Jonathan Jones on Telling All the Stories

Jonathan Jones. Photo: Mark Pokorny.

Jonathan Jones. Photo: Mark Pokorny.

Wiradyuri and Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones is known for a practice that celebrates the power and resilience of Aboriginal Australia, anchored by extensive research into his subject and his collaborative engagement of community.

The artist's latest exhibition, untitled (transcriptions of country) (15 December 2023–11 February 2024) opens at Artspace, Sydney, as its inaugural exhibition after extensive renovations. First seen at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, in 2021, the exhibition takes as its departure point Frenchman Nicolas Baudin's scientific expedition to Australia between 1801 and 1803. Jones questions received wisdoms around the colonial trade in Aboriginal cultural objects as well as the European processes of removing, collecting, and storing these objects.

Baudin's expedition took Australian flora and fauna samples, as well as Aboriginal cultural objects, to France where they became part of Joséphine Bonaparte's collection at Château de Malmaison. Of these items, only a series of portraits of Aboriginal people and several drawings of cultural objects remain, made by French artist Nicolas-Martin Petit [the original drawings are by Petit and the lithographs by Barthélemy Roger] during the expeditionary voyage.

untitled (vases, armes, pêche) (2023) uses Petit's drawings of the original objects as a guide in the casting by Australian ceramicist Somchai Charoen of 206 tools, spears, and vessels in white porcelain. Acknowledging the objects' loss in Europe, Jones scatters them beneath the antique European tables of untitled (emu eggs) after Étienne-Pierre Ventenat (2021–2023) which are bedecked in yellow paper daises and emu eggs carved with native Australian plants.

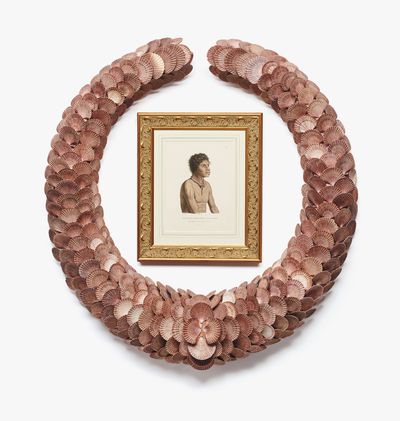

The series 'untitled' (2021) co-opts Napoleon's use of the originally Greek, then Roman, laurel wreath—a symbol of victory. For these works, Jones has enveloped Petit's portraits of Aboriginal people in wreaths, each made from a different plant or animal-derived element—emu eggshells, black swan feathers, scallop shells, gumnuts, paper daisy flowers, and possum fur—in an act of remembering and memorialising. But rather than burying these ancestors, Jones wants to remind viewers of them and reclaim their lives, with the fauna and flora wreaths placing them firmly back on country.

A collaboration with members of ACE Embroiderers Collective, along with the Adornd group and other individual participants, has produced a series of 308 embroideries in a contemporary intervention in the colonial act of collection and documentation. Members of the Sydney Aboriginal community and ACE Embroiderers Collective, including migrant women from Afghanistan, South Korea, and India, engaged in a two-way process of exchange that saw Indigenous participants educating the women on Australian plants, and the women sharing stories of their displacement and experience of conflict.

I spoke with the artist on the eve of his exhibition opening about his work's exploration of Australia's complicated and multifaceted histories and the key to contemporary and future ways forward for all Australians.

SAYour exhibition untitled (transcriptions of country) at Artspace explores the history of colonial transportation and trade between Australia and France where Aboriginal cultural objects and Australian native plants and animals were transported to France and became part of Napoleon and Joséphine Bonaparte's private collection at Château de Malmaison. Can you talk about your research into these histories?

JJThe project looks at the collections made by the French during their expedition to Australia between 1800 and 1803, under the command of Nicolas Baudin. The voyage took place just after the French Revolution and I imagine that ideas of equality impacted the way these collections were made, especially in relation to the way Aboriginal people were treated and depicted, which is quite different to how they've been historically depicted by the English.

