Mahmoud Khaled Queers the House Museum

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE MOSAIC ROOMS

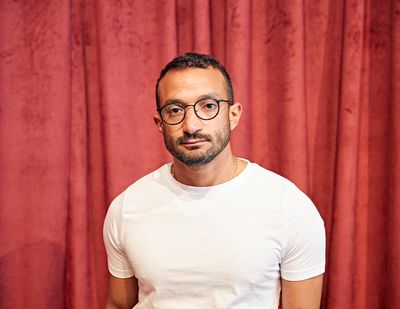

Mahmoud Khaled. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andy Stagg.

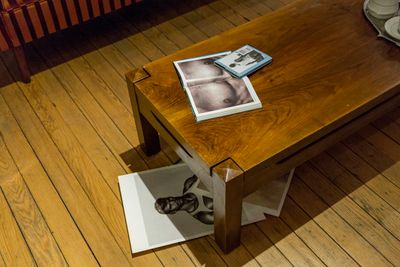

Mahmoud Khaled. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andy Stagg.

Berlin-based artist Mahmoud Khaled has thought about the interiority of spaces and how they function in relation to our bodies since he began making art.

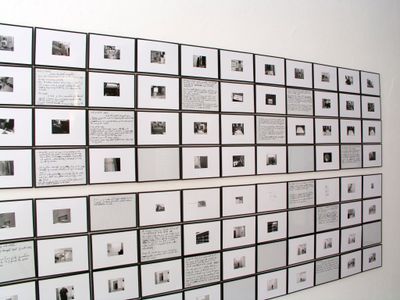

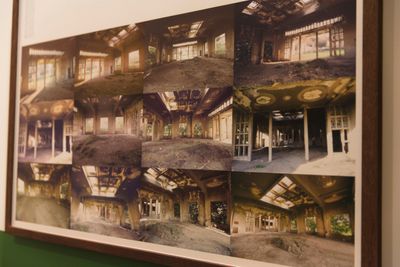

Back in 2006, you could find works that reference this, such as My House is My Studio and My Studio is My House, a wall installation of black-and-white images depicting spaces that double as the artist's home and studio framed alongside fragments of handwritten text.

Made the same year, 15 Minutes of Acting as if I'm in my House comprised 190 stills from a 15-minute film of the artist cleaning up a run-down house in Aley, Lebanon to restore the private identity of the now-public space, partially destroyed during the civil war.

Having lived in interior spaces during the last years of the global pandemic, it has become ever more prescient to think about the latent histories within the fabric of our cities, the texture of the spaces we occupy, and how they can become sites for possible imagination.

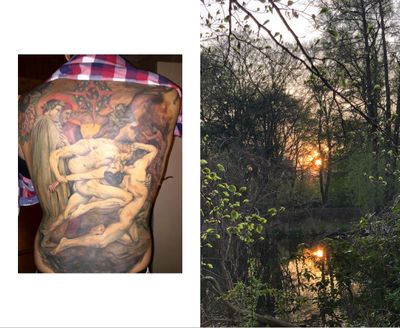

Accordingly, Khaled's first U.K. solo exhibition at The Mosaic Rooms in London, Fantasies on a Found Phone, Dedicated to the Man Who Lost it (22 June–25 September 2022), re-orients the format of the house museum towards marginalised queer life by positing a mysterious fictional owner.

Starting with an unlocked phone without a sim card inside a men's public toilet, the artist has ambitiously used The Mosaic Rooms' architecture as a setting to render a portrait of this elusive owner—'an erotic, elegant, but troubled man, suffering from severe insomnia and loneliness, dependent on sleep-aid and dating apps.'

The artist has imagined distinct domestic environments, including two installations Calm and For Those Who Can Not Sleep (both 2022), using sleeplessness as a metaphor for political states of being, not belonging, and being displaced.

Calm is a sparsely furnished room with extravagant detailing-red velvet curtains encasing the walls, and a daybed of exaggerated proportions composed of leather and wood. The space is proposed for reading, reverie, and according to the echoing soundtrack, for lustful activities.

