Maria Madeira: 'I always thought of a better world'

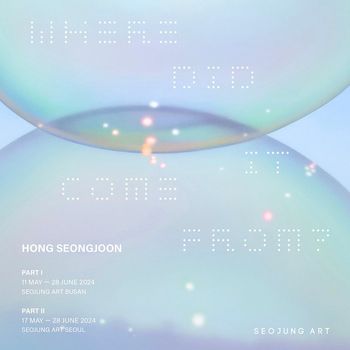

In collaboration with Timor-Leste at the 60th Venice Biennale

Maria Madeira with Kiss and Don't Tell (2024). Exhibition view: Timor-Leste Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere (20 April–24 November 2024). © Maria Madeira. Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne. Photo: Cristiano Corte.

Maria Madeira with Kiss and Don't Tell (2024). Exhibition view: Timor-Leste Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere (20 April–24 November 2024). © Maria Madeira. Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne. Photo: Cristiano Corte.

For the inaugural Timor-Leste pavilion at Venice, Maria Madeira uncovers some of Timor's painful histories to platform the resilience of its women.

On a sunny afternoon in April at the Spazio Ravà in Venice, Maria Madeira brought a dark period in Timor's history into the present, activating the space and shining a light on the experiences of women during the Timorese fight for independence.

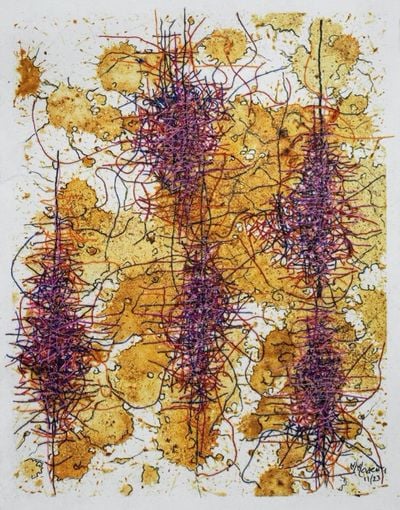

Madeira is one of Timor-Leste's foremost contemporary artists and the representative of the nation's inaugural pavilion, curated by Natalie King, at the 60th Venice Biennale. Titled Kiss and Don't Tell, the installation features a room of 25 hand-painted panels anchored by drifts of red earth and splattered with betel nut sprayed from the artist's mouth during her performance. At knee-height, lipstick marks reference those discovered by Madeira in a room in her village Gleno in Ermera, Timor, which had been used as a torture chamber during the Indonesian occupation. Madeira has stated, 'Men fought and we are forever grateful. Lest Not Forget: women also fought. And we are eternally grateful. For men fought with their guns BUT women fought with their bodies.'

A childhood of music and creativity instilled in Madeira a love of making—her father and grandfather were woodcarvers and makers of traditional drums and swords. But the 1975 invasion of Timor by Indonesia saw Madeira and her family airlifted to Portugal the following year, where she spent most of eight years in a refugee camp on the outskirts of Lisbon.

There she joined a Timorese choir and found comfort and pride in performing for Timorese and international audiences. She comments, 'In many ways, the choir was my salvation and I believe that it was one of the main reasons I became a visual artist. It was during these years that I understood and became aware of the power of creative expression.'

It's a power that is found in early works such as 270+ The Santa Cruz Massacre (1996). The installation features metal crowns commemorating the peaceful pro-independence supporters who were killed in 1991 when the Indonesian military opened fire in the Santa Cruz cemetery.

Madeira's use of media is political. For her, the materials of her country, such as betel nut, natural pigments like the red earth of Ermera in Kiss and Don't Tell, as well as tais (handwoven traditional textile), and the craft of sewing, give her work power, transforming the natural environment and culture of her home into evocative and meaningful works of art. In the earthy purples, reds, oranges, and yellows she documents the sorrow, pain, and resilience of Timor's women, giving voice to the many voiceless women who suffered, and continuing a process of self and national healing that reckons with the wounds of many years of colonial rule.

