Tomoko Yoneda: Confronting History

ShugoArts | Sponsored Content

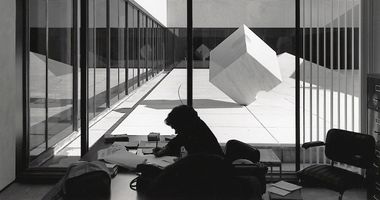

Tomoko Yoneda. Photo: Tomi Räisänen.

Tomoko Yoneda. Photo: Tomi Räisänen.

Tomoko Yoneda's practice is centred on photographing sites saturated with memories of the past. Implications of violence run throughout Yoneda's work, be it political conflicts, war, and even natural disasters, though they are hardly visible in her serene compositions.

Yoneda's longstanding concern with traces of the past can be found as early as 1996, when she captured heat stains on wallpaper in 'Topographical Analogies'. Taken inside abandoned apartments in London, where she had been living since 1989, when she began her MA in Photography at the Royal College of Art, the black-and-white photographs reveal little about the lives of previous occupants, except that they once existed.

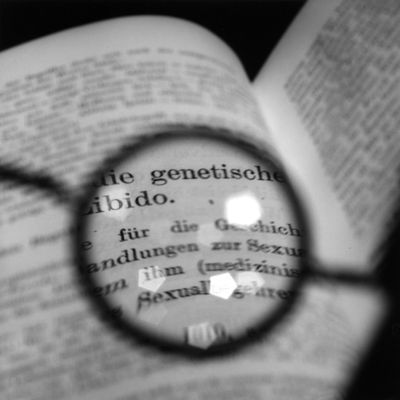

After 'Topographical Analogies', Yoneda continued to uncover layered histories through specific individuals as well as geographic locations. In her series 'Between Visible and Invisible', for instance, the artist photographed spectacles belonging to 20th-century intellectual figures such as Sigmund Freud, Bertolt Brecht, and James Joyce, capturing a segment of text through the glasses that was significant to that individual.

In Trotsky's Glasses—Viewing a dictionary that was damaged in the first assassination attempt on his life, for instance, we are given a material glimpse into a seminal moment in Trotsky's life. The works' titles are also used to further the unseen influences of each text, as in the case of Freud's Glasses—Viewing a text by Jung II.

Each of Yoneda's series involves a significant body of research, particularly when the artist is engaging with a new context. Ongoing since 2000, her series 'Scene', for instance, focuses on locations of historical violence. With each engagement, Yoneda reads into local history, studies old photographs and illustrations of the place, and interviews residents.

The charge of the events that occurred in the places she captures has often been replaced with peace and banality by the time Yoneda arrives there, resulting in images of tranquil urban and natural landscapes.

Take the image of a busy beach from 2002, for example, shot on a clear day, the blue horizon extending indefinitely into the distance. It is the title that reveals its past, the particular event that led Yoneda to the site: Beach—Location of the D-Day Normandy Landings, Sword Beach, France.

The chilling effect reverberates across Yoneda's other works, such as the view of a small pathway under another blue sky with the title Path—Path to the Cliff Where Japanese Committed Suicide After the American Landing of WWII, Saipan (2003).

It is the disconnect between the peacefulness of Yoneda's images and the brutal histories imparted by her titles that insist on the duality of violence, equating these events with everyday banality.

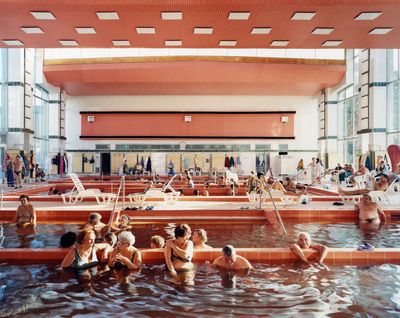

In 2009, after having focused on Estonia and Hungary ('After the Thaw', 2004) and Bangladesh ('Rivers Become Ocean', 2008), among others, Yoneda turned to examine Japan's recent history. The five projects that followed concern the indirect or direct impacts of Imperial Japan on its neighbouring countries and itself.