Visitors are invited into a meditative exercise lead by the soundtrack, which creates a powerful and affective environment guided by a semi-automated voice of an absent figure, sited in the room before parallel murals depicting a scene of nighttime despair.

For Those Who Can Not Sleep is a dimly lit room animated by a circular bed in perpetual motion and scored by a discordant soundtrack. Moving at an almost unnervingly slow pace, the leather strap acts as a measure keeping score of the melancholy and disquiet.

The exhibition sets a stage for visitors, as voyeurs, to seek out the artist's carefully curated clues. By re-orienting the format of the house museum, it creates a space for self-reflection and critique of devices and spaces that supposedly offer points of interaction, reflection, and solutions to contemporary life.

Mahmoud Khaled's practice is both process-oriented and multidisciplinary—a space for critical reflection that can be regarded as formal and philosophical ruminations on art as a form of political activism. Below he speaks to author and curator Omar Kholeif about this new body of work and his wider practice.

OKIn the introductory text you authored, you mention that there is a sense of a displaced viewer. As you enter the space, how do you imagine the viewer's gaze? Where is it that you want to take us with this house museum?

MKFor me, solo shows are always a great chance to design an experience for viewers. It's not that I'm showing them something, but rather I am in full control of designing everything.

The moment you cross the street, you see yourself in the mirror with the title of the show that invites you to take a selfie before entering the space. I didn't want to transform the space into a house museum, which I had done before as an imagined institution, but to use the house museum as a medium and a device.

The Mosaic Rooms has a history as an exhibition space and building. I wanted to work with that. So the work plays with the idea of the house museum, with all the things I learned from visiting other house museums and reading about them and the strong curatorial voice they have.

You can't deal with the gallery space as a white cube or a neutral space because it has a loaded history and identity.

The voice of the narrator is very important. I paid particular attention to the relationship between curatorial work and the narration—the framework, story, and associations you make as a curator. And I do play this somewhat curatorial role in my work.

The show imagines a protagonist, which is an exercise we all do when we visit house museums. There is always a strong sense of absence and delay in those museums and our relationships with them. We're always too late: we go after the person who used to be there is gone. I wanted to recreate this moment.

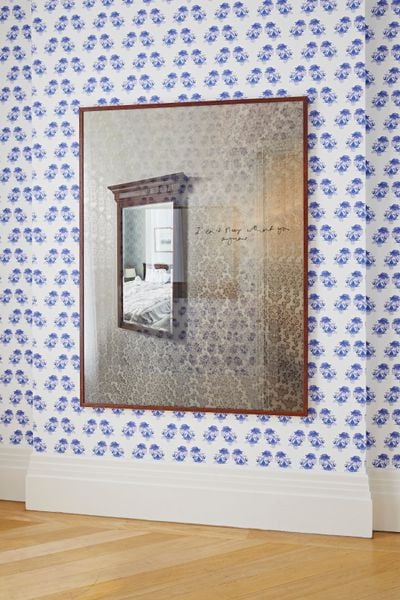

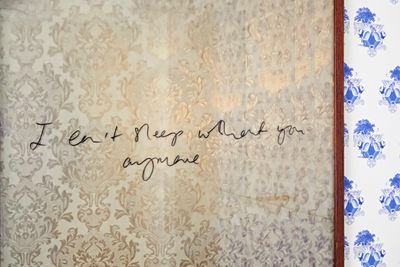

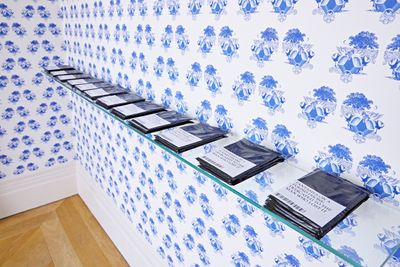

The exhibition starts in the landing room. Normally in museums, the landing room has an exhibition or wall text that gives you the key to how the exhibition is experienced and curated.

Here, the exhibition text is transformed into an artwork with a note and a mirror, the wallpaper is inspired by wallpapers that I have seen in London when I came for my research and looked at Victorian house museums, such as Charles Dickens Museum.

