Frank Walter's Expanding Universe

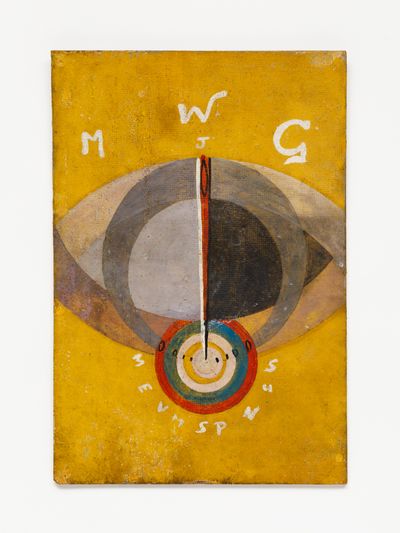

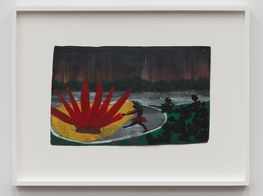

Frank Walter, Tambourine and Harp (n. d.). Courtesy MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main. Photo: Axel Schneider.

At the 57th Venice Biennale in 2017, Antigua and Barbuda's inaugural pavilion stood out among the rest. Staged in a side gallery of a former 15th-century monastery located far from the Giardini and Arsenale, Barbara Paca, cultural envoy to Antigua and Barbuda's Ministry of Culture, invoked the enduring spirit of Frank Walter.

Paintings and sculptures were carefully arranged among objects from Walter's island home and studio, including his Olympia typewriter and an 8000-page autobiography stacked into a statuesque column topped by a handmade wooden toy—a fraction of the roughly 50,000-page archive that Walter produced until his death in 2009, along with around 470 hours of voice recordings that blend musings on his life with reflections on art, history, and belonging.1

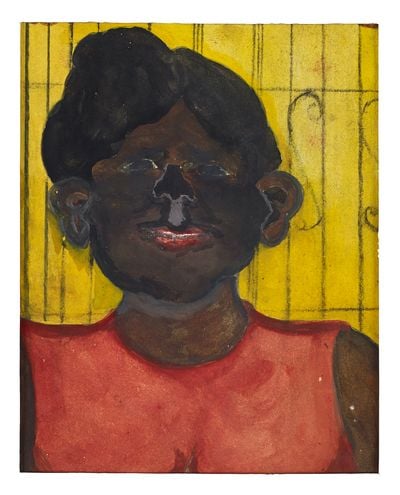

In total, Walter left behind over 5,000 paintings, most undated and rendered on card, Masonite, and the backs of polaroid boxes from his time running a roadside photo studio between 1968 to 1976.2 Ranging from striking geometric abstractions and verdant landscapes flush with cascading coconut fronds and banana leaves, images were arranged according to genres that Walter dictated: landscape, portraiture, galactic, sign, writing, heraldic, abstract, and scientific.

Among them, Psycho Geometrics appears on the cover of the extensive catalogue produced for the show. A two-dimensional faceted orbed star with blocks marked by a medley of orange, red, yellow, white, navy, and a single sky blue triangle, is flanked by four smaller versions at each corner of the frame, a black background completing a colour run echoing Antigua and Barbuda's flag.

Titled The Last Universal Man, this was a dizzying yet concise display. The Studio Museum's Thelma Golden called it 'a fascinating and moving glimpse into the life of the prolific and profound multidisciplinary artist'. In Artforum's December 2017 issue, curator (and recently appointed Chisenhale Gallery director) Zoé Whitley wrote: 'Alternating between a clear-eyed vision and an undeniable impulse for myth-making, Walter embodies the lived postcolonial experience.'

Aside from being a multidisciplinary artist, Walter was also an astonishing polymath, as demonstrated by vitrines filled with photographs, clippings, musical scores, poems, and notes, plus an invite to the first meeting of the Antigua and Barbuda National Democratic Party, which Walter founded in 1968.3 (In 1971, he ran for prime minister on a platform for sustainability, losing out to his cousin George Herbert Walter.) Framing a trio of stunning abstract paintings on one wall were charts tracing Walter's family tree: a heritage bound to slaves and plantation owners that grew into a fantastical mapping of illustrious European heritage that included the likes of England's Charles II.

