insistent that nothing should live forever, the artist imbues his sculptures with entropy—the tendency to collapse and break down over time. Crutches and walking aids prop up standing sculptures, while the legs of chairs and cabinets appear injured or wounded with kinks and bends.

Collectively, these works evoke the inevitability of the body's failure, and express a desire to resist social and political constraints imposed on life by an extractive system. They encourage us to think about vulnerability and interdependency as crucial aspects of our lives together—a proposition most recently addressed in Enclosures (13 May–26 June 2022) at Camden Art Centre, London.

There, Darling considered the broader social and psychological implications of enclosure, and the effects that increasingly privatised and individualistic thinking has had on Western systems of caregiving, architectures of domesticity, and perceptions of the self outside the commons.

Concrete pillars stand as ruined relics of crumbling empires. London bricks form a ruin or foundation restricting movement. Surveillance systems become panopticon in the farcical presence of detached governments, while ribboned hammers and weighted baby carriers speak to scripts of labour, gender, and identity.

Amongst it all, many hands in the continuously evolving installation, Light Work (2018–ongoing), allude to the messy and unfinished labour of coalition-building and collectivity. With an upcoming exhibition at Chapter NY in the fall of 2023, and works on view at Art Basel Miami, Jesse Darling and Modern Art Oxford curator Amy Budd discuss the contents, process, and messages behind the artist's work.

ABYour exhibition at Modern Art Oxford was the first survey of your work to date. It brought together new and existing sculptures, drawings, photographs, and installations made over the last ten years into thematic arrangements for the first time.

You chose the title No Medals No Ribbons, which indicates an act or gesture of refusal. Can you explain the meaning behind this phrase?

JDIn common terms, it's a kind of repudiation of the triumphant retrospective thing that goes along with a survey show. On the one hand, it's pretty much what it says on the tin. It's also a quieter reference to a distant ancestor of mine whose story I came across recently.

As a prisoner of war, he started bricolaging artificial legs for his injured comrades from pieces of window frames, metal chairs, cotton batting, rubber from old tires, camp scrap, and anything he could get, bribing the guards with chocolate and cigarettes for stove fuel.

According to vernacular reports, he made up to 300 artificial arms and legs, some of which had complicated jointing mechanisms. When the war ended, they sought him out for recognition and decoration but he refused, saying it was best to forget. His materials list looks a lot like mine although I'm not living through war or making anything useful in this sense. And sometimes, though I think a lot about history, I think I would rather forget my own.

ABThroughout your career, you have conjured sculptures and installations from a spectrum of everyday plastic debris, which often merges with austere steel and metal offcuts, and other bits of unwanted domestic ephemera.

It seems these incongruous materials hold the potential to symbolise complex ideas, as you've previously described steel as 'part of a history of the extraction and colonialism', while plastic is 'a synthetic technology of immortality'. How do you choose the materials you work with?

JDA lot of the time, I used what was cheap, or free and easy to find. There's poetry in objects everyone can recognise from their daily lives. It's a shortcut to meaning and affect, and I like the fact that the meaning ascribed to everyday objects is necessarily personal and individual, as well as social and defined by people's experience of use.

I've learned to trust that objects and materiality in themselves are sometimes smarter and more eloquent than I could ever be. I find myself drawn ambivalently to petrochemical materials—steel, plastic, silicone. I noticed that this was a consistent thread and did some reading around the histories of these materials, which gave me a lot to think about.

Plastic is a zombie medium—lurid and undead, made from fossil fuels, which are in turn made from the exhumed bodies of our ancestors. Steel is a technology of coloniality and capitalism, of war and industry. These materials have produced my body, in a manner of speaking, and everything I know. So, you could say that it's autobiographical, but my autobiography isn't just about me.

It's a story about the feudal church, the enclosures act, the industrial revolution, the British empire, the transatlantic slave trade, Henry Ford, Walt Disney, Margaret Thatcher, Tony Blair, Hitchcock, NASA, Nickelodeon, World Wars One and Two, the welfare state and its dissolution, mining and the miners' strikes, the failed sexual revolution, Silicon Valley, 9/11 and the wars in its wake, penicillin and the pill, the DSM and AIDS, and Covid-19. It's much bigger than I am.

