Lauren Halsey: Centring Community

Lauren Halsey. Courtesy the artist and David Kordansky Gallery. Photo: Czariah Smith.

Lauren Halsey. Courtesy the artist and David Kordansky Gallery. Photo: Czariah Smith.

Originally trained as an architect, Angeleno artist Lauren Halsey has developed unique spatial paradigms for South-Central Los Angeles (also known as South L.A.), which reference funk, hip hop, Afrofuturism, and science fiction.

Bringing community engagement in dialogue with art and architecture, Halsey counters present-future uncertainty with optimism for the neighbourhood she has lived in since childhood. The artist's speculative, immersive installations and proposals for community spaces adopt a radical architecture, echoing Tina Campt's call for a Black futurity as 'an attachment to a belief in what should be true, which impels us to realize that aspiration.' 1

Describing herself as a 'fantasy architect', Halsey is deeply invested in re-imagining South L.A.—encompassing Central Avenue, Watts, and the Crenshaw District—as a thriving and sustainable Black community for future generations. Her family settled in the area during the Great Migration of the 1920s,2 when many African Americans migrated from the rural South to urban areas in the Northeast, Midwest, and West for economic opportunities. Generations of Halsey's family have witnessed the area's many transformations, including the growth of a celebrated jazz era and district in the 1920s. Turbulent times followed, with the infamous Watts Riots of 1965. Today, gentrification threatens to displace local communities.

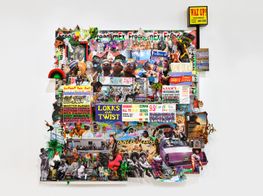

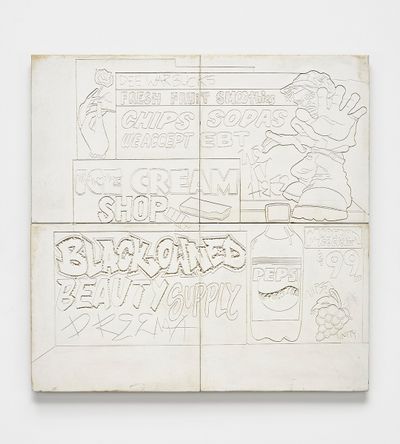

A collaborative ethos is critical to Halsey's practice and was evident in The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project (Prototype Architecture) (2018), presented at the fourth iteration of the Hammer Museum's biennial exhibition, Made in L.A. 2018 (3 June–2 September 2018). The project consisted of a prototype for a future public space on Crenshaw Boulevard, in which Egyptian hieroglyphic writing was reinterpreted with contemporary imagery characteristic of South L.A., including local storefront signage, portraits of family and friends, low-riders, tags, and local landmarks.

In 2019, Halsey extended her collaborative efforts to establishing Summaeverythang—a community centre that distributes fresh organic produce, free of charge, to neighbourhood residents as a response to the local effects of the Covid-19 pandemic.

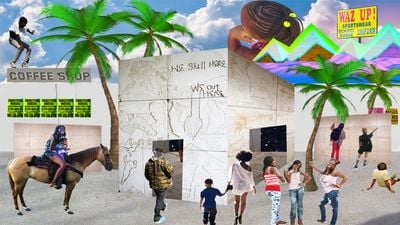

For her solo exhibition, we still here, there presented by The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA) (4 March–3 September 2018), Halsey presented a site-specific installation of cave-like structures bathed in cerulean, emerald, magenta, and violet lights, which housed a plethora of potted plants, reflective pools, and found objects that Halsey had collected from her neighbourhood over the years, including figurines, signage, and incense.

Drawing from a range of influences, from Chinese-Buddhist caves to the music of Parliament/Funkadelic, the artist presents a world celebratory of African-American culture that looks towards a brighter future.

Halsey's efforts mirror similar initiatives by a generation of artists invested in rebuilding their neighbourhoods, including Mark Bradford (another South L.A. native), who works with the non-profit Art + Practice to provide foster youth with support and free access to exhibitions. Meanwhile, in South Side Chicago, Theaster Gates' Rebuild Foundation focuses on supporting Black communities through neighbourhood relief initiatives. These artists' socially engaged practices are committed to reversing systematic racism in various capitalist systems that continue to shut out Black people from access to fairer banking, affordable housing, and healthcare.

In this conversation, Halsey talks about her love for South L.A., funk-as-architecture, putting the community at the front and centre of her art practice, and reimagining a future of Black greatness and generational prosperity.

JDHow did growing up in South L.A., engaging with its architecture, spaces, and histories of place-making, inform your vision to create multi-use architectural structures that place community front and centre?