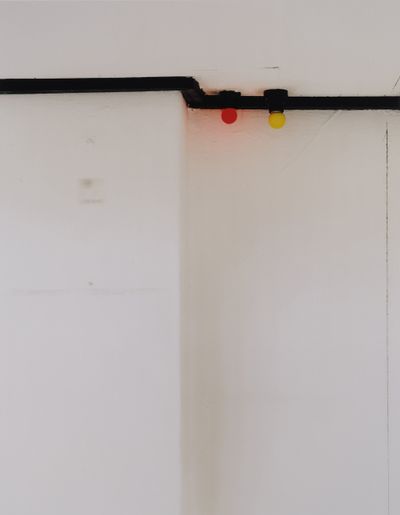

The series 'Kimusa' (2009) features the interiors of the eponymous building in Seoul, formerly home to the headquarters of South Korea's Defense Security Command that was infamous during the military regime and in its aftermath for allegations of torture against protesters and political dissidents. Vacant rooms also recur throughout 'Japanese House' (2010), which concentrates on the early 20th-century houses built in Taiwan under Japanese occupation.

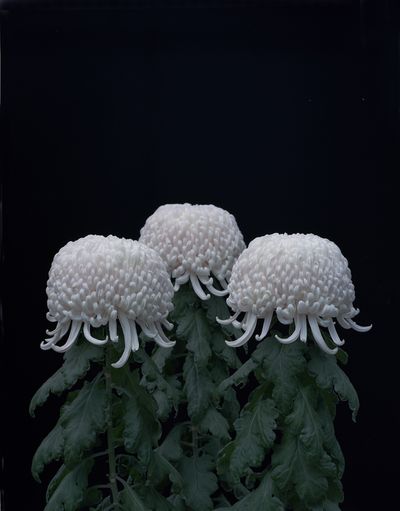

Yoneda returned directly to Japan in 'Cumulus' (2011–2012), capturing the Hiroshima Peace Day on a cloudy 6 August, alongside an evacuated village in Fukushima. Three white chrysanthemums bloom against black in Chrysanthemums (2011)—a sombre sight of flowers that are associated with both death (commonly appearing at funerals) and the Imperial Family of Japan, representing the Family crest. The flowers stand firm and powerful yet fragile, as if they are a portrait of a family facing the aftermath of the Japan earthquake and tsunami of 2011.

Much of Yoneda's work is inspired by literature, as in the case of 'The Island of Sakhalin' (2012), which departs from Anton Chekhov's investigative piece Sakhalin Island (1893), reporting on the Russian island north of Japan. Yoneda was drawn to the island's intersecting histories, including those of the Indigenous population, the arrival of Russian criminals and political prisoners that were sent to the penal colony, as well as the border that once existed between Japan and Russia, splitting at the 50th Parallel, with South Sakhalin being administered by Japan until 1945.

A collection of photographs by Yoneda from the past two decades is currently on view at ShugoArts, Tokyo (4 June–9 July 2022). Titled Echoes—Crashing waves, it is her second solo show with the gallery following Dialogue with A.C. (2019), which saw Yoneda travel from Algiers to France, visiting key sites in the life of French philosopher and author Albert Camus.

Echoes also succeeds the artist's major solo exhibition at Fundación MAPFRE in Madrid last year, which included a newly commissioned series on the Spanish Civil War. In this conversation, Yoneda shares her approach to drawing the past into the present in her photographic practice.

SPCould you begin by introducing your exhibition at ShugoArts? Where does the title Echoes—Crashing waves come from?

TYThere was a social activist called Ayako Ishigaki who moved to the United States in the 1930s, when Japan was moving towards militarism. She participated in the peace movement and worked at the Intelligence Bureau of the United States Office of War Information during World War II, though was deported to Japan after the war as a result of McCarthyism.

In 1940, Ishigaki published what could be regarded as an autobiographical memoir of sorts, under the pseudonym of Haru Matsui, titled Restless Wave: My Life in Two Worlds. In it, she expresses the anguished experience of living between the United States and Japan, as well as her anti-war sentiments.

The constant waves of violence, crisis of humanism, thirst for peace, and anti-war feelings that she felt during World War II—as conveyed through the book's title—serve as the outline of my exhibition.

The title, Echo—Crashing waves, reflects the repetitive waves caused by the echoes of violence, which not only Ishigaki, but I too wish to question. It illustrates and attempts to challenge the current circumstances of the world.

The Covid-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and various other conflicts shaking our world have served to highlight that history is indeed a living thing.

SPEach of your photographic projects begins with extensive research into the local history of the sites you engage with. Do you photograph over extended periods or is it more focused?

TYThe research involves resources spanning books, old newspapers, photographs, films, artworks, libraries, international archives, the internet of course, and directly interviewing people involved. Once I feel I have understood the subject both historically and philosophically, only then do I go to the location or archive to photograph.

That experience is also an important factor in the work and affects the process. So the people I meet, the emotional feel of the place, and what I see as an observer when I get there is an all-important part of defining the final work.