ABI'm curious about how you develop your ideas. You seem to have an autodidactic approach to art-making and storytelling. What is your starting point?

JDI don't know what autodidactic means, but I feel like I had to figure out my own approach to working out the things I wanted to say, or the things that wanted to be said through me, despite me—although every artist has to do that.

I guess my ideas come from the same place as anyone else's: my upbringing, education, position as subject (age, race, class, gender), whatever's been going on in my life or in the news at any time during my years as a person in the world, the collective unconscious, and messages from the ineffable.

I start with intuition and muddled feelings without form, which find shape through the process. Often, I'm not sure what I've made until afterwards, and then sometimes I'm shocked or disappointed. I say I'm not a conceptual artist, just an artist who thinks and sometimes reads a lot. But whatever drives my work, I can't get that from reading a book.

ABYour work often addresses the fragility and impermanence of life. This has been eloquently explored through your series of mobility aid sculptures evoking the physical vulnerability of the body, as with the crawling canes in the Modern Art Oxford exhibition. Other works, such as the decaying floral vanitas Still life (2019–2022) and crumbling plaster asthma inhalers, Peak Flow (2013–2022), also collapse and break down over time.

Mortality is an important theme for you, but is there also a hopeful message in your work? Could vulnerability also be a strength, and adaptation, resilience, and change be empowering?

JDFor me, it's quite a hopeful feeling to know that even empires fall, kings topple, and governments are overthrown. To know that everything has its end, even when it seems like the reign will be endless. Vulnerability is a given in everybody. It's what makes us alive. It's not that vulnerability is a strength per se, but our physical fragility as organisms and propensity to suffer in love, conflict, under structural violence, and our animal need for nourishment and warmth are what we share.

I am interested in man-made materials and by-products because they are expressions of will upon the world.

Although universalism is such a melancholic white-European Christian thing, I'm attached to it because I have to believe in coalition and community, despite everything. To acknowledge our common vulnerability at the level of the mortal body is a way for me to think about trying to care for each other.

ABYour recent commission Enclosures at Camden Art Centre coincided with the Modern Art Oxford survey exhibition and seemed to signal a shift in direction. The work, resulting from the Freelands Lomax Ceramics Fellowship, focuses entirely on clay, which has previously appeared in your sculptures and installations, but only in its unfired form. What was the starting point for this new body of work?

JDI wouldn't say it's entirely focused on clay, but because I wasn't going to be anywhere near Camden for the duration of the fellowship, I took up the idea of clay as something indigenous to the ground and the land—something dug up and put to use.

When you think about the ground, you arrive at the idea of land, and then borders, because that's how nation-states propose and enforce themselves, with rhetoric pinned along the borderline. Then, you arrive at the limen, and whatever lies beyond the border in every direction.

Everyone knows about the things that borders refuse or seek to erase—lives, ideas, ways of living—but there are also plenty of things it cannot contain. I am interested in man-made materials and by-products because they are expressions of will upon the world, like art, or anything we make.

So there was a lot of concrete and brick in the show to represent architecture—the ground above the ground. I also used different clays, which look, work, and signify different things. I wanted to evoke a preciousness—both as something special, beloved, and vulnerable, and as weaponised or permitted [white] fragility. For this, I used porcelain.

Elsewhere, unfired clay stands in for what is messy and unfinished; a rough-fired earthenware contrasts architectural materials as the fluidity of living does the rigidity of the enclosure. Not that this was conscious exactly, but now that some time has passed, I can see it more clearly.

ABThis commission directly addressed the current political climate in the U.K., perhaps more explicitly than previous artworks and installations: closed-circuit cameras evoke the prevalent surveillance and policing of society, and the gallery is demarcated with bricks, fences, and barbed wire to suggest the aggressive privatisation of space.

Heaps of headless porcelain dolls are vulnerable discarded subjects that could represent the dismantling of a welfare state. But the installation also takes a long view and can be read as a post-mortem enquiry into the origins of 'enclosures', questioning why the primacy of land ownership is so entrenched in the British psyche.

How did you develop this work remotely from your current residence in Berlin? When thinking through these questions and histories, does it help to have some objective distance from the U.K.?