LHI knew intuitively, pretty early on, that I wanted this process of creating multi-use architectural structures to happen with friends, family, and with people from the neighbourhood, so this became a part of the ethos very early on. If I was going to build spaces representative of the neighbourhood, it was important that I was going to include folks who were already aesthetically and spiritually invested in the process, so the structures and spaces would form part of a much larger statement. This was the beginning of The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project (Prototype Architecture).

I'm most excited to imagine a future for South-Central L.A. where we are not always under attack, whatever that violence may be, whether it's gentrification or other oppressive systems.

I'm working—slowly—towards building a series of hieroglyphic architectural structures that would resonate with communities here, so that when they see these structures aesthetically and symbolically, they would make sense to them. I don't want these structures to, you know, seem as if they were just imported into the neighbourhood. These buildings are informed by the sourcing and archiving of material that is culture-specific to South L.A.

Who gets to carve these hieroglyph structures? Who are the docents that will be in the space? All of these structures will come from a process of working grassroots with the community, so that people are able to see themselves represented in an architecture built by them and dedicated to them.

I haven't seen this kind of architecture in my neighbourhood yet. Outside community centres, homes, those kinds of spaces, I want to see spaces that can adjust to pluralities of programming, so that everyone—from young children to elders who have been here for generations—can coexist and contribute.

JDCould you describe how you've adapted the vernacular of hieroglyphs from ancient Egyptian culture for the present with The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project (Prototype Architecture)?

LHHieroglyphs have always been in the background and sometimes the forefront of my life. They've come up in music, images, and in the form of sculptures kept in people's homes. I also came across them in books at home that my father was reading. Hieroglyphs allude to a form of imagining, time travel, mythmaking, and fantasising around the origins of Black diasporic folk, as so many of us African Americans don't know where our specific origins are on the African continent.

What we do know is that we arrived in America from the continent as far back as 400 years. I am well aware that we weren't all kings, queens, and pharaohs [laughs], but very early on, I was compelled and obsessed with why someone would need to keep this symbolism in both their heart and headspace as a reminder to thrive in the contemporary moment, no matter what America says about them.

Right now, in this present moment of upheaval and racial injustices, a Black person can transport themselves in their minds to light years away or back to Ancient Egypt, to a time of greatness. I grew up with these kinds of ideas and began to notice that this also resonated with Black people in other places I had lived. For example, when I moved to Harlem for the Studio Museum artist-in-residence between 2014 and 2015, I got to know a few idiosyncratic groups that were also taking these mythical tropes from Ancient Egypt and transforming them into tangible sculptures and attitudes that they would act out and embody themselves.

JDCould you describe the make-up of geological modules, known as 'funk mounds', that recur in installations, including Too Blessed 2 be Stressed! (2019), presented for Open Space #5 at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris (4 May–2 September 2019) and your presentation at MOCA, we still here, there (2018)?

LHThe funk mounds are really about forms within the forms, and spatial possibilities. I view all of the work that I've made so far as experimental models that reference existing architecture. The funk mounds I created at MOCA and the cavernous forms for the Fondation Louis Vuitton speak to an experiment in building worlds underneath the ground. I hope to build an actual underground structure one day. This is a huge dream of mine—to create caves that become archives holding relics of South-Central L.A. culture.

As soon as I joined David Kordansky Gallery, I was pretty clear about certain works being made available only to Black collectors, and they were totally down with that.

I am representing my community through immersive architectural forms. The installations also display items I obsessively collect every day, whether that's incense and oils people in the neighbourhood are selling, signage, menus, CDs, and so on. I take this very seriously, and I see the funk mound as a form to house these things I collect without me manipulating them. They are more like archives created through the juxtaposition of everyday objects intrinsic to South-Central L.A.

JDThis obsessive collecting of South-Central L.A. material and visual culture—would you say there is an urgency to preserve what's being lost due to gentrification and a changing neighbourhood?

LHYes, it's more like a living and continuous living archive representative of my community, which I feel is urgent to preserve South-Central L.A. is not dissimilar to a lot of neighbourhoods elsewhere, that are gentrifying rapidly and disappearing, resulting in displaced communities. This isn't all over L.A.—it is happening to the most fragile and most vulnerable communities. There is a need for me to archive all of this, and it's something I've been doing since 2005—avidly collecting these things.

My collecting is similar to the way people collect baseball cards, coins, model trains, or whatever. I collect objects—including posters, mix CDs, and figurines—from a place of love and pride of this neighbourhood because I can assume, within the next ten, or maybe even five years with all these new infrastructures, all these people will be gone too.