Captain Baudin was not from a noble family, so could not captain a ship in pre-revolutionary France. He left France and worked in other countries, returning after the French Revolution when he was able to become a captain. Something of his nature is embedded in this project. I'm not saying that he's a nice guy and his version of colonialism was great, but something happens when we see Australia through the lens of a revolutionary Frenchman.

There's a fantastical layer to this story: at the time, people thought Australia could be made up of two islands separated by an inland sea. To test this idea, the French were enlisted by Bonaparte to undertake scientific research led by Baudin, but at the same time, the English sent Matthew Flinders to undertake the same project. So, the two voyages to circumnavigate Australia are happening simultaneously.

It is an interesting moment in Australia's history when these two histories are playing out and generating very different stories. The French are not perfect, but when they land in Tasmania, for instance, they come across Tasmanian women who are having a ceremony. Everyone's a bit shocked at meeting each other. The French decide to sing their national anthem to the women and the women reply with a song. And then this engagement ensues.

In Sydney, the French produce these extraordinary portraits of Aboriginal people that you can see in this exhibition and are the first to record and score Aboriginal songs. Whereas the English encounter Aboriginal communities in the Gulf of Carpentaria and end up shooting people. There's a discrepancy of cultural norms here.

SAThese portraits of Aboriginal people are centred in your series 'untitled' (2021), which can be seen in this exhibition. Could you tell us about this series and how your addition of the wreaths of flowers, feathers, plants, shells, fur, and eggshells around the portraits alter the reading of them?

JJI wanted to honour the sitters and make people more aware of them. The idea for the wreaths came about in thinking about Napoleon Bonaparte. Partly famous for crowning himself, he was adept at understanding and working with symbols and icons. Napoleon adopted the laurel wreath, which was used by Roman emperors to signify victory, but its origins go back further to Greek mythology. This politicisation of plants was an interesting act for someone who had his eye on taking over the world.

Australia will never move forward until it reconciles and comes to terms with this complex, interesting, and wonderful history that makes us who we are.

When you speak to Aboriginal people, you find that we're interested in the power of plants, too. So, we decided to make wreaths to sit around those portraits, to hold and remember them. Each material references those collected by the French in Australia.

The fur wreath, for instance, relates to the French taking living kangaroos, wombats, and possums back to France, to Joséphine Bonaparte's estate of Malmaison. Others are made from emu eggs, shells, and plant material, which the French also collected.

There is also a research element behind the work, which was undertaken with the late Keith Vincent Smith, a Sydney-based historian who specialised in local Aboriginal history. We commissioned Smith to write biographies of the individuals depicted. These short bios appear in the catalogue, and we get to know these people a bit more.

SAIs the collection still intact in France?

JJMost of the original drawings are, along with the botanical collections and animal specimens, but the cultural objects are lost. Everything was taken back to Le Havre, which is the port the expedition left from and returned to. Strangely, a few original drawings appeared a couple of years ago and were auctioned, which is odd because they are the official property of France.

After the expedition, the French published a book on the voyage [François Péron, Voyage de Découvertes aux Terres Australes (Voyage of Discovery to the Southern Lands), 1807–1816], which included these portraits. We used lithographs from the publication in this artwork.

SAYour work often deals with cultural loss—how, through the colonisation of Australia, Indigenous cultural objects were stolen, removed, and misplaced. barrangal dyara (skin and bones) (2016) at Royal Botanic Garden Sydney, for instance, responded to the loss of Indigenous cultural objects in the Garden Palace fire of 1882. Your work at Artspace also deals with cultural loss and what you have called 'the repercussions of forgetting'. What does telling these stories and remembering mean for you and your practice?

JJThere's a couple of edges to that. The overriding, important factor about this project is in addressing this single-mindedness around Australia's history, which is dominated by an English narrative. The Dutch, French, and Makassar engaged with Australia long before Captain Cook, yet this is not widely acknowledged. It's important to remember these alternative Australian stories, which illustrate that what happened with English and Aboriginal relationships was not inevitable, which is an idea that is constantly reinforced.