As Madeira prepared for the Biennale earlier this year, she and curator Natalie King engaged in conversations about her work and its origins in the storytelling, culture, and the harvesting activities of her village. The following conversation is an edited version of these discussions, originally published in the Timor-Leste Pavilion catalogue and republished in Ocula Magazine in collaboration with the Pavilion.

NKYou were born in the village of Gleno in the Ermera region of Timor-Leste. Can you describe some of the cultural traditions from your village and how these have influenced your art practice, in particular the use of tais and the ancestral creation story with crocodiles?

MMMy childhood in Gleno, Ermera, was very memorable and filled with cultural traditions. Some of the earliest memories that I often joyfully share with my siblings are about us being present at traditional ceremonies such as rice harvesting (Tebe Hare/Sama Hare in Tetun). Here, the locals used to step on rice husks while singing and dancing throughout the night. I used to love it because of the traditional rhythmic songs, all sung in Tetun or Mambai (local languages), to help with the rhythmic physical movements needed to separate the rice from the husks and stems. Such ceremonies often required people, both male and female, to use traditional East Timorese cloth such as tais to perform.

Likewise, storytelling was also a permanent feature in my upbringing. For instance, the legend of the crocodile whereby according to folklore Timor-Leste originated from the time a young boy first helped rescue a crocodile, which later returned the favour by helping the young boy to see the world, by becoming the Island of Timor. This mythology is told and retold to most East Timorese from a young age.

NKTell me about your childhood. Was your home creative?

MMIt was pure magic. My dad already had a camera and film for recording us playing, jumping and swimming in the river. Then, at night, we would have cinema—home movies. The whole neighbourhood would come to sit and watch these home movies of us just being silly in the water.

I was born near the river and it gets very wet during the wet season. Because there are lots of rivers and lakes in Ermera, it's a good area for coffee plantations. The earth is very rich not only with agriculture, but also for my spirit. The earth is so beautiful and that's why I love the red of the Kimberleys in Western Australia.

We always grew up with music. My grandfather and my father, they are into music. My dad bought some guitars, and then my brothers started playing. They are amazing musicians, guitarists and music writers. My dad is a great artisan producing wood carvings while my grandfather was a great wood carver as well. He made a lot of surik, the traditional sword and beautiful drums. My dad and I always had a very strong interest in Indigenous art.

I believe that these early experiences have helped me to appreciate and grow with traditions in mind. They have instilled in me an understanding, deep love and value towards my cultural identity.

NKIn 1976, the Portuguese Air Force evacuated you from West Timor after the Indonesian invasion. You spent most of the following eight years in a refugee camp run by the Red Cross on the outskirts of Lisbon in Portugal where you joined a choir. Can you discuss how song and collective singing became an outlet for you?

MMWhilst in the refugee camp, I became a member of a successful young East Timorese choir called Coro Loro Sa'e, which was composed of up to 30 young girls, daughters of the refugee families residing in Portugal. The choir performed extensively, especially traditional dancing and singing throughout Portugal and the neighbouring countries.

Kiss and Don't Tell . . . grew out of the need to tell some painful realities about the history of Timor-Leste's plight for independence.

It was my understanding that the main objective of the choir was to strengthen Timor-Leste's cultural identity while divulging and sharing it with other societies. During cultural and community events such as fairs, I noticed that when traditional songs and dances were performed, it frequently evoked emotional responses such as sadness and pride from both the East Timorese people and some members of the international community. This kind of reaction made me recognise the value, impact and power of creative language. In this case, traditional East Timorese music and dancing became an effective and efficient way of exposing our troubles and restoring some sense of belonging.

Thus, my experience as a refugee and singer with the East Timorese choir Coro Loro Sa'e was a fundamental factor in learning and growing because it encouraged me to take a closer look at my East Timorese background, to discover who I really am. For me the choir was critical in restoring my sense of worth and belonging. Every time I performed, I experienced happiness. I felt so proud and so free. It was as though I was being healed. Besides, getting away from the refugee camp to perform meant that at least we were going to be fed.

