Nari Ward

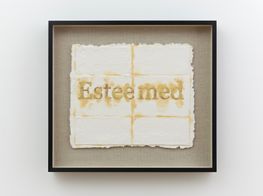

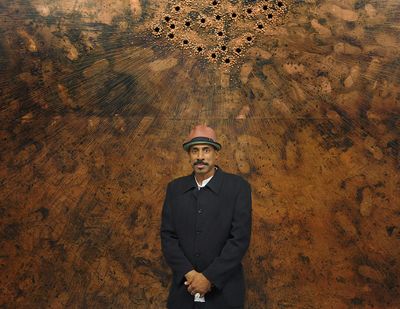

Nari Ward. Courtesy Pérez Art Museum Miami and Lehmann Maupin, New York/Hong Kong/ Seoul. Photo: World Red Eye.

Nari Ward. Courtesy Pérez Art Museum Miami and Lehmann Maupin, New York/Hong Kong/ Seoul. Photo: World Red Eye.

Nari Ward has witnessed his neighbourhood transform. Harlem, once neglected and teeming with creative energy but rampant with drugs, crime, and wreckage, has become home to organic groceries, high-end cafés, and high-income housing. It is a symptom of many gentrifying neighbourhoods in New York, whereby high-earning populations replace lower-income inhabitants. Ward has been making art and collecting the material history of a now-extinct backdrop for 25 years, working in his studio on 141st street, which was first a fire station, then a piano moving company, then the site of a limousine service.

His practice since the 1990s, when he was a young graduate from Hunter College and later Brooklyn College where he earned his MFA, has been based in found objects. He confounds these objects, extending and bringing to light their materiality, combining them by welding, burning, or binding them with rope, sugar, or soda, or sometimes just placing them inside one another in a found picture or grandfather clock. Ward's assemblages and installations are often tactile, striated with layers of history, and charged with the grit of a survivalist nature, while others are humorous, poetic, and tender.

Ward's solo exhibition, We the People, at the New Museum (13 February–26 May 2019), surveys 25 years of the artist's work: sculptures, large-scale installations, paintings, and videos created between 1992 and 2019. A large portion of the works are from the 1990s, a statement in itself, since the issues of that period—poverty, race, consumer, and material culture—still resonate today. The artist was initially inspired to title the show 'Hunger Cradle' after a 1996 work of that name: a giant web of yarn, rope, and found materials—such as piano keys, books, car parts, and hand tools—woven within. Ward made the installation at the former fire station in Harlem that would become his studio, for a show he co-organised in 1996 with his friends and fellow artists Janine Antoni and Marcel Odenbach titled 3 Legged Race. The consuming installation embodies the sites where it is shown; as he describes in conversation, the piece both devours and protects the physical remnants of these places, somewhat a metaphor for his artistic process. At the New Museum, Hunger Cradle includes remains from the building adjacent to the museum, which it acquired; a tangle of discarded objects and frozen moments piled into one another.

Ward's exhibition is a display of lived experiences and exchanges with individuals otherwise exploited and neglected by power. Amazing Grace (1993) consists of over 250 dilapidated baby strollers that Ward found abandoned on the streets, arranged around an aisle of flattened fire hoses that provide an unsteady ground to walk on. The voice of influential gospel singer Mahalia Jackson performing the hymn 'Amazing Grace' accompanies viewers as they consider the lives these strollers once had, whether they cradled children or were repurposed by the homeless to haul possessions. As a whole, Amazing Grace is a memorial to New York of the early 1990s, drawing in the state of Harlem and the devastation caused by the drugs and AIDS epidemics, while reaching back to histories of colonialism and slavery, with the hoses arranged on the floor echoing the hull of a ghost ship.

Monuments and memorials appear throughout Ward's show. Made from an iron fence overgrown with dilapidated textiles that have been caramelised to look like entrails, Sky Juice (1993) references a Jamaican drink sold by street vendors and made of ice, syrup, and water, poured in a bag and consumed with a straw. Standing on cement blocks, the fence holds a shredded sun umbrella with dangling mutilated plastic bottles filled with found photographs. The clumped textiles in the fence are coated in sugar and Tropical Fantasy soda, a soft drink originally founded in Brooklyn in 1990 that gained popularity in the poorer neighbourhoods for its 0.49 cent bottles. A rumour spread in 1991 that the company producing Tropical Fantasy Soda was lacing the soft drink with an agent that could sterilise black men. It took the city's (black) mayor at the time, David N. Dinkins, to drink a bottle on television to avert further panic.