Remembering these stories is part of Aboriginal people trying to piece together fragments and hold that knowledge together. Elders and other artists before me have done it, clearing the pathway for me to undertake this work.

I hope that the more we investigate and expose these histories, the more the next generation can move forward. Uncle Bruce Pascoe describes this idea in his book [First Knowledges Country, 2021, co-authored with Bill Gammage] as defying our own intelligence by not wanting to know. Australia will never move forward until it reconciles and comes to terms with this complex, interesting, and wonderful history that makes us who we are.

SAOn the subject of piecing together fragments, the installation untitled (vases, armes, pêche) (2023) features 206 newly made white ceramic pieces that appear to stand in for the original, perhaps missing or lost, object—whether a shield, spear, or fishing tool—reminding me of the museum practice of filling in missing pieces of a sculpture or porcelain artefact with plain grey or white material. Could you speak about this work? What does this whiteness offer, express, or deny?

JJThe installation includes 206 objects, which is the number of objects recorded and unloaded by the French expedition. We don't know if they were all Aboriginal, but we do know that there were Tasmanian and Sydney objects.

This was potentially one of the biggest collections of Aboriginal material from Sydney that we know of. However, the story remains unknown to many French people. Today, there's probably only a handful of objects from Sydney left from this initial contact.

The objects were taken to Malmaison and installed in Joséphine's private museum, but the collection was subsequently lost. There are theories that the Germans took them after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, but no one knows for sure.

How we come to terms with that loss is difficult, but we have French documentation in the form of etchings of these objects. We recreated the objects based on these images, casting them in clay, and making approximately 24 of each kind.

When we engage in a process of exchange—objects coming back in exchange for new objects or projects—it allows us to maintain conversations with colonial institutions.

Strangely, the whiteness of these casts offers a little hope; they are almost like blank sheets that we can inscribe or reimagine the missing originals through. They are like bones or ghosts of these lost objects. Within a southeast Aboriginal context, whiteness also evokes funerals, when people use white clay to make objects or ochres for body painting. For me, the work speaks to the history of how we remember things.

When I met Philippe Peltier about 20 years ago, then curator at Musée National des Arts d'Afrique et d'Océanie, Paris [now Musée du Quai Branly] I asked him about the possible whereabouts of these cultural items. He said they could be anywhere, in an attic or under a table at Malmaison! This is why we threw the cast objects under tables in the installation of the work in this exhibition.

SAI find it very difficult to believe that nobody knows where these objects are. That's extraordinary, isn't it?

JJYes. Even after researching this project, I'm still not clear on the whole picture. It is difficult to understand how objects in collections can go missing.

But when we look at Sydney's history, the trade of Aboriginal material was so great that Governor [Arthur] Phillip had to issue a special order forbidding anyone from touching Aboriginal belongings, because convicts and marines would take them.

Despite such a massive trade, today we have only a handful of objects representing the entire Sydney basin. So, although there was huge interest and trade, there was no care nor responsibility, which is very difficult for Aboriginal people to come to terms with.

SAIn the context of your practice and its concerns around cultural heritage, how do you view the recent and ongoing repatriation of cultural objects by international institutions? Is it happening fast enough and in the right ways?

JJRepatriation is a positive thing, but it's a complex issue to determine where objects came from; that is, who owns them, and understanding the context in which objects were taken. We know from records that things were taken without consent, and from massacre sites.

But we must also be cognisant that there was a moment when Aboriginal people engaged in that trade and made objects. If we don't recognise that, we don't acknowledge our agency. I'm interested in that transition: when our people started to take control. So, I imagine some of the material sitting in museums wasn't stolen but traded by Aboriginal people.

It is incumbent upon us to get to the right people involved, to seek their permission, and engage them so we can have conversations that aren't possible on our own.

I can only really speak for the southeast, to New South Wales and Victoria, but it is very difficult to determine where the material comes from and which community. I've seen instances of object misattribution by museums: just because the collector was living in a certain town doesn't mean that objects came from that place.

Another important aspect is the opportunity for future generations of the community to research overseas and have a relationship with these institutions. When we engage in a process of exchange—objects coming back in exchange for new objects or projects—it allows us to maintain conversations with colonial institutions.