I collect all of these things intuitively and I have done this for a while. The funk mounds are just one expression, as are the caves. I have all of these archives that represent a community being erased, so I do think a lot about placemaking of the archive and the strategies for what this might become. I have all this stuff, and I think of how it can become a tangible collection of things.

JDHow might these living archives and proposed architectural structures contribute to futurity that re-imagines South-Central L.A.? Is this something you are thinking of as a contribution to Black futurity?

LHThat's a big question to answer, but I do take each day at a time. I'm really interested in creating community ownership in the neighbourhood, and I'm most excited to imagine a future for South-Central L.A. where we are not always under attack, whatever that violence may be, whether it's gentrification or other oppressive systems. We need to have neighbourhoods here that Black people control and run for and by ourselves.

There's no way in the world I could separate the subject, the people, the community, and the context from the reward of the work.

As far as resources are concerned, the emphasis doesn't need to always be seeking out access to capital outside, as resources are already here within the community. We need to think in terms of FUBU—For Us, By Us—and have, for example, our own community gardens that are thriving and produce food, so there's not a dependence on grocery stores with produce that's filled with chemicals and not good for us.

This also means extending to initiatives that mean we run our own archives, libraries, schools, and run Black-owned businesses. So, I imagine a future that isn't so dependent on the capitalist state or other forces in order to survive.

JDSummaeverythang was established in 2019 with a mission for 'the empowerment and transcendence of black and brown folks socio-politically and economically, intellectually and artistically.' How has the Covid-19 pandemic shifted the way you've operated?

LHI never imagined that the community centre would be producing and distributing 600 produce boxes a week for the neighbourhood for free. Managing a food assembly every Thursday has become my whole life. Before the pandemic, I had no clue that I'd be working in this way. We had planned to work on the garden, with children and young adults taking advantage of the space, and to roll out a programme of tutoring in the summer and fall.

What's been so amazing about having my own space is that it is flexible and responsive to what the needs of the communities are at a given time. So that what's been happening with the produce box distribution, every week for the past ten weeks.

Before Covid-19, the South-Central area was already neglected. Back in March, with approximately 40 percent of low-income folks losing their jobs and not having access to resources and capital, it made the most sense to sort of slow down the artmaking and focus on providing for the community.

When all this started, I thought I'd just go on an art vacation in my studio and experiment with textures and forms, but it quickly felt irresponsible to focus on making work. It made more sense to get people together, and to get them what they need with the funds I had been accumulating and saving for the community centre.

I've been doing this with my girlfriend, volunteers, and friends, to be able to carry on for another 40 weeks, which would mean carrying on into next summer, culminating with the community centre donating thousands of seeds, planting tools, and equipment to all the community gardens in South-Central that need them.

What's been so amazing about having my own space is that it is flexible and responsive to what the needs of the communities are at a given time.

JDYou fundraised in 2017 with a Kickstarter campaign to support the The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project, and through selling works commercially, you give back to your community. This echoes socially engaged practices that use art market success to facilitate broader community work. How do you balance dealing with the market art and a practice imbued in urban politics, social, and community engagement?

LHThere's no way in the world I could separate the subject, the people, the community, and the context from the reward of the work. No way. Everything that happens with the work relates to people here and is of benefit to the community. If that exchange isn't happening, then the work just shouldn't be made or shouldn't exist.

The only way I can have a community centre relies on a certain amount of funds coming in, or rather back in. It is very seamless to work in this way, and it doesn't feel like I'm ever making a compromise.

I hire my friends who I grew up with. We all still have our lives here and have deep concerns about the growth and that advancement of where we're from. And that'll always be central no matter what any of us do.

It doesn't make sense to me that there aren't a million Black-owned galleries. It doesn't make sense that Black collectors who have supported me since the beginning of my career come up to me or my peers and complain about a lack of access.

As soon as I joined David Kordansky Gallery, I was pretty clear about certain works being made available only to Black collectors, and they were totally down with that. There's a lot of work to do, still so much work to do, but we're just taking it one day at a time.—[O]

1 Tina M. Campt, 'Quiet Soundings: The Grammar of Black Futurity', Listening to Images (Duke University Press: Durham and London, 2017), p.34.

2 For an overview of the Great Migration see Kelly Simpson, 'The Great Migration: Creating a New Black Identity in Los Angeles', KCET, 15 February 2012, https://www.kcet.org/history-society/the-great-migration-creating-a-new-black-identity-in-los-angeles