We can see samples from these wallpapers in the Victoria and Albert Museum. I wanted to have them in the show but in a design that is not so expected. For this, I would like to thank the graphic designer Engy Aly with whom I collaborated to design the wallpaper.

OKFrom the poster outside to the lead-up inside, there is a constant reflection of, or an act of fragmentation. Even taking pictures for Instagram in the exhibit yesterday, I could see myself reflected across surfaces. Before you enter, you may assume that this house museum belongs to the dead.

Whose phone did you find? Or would you rather we contemplate our own gaze rather than theirs?

MKThis was in dialogue with the exhibition space and the architecture. It's a very inspiring space, but it's also very difficult to work with. You can't deal with the gallery space as a white cube or a neutral space because it has a loaded history and identity. That's why I imagined making a portrait of a protagonist.

I thought of staging a domestic environment that could be owned by this person. I was given three rooms to finish the sentence that I wanted to make into an exhibition. The two big rooms are quite identical in size, but different in feeling and atmosphere.

The first room on the ground floor used to be the grand salon of the house, where a rich person puts their wealth, antiques, and art collection, to perform their legacy, power, and taste.

OKIs that why in the centre of the room, there is this B.D.S.M. chaise longue that resembles an endless phallus? It is so untouchable, almost as if you took the antiques from the walls and put them there.

MKYeah, the original photos from the house were so maximalist and intense—with too much stuff, like the storage of a museum. You could tell that the person was super rich. I wanted to be very minimal, more subtle—to play with gestures, but also with emptiness, absence, and delay.

OKThrough absence and delay, you link to the concept of anxiety, which you mentioned as being something you want to elicit within the space. Could you speak of the sound piece you've created in the first room as an invitation to rest?

MKIt's an imagined podcast from a sleeping app—something between Alexa, Siri, and a person.

The idea of a successfully written sleep podcast is that you don't finish it. The one in the exhibition suggests that the protagonist is trying to use the room as a sleeping room but it's not a sleeping room and that's what the app is trying to tell you.

I imagined an app that is quite advanced in the way it tracks your memories, feelings, and location, and can tell you where to be based on what you want. By tracking your memories, the app can remind you of all the things that cause your anxiety and panic attacks and then asks you to remove them from your system. Like a one-to-one live-coaching session based on a subscription.

There is also a strong sense of beauty that I tried to keep in the room, with the arches, the murals, and the design of the daybed, which has this kind of fetish and kink aspect to it. I don't call it a B.D.S.M. object, but it can be interpreted as a phallic object.

OKThat is interesting because yesterday you referenced a kink museum in Chicago, in Rogers Park, that you visited during your residency at the Hyde Park Art Center.

You've mentioned that for the curators who work at this museum, these materials that are used in B.D.S.M. activity were presented for their aesthetic sensibility in a very formal design setting. Was this influential in some of your thinking?

MKAbsolutely. It's very important, this example of the leather archives and museum in Chicago. The way that the institution and collection are built, the way people working in this archive speak about their work, and their mission statement are very influential to me.

It's an archive of desire, in a way—a document of the fetish scene in Chicago in the early 1980s and 90s. Most members of the fetish scene there died of H.I.V. Their families didn't know what to do with the things they left behind (fetish objects, costumes, so on), so a foundation was made to keep and collect this history.

The collection captures stories, kink furniture, objects, clothes, magazines, and letters, among other things. This organic format of archive building tells us a lot about what was happening in Chicago at the time.

There's a lot about a certain history of desire that is not normative. We wouldn't be able to know without this kind of institution, which makes me question: How can we write a history that is always forced to be intangible?

OKYou mention the word normative, which speaks of the presentation of desire as a manifestation of what is now articulated as a queer desire, sensibility, or aesthetic.

When we had our interview in that house museum in the basement of the Delfina Foundation in 2012, the word queer wasn't appropriate to use because we had not reclaimed it as a community. Could you reflect on that shift and how that presents itself in the work here and beyond, if at all?

MKWhen I started working, the word queer wasn't part of my vocabulary. It wasn't part of the common dictionary in the art world, and that of curators and writers I was working with. With new generations of writers, curators, and artists, there's an establishment of this definition that I am still trying to understand every day.

