Isamu Noguchi’s Life and Art Unfolds Like a Landscape

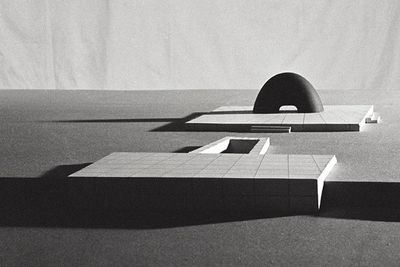

Isamu Noguchi, Sunken Garden for Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library (1960–1964). Exterior design with Imperial Danby marble. Courtesy The Noguchi Museum Archives. © INFGM / ARS – DACS /ESTO. Photo: Ezra Stoller.

Of all the 20th century's modern giants, the mercurial and transdisciplinary Isamu Noguchi was among the most unique.

And not just because of his voluntary internment in one of the U.S. government camps set up to detain people of Japanese descent after the Pearl Harbour attack—a history tracked in the Noguchi Museum's 2017 show Self-Interned, 1942: Noguchi in Poston War Relocation Center.

In London, two shows form a landscape of works that encompass Noguchi's expansive practice. The point of connection is Duo and Mountains Forming (1982–1983), two hot-dipped galvanised steel sculptures of interlocking folded sheets; the former a tall column, the latter a tectonic intersection.

Both appear in the Barbican survey Noguchi (30 September 2021–23 January 2022)—set to travel to Museum Ludwig, Cologne; Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern; and LaM, Lille.

Editions of each will complete a set of 26 steel works shown together for the first time since 1984 in A New Nature at White Cube Bermondsey (4 February–3 April 2022), alongside a re-staging of a site-specific lobby-installation in New York that was permanently removed in 2020 and is seeking a new home. Thus extending the Barbican's scope into the future, where Noguchi often felt his audience resided.

Born in 1904 to Japanese poet Yone Noguchi and American editor Léonie Gilmour, Noguchi moved to Japan in 1907 with his mother, where he learned traditional woodworking, later returning to the U.S. in 1918 for boarding school.

In 1923, he became a premedical student at Columbia University in New York after spending a summer apprenticing with Gutzon Borglum, best known for sculpting Mount Rushmore. Evening classes with sculptor Onorio Ruotolo, the 'Rodin of Little Italy', followed in 1924, prompting him to abandon academia for academic sculpture, in which he excelled.

Noguchi supported himself by making portrait busts, a practice he called 'headbusting'. Among more than 150 works amassed for Noguchi is a 1947 bronze of Tara Pandit, niece of India's first prime minister Nehru, and a 1950 bust of Indonesia's first president Sukarno.

A 1926 bronze mask of Japanese modern dancer Michio Itō, with its dramatic lock of long black hair for a handhold, marked Noguchi's first theatre commission: Noh-inspired masks for Ito's interpretation of W.B. Yeats's At the Hawk's Well (1917).

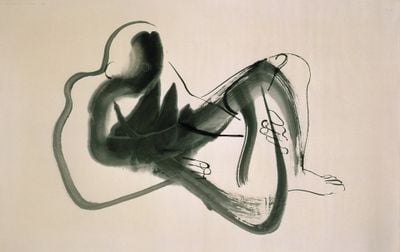

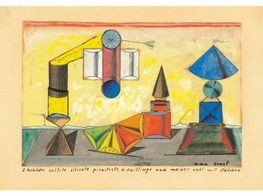

Noguchi went on to develop a long collaboration with dancer and choreographer Martha Graham, starting with Frontier in 1935, a recording of which is screened in Noguchi alongside footage of Herodiade (Mirror Before Me) in 1944, the year Noguchi produced a chess set for a show co-organised by Marcel Duchamp and Max Ernst at Julien Levy Gallery in NYC.

One notable 1929 bust depicts Noguchi's lifelong friend Buckminster Fuller, designer of the geodesic dome, in chrome-plated bronze: a material articulation of a futurist whose utopian-yet-pragmatic interest in planetary design inspired the American counterculture magazine Whole Earth Catalog.

'Your ideas were an abstraction which I could accept as being part of life and useful', Noguchi told Fuller; they met in 1929, 'when he was in revolt against' Brancusi's 'aesthetic divorce from life.'1

Yet, it was a 1926 Brancusi exhibition that triggered Noguchi's turn to modernism. He travelled to Paris on a Guggenheim Fellowship and by 1927 was working for Brancusi himself.

