Ishiuchi Miyako: Photography as Psychological Event

Ishiuchi Miyako. Photo: © Maki Ishii.

Ishiuchi Miyako. Photo: © Maki Ishii.

On 8 December 2019, curators Natalie King and Yuri Yamada travelled to the outskirts of Tokyo by train to visit renowned Japanese artist Ishuichi Miyako in her home studio in the suburb of Gunma.

At Ishiuchi's light-filled home studio with silver walls and an exterior rendered in black wood, they gathered around Ishiuchi's large table, perusing books from her vast library and discussing King and Yamada's co-curation of the exhibition Reversible Destiny: Australian and Japanese Photography at Tokyo Photographic Art Museum (TOP, 24 August–31 October 2021).

As the premier photography museum in Japan devoted to photography, King and Yamada conceptualised the notion of looking backwards and forwards to imagine collective futures, and an online symposium will take place from 15 to 17 October 2021.

What does it mean to make a photograph now, in a time of global upheaval, human fragility, and uncertain futures? How is contemporary photography entangled with the past, halted in the present, and imagining the future?

King and Yamada have curated eight artists from Australia and Japan in Reversible Destiny, exploring the uncanny ability of photography to collapse time and merge yesterday, today, and tomorrow. They include: Maree Clarke, Rosemary Laing, Polixeni Papapetrou, Val Wens, Katayama Mari, Hatakeyama Naoya, and Yokomizo Shizuka.

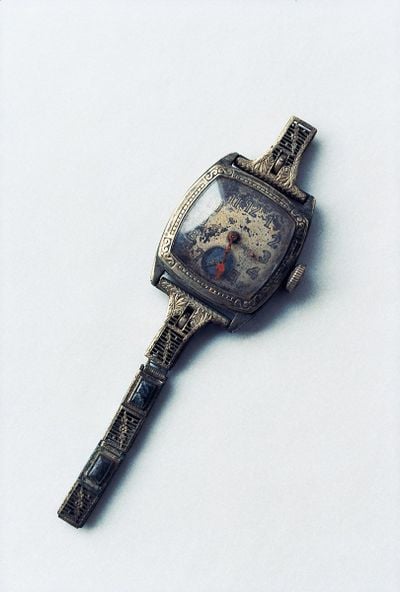

Ishiuchi's contribution is her ongoing series 'ひろしま / hiroshima', commenced in 2007, whereby she makes an annual pilgrimage to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum to photograph belongings and clothing left behind by those who perished in the devastating nuclear attack of 1945. With tenderness, she photographs items left behind imbued with memories and loss.

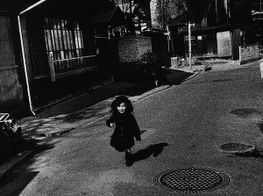

A self-taught photographer, Ishiuchi initially studied design and weaving at Tama Art University in Tokyo. Raised in Yokosuka, the site of the largest overseas U.S. naval base, Ishiuchi has been attuned to her military surroundings.

In the series 'ひろしま / hiroshima', she photographs garments of trauma as an ongoing act of preservation: 'I took photographs as if filling in the vacant spaces created by loss. And I felt the sadness that brings atonement.'

Through such acts, Ishuichi brings garments into the present, as with Garments of Life – Hyakutoku & Semamori, her solo exhibition with Kamakura Gallery (5 November–18 December 2016) comprising 20 photographs of children's kimonos from the Edo period to early Showa era.

Due to the challenges of rearing children during this time, special needlework on the back of kimonos acted as charms to protect them against ill health and other dangers. Later cast aside, the garments are brought back to life by Ishuichi in her photographs, commemorating the existence of both those who wore them and those who crafted them.

Ishiuchi is indomitable and notably represented Japan at the Venice Biennale in 2005 with her haunting series 'Mother's' (2000–2005). Created after the passing of her mother, the series captures maternal love, ambivalence, and loss. She won the prestigious Hasselblad Award and has exhibited at the Getty Museum, Los Angeles and the Yokohama Museum of Art, amongst others.

Delayed by one year due to Covid-19, Reversible Destiny has finally been realised as part of the Tokyo Tokyo Festival for the Tokyo Olympics Cultural Olympiad. Despite the constraints of working remotely across borders, time zones, and communities, King and Yamada curated from various states of lockdown in Melbourne while Yamada was ensconced at TOP.

Together, the curators stayed connected, finding a new modality of pandemic curation, working collaboratively from afar and conversing with Ishiuchi, finding time to pause and reflect on her practice, early training in textiles and its correlation with photography, and the meaning of now.

NK & YYWhat inspired you to take up photography?

MIA friend left some darkroom equipment and a camera with me, and I decided to try them out. The first time I stepped into the darkroom, I found the smell very familiar.

As a student, I'd studied textiles and we'd used glacial acetic acid to fix colours as part of the dyeing process. The fact that the same chemical was used in the stop bath gave me the idea that photography is a kind of dyeing, and that piqued my interest.

NK & YYWhat have been some of your early childhood influences?

MIWhen I was in primary school, I became obsessed with cactuses after watching the Disney film The Living Desert (1953). To this day, I still keep many cactuses, which I also photograph.

There's a limit to the amount of time we're alive for, but possessions have a value that is more precious and sublime. They continue to exist, oriented towards the future as presences that are nigh on eternal.

NK & YYCan you describe growing up in Kiryu and Yokosuka?

MIMy first memory is from when I was four years old, of a bridge I'd just crossed. I lived in Kiryu until I was six, and then moved to Yokosuka to start primary school—I moved from an area with no sea, to a seaside city.

Yokosuka is home to the biggest U.S. naval base in the East, and it's surprising to see the national border there, in the middle of the city. I remained in Yokosuka until I was 19. The scars of adolescence that I sustained there had a big effect on me, and you could say that Yokosuka was the starting point for my photography.