In many ways, the choir was my salvation and I believe that it was one of the main reasons I became a visual artist. It was during these years that I understood and became aware of the power of creative expression.

NKHow did you become an artist? Was there an epiphany?

MMAs long as I can remember, creativity was always part of my upbringing like the traditional ceremonies such as rice harvesting and choral work.

In the refugee camp my mother loved magazines and I just happened to turn the page, and there was this beautiful image of mountains and a lake: Lake Louise in Canada. So that was my first colour drawing that I'll never forget, because I did a drawing in my head. I copied the image of Lake Louise to a page, and I was very proud. Where I grew up, there's lots of water, so just seeing a vast amount of water in a landscape, reminded me of Ermera that is also mountainous. The image of water and mountain was captivating.

My artistic work grew and developed over the years. It started during my refugee days where I found peace every time I was drawing and sketching. With the joy and impact of the choir, it made me value art more and I was really captivated by the sense of wellbeing and sense of worth every time I created. Overall, I think it was a passion that evolved and developed progressively.

NKOne of your early works, 270+ The Santa Cruz Massacre (1996), is a floor installation that deploys the traditional kaibauk silver headdress worn by the Timorese liurai, shaped like the horns of a buffalo and configured into a cross formation. Can you discuss this commemorative work?

MMI try to reach both the western world as well as the East Timorese. I always use materials that I think will be recognised. I use the kaibauk for the Santa Cruz massacre installation. I talk to both sides. I'm able to reach out and communicate to both. There has to be an understanding, not only political understanding and religious, but on a cultural level. I use a creative and cultural language that we have used to understand each other, since the days of our foremothers and forefathers.

When the Santa Cruz massacre was shown on television, I thought, you are heroes and heroines. At the time, I went to a lot of protests against the military regime. Yet the media coverage was barely for three seconds on the news. I thought it needed more. We needed to talk more. I put the plus on the floor to say that 270 plus people died at the Santa Cruz massacre. They are heroes. They deserve a royal burial, a state funeral. I'm not screaming, my art just speaks and it's such a powerful tool.

NKFor the 60th Venice Biennale, you are making an ensemble exhibition called Kiss and Don't Tell. What is the inspiration for this installation and the role of cultural activism?

MMKiss and Don't Tell was an inspiration that grew out of the need to tell some painful realities about the history of Timor-Leste's plight for independence. Particularly the voice of minority groups such as women.

After returning to Timor-Leste, I observed and learned about the atrocities committed against the women of Timor-Leste by the Indonesian military. In their honour, I thought that it was critical to tell these stories, to create awareness for future generations to come. Men fought and we are forever grateful. Lest Not Forget: women also fought. And we are eternally grateful. For men fought with their guns BUT women fought with their bodies.

I was staying with my brother and sister-in-law. At the time, my brother was working for the U.N. as an interpreter for the serious crimes unit and I joined him as a translator. Around this time in 2002, I was staying in a bedroom where I found myself staring at lipstick stains, month after month. When I understood, I realised it was trying to tell me something. I decided: I am going to talk, I am going to kiss and I am going to tell.

In short, Kiss and Don't Tell talks about the impact and influence of East Timorese women during the occupation. It talks about how strong the women were and how their fight, resilience, survival, and triumph led to the freedom of our mother land.

NKEducation, learning and pedagogy have been important to you especially since you have completed a PhD at Curtin University and worked as a teacher. Can you discuss?

MMYes, I have always maintained that education was a key factor for personal growth and understanding especially in relation to Timor-Leste being such a young nation. This country was hidden behind closed doors for decades whilst being occupied by a foreign country. Due to the occupation, many East Timorese were killed and displaced.

For me, it was again the urge to find a sense of belonging and survive the cultural, political, social and religious realms. As a young refugee, this plight became more critical. During those difficult times, I always thought of a better world. 'Life must be better than this,' I often thought to myself.

