Ibrahim Mahama: ‘I'm interested in art for the sake of life itself’

Ibrahim Mahama. Courtesy Barbican Centre. Photo: © Christian Cassiel.

Ibrahim Mahama. Courtesy Barbican Centre. Photo: © Christian Cassiel.

The Ghanaian artist discusses his Barbican commission, curating the 35th Ljubljana Biennale, and Ghana's rich art ecologies.

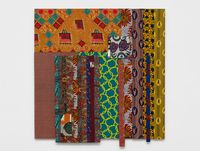

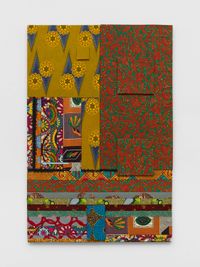

Ibrahim Mahama's installation Purple Hibiscus (2023–24) was unveiled this week at the Barbican's Lakeside Terrace, which is now wrapped in 2,000 square metres of vibrant handwoven and embroidered cloth, made in collaboration with over 400 craftspeople from Tamale, Ghana.

Purple Hibiscus is Mahama's first major public commission in the U.K. and continues a trajectory that can be traced back to one of his best-known installations, Out of Bounds (2014–15): as part of Okwui Enwezor's 56th Venice Biennale, the artist covered the walls of an external corridor at the Arsenale with quilted jute sacks. Other jute interventions include the wrapping of the Torwache gatehouses in Kassel for documenta 14, Check Point Sekondi Loco. 1901–2030 (2016–17), and TRANSFER(S) (2023), which covered a former shopping mall in Osnabrück with strip-woven textiles, batakari smocks from Ghana, and jute sacks.

Mahama's use of jute sacks refers to the histories of trade and resource extraction that have shaped the global economic system since the colonial era—a system that Ghana's first president, Kwame Nkrumah, sought to challenge as Ghana gained independence from the British Empire. The artist's two-channel video Exchange Exchanger (2013–16) documents the making of these works: old sacks used to store cocoa beans, one of Ghana's main exports, are swapped with traders for new ones and stitched together by women, before the resulting fabric is transported to the building that labourers wrap.

The first architectures Mahama wrapped were in his native Ghana. For No Stopping No Parking No Loading. Unity Hall. 1957–2057 (2015), Mahama covered the modernist hall of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Kumasi, where he received his BFA and MFA under the mentorship of professor Karî'kachä Seid'ou.

KNUST has played an important role in the development of Ghanaian art. In 2015, its professors founded the transgenerational and transdisciplinary blaxTARLINES collective, recently listed in ArtReview's Power 100, of which Mahama is a member.

Other buildings Mahama has wrapped include grain silos built in Ghana in the era of Kwame Nkrumah. These silos were part of Nkrumah's campaign to establish Ghana's economic independence in the face of neocolonialism, a term Nkrumah coined to define economic capture as a tactic by former colonisers to maintain power.

Reflecting Mahama's deep engagement with Nkrumah's political, philosophical, and intellectual legacy, the artist opened Nkrumah Volini in 2021 in Tamale, his hometown, in an abandoned silo. Described as an 'institution for archaeological memories, ecological ideas/forms and thinking future forms', the space joins two others that Mahama founded in Tamale: Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA), launched in 2019, and its adjacent Red Clay Studio, which opened in 2020.

The latter's red-brick hall was reproduced for an iteration of Parliament of Ghosts at the São Paulo Biennial in 2023, the year Christian Guerematchi used it as a set for Črni Tito – Blaq Tito Addressing the Parliament of Ghosts (2023), a commission for the 35th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts in 2023, for which Mahama served as artistic director. In the video, Guerematchi performs as former Yugoslavia president Tito; in one scene he speaks from one of the Soviet-era planes parked on Red Clay Studio's grounds.

Anchored to history of the Non-Aligned Movement—co-founded in 1961 by Nkrumah and Tito alongside Egypt's president Gamal Abdel Nasser, and Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first prime minister—the 35th Ljubljana Biennale, titled From the void came gifts of the cosmos, marked a significant expansion in Mahama's practice.