JDI am able think and work because I live somewhere with a welfare state. There is also some kind of precedent of 'the commons' here, or just civic space, which is also a complicated paradigm I don't want to celebrate unequivocally, though it throws some light on the situation in the U.K. I doubt that my distance is in any way objective. I am consistently appalled by the headlines in the U.K. and the reporting in general.

I'm not sure if the shock is valid as data, but I'm equally unsure if the national prerogative to keep calm and carry on is a proportionate or appropriate reaction. I have a U.K. passport and have spent about half of my life living there, so I wouldn't claim to be a neutral observer.

The enclosure is not just a British paradigm, after all. It's the story of the larger European project and every colonial initiative. So it's not like there's really an 'outside' anywhere I go, not least because I am part of it, and/or it's a part of me.

ABIt's interesting to see CCTV surveillance cameras used in the installation. Did this occur to you during installation, or was this something you already had in mind?

It's tempting to connect these interventions with your earlier digital practice, but your use of the screen here is more voyeuristic. It reminds me of 1970s closed-circuit video practices, which made visitors unwitting performers for the camera.

JDIn my long-ago digital practice, I was riffing around the conditions of visuality and labour, the poetics and politics of the scroll and feed. These bodies of work are distantly related, though I'm more interested in historical materialism than in hyper-contemporary virtuality nowadays.

There are three different cameras in the show: an old-style CCTV camera, a small spycam for home use, and a baby monitor. It's very Panopticon 101—a little comment on the continual feed and capture, how normalised this has become, and the affects it produces.

In the contemporary paradigm, surveillance tends to get folded in with care and protection, which we all know. But it rarely seems to be problematised, even as we rehearse these concepts of informed consent and cultural property ad nauseam, while hearting viral videos of somebody's drugged-up child crying in confusion after surgery and sharing cellphone footage in which someone is stripped and beaten by racist police.

The idea that CCTV will keep us safe is equally ridiculous—and dangerous—as the promise that media representation will improve material conditions and make us free. In fitting large areas of a city with CCTV, the municipality and government admit that most of the city functions as private property, even though this private property is for public use and thoroughfare.

I'm also interested in the vernacular use of closed-circuit cameras in the home, as the threshold of the private home in a certain context represents an extension of the border. As always, the underlying question is not so much what is being protected as whom it is being protected against.

Buying in to the idea of protection in appropriating technologies of state security, and/or assuaging oneself in the event of state law enforcement, the private homeowner becomes a protectorate of the landowning feudal state. This buy-in clause is not available to every private homeowner, of course, which exposes the lie of liberal democracy.

ABWhen we first spoke about your work on Zoom, and ahead of inviting you to present an exhibition at Modern Art Oxford, you mentioned you were thinking about sleigh bells. I was very surprised and intrigued to see silver bells attached to hammers in the cabinets at Camden.

Do you tend to think about an object or material for a while before you know what to do with it?

JDYes, sometimes I'm drawn to something and will seek it out in the studio without a clear idea of what it needs to do or where it'll end up. I've learned not to question this impulse too much, nor analyse the object or material too deeply, but to trust the haptic poetry of a thing.

I will look at or handle it for a while without trying to understand it. Sometimes I'll dream about it, or wake up suddenly at four in the morning with a clear sense of what the thing wants to do. Only afterwards do I think about what it is that I've made.

ABIt's hard to get away from history in your work. It informs both the narratives you excavate and how you repurpose modes of museum display to reconfigure knowledge production and ideas of the past.

For instance, the floor-based installation of London bricks, Enclosures, recalls an archaeological dig. Seeing these bare-bone foundations across the room reminded me of the snaking structure of Gravity Road (2020), installed at Modern Art Oxford like a prehistoric dinosaur skeleton. Are you particularly drawn to evoking or critiquing the museological aura of artefacts? What does a relic or ruin mean to you?

JDEvery artist working in the Western context works in the museological afterlife with all that this implies: imperial violence, appropriation and deterritorialisation, specific rituals and systems for taxonomising objects, and data taken to be universal. All these aesthetic and epistemological legacies are themselves part of the afterlife of the Christian church.

I'm uncomfortable with work that doesn't seem to know or acknowledge itself as such, or work made for circulation in the Western context that imagines itself to fully transcend this. The relic and the ruin are what we're currently living in, especially in the dead world of contemporary art. —[O]