In this conversation, Ward talks about his works from the 1990s and 2000s, reflecting on ideas and forms of power and how making work during that time feels very different to how he makes work today.

I listen as a black person, as an artist, and as a human to try and negotiate my connected-ness beyond culture.

FKYou mix very distinct cultural experiences in your work, related to, for instance, urban and civilian institutions—like the corner shop—or institutions of power, like the police or a financial bank. How do you approach and subvert the codes, languages, and signs that you bring to life in your work?

NWThese are all kinds of street power symbols. The role that I'm trying to play is about creating doubt, because these logos are all about affirming a kind of label that is supposed to be in some ways unmatched—this is what it stands for, what it encompasses. So, it's really about fracturing that perspective and thinking about all the possible grey areas that other content and narratives can occupy.

For instance, this new work that I am currently making—a take on the copper panel works, 'Breathing Panels', which I had done in 2015. I'm looking at history and figuring out the many unrepresented voices in history and how history is always evolving. To talk about that evolution isn't about showing more history, but it's to sort of hold history down and maybe even contain it. So the whole emphasis of this idea, which is tied into what you're asking, is this sense of stopping a moment, but within that moment it is not about revealing all the possible moments within it as it is about highlighting what's in it. History tells a particular story, and I'm trying to say: 'Yeah there is a particular story, but there are many stories that aren't visible within that one created narrative.' I think that it's about bringing mystery into the conversation more so than facts. So the whole idea is bringing this marker, image, or form to the forefront, but at the same time destabilising it so that it acts as a placeholder for other possibilities or somebody else's narrative.

FKCould you tell me more about the 'Breathing Circles' series (2018)?

NWThese are done in copper and they're referencing this African [Congolese] cosmogram that represents birth, life, death, and rebirth. They also served as breathing holes for runaway slaves, who hid under the floorboards at a church on the Underground Railroad: this old church is a very important site—the First African Baptist Church in Savannah, Georgia. The whole idea for me when I saw it—the magic and power of this site and these patterned holes on the floor—was that these enslaved individuals were trying to preserve their history in this very important way of resistance, which is this coded breathing hole pattern on the floor that served as a space for the basement's ventilation. In the daytime, the slaves would hide under there and at night they would go North. For me, it was really a powerful thing that was preserved and used in a radical way. I like this idea that the holes were visible and also invisible at the same time.

My challenge was that it was a really good story, but how do I make it present? What I did with the copper panels is that I started walking on top of them to bring the body back into the space. This became a series of works that had to do with the landscape and directions. I wanted to have this series deal with this idea of American history, specifically.

FKThis idea of relating to history is linked to issues of what is visible and invisible, and what one can understand or grasp from different human experiences; but it is also connected with what one cannot fathom or understand, or what is totally opaque.

NWAnd that's another way to talk about another possibility, because I think the idea of being opaque is the idea of deciding not to capitulate to the norm, because you don't necessarily need to be part of that canon—being outside of it is quite okay, and trying to be inside of it in some way dilutes your position. You fight for your own space, not to join that space. So in fighting for your own space, that means that you may need to reject that other thing. Opacity as a way of rejecting clarity, which is the history that is known—for me, that resonates.

FKCan we talk about your use of animals, such as the fox and the goat, in your work? They belong to the world of fables and mythological creatures, but they also have this pedestrian quality to them.

NWThey're also about chance. They are not entirely controllable because they're nature. Joan Jonas always has her dog in her videos. I always thought that it makes sense, because as an artist you're always trying to have this control, but then you need to figure out how to bring in this space that you can't control. That is powerful. There's a level of opacity to that life that you're negotiating, but it's also powerful to bring it in as a presence to act and react against. For me, that's really exciting—to try to draw on the live animal and the expectation or imagination to what that animal might be. For instance, the show I did at Socrates Sculpture Park, G.O.A.T., again (29 April–4 September 2017), was very much a play on the moment. The goat was a metaphor for debauchery. A metaphor for male ego; male prowess. I made Bipartition Bell (2017)—this large goat scrotum that you could walk under—it was meant to look like a bell, but when you went in to use it, it made this tiny ding rather than this big chiming sound. It was all playing on expectations and destabilising those expectations into being much more about shortcomings.