Working with curators Exit Frame Collective, Selom Koffi Kudjie, and Patrick Nii Okanta Ankrah, members of blaxTARLINES, and Inga Lāce, Beya Othmani and Alicia Knock, the project extended a red thread connecting Mahama's works: of Nkrumah's role in the Non-Aligned Movement and what it means for Ghana and the world at large.

In this conversation, Mahama discusses his ideas behind the Ljubljana Biennale, elaborating on how they connect to an extraordinary practice that moves dynamically across scales, from local to global, public to private.

SBHow did your role as artistic director of the 35th Ljubljana Biennale connect to your interest in the Non-Aligned Movement and the legacy of Kwame Nkrumah?

It's a fitting triangulation, given the Ljubljana Biennale was founded in 1955 in the context of the Cold War's so-called East, the same year documenta was launched in West Germany and the Bandung Conference took place.

IMIn the art school where I studied, the East was always important. Particularly events around the Cold War, given the collaboration between the East and Sub-Saharan Africa. There were many infrastructure projects taking place at the time when African states were gaining independence.

Nkrumah was one of the chief exponents of this era. Focused on moving away from the colonial legacy, he collaborated with countries in the East that didn't have much to do with colonisation, including Yugoslavia. He visited Ljubljana a couple of times. A photo of one visit shows school kids lined up on the street with little flags, with a poster in the background that reads: 'We welcome our friend from Ghana'.

At the time, Nkrumah was embarking on major infrastructure projects in Ghana. Architects and engineers from Yugoslavia, Poland, and Russia came here to build and do research, while students from Ghana went to Yugoslavia to study engineering, agriculture, and other subjects. Some stayed, got married, and raised families. Some returned to Ghana.

Nkrumah is important not only for the physical infrastructures he created in Ghana; his ideological position shows he was thinking large, with the future in mind. In his independence speech, he said that the independence of Ghana is meaningless unless it is connected to the liberation of the entire African continent.

One important thing that Nkrumah did was rename Ghana. It was previously called the Gold Coast because of the gold the British extracted, together with other colonial powers. Nkrumah chose Ghana, after the ancient Empire. But the name was more of a dream; an archaeological exercise of going back in time to excavate a moment when people were truly free and managed their own destiny.

. . . it was important that the [Ljubljana Biennale] would give people the chance to converse and interact with each other . . .

My professor at art school, the scholar Karî'kachä Seid'ou, was interested in what has been neglected since Nkrumah was overthrown. There was a lot of propaganda around that time. During the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, people believed the concrete silos Nkrumah was building were nuclear bunkers or detention centres constructed with the Soviet Union. None of this was true.

As students born 60 years after these events, we found ourselves asking: How do we go back in time? How do we reconnect with and reinterpret these memories, and how do we return them to unborn generations? That's where the concept for the Ljubljana Biennale came out [of].

I found [the Biennale] an interesting opportunity to go back in time. But I was not only thinking about historical time. I thought about the directions a biennial could take by exploring political questions, of the exhibition as an opening point or portal for future conversations.

SBThat makes sense. Your work in Ghana connects to the Biennale's theme of bringing forth new universes from the void, which resonates with Nkrumah reaching into the past to create pathways out of colonialism.

The name of the silo you bought and transformed into an experimental space in Tamale, Nkrumah Volini, meaning 'inside the hole', actually refers to the void.

IMThat silo was one Nkrumah built, which was abandoned. I bought it from the state and converted it into a public institution, where we invite school children and give them tours of the building. Even if the building is not being used for an exhibition, what we do is bring the building to life. And that allows for many different types of interactions. My studio also functions the same way—I open it up.

I'm interested in art for the sake of life itself. We must try to create contexts and forms that can allow discourses to thrive.