I'm also learning from it every day, as it isn't an identity I relate to. There are different ways to deal with non-normative ways of experiencing love and sexuality and it's interesting to think about how things change, and how we speak about our idealism, feelings, desires, work, and how that shifts as well.

OKSince that time ten years ago, there was this period of unlearning certain tropes and languages—of constantly having to refer to our work as being in a 'post-colonial' context or being 'against something'. The term 'post' was put in front of a lot of things, such as post-internet.

Do you feel that we've stripped back to an ability to create our own visuality and sensibility that's cleverer, and more culturally and racially situated?

MKI'm very aware of what you're talking about. It's not inspiring for me to be against something in the work. From my position as an artist, it's not what I feel like I want to do anymore.

Now, I'm actually enjoying the role of imagining, proposing, staging, fictionalising, and fantasising in my work.

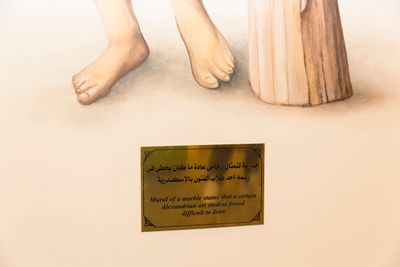

There was a moment in my work where I was against things, I was against maybe a certain art education that I learned in Alexandria and I made several works that reacted to this specific form of education. But after working and maturing, you realise that it's not enough.

Of course, politically, there was a moment when I felt that the work should be about statements. Now, I'm actually enjoying the role of imagining, proposing, staging, fictionalising, and fantasising in my work. It's more inspiring and keeps me going.

As an artist, it makes me feel that I can work more and that I still have something to say to the world, instead of just making a statement and leaving. The word proposal is often at the beginning of the titles of my works, which gives me a certain freedom to think and shape the work.

For example, the Unknown Crying Man Museum is titled Proposal for an Unknown Crying Man Museum (2017). It's a memorial that is very important to me politically, but without the word proposal at the beginning of the title, I wouldn't be so comfortable.

If I'm commissioned to make an actual memorial for the event, I wouldn't be that free in my thinking. It took me some time to understand the position I want to speak from as an artist.

OKWhat's beautiful about this proposition, as you mention, is an emerging constellation of proposals. First, with the work Painter on a Study Trip, which has surprising facets to it, like the anecdote you told me of a proposition for a queer Alexandria, housing the Arab League meetings. Would you mind sharing?

MKI realised Painter on a Study Trip in 2014. It started as a way of thinking about my own experience in a classic fine art school in Alexandria, and what kind of artist I was supposed to be after.

The point of departure for the work is a park in Alexandria called Antoniadis. It's a small villa with a big garden once owned by a very wealthy man, Sir John Antoniadis, when Egypt was still a monarchy under King Farouk.

King Farouk was invited to a party at the house of Sir Antoniadis, and he was so amazed by how beautiful the garden and the villa were that he got a bit jealous, and told the sir: 'This is not okay to know that you have a better house than mine.' Sir Antoniadis was so polite and told him: 'Everything in your kingdom is yours.'

King Farouk took the kind offer seriously and took the house. Later on, there was an agreement between Sir Antoniadis and King Farouk that he should give the house to the city of Alexandria, but it has to be kept under his name. Then, it became public property under Gamal Abdel Nasser.

A lot of important things happened with this house; it's where the first meeting of the Arab League took place. Over the years, our political leaders changed in Egypt. Suzanne Mubarak wanted to make into a library connected to the library of Alexandria, but for kids.

The garden was like a miniature version of the Versailles gardens in France. It was a very important site for art students, and up until now, I think the fine art school in Alexandria sends their students to paint in this garden, to make assignments based on the landscape because they think that it makes them better artists.

All these interests around the house and the garden became a site for producing artists from the city. Of course, the public park was also a place for lovers; many intimate and erotic things were happening there, and people were taking drugs.

This was a while before I started thinking about the house museum as a construct. After some research and experience with house museums around the world, I've noticed they are mainly made for straight men. It's very rare to find a house museum for a queer person, woman, refugee, or someone unknown.