SAGiven that your work is so strongly about place and country, do you feel this exhibition was perceived differently in Paris compared to how it will be seen at Artspace in Sydney? Was the French audience across the ideas around the exhibition?

JJThe exhibition straddled Covid-19, so I couldn't go to France and have that direct relationship, but working with the institutions, I did find a lack of cultural understanding on issues like ICIP [Indigenous Intellectual and Cultural Property].

Thanks to Terri Janke, who specialises in this area, and other amazing Aboriginal people pushing things in Australia, we have a better understanding of these issues.

I did notice hesitation in museums around repatriation and what that looks like within French colonies. As you can imagine, there is a lot of material from Africa, and African curators and communities are doing extraordinary work in the repatriation space.

While I was there, the French government released a report that squashed the ongoing argument often posed by institutions to Indigenous communities, which is that they have the means to look after these objects, so they shouldn't be returned. The report found that it is incumbent upon the French government to pay for necessary resources to allow for the return of objects. This seemed to raise a few French eyebrows.

SAYou often work collaboratively, and the exhibition includes several works made with artists and groups including ACE Embroiderers Collective; a video work by Jazz Money; and a soundscape by Lille Madden. What do these multiple contemporary voices bring to your practice?

JJCreating collaborative works is a much more active process. And, for me, working with other people is exciting as it engages new knowledge. Most Aboriginal people would acknowledge that one person doesn't have all the answers or stories. It is incumbent upon us to get the right people involved, to seek their permission, and engage them so we can have conversations that aren't possible on our own.

Collaboration is an extension of that process, really. It enriches the exhibition and makes it more interesting than if it were just me sitting alone in a studio painting.

SADo you think about the collaborative element early in the process, when you're planning an exhibition, or does it come later when you've progressed with the work?

JJIt's usually part of the process. Because I am not from Sydney—my family's from Bathurst and Tamworth—for me to conduct any kind of cultural activities here, I have to engage properly with the local community. I sit down and talk about opportunities to bring them on board and develop projects that strengthen them.

Working with the women embroiderers from ACE in Parramatta was extraordinary: the project saw migrant women from various communities including India, Afghanistan, and Korea work on a series of plant embroideries from the Sydney area. Plants are significant to understanding where you live—knowing when they come into season and flower or fruit binds us to a place and gives us a sense of 'home'.

To engage in this knowledge, we connected the women with local elders and knowledge holders to learn local stories and histories, which created the space for people to talk. For instance, some of the Afghan ladies understood how Aboriginal people are divided into clans, each with their own language.

There were also connections in understanding the impacts of colonialism and the need to overcome it. They knew massacres. They knew the weight of colonialism on our culture. We were talking to like-minded people, which was reassuring for everyone. I think we all felt that here was a community that understood our story.

. . . we're sitting in a rich and complex present that Australia still denies and hasn't come to terms with.

For me, as an Aboriginal person, when I walk into a room, I know that everyone in that room is hostile to my history and identity—that I have to prove myself and my story. This project was one of the few times in my life I didn't feel that. It was really healing.

Many of the women said, now I understand my role in looking after country. I understand what I need to do when my family come here. I'm going to take them to these places. I'm going to show them these stories.

SAIt's interesting to hear you talk about common understandings between two quite different groups of people.

JJThat's the thing: migrants don't get the opportunity to learn about Aboriginal people. People told me that they learnt about Aboriginal culture through media coverage, which was often negative. In most instances, this was the first time they had the opportunity to sit down with Aboriginal people and have real conversations.

This is an indictment upon Australia. It doesn't seem to matter how many amazing books or films are made by Aboriginal people, we have to handhold every Australian person and walk them over the line. It's disappointing, but it seems to be the only way you start making change. It seems most Australians just don't want to do the work.

This project talks about history and the fact that Australia is blind to its rich and complex history, but also that we're sitting in a rich and complex present that Australia still denies and hasn't come to terms with. This is a living history that we need to contend with, and these women are very much part of that story. —[O]