SBThis idea of opening up resonates with the Biennale. My impression is the curatorial team was free to develop the show, but you were more hands-on in the selection of the external sites—PLAC, SVS Studio, and Krater, for example—where you found resonances with the work you are doing in Ghana.

IMWhen I went to Ljubljana for site visits, I asked to meet collectives or artists working outside of the traditional framework. I was interested in how ideas that I had been working and struggling with in Ghana connected to forms that these collectives were developing in Ljubljana.

When I met with Krater, for example, I immediately knew they had to be central within the exhibition because they were dealing with occupying space in real time, making choices around form, and dealing with the politics around that. Krater works in an organic ecosystem growing in a massive pit in Ljubljana, building physical, human, and ecological infrastructures.

It was important to show this way of working by allowing people to visit the site. For me, it was important that the exhibition would give people the chance to converse and interact with each other, as I do in Ghana.

SBA search for ways of working that resists capitalist progress, as developed within the context of colonial modernity, is palpable throughout the Biennale. Whether in PLAC, an autonomous zone resisting gentrification, or in works like High Dam (Concrete Poetry) (2023) by Ala Younis, highlighting the politics of economic postwar development—what Nkrumah named 'neocolonialism', but what we would perhaps call neoliberalism today.

IMExactly—neoliberalism. Recently, in light of the situation in Gaza, I've been reflecting a lot on that. Because Nkrumah, together with many pioneering African leaders who were either assassinated or overthrown, fought against neocolonialism, and of course, America is one of the champions of that system. Sometimes I find myself asking, is this the same America that sent the Hubble telescope into space to allow us to discover the universe? Is this the same country sending weapons to Israel? Are these the same people who are funding art? With all the progress we have seen in the world, how are we still in this cycle?

. . . the most important question is how to restore a true sense of independence within the world that we find ourselves in . . . We don't have to take whatever the art world gives us.

Even the art world—which claims to be interested in world politics, true democracy, liberation movements, and issues of justice—always seems to crack down whenever there's a real crisis. If anyone stands with a movement because they come from a history of oppression, it's suddenly: 'How dare you?' But why shouldn't we support oppressed people? That's the only thing we should do. It is what art speaks for.

It's important to ask these questions, as they deal with the contradictions within the world and the art world itself—and we've always dealt with these contradictions in this part of the world. But it seems there are always people looking for a chance to crush everything when it comes to engaging with these wider narratives. If we cannot have these discussions, I don't think we are going to see progress.

I always try to stay optimistic, though, because there is a lot of promise, despite the precarity—especially if we push to create new narratives. I'm not even interested in art for the sake of history. I'm interested in art for the sake of life itself. We must try to create contexts and forms that can allow discourses to thrive.

SBSpeaking about thriving, your directorship of the Ljubljana Biennale has both emphasised and expanded the scales that define your practice, from the institutions you are developing in Ghana to your work with the global gallery system. How do you navigate these scales? I'm especially curious about the dispute you had with one collector and a dealer early on in your career. They purchased your jute works and cut them into smaller pieces to sell without your permission, which says a lot about how art market power brokers can deal with artists.

IMI knew I had to take a strong position on that scandal. If I was not careful it would kill my practice before it began. That's why the lawsuit came up; I just said no. At the time, I had been invited to documenta, but I think the establishment wanted nothing to do with the scandal, so the invitation was held back until it passed.

. . . as students we asked: how do we shift away from this idea of commodification?

But it was important for me to retain that invitation. For one, my participation would validate the work of my professor, Karî'kachä Seid'ou, who fought to teach alternative ideas, approaches, and forms in Kumasi. At the time, it was doubted that teaching students about making radical work would pay off, and my participation in a show like documenta was a promise for those who came after me.

Historically in Ghana, artists show work in hotel lobbies and spaces like that, because there is no investment from or for institutions. That's why teaching students to make art that cannot be shown in places like hotels becomes a problem. Nkrumah was the only president who invested in constructing a national museum, but the building was abandoned after he was overthrown.