When visiting the actual locations to take photographs on-site, most of the time I'm fully prepared and determined to go ahead with the photographing regardless of the circumstances. Whether or not the weather is bad, I set up my large-format camera and tripod.

I think this tension is important. This is because the place, the events that unfold there, and its memories are always present at any time. It is important to have a sense of tension, to concentrate one's energy, and confront that very moment.

SPHow do you know when you are 'done' with a place—is there ever a feeling of completion or closure, that you have spent enough time with it?

TYIt's more or less intuitive. I take photographs while striving towards a particular goal, just like a competing athlete. I can determine then and there whether I've reached a definitive completion in terms of the act of physically pressing the shutter, and in terms of capturing the image.

Since I mostly work with large-format cameras, there is a limit to the number of films that I can decide in advance to take with me. Pressing the shutter involves as much preparation, tension, and determination as arriving at the starting line of a race.

Ultimately, it is not complete until I've finished the entire developing and printing process. The only time I gain a sense of completion or closure is when I'm done with everything, including assigning captions to the photographs, since I consider the titles of each series to be extremely important as well.

SPYou photographed the areas in 'A Decade After' twice, first in 1995 and then in 2004, when the latter was commissioned by the Ashiya City Museum of Art for the 10th anniversary of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. Could you talk about the changes you observed, whether in terms of your practice and approach to locations or the sites themselves?

TYI returned to my family home three months after the earthquake happened in 1995. The situation in Japan was still chaotic. I took these photographs while walking the streets of my hometown of Hanshin with local friends.

The area had suffered the effects of the earthquake, and everything was completely devastated. It had become a place where the terrifying and destructive powers of nature, and its sheer ability to engulf the city, its inhabitants, and everyday life in a mere instant, were in chaotic amalgam with various individual memories.

I took these black-and-white photographs at the time and preserved them as a personal record, and having consulted with the curator, later decided to revisit and include them in my 2005 solo exhibition A Decade After.

The buildings, roads, and infrastructure that I photographed in 2004 for the 2005 exhibition had been reconstructed and restored in the wake of the disaster.

I believe that the importance of art lies in its ability to inform us of the outrage of war that is once again shaking our current times.

Prior to the earthquake, the homes had each marked the passage of time, harboured various memories, and were rich in character from the families that lived there. Afterwards, they were all uniformly rebuilt. It almost looked like a housing exhibition.

From place to place, there were vacant lots where homes were missing or gardens overgrown like jungles. Such were the results of disputes between the public administration and the newly reorganised land, or the owners of some homes having died in the earthquake, or not having returned after evacuation. While on the surface everything seemed to be in order, an array of issues were yet to be resolved.

The classroom that was to be demolished had served as a temporary mortuary. Temporary housing had been built across various parts of the city, including places along the river and in parks. Restoration housing for those who lost their families and homes were relocated far away from the communities where they originally lived.

The city itself superficially heralded the success of its reconstruction efforts, yet while it remains unseen or overlooked, there are indeed people who still require help and emotional support. I felt that those unseen scars should not stay hidden and should never be forgotten.

SPWhile consistently working with historical sites, between 2009 and 2015 you concentrated on buildings and areas in the Korean peninsula, Japan, Taiwan, and Russia with echoes of Japan's imperial past. Another seven years have passed since the last series in the project, 'DMZ' (2015).

How do you see Japan's relationship with its neighbours and recent history now? What has changed for you? What remains the same?

TYThanks to technology, all manner of information can be easily obtained. The relationship between Japan, Asia, and the world has certainly become one in which we can engage in a transparent dialogue with one another, on a personal level, and beyond national borders, as it should be.

On the other hand, physical interaction between human beings is becoming sparse, placing us at risk of being used for acts of violence or influenced by propaganda. The Covid-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and various other conflicts shaking our world have served to highlight that history is indeed a living thing. The rulers of the times have taken away the power of the individual. Peace is something that is extremely fragile and difficult to maintain.

History has been geopolitically used by rulers, sacrificed many lives, spun out of control, and has become fragmented. The tension in the world has certainly increased again, just like in the era of violence that Japan has traced in the past.

My work brings to light the lives and presences of people who reside within hidden realms and serves to raise awareness for issues that they confront. I believe that the importance of art lies in its ability to inform us of the outrage of war that is once again shaking our current times, and to bring about a significant impact on people and the world as a whole.

Drawing connections between the past and present guides us towards rebirth and hope, and also warns us of the ephemeral nature of peace. It is still extremely difficult to talk about memories of war. I know it is not a simple thing to say, but pain and memory should be detached from politics.