NK & YYWe were lucky to visit your home studio in Gunma, on the outskirts of Tokyo, in December 2019. Can you elaborate on your working methods and studio environment? What is a typical day?

MII don't take photographs every day, so what a typical day looks like varies from month to month. About twice a month I take a trip to Tokyo and stay for three nights or so, getting prints made of my work and going to see the exhibitions that interest me.

In Kiryu, I spend the mornings writing replies to letters, making selections from my photographs, and carrying out administrative tasks. In the afternoon, I go shopping at the nearby supermarket, and also have meetings and do interviews.

Whenever I have the time, I read. I basically take my photographs once a year, in Hiroshima. If I'm in the mood, then I also take snaps of the neighbourhood in Kiryu.

NK & YYYour work has a tenderness and sensitivity to materials. How is texture and fabric part of your photographic composition?

MII studied textiles and so I would dye white thread and weave it into cloth using a loom, according to the design I'd created. Maybe that kind of sensibility has transferred into a sense of texture in my photography.

I feel as though the grains of the photograph are like the points where the warp and the weft overlap. In my early monochrome prints, I would cut up rolls of photographic paper measuring 20 metres in length and print on that.

That 35mm photographic paper, where the grains were clearly visible, had a fabric-like quality to me. As a student, I learned graphic design for a year, so I understand the basics of photographic composition.

NK & YYFrom your debut work 'Yokosuka Story' (1977) to your ongoing 'ひろしま / hiroshima', each of your works seem deeply related to your life. You originally studied dyeing before becoming a photographer. Can you talk about what you think only photography can do and what dyeing and photography have in common?

MIWith the work I do that's driven by my own personal concerns, I'm attempting to show photographically the feelings, sensations, love, hate, and pain of adolescence, all of which have emerged from my environment.

I can't photograph the past, but I felt that I could grasp at the threads of memory that exist within the present before my eyes. That's the task of the darkroom.

Being alone in the darkroom and standing in front of these large pieces of photographic paper is both a physical and a psychological event. The result of that event is the photograph—a conglomeration of grains—that comes into being.

The image first takes shape through light and is then fixed by light, moving from negative to positive—the whole process is a delightful one for me. Both photography and dyeing are watery processes involving the same chemical fluid.

NK & YYYou have photographed personal belongings in your works such as 'Mother's', 'ひろしま / hiroshima', and 'Frida by Ishiuchi' (2013). What made you decide to photograph personal belongings, and what are the differences in the way you face the belongings in each series?

MII first started photographing personal items after my mother's death. My mother died leaving all her belongings behind, and I began photographing them as a way of conversing with her.

Everything has a history; an accumulation of time that has led up to this point. I shoot my subjects with an awareness of all the things making up their visible surfaces.

With 'Mother's', I debated whether it was okay to make these personal items of my mother into objects of public viewing, but then I was asked to exhibit in the Venice Biennale, and I said to my absent mother, 'Let's go to Venice together.' So I displayed her things at the Japanese Pavilion.

The 'Mother's' series then led to 'ひろしま/hiroshima' and 'Frida by Ishiuchi', so it was as if my mother had invited me to Hiroshima and Mexico.

Both 'Mother's' and 'Frida by Ishiuchi' portray the possessions of a single woman, but that's not the case for 'ひろしま / hiroshima'—those are the possessions of tens of thousands of nameless victims of the atomic bomb.

There are still people who went missing on that day and whose whereabouts were never discovered, and even this year, new personal effects are donated to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The things left behind by someone exist in order to pass on a message, like a kind of proof. They are not fated to become something from the past.

NK & YYFor a long time you have been trying to capture invisible things like time, memory, and life. Your works are not only about what is on the image, but also what is behind the image. Are you aware of the stories behind your photographs when you photograph them?

MII think that photography can be used to express invisible things like air, feelings, smells, sounds, and time. Behind the surface of every photographic subject lies a certain depth. Everything has a history; an accumulation of time that has led up to this point. I shoot my subjects with an awareness of all the things making up their visible surfaces.

Photographs only capture distance—a psychological and an actual distance from myself, the photographer. A photograph is fixed in an interval that's faster than the blink of an eye. It brings about on paper a world of light and shadow that is invisible to the naked eye—that we miss out on seeing or overlook. There's something very beautiful about that precarity to me.

NK & YYIt has been 14 years since you started the project 'ひろしま / hiroshima'. Has your relationship with Hiroshima changed over the years, or has your awareness of photographing changed?

MII was asked to work on 'ひろしま / hiroshima' by an editor who saw an exhibition of my series 'Mother's'. After shooting for a year, I released a collection of photographs, and put on an exhibition at Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art—that was where the project was intended to end. But then I found out that every year, new possessions are donated to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

I was very taken aback by this, and it made me feel that nothing had really changed in Hiroshima since the end of the war. From that point on, I have travelled back to Hiroshima every year, of my own volition.

My thoughts about the photography that I do there hasn't changed in the 14 years I've been doing it. I'm aware that I have no choice but to contemplate the actual situation of these people, who have been made to shoulder the history of the war in the form of the atomic bomb, from the standpoint of someone who didn't experience that herself.

After visiting for so long, events there have ceased to seem to me like other people's business, and when I take photographs of the dresses, blouses, the girls' school uniform that I myself might have been wearing on 6 August 1945 if I were in Hiroshima, I feel these things are exposed to new light, and brought back to life in some way.

The possessions become photographs through sharing the same space and time as me. There's a limit to the amount of time we're alive for, but possessions have a value that is more precious and sublime. They continue to exist, oriented towards the future as presences that are nigh on eternal. —[O]