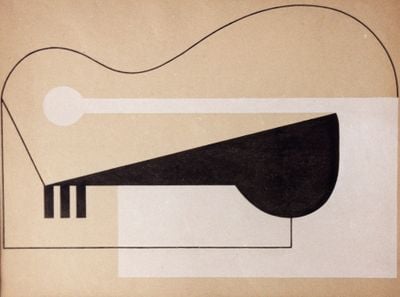

Sculptures from that time demonstrate a total departure from classical figuration. The voluminous brass Globular (1928), whose two-dimensional likeness is mapped in the gouache on paper 'Paris Abstractions' series (1927–1928), appears like a less phallic version of Brancusi's Princess X.

His desire to 'view nature through nature's eyes' gave Noguchi's sculptures a profound sense of post-human empathy.

While Positional Shape (1928) folds a gold-plated bronze sheet into a fortune cookie, a technique Noguchi likened to origami—which he would return to whenever he worked with metal—and his way of transcending Brancusi's influence.

In one interview, Noguchi says he deserted abstraction in the 1930s, feeling as if he did not have enough life experience to 'luxuriate' in the genre.

He travelled, learning ink painting from master Qi Baishi in Beijing in 1930, and creating a monumental anti-fascist cement frieze, History Mexico, in 1936 for the Abelardo L. Rodríguez Market in Mexico City at the invitation of Diego Rivera. (Rivera is said to have put a gun to Noguchi's head after learning of his affair with Frida Kahlo.)

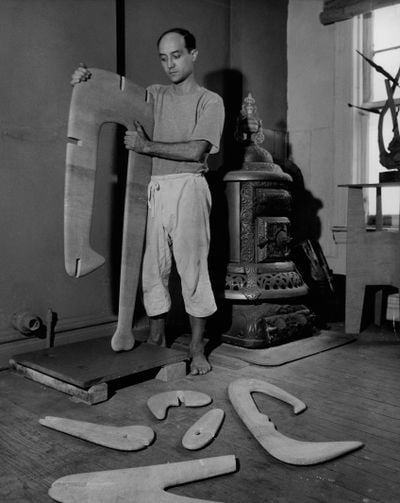

It was apparently after the war that Noguchi returned to abstraction. What emerged, besides a later proposal for a towering, black-arched memorial that freezes the horror of atomic impact (Memorial to the Dead, Hiroshima, 1952/1982), were abstract stone figures constructed like 3D puzzles, with interlocking 'bones' held together by blanks, tabs, and gravity. (Designs on grid paper meticulously map out each element in black ink.)

Among the examples in Noguchi—unfortunately clumped together to prevent sight in the round—are the monumental Avatar (1947), three biomorphic pink Georgia marble legs intertwined as if to keep one other from collapse, and Humpty Dumpty (1946), a ribbon slate deconstruction of its namesake.

Absent was the nearly ten-foot Kouros (1945), whose marble blades are precariously held by interlocking pieces at the breastbone and mid-section—an 'open, skeletal structure' that scholar Amy Lyford describes as work that 'foresees its own relocation.'2

There was definitely a profound restlessness to Noguchi's search for forms that could encompass his fluid identity, whether between Japan and America or art and design.3 Stone, which he called timeless, particularly resonated. 'I'm a person of the Stone Age era and I'm also a person of this era', he said 4 —'the whole world' is a 'place where you belong'.5

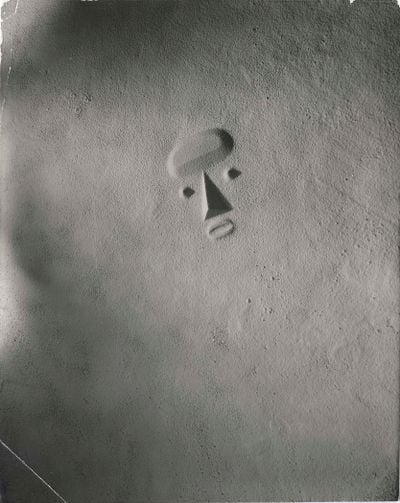

While a man of the space age, Noguchi was interested in 'going one below'.6 He communicated that earthbound perspective in the photographic proposal for a Sculpture to be Seen from Mars (1947): a face rendered in sand that looks uncannily like the sphinx some see in a 1976 Viking 1 photograph of the red planet.

Even the artist's first illuminated 'Lunar' sculptures approximated their surfaces with Arizona's landscape, where he spent 1942 interned. My Arizona (1943) is a white, mound-quartered fibreglass wall piece with a hot-pink Plexiglas square casting hot shade, while a three-fingered Magnesite hand grasps three red shards lit from within by electric light in Red Lunar Fist (1944).