Somewhere between truth and fiction, Walter's ancestry was a lifelong preoccupation, which relates to the colonial legacies of his island region and how they impacted him. In the powerful voice recording 'How I Became European', among many on the artist's website, he notes: 'I was constrained to be bothered as to whether I belonged to that family or not'.4 This constraint fuses his life and work. 'Art is a festival in which a narrative is told', he wrote—'it makes its drama constantly; and speaks / In human flesh.'

As Hall and Fanon developed groundbreaking theories that shed light on the psychological, cultural, and sociopolitical impacts of racism and colonialism, so Walter produced his own cosmologies, insights, and creative worlds to refuse the reduction of his being.

Born in 1926, his mother died in 1937 and his father walked out shortly after, leaving him and his four siblings to live with their paternal grandmother. In 1939, Walter enrolled at the illustrious Antigua Grammar School as part of an initiative for integration, where he was encouraged to pursue law but opted for agriculture instead. Upon graduating in 1944, he trained at Friar's Hill plantation before joining the Antiguan Sugar Syndicate in 1948, becoming one of the first in Antigua to break the race barrier when he ascended to management at the age of 22.5

Walter intended to use his role to radically overhaul the toxic culture inscribed into the farming system by colonialism—a way to recuperate a tradition of working the land, which he celebrated. 'My labourers were no longer made to feel inferior', he wrote of the time; 'I am purchasing your labour, not your entire being', he told them.6 As Paca notes, sugar production records were surpassed under Walter's watch, but when he was invited to manage the entire Sugar Syndicate he declined. Ambitions of modernising Antigua's agricultural industry led to Europe in 1953, where dreams abruptly met racist realities.7

The artist's current retrospective at Frankfurt's Museum für Moderne Kunst (16 May–15 November 2020) attempts to parse this experience by placing a selection of Walter's work—including a series of his enigmatic portraits—in dialogue with 12 artists. Kapwani Kiwanga's commissioned installation Matières premières (2020), for instance, hangs reams of white paper made from sugarcane fibre from the ceiling; while Howardena Pindell's 1980 video Free, White and 21 sees Pindell's recollections of racism interjected by shots of the artist in whiteface dismissing them.

In particular, John Akomfrah's portrait of cultural theorist Stuart Hall's life and work, The Unfinished Conversation (2012), and Isaac Julien's 2008 documentary on Frantz Fanon both touch on the rude awakening that occurred for so many upon arriving in Europe and becoming swiftly othered by its gaze. An empathetic frame to understand the exacerbation of Walter's schizophrenia abroad, which he described as 'another dimension, into which the conscious mind ... is transmitted,' often as a 'necessity to fight one's way out of brutal assault.'8

As Hall and Fanon developed groundbreaking theories that shed light on the psychological, cultural, and sociopolitical impacts of racism and colonialism, so Walter produced his own cosmologies, insights, and creative worlds to refuse the reduction of his being. In Sons of Vernon Hill, the only book he published in 1987, he wrote: 'we see the black man not divine, while the white man is, and vice versa, due to complexes left untamed to become pathological issues.'9

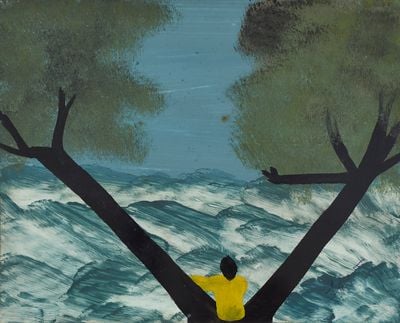

In 1954, shortly after arriving in London, Walter was invited to read two poems dedicated to his plantation work on Caribbean Voices, a BBC overseas service broadcast. The show's director likened his writing to the German Romantics—an alignment Walter agreed with, and which he demonstrated in the recurring Rückenfigur that appeared in his painting. In different settings, a single black figure stares out towards the sea, echoing Caspar David Friedrich's Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818)—an expression, perhaps, of the horizon that Walter constantly held in his sights.