I wanted to imagine if the first meeting of the Arab League would have happened there if there was somehow a queer reputation around Sir Antoniadis, whose name was kept for years. These things are interesting for me to question and the legacies around that history.

OKI think the connection towards these spaces has been ongoing in terms of your exploration of interior setups in your work.

Yesterday, you gave me two books. One is wrapped in plastic, could you open it and tell us what it is about? Tell us something about this plastic wrapper.

MKFor the plastic bag, I have to credit Marwan Kaabour, who is the designer I worked with on the book. It was a great collaboration.

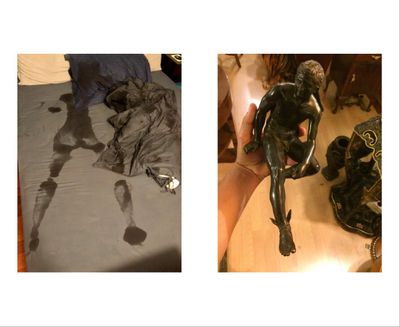

The phone is the main protagonist of the work and it has content. The book is the only way to access the content and Marwan did a great job curating the content of that phone in this publication.

OKThere was another book that you recommended to me last night. Can you tell us what this book is?

MKThis book is a novel called Against Nature [1884]. It's very specific and the nature of the protagonist is somehow what I find in my work subconsciously, all the time. This person is well off, there are a lot of class connotations in it that we cannot avoid.

In the House Museum of an Unknown Crying Man, we're talking about a person who could afford to live in such houses with taste and style, and to buy art to stage his own world. This is a privilege I wish all of us could have. In reality, it's only accessible to a certain class, and there's no way to get rid of that.

This book talks about a man who staged the whole world in his house. He has a room called London and a room called Paris and every time he wants to travel, he doesn't—he has it there. This caught my imagination. Two days ago, I visited The Cosmic House in London, and funnily the owner of the house had a room for Egypt. So apparently, it's a ritual for rich eccentric men.

Interestingly, all the house museums I visited are very asexual. A very good example of this is a house museum of Constantine Cavafy in Alexandria, who is a great poet. I used to go there when I was a little kid and loved the apartment and the guard.

They never talk about his sexuality, as if he didn't have one. They just say that he's a lonely, wealthy man writing poems in cosmopolitan Alexandria. And for me, this is an ongoing question. The same happened in the Charles Dickens Museum, which I encourage everyone to go see.

There were hints about the sexual relationship between him and his wife's sister, but they didn't want to be judgmental and unfold it. But houses are also places where sexuality is being performed and celebrated. The moment a house becomes an exhibition, sexuality gets removed.

Someone else decides to make the museum for you and there's a class judgement in the process.

I wanted to ask about this in the work, in the design of furniture and the environment that I was trying to create. There's class and inheritance, but there's also a lot of power behind house museums; you cannot make a house museum for yourself, you always have to disappear.

Someone else decides to make the museum for you and there's a class judgement in the process. For example, Sayed Darwish, the musician who composed the national anthem of Egypt, deserves a house museum. I'm from Alexandria, the city where he was born, lived, and worked.

His house was in a poor working-class area but in very good shape. It just needs to have a sign on it and a board of trustees. But the state decided not to do that because it's a very working-class neighbourhood and doesn't attract that much attention.

OKYour work seems to be deeply rooted in creating monuments or anti-monuments for people who are dispossessed from being able to articulate an identity, or have been in a partnership in a certain way.

MKI think the works I'm making try to imagine this possibility. But after listening to your comment, it's also important to admit that the works also follow this class standard. One cannot imagine a working class queer person, who is barely living on his salary, doing two jobs to design a daybed so long and expensive to enjoy, and making a mural that celebrates anxiety.

There is a sense of leisure. Unfortunately, it comes with the format of a house museum. I would like to shift it a bit from the class struggle but it's there in the form.

There's also a lot of power around who decides to keep a certain archive and destroy others. We now have growing archives in our hands: mobile phones. And that's why the phone is very important in this show. Based on what we see in the phone as an archive, we can imagine the protagonist, or try to as viewers or voyeurs.