Though I knew the art world was geared or centred towards commodification, I remember as students we asked: how do we shift away from this idea of commodification? I was interested in making works that were impossible to show or sell. Even now, I deliberately create works that even an institution like Tate Modern could not contain.

SBThis idea of resisting containment by creating works that exceed the scope of the institution or market resonates with the spaces you have created in Ghana. Could you talk about that?

IMWhen I wake up in Ghana, and I'm walking outside in a compound, there are goats and cattle walking around. Sometimes I go into a permanent collection and there's a goat sitting in the corner, and bats flying around.

Modern art institutions in the West were not built that way. They were built to cut out the real world. Once you enter the Western museum, you enter its paradigm. With the spaces I am developing in Ghana, we want to deal with the conditions of the real world and bring them into the museum, studio, or institution.

At the beginning of art school, professor Seid'ou asked us: how do we transform art from a state of commodity into a gift? How do you work with precarious conditions to create new paradigms? If you draw from the precarious subject matter around you, how can you make sure the artwork does not only exist in a museum as something that people cannot access?

But the most important question is how to restore a true sense of independence within the world that we find ourselves in. As artists, we need to be self-aware enough to realise we can make proposals beyond the art world, which can change how we experience art from different parts of the world. We don't have to take whatever the art world gives us.

SBThat striving for true independence connects your education under professor Seid'ou to Nkrumah's definition of neocolonialism to highlight the anti-colonial economic struggle for true autonomy in the capitalist world system. How does blaxTARLINES fit into this?

IMThe blaxTARLINES alliance was founded by professors in my art school just after I graduated. They really founded the collective for their students, and we automatically became part of the collective. We also invited people from other disciplines to join—from mathematics, physics, architecture, and other departments—and people who were not in the school but were aligned with our politics.

The idea was to instil a sense of independence among students, while advocating for the collapse of boundaries between different schools at the university, like fine arts, industrial design, architecture, or civil engineering. We needed to rethink how we talk about our practices as transdisciplinary, ranging from creating art to building institutions. Eventually, the school established the College of Art and Built Environment.

When it came to launching SCCA in Tamale, I emerged from blaxTARLINES and returned to the north, where I was born, to build new institutions. At the time, I asked myself how I could connect the paradigm that blaxTARLINES established to what I was trying to build.

blaxTARLINES is an important part of Ghanaian art history, in terms of looking at and moving away from art historical forms, engaging with traditional crafts, while inventing new forms, new languages around material use, and contributing to the development of the art scene in Ghana generally. Without this movement, things might have become purely market-driven.

At the same time, blaxTARLINES is based on the idea that, first and foremost, we have to think about economics, because that is part of our drive to develop new systems, which is where non-alignment comes in. While it's difficult to describe the movement as one thing, since individuals have their own approaches, the intention is to collectively strive for true emancipation in terms of practice.

SBThat emancipatory focus relates to White Cube Lusanga, where you held your first solo institutional show in Central Africa in 2022. What is your take on the White Cube project, given the criticisms of Renzo Martens, who initiated the project to reroute art world money to this artistic community in the Congo?

IMCongo was one of the few places Nkrumah wrote an entire book on, and I went there for the first time in 2018, around the time of the Lubumbashi Biennale. The place raises pertinent questions, given the genocides that occurred under Belgian colonisation.

As artists, how do we engage with such a context? Especially if you're Renzo Martens, a white artist coming from a Western position. People say a Dutch guy has no right to come to Africa and make work like this, but my position is to look at him as an entity, a character, while considering what a project like White Cube represents in a place like Lusanga.

. . . the whole point of contemporary art isn't to stay within the European perspective; it is to open it up to the rest of the world.

Many artists and artisans were born in Lusanga and live there. Their reality is a lack of proper infrastructure, schools, and the like. The land is destroyed through years of monoculture farming by Unilever, which used to control the plantation where White Cube was built.