Everything can be politicised, of course, but we are all human to start with. We should find a way to be open to solidarity and understanding the pains of others from the past to understand what those around us are experiencing now, and if we are not careful, what we will all experience.

SPCould you elaborate on the relationship between image and text in your works? You've said elsewhere that captions are indispensable to them. In turn, what can images do that text cannot? Can they, as text does to them, influence the way we think about the written language?

TYThe captions contain minimal information. Text is a symbolisation of image, and strictly speaking, the images that emerge from text can only be understood by looking into the minds of each individual who reads them.

Drawing connections between the past and present guides us towards rebirth and hope, and also warns us of the ephemeral nature of peace.

On the other hand, something that is apparently visual, in this case, photography, comes into one's field of view more directly and serves to stir our visual perception and emotions. What I value are the different images that viewers conceive through the overall relationship between text and image, between what is seen and not seen, and the various dialogues that emerge as a result.

The environment in which one was born and raised, as well as gender, nationality, and religious views, all differ between viewers. In attempting to present various issues and highlight the fragility of human existence, I consider the narrative to begin with each viewer.

A site or an event in which something took place does not necessarily have to be dramatic. It may be familiar, while at the same time harbouring certain elements of risk or danger.

SPI imagine part of a viewer's experience of your work depends on their knowledge of the site, whether they were familiar with its history or encountered it new through the captions. What have been some memorable responses to your photographs as a creator?

TYThere are of course some viewers who may not be familiar with the themes and subjects raised within my work. Nevertheless, I hope that through it, viewers can catch onto or develop an interest in certain chapters within modern history, and ask themselves why I, as an artist, am creating work that is tied to such sites and events.

In doing so, I hope that it would lead them to question and respond to the events of our current era, and thus generate some kind of dialogue. History is not far from the past. It is connected linearly, and what is happening right now leads to the future.

I think that each person must open their eyes and critically assess the present. There are still certain memories that cannot be publicly disclosed, and I feel that, as an outsider, I can open another door by presenting these memories through my work. I hope that my work, like a stone thrown into a pond, can cause a stir and encourage someone to stop and think.

SPAt your recent exhibition in Madrid, you were commissioned to create a new body of works concerning the Spanish Civil War. Could you discuss the resulting series? How was it different from photographing elsewhere in Europe?

TYThe Spanish Civil War had a great impact on the world. It was also a war that influenced 20th-century art from end-to-end, as people throughout the world volunteered to take part in the battle, including various artists, writers, and intellectuals who would later become leaders.

Since I have been interested in it for quite a while, I have read various documents and written accounts and met with researchers and historians. I proposed creating a body of works concerning the Spanish Civil War for the exhibition at Fundación MAPFRE and gained the opportunity to take a series of photographs.

I had initially anticipated researching and taking photographs across North and South America, yet I had to abandon these plans due to the pandemic. I therefore ended up photographing only in Spain. In Spain, I felt that there was still some impenetrable wall in terms of discussing the history of the civil war that had claimed many victims.

In a sense, I felt that being a foreigner gave me a little freedom to touch upon this war. Even in Japan, the history of war is still a very sensitive subject. Sometimes such a topic is rejected altogether or can result in breaking off conversations.

However, to know the past and to understand the kinds of experiences people have undergone that lead to the present, it is necessary for us to also confront various histories. It is impossible to confine historical events to darkness.

I travelled from the Sierra Nevada to Jarama and Brunete, which were both battlefields of the Spanish Civil War. I learned that from Japan, a cook named Jack Shirai participated in the United States Abraham Lincoln Brigade, and Oliver Law, one of the commanders of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, had become the first African American to serve as its commander.

These two individuals both fought in Jarma and lost their lives in the Battle of Brunete. I also photographed some of the personal effects of the Andalusian poet and playwright Federico García Lorca, who had been killed by nationalist soldiers.

I was not even sure of what still existed. Lorca's life and death signify the weight of loss and tragedy of this extraordinary human being whose life was taken away for no reason. Through the physical materials he left behind, his warmth can still be felt. I wanted to photograph them straight on, without fantasy.

Titled 'The Sleep of Apples' in reference to a phrase from one of Lorca's poems, I presented the photographs of these landscapes and objects together in the exhibition.

SPWhat are you researching at the moment?

TYI cannot share much information at this point, but I intend to continue engaging with themes such as human existence and suffering, the denial of violence, wishes for peace, and love. Having said that, I am doing some research in the hope to explore new means for expressing and communicating these themes. —[O]