There was also the piece Apollo/poll (2017), which I'm showing at the New Museum. It was the frame for the entire show at Socrates Sculpture Park, because it talked about consensus and at the same time entertainment. I was referencing the Apollo Theater's amateur night. I have never been to the Apollo Theater, but every Wednesday they have Amateur Night, and when you think of the Apollo Theater you think about all these stars that have gone through, but you can also think of the other side of it being all the people who want to be stars. I was trying to figure out how the blinking of the Apollo sign—having the word 'poll' in it—could work. Before the election, I wanted to have the sign blink 'Apollo' / 'pollo' [Spanish for chicken] because the show was in a Spanish neighbourhood, and I wanted to be playful—and it wasn't a goat but chickens that the work was going to reference. But when it went into the poll space, it became about power in a different way, and the chicken didn't work there. That work talked about the idea of belonging in some way.

FKHas the current political atmosphere in the U.S. made its way into your studio?

NWIt does in different ways. I've had on my door, for years now, a little plastic plaque of Martin Luther King that the school in the neighbourhood had thrown out. I just had it on my door and for some reason within the last two years it sort of felt like an island. It was just an image of his head, and it made me want to bring King into the centre of the conversation again, just his presence. I was also recently listening to Cornel West talking about The Radical King (2015), and how King has been mainstreamed to being like Santa Claus in a way. But actually he was very misunderstood and, also in his own way, very conflicted in terms of the breadth of his political agenda. My desire is to re-look at his sacrifice and bring that back around for the time that we're in.

FKYour work is very formal and rooted in the exploration of materials. The found objects are also semantically coded—they bring in layers of meaning.

NWYou know I came out of a drawing background. I'm a formalist. Sculpture didn't come to me until the end of grad school with my thesis show, which was an installation. But prior to that, I was doing drawings. It was more about the line or the rectangle or the square, balance and compositions, space and gesture. This and being haunted by the history of the medium kind of made me want to say: how do I think about this moment? I think that's when using found objects made most sense as it was so much about being in the present moment with the viewer. And also, it was a challenge to retell the narrative of the object in a way that a line wouldn't be able to convey.

FKThis makes me think about the work Amazing Grace (1993). To me, the installation employs the readymade as a tie to a record—the marker of a social practice with a documentary component.

NWWhen I think of artists that work with found objects, such as The Heidelberg Project in Detroit, they're all reacting to some event—the breakdown of the urban environment or the rebellion of L.A.—and so they're from that residue. They're trying to reconstruct different narratives that happened. Because of the show, I've been reflecting a lot on the work I did in the nineties, and how I could never do it now because it was so much about the state of things at that moment. It really is kind of like you said: a documentary iteration of material.

The one material that was so ubiquitous and so dangerous that I did not touch because it was so charged was the crack vial. It was everywhere, almost like pebbles. Because it was such a devastating epidemic, I did not feel I could address it at the time. But I do think about those vials and what having collected them would mean today, as they were so much about what they represented in terms of loss, but also in terms of greed. There's a whole narrative that considers that this was a kind of expulsion to clear out the inner cities for what's happening now with gentrification, because immediately after this happened the government stepped in and created empowerment zones where they dictated who was going to develop these neighbourhoods. It was almost like dropping a bomb on these poor neighbourhoods and then going back in and reforming it, all within 20 years. It really makes you think about the other narrative that is not in the mainstream, and it still seems to somehow resonate today.

FKHow has this aspect of social documentation evolved for you throughout the years?

NWI still walk around and react to things that I see, that I pick up on the street; but it's much more driven by the anxiety of the news—thinking about stuff and trying to figure out what I need and what's going to help tell the story. Now I can go on eBay and figure out how to get those things I'm thinking of. It's just a different way of engaging with ideas and materials; I can be as specific as I want when looking for a particular material.

There was a time, being a found object artist in a more overlooked urban space, that you would find things that would be on the street for two to three weeks. Now things disappear in the same week. You have to be quick now. All of the strollers [in Amazing Grace] were found. I was an artist in residence at the Studio Museum at the time, and for a good three to four months, I would just walk around. They weren't that hard to find. People were using them and would abandon them, or they were using them for bottles and cans. They would congregate in the empty lot and then go to the store and get their deposit.

There were all these remnants of that history in the building. It was relatively clean but there was stuff in the basement, and I decided that I wanted to lift everything off the ground and basically weave it all together.

FKYou have been working in Harlem for a very long time, and have seen and experienced a lot. I am curious about how emergent themes of the nineties such as institutional critique and identity politics sit in your work. How has the discourse changed?