This was an idealist with his feet on the ground—what he called 'a modern medium'. Someone who wanted to commune with 'the natural forces inherent' in earthly materials. 'If we worked with stone, we wanted to find that stone,' he said in 1973.7

Among the artist's basalt pillars, Age (1981) tracks an intimate discussion. From a base carved into a perfect cube rises a rough column whose shape suggests a torso, with puckered marks lightly gradating a smooth black sternum and rib-like grooves that appear like fingers swiping clay.

His desire to 'view nature through nature's eyes' gave Noguchi's sculptures a profound sense of post-human empathy. Take This Tortured Earth (1942–1943), a proposal for a monument created amid World War II. Cast into bronze in 1977, an earth-like surface marked by cuts and openings has been 'sculpted', quoting curator Kate Weiner, 'with bombs'.8

Earth was Noguchi's constant companion—photographs from 1949 to 1983 track journeys from Cambodia to Peru—as he patiently explored what its materials revealed. When tapping stone, he described receiving 'the echo of that which we are—in the solar plexus—the centre of gravity of matter', giving 'the whole universe ... a resonance'.9

'One of the most important things about Noguchi is that he took a narrow, provincial concept of formalism and reframed it as materiality,' says curator Katy Siegel.10 'Instead of fixating on a tiny point in the history of modernism, he engages with a big history'.

That big history, encapsulated in a room in Noguchi titled 'Landscape of the Mind', is grounded in a deep and expansive materiality. Double Red Mountain (1969) is a large Persian travertine table on Japanese pine from which twin buttes emerge, their bases pockmarked from Noguchi's chisel; while Time Lock (1944–1945), an upright slab of Languedoc marble, undulates with smooth mounds.

There was definitely a profound restlessness to Noguchi's search for forms that could encompass his fluid identity, whether between Japan and America or art and design.

Hanging between them like a warm sun is a giant, spherical Akari 120A (c.1957/c.1963), made from Washi paper and bamboo reeds: a version of the now-ubiquitous paper lamp Noguchi conceived in 1951 after the Gifu mayor in Japan asked him to modernise the region's traditional fisherman's lantern.

Noguchi recalls Christo deciding that, while Christo 'packages objects' Noguchi is 'packaging light'.11 A sea of these lightforms populate Noguchi in various shapes, sizes, and configurations; among them, totems whose structural geometries hark back to Brancusi.12

That these lamps are so common—granted, not every paper lamp is an Akari, those are still fabricated in Gifu—speaks to Noguchi's motivation that everyone could have art in their homes.13 He believed that 'Sculpture can be a vital force in our everyday life if projected into communal usefulness.'14

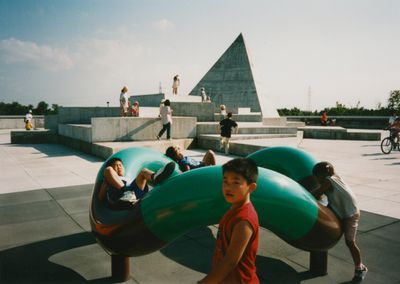

Communal usefulness extends to play and pleasure in Slide Mantra (1985), an elegant botticino marble slide installed outside Noguchi's solo presentation at the U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1986, the first time the pavilion was ever dedicated to a single artist.15

There's a picture of Noguchi testing the work, just two years before his death at 84: the embodiment of a seriously playful spirit who approached sculpture as a conduit for spatial activations, which explains why gardens and parks were an enduring interest.

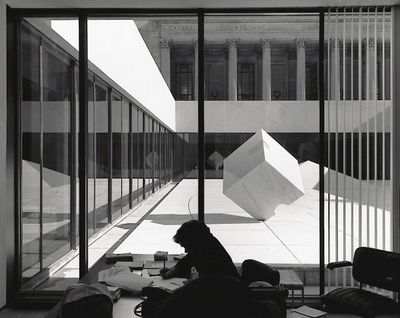

Models, designs, and documentation in Noguchi feature, among others sites, sunken gardens in New York City at Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library (1961–1964) and Chase Manhattan Bank Plaza (1961–1964), the latter functioning as a fountain in the summer; and the UNESCO gardens in Paris (1956–1958).

Study models for play equipment (1966–1976) show miniatures for functional sculptures, some fabricated for the 400-acre Moerenuma Park in Sapporo. Opened in 2005 after construction commenced in 1982, this is the culmination, quoting Alexandra Lange, of Noguchi's 'desire to shape space'.16

Five versions of the modular 'Octetra' series, each unit a pyramid composed of five hollowed-out tetrahedrons (and fabricated for Moerenuma in red concrete), are included in A New Nature at White Cube, which builds on the foundations that Noguchi laid with its display of models like Play Mountain (1933).