White Cube Lusanga is trying to make use of the art market. They sell work and use the money to buy back land and repair the damage that has been done. Martens was an interesting catalyst because he brought attention and money. While one could argue he is using the situation for his benefit, the project is about the artists working with that space, who mean what they do, and depend on its success. That's more pertinent when thinking about White Cube Lusanga as a form of repair and restoration.

When I did my exhibition there, I was unable to go myself. My studio assistants went with SCCA's artistic director and other colleagues. They talked about how difficult the conditions were, even compared to Ghana. It was important for them to see that because many people who criticise this project have never been to Lusanga. If you don't go there, how can you analyse or judge the work being done?

SBFor your recent project in Osnabrück, you wrapped the former Galeria Kaufhof with a tapestry created with the local community. Given your jute wraps started in Ghana, what has it been like to transfer this work to places like Germany through the years?

IMI approached Osnabrück from the history of the German occupation in Western Togoland, part where I come from, the Dagbon Kingdom, in relation to the European Treaty of Westphalia, whose peace, announced in Osnabrück in 1648, gave birth to the whole colonial enterprise.

To create an exhibition around this intersection, we connected the traditional batakari smocks we have in Ghana to the history of textile production in Western Germany. We covered an old shopping mall, once a symbol of economic growth, that had closed, which agitated a few people. They didn't understand why the municipality would spend money to commission an artist to bring old materials from Ghana to wrap a building that reminded them of the region's failed economy.

But I saw this as an opportunity because my work is also about the discourses that surround the physical work. When we invited people to participate in the work's production, many different people came: older people, younger people, students as young as ten, university students. Every day, we discussed the materials and where they come from, opening up discourses around what colonialism meant and what neoliberalism means now.

We spoke about how batakaris were traditionally passed down through families, making them a form of sustainable fashion, in contrast to clothes sold in shopping malls, which are often just selling trends. We talked about global production, and how European companies make garments in places like Bangladesh, where European rules don't apply, resulting in harm to workers and environments due to the lack of regulations.

. . . new connections need to be made and alliances formed around how we exchange ideas and labour forms.

Of course, there are contradictions in the work. For example, materials were brought to Germany on the plane, and some journalists focused on carbon emissions. I also realised that there were certain biases in how the media covered the project. Some focused on the money spent on a foreign, non-European artist. But the whole point of contemporary art isn't to stay within the European perspective; it is to open it up to the rest of the world.

In the end, the experience reaffirmed the choices I make to work with people locally in Ghana—with artisans who produce things here, like textiles or pottery, and bricklayers and others who help build these institutions. The most important thing is to work sustainably.

SBWhat strikes me is how your practice is all about learning by working with people; and your artworks are tools that help deepen your understanding of the systems and conditions in which you work.

IMYears down the line, I have become more interested in the different spaces and the political conditions of the production of these works. For example, for the Venice Biennale in 2015, the idea was to travel with about ten collaborators from Ghana, but the Italian ambassador didn't understand the work I was doing and thought I was taking people abroad who would never come back. So the visas were never issued. For a project in Germany in 2018, we sent the material to Germany, where we worked with students to put the work together, which was really quite brilliant.

For my show at the Barbican, I'm working with these textile forms. But while weavers did everything by hand before using machines to stitch the pieces together for the Osnabrück project, in London I wanted to return to this idea of physical labour, so we ended up working with 450 people almost every day for two months to stitch the fabric by hand on a football pitch. We've made a film about it.

SBThinking about how directing the Ljubljana Biennale has expanded the scales and spaces you work with, where will your practice go from here?

IMLjubljana was a good exercise because it reminded me of the work that needs to be done within the art world—new connections need to be made and alliances formed around how we exchange ideas and labour forms. I've learned from the experience, along with other recent projects and encounters, how to be more generous and open up this generosity.

Across my work, I try to propose ideas that can also be disseminated around the world—the idea is not just for the work that I'm doing in Ghana to stay here. Coming from a specific area gives you specific ideas of the world in terms of political positions and approaches. That was important for me to realise, and it reinforces the idea that we need to be more generous with how we think about making art. —[O]