NWI think it was always the idea of fixating on otherness as being a fight—like I'm going to fight to declare my space—and I think there's much more an inquiry now as things have evolved from questioning what 'belonging' might mean. I think there is that double clarity of looking at the fiction of the system and discrediting it—the structure that has declared you as the other. At least my own evolution has come to that.

Now I see it as, 'Oh, there are a lot of lies and those lies have become institutionalised.' So, I think that woke moment is underlined by our current situation. The Obama moment made you think that it's all good, progress is happening; so I kind of chose to ignore the backsliding of history, and the indiscretions that happened. But I realise that those are not indiscretions; they're just a symptom of the lies that have been perpetuated from the very beginning. That realisation has kind of made me listen and have this double consciousness. I listen as a black person, as an artist, and as a human to try and negotiate my connected-ness beyond culture. I feel like that's where I'm at and where we are right now.

FKCan you tell me about Hunger Cradle (1996)?

NWHunger Cradle was first shown here in my studio at a show called 3 Legged Race, with fellow artists and friends Janine Antoni and Marcel Odenbach. I took the second floor, Janine was on the top floor, and Marcel on this floor with a video projection. Basically, I collected elements from the life of the building. It's a building from 1916, a horse and buggy building. It then belonged to the fire department, and then it became a piano moving company, and then it became a limousine service. There were all these remnants of that history in the building. It was relatively clean but there was stuff in the basement, and I decided that I wanted to lift everything off the ground and basically weave it all together.

I had just come back from a Shaker residency and I did this bottle quilt project. It was really labour-intensive. I found these bottles that were from a dumpsite. They were all different kinds of bottles. The best way to weave them was to cover each one with yarn and tie them all together, so it was hours of work. I had this bottle curtain that I wanted to present, and I thought I could do this with other objects. So, the entire cradle—and cradle is a key word—talked about the idea of devouring but also protection; it is a correlation and opposition of those two things.

The piece was purchased, and in a moment of crisis it tested my artistic integrity. Does it make sense to sell this piece from this space in Harlem? What does it mean if it goes off to another place? I decided that it would function only if something is added to the work within every new context, so it almost absorbs another element of its own history. At the New Museum, there were different things I had to look at: two metal trusses that the museum uses to hang things from the ceiling, a super 8 film projector and parts of a paper copier, and also the old radiators that were there in the old building next door that's just been acquired by the museum.

FKSuper Stud Salt Table (1995/2019) is a piece that was recreated for the show. Could you talk about it?

NWIt is a cod fish table that has a display of book pages around it that I appropriated from a book about the collection of Robert Lehman—a collector with a wing at the Met. To acquire his collection, the Met had to recreate his house, so if you go into the Robert Lehman Wing you go into a recreation of his house. What a demonstration of power!

When I was able to appropriate the book from his collection, I decided I wanted to talk about power in my own way. The book is laid out with images of the collection and their provenance. I took out all the pages with the Madonna and Child and I made this piece called Super Stud (1995–2001). It was a metal house made out of metal studs and had the pages—from the book I had—framed around the walls of the house. The floor was covered in cod fish, so you had to walk on salted cod fish. It looks like you're walking on a granite floor, but when you look down you see the little fins. And the ceiling was made out of plantains. It was a full-on experience with the images of Christ inside.

FKCan you tell me more about the cod fish and the plantains?

NWCod fish is something I really grew up with. Ackee and salt fish is Jamaica's national dish. So there's a personal component to it, but cod fish is also what allowed for European conquest of the so-called New World. Without the preserved fish, the Vikings wouldn't have been able to do their trans-Atlantic treks, so it was the staple that really allowed for the mind space to go out and conquer. And there is the relation to Aquarius, the fish, the symbol of Christ. So, there were all these pieces that were tied into the work. The plantains are just phallic. I thought they'd decay and get smelly and soft after painting them, but I coated them with a gel medium when they were green and so they hardened. They were kind of preserved.

FKYour works also preserve histories in a way that is both concealing and revealing.

NWLike Anchoring Escapement; Fang (2018): the grandfather clock that has the cosmogram pattern at the top, and two African statues are placed where the pendulum would be. They are on display but also sort of hiding. It is kind of replaying the narrative of the church. But also for me, what's exciting as a sculptor when thinking of the history of vitrines and how the sculptures contained within them refer to the ethnographic museum, is that it's a kind of vitrine that everyone is familiar with. It is an element of time with its pendulum missing and what replaces it is this other element of time in there instead. —[O]