Apparently, when Noguchi presented this bronze proposal to turn a New York City block into a man-made playhill to Parks Commissioner Robert Moses in 1934, he only gained Moses' 'perpetual antagonism'.17

Central to A New Nature is the restaging of Ceiling and Waterfall (1956–1957), for which the artist used steel ranks and aluminium slats to create the effect of a cloudy sky and a fountain wall in the lobby of 666 Fifth Avenue in New York. The installation's permanent removal in 2020 followed years of concerted effort by the Noguchi Museum, set up by the artist in 1985, to preserve the work in situ.

While an amazing opportunity to experience Noguchi's translation of sculpture as 'a preoccupation with those palpable voids and pressures, the punctuations of space,'18 this architectural display also contextualises Noguchi's steel works, a material rooted in the city that staged many of his ideas.

It was in NYC, after all, that Noguchi unveiled News in 1940, a 22-foot-tall cast stainless steel bas-relief sculpture of seven socialist-futurist journalists forming a lightning bolt above the main entrance of 50 Rockefeller Plaza—at the time the largest metal bas-relief sculpture in the world.

Noguchi expressed an uneasy relationship with New York at times, as he did with metals of various kinds. It made no sense to work with granite in a city, he said, preferring to work with the stone in his studio in rural Japan.

But he found his way. 'In the city, you have to have a new nature', he said. 'Maybe you have to create that nature.'19 Folding metal sheets into rock with sculptures like Neo-Lithic (1982–1983), a hot-dipped galvanised steel obelisk, was that creation.

Among his final works, Noguchi's steel sculptures seem to resolve a remarkable life's tension, which he expressed to Buckminster Fuller in Spoleto, his arm looping into a red Octetra's void. 'I'm always being torn from opposite ends, or . . . in revolt against one and finding support in the opposite.20

Amid his metallic lifeforms, one particular quote speaks to the formal unity that Noguchi constantly sought in a complex, fragmented world. 'Where opposites finally come together, I see a surprising purity', he said. 'Stone is the depth, metal is the mirror. They do not conflict.'21 —[O]

1 Amei Wallach, 'Hanging Out With Bucky, Thinking Big', The New York Times, 21 May 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/21/arts/design/21wall.html

2 Amy Lyford, 'Noguchi, Sculptural Abstraction, and the Politics of Japanese American Internment', Art Bulletin, 85, no. 1 (March 2003): p. 149.

3 Michael Blackwood, Isamu Noguchi (1972). Documentary.

4 Paul Cummings, 'Oral history interview with Isamu Noguchi', 7 November–26 December 1973, Original typescript. Washington D.C.: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

5 San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 'Isamu Noguchi: There's no such thing as time', YouTube, 1 April 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Y05dzPTnq8

6 Cumming, 1973.

7 Cummings, 1973.

8 Kate Wiener, 'Introducing: Isamu Noguchi', The Barbican, 2021, https://sites.barbican.org.uk/introducingnoguchi/

9 Wall text from Noguchi, Barbican Centre, London (30 September 2021–9 January 2022).

10 Karen L. Ishizuka, Katy Siegel, Danh Vo, and Devika Singh, 'Transnationalism and the Work of Noguchi', Exhibition Catalogue, Noguchi (Prestel: 2021), p. 258.

11 Paul Cummings, 'Oral history interview with Isamu Noguchi', 7 November–26 December 1973, Original typescript. Washington D.C.: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

12 Ibid.

13 Barbican Center, 'Noguchi: In His Own Words', Belle Vue Productions, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IbcleKnGEMU

14 As quoted in Dakin Hart, 'What Did Noguchi Mean by "Space"?', Exhibition Catalogue, Noguchi (Prestel: 2021), p. 133.

[15] Glenn Adamson, 'Representing America: Isamu Noguchi at the 1986 Venice Biennale', Noguchi, https://www.noguchi.org/isamu-noguchi/digital-features/representing-america-isamu-noguchi-at-the-1986-venice-biennale/

[16] Alexandra Lange, 'A Journey to Isamu Noguchi's last work', Curbed, 1 December 2016, https://archive.curbed.com/2016/12/1/13778884/noguchi-playground-moerenuma-japan

[17] Isamu Noguchi, Play Mountain (1933, cast 1977), Noguchi Museum Collection, https://www.noguchi.org/artworks/collection/view/play-mountain/

[18] As quoted in Dakin Hart, 'What Did Noguchi Mean by "Space"?', Exhibition Catalogue, Noguchi (Prestel: 2021), p. 133.

[19] Wall text from Noguchi, Barbican Centre, London (30 September 2021–9 January 2022).

[20] Michael Blackwood, Isamu Noguchi (1972). Documentary.

[21] Noguchi Museum, Walking Guide, Area 14.