Everything is about the ground for me, it keeps us embedded into being Timorese.

In regard to my artistic expression, education was a tool to help me grow, better develop and advance my practical perspective. I felt that it was crucial to add a voice to my visual art. And with a formal education and a PhD, I could get more attention. I am asked to participate in all kinds of art and cultural events. I can educate in both practical and theoretical areas in art. I am heard.

More importantly, I believe that education is the best vehicle to create interest and awareness about the current diverse art and culture language. For instance, by teaching the young artistic generation "up to date" and "current language" of art, young people will find their own curiosity to travel to the past in order to find themselves in the present.

NKThere is a unique materiality to your work sourcing materials that you find such as tais, earth, betel nut. Can you elaborate on how and why you utilise found materials that belong to your homeland?

MMSince returning to Timor-Leste in early 2000s I soon came to learn we don't have a proper art material shop in the country. We don't have an official Art School. As a form of survival I thought, 'What about the natural resources?' Betel nut? Natural dyes? Red earth? Rock powder? Even traditional items such as the kaibauk, and of course our traditional textiles called tais.

In the end, the tears will flow into streams and rivers to create growth. And that's our strength.

I started to use these materials in my work. I believe that it is very effective. Firstly, because I could gather these materials quite easily around the country. Secondly, and most importantly, by using East Timorese objects and imagery meant it also spoke to the people of Timor-Leste. Thus, each work can generate interest and curiosity from a national and international level. This made each artwork much more significant.

In terms of using the red earth from Ermera, I have been thinking about the footsteps that you walk on and when you feel pain, you fall to the ground. Everything is about the ground for me, it keeps us embedded into being Timorese. In sacred ceremonies and folklore, we talk about Mother Earth and our umbilical cord is buried next to the most prominent tree as our oldest eternal connection to Mother Earth. Ermera has such a beautiful red coloured earth that I just can't ignore it. Everywhere I go I get stained, if it's on a very dry, windy day, your face gets all red with mud particles.

I love the red, the blue and the yellow as part of my composition of my work, because for me they bring a lot of beautiful violet purple colours that represent sorrow. You die to grow, to be born again. The women are being sorrowful yet there's hope because we overcame. So the purple really connects very heavily to my work. And then, of course, the orange, because it just looks beautiful. I think red earth is red earth. Orange earth is a miracle.

I tend to collect leftover tais from all the sewing, the offcuts from the sewing, like from Timor Aid and from the Alola Foundation. I have a lot of leftover beautiful loose cotton that I can just use as a painting with tweezers while the larger portions, I tend to cut into lips. A cut in a void is a wound. I also burn the edges, and then I stick the tais on the background like burned imagery. It's very effective, like soft pain.

My vision of Dili when I first arrived was the smell of burning especially all the houses and timber. We had to contend with the stench of burning from the militia rampage. Then, through the smouldering, I saw Dili grow from the ashes. There were a lot of burned houses that were occupied by the U.N. We lived under conditions of destruction, predominantly by fire. The next year the flowers grew again, it's a rebirth from the ashes. I tend to use a lot of those elements that I know will make the story much stronger, so that the work speaks louder if I add the truth. In the end, the tears will flow into streams and rivers to create growth. And that's our strength.

NKFor the Venice Biennale, you will perform during the opening days, singing traditional songs in Tetun as part of your installation with stories of pain, loss, and anguish. How is performance a way to complete the exhibition cycle?

MMYes, for the Venice Biennale, I will carry out a performance to enhance the story and share the idea and influence behind the installation work Kiss and Don't Tell.

This idea relates to my belief in adding voice to the visual. With my artworks, I always want to tell a story. I always want to convey a message. I always hope to evoke some emotional response (whether positive or negative). Because this is my way to communicate more in depth.

I believe the performance will add better understanding to my site-specific installation. It is a story about Kiss and Don't Tell that I want to "kiss" and "tell". —[O]