Walter felt more welcome in Germany; an affinity he connected with his familial roots, which at times resulted in complicated leanings. (Among his portraits is an ash-faced Hitler, who appears again playing cricket with Antiguan men, and later as a man of colour woven into a rainbow flag.) Finding only menial jobs in Europe, he worked in Ruhr district mines between 1957 and 1959, where he wrote a symphony inspired by a morning walk from Bonn to Dusseldorf. In January 1960, he moved to Stoke-on-Trent, developing paintings exploring molecular science while taking night classes in chemistry, metallurgy, and physics, and working at Wedgwood and Minton tile factories to make ends meet.

One May morning that year, Walter awoke from a dream of Charles II urging him to Scotland, and immediately travelled north. Before organising the first exhibition of Walter's works in England with Harewood House Trust in 2017, Ingleby Gallery in Edinburgh staged a major solo show in 2015 around Walter's Scottish sojourn. Some 50 landscapes representing both Antigua and the British Isles, many painted from memory, were presented alongside the wooden hut that Walter built between 1994 and 1996, and where he lived for the rest of his life.

By the time Walter returned to Antigua in 1961, tourism was fast replacing agriculture, and he moved to Dominica to cultivate family land. Keen to rejuvenate the farming industry, he received 25 acres from the Crown Lands Department, 10 located in the rainforest, which he cleared and tended, developing a kiln system to turn wood from the trees he felled into charcoal in the process. He would call this period one of the greatest poetic events of his life. Commemorated by the mahogany and acacia figures that he started to carve there, from ancient Arawaks to animals of all kinds: a stunning collection of around 600 pieces that prominently display his skill as a sculptor.

In 1965, Walter took a trip to England to calm his hallucinations, spurred by suspicions that his land would be confiscated, but was barred from disembarking the ship for the lack of a visa. Confined to his cabin, he saw visions of sea gods and monsters through the porthole. 'In later writings,' Paca notes, 'he recalls the ship's oculus becoming a portal into another world known only to him'.10 This threshold was translated to round oil paintings executed on spools cut from linoleum and asphalt roofing tile, their subjects ranging from the Hell's Gate Street Band and Austrian choir boys, to the recurring form of a boat's white sails.

He was at once a product of his time and light years ahead of it; an artist who left universes to explore in his wake.

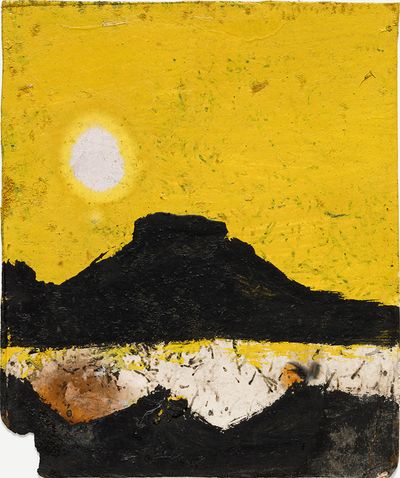

In the end, Walter's fears were correct. The Crown took his lands, and after a futile legal battle he returned to Antigua, but not before sailing aimlessly (and forlornly) at sea and nearly drowning off Martinique.11 A series of self-portraits on a boat seem to capture the intensity of the time. Painted on the back of polaroid film cartridges, a deep purple sea is inflected with hints of flaming orange, as white swathes push up against Walter's vessel. In the distance, land rises up like an ominous shadow into a darkening sky—silhouettes that reappear in the Frankfurt show, as in a landscape that meets a psychedelic yellow sky with a white-hot sun.

Moving into his former childhood home on Antigua towards the end of the 1960s, Walter worked out of a studio he helped build with his uncles as a young woodworking apprentice. He made wooden toys to sell while running a photography studio (he joined the Press Photo Services, run by Reuters' photographer Gerald Price, in 1973), whose archive is opened up beautifully by academic Krista Thompson in an essay for the MMK exhibition catalogue. Exploring Walter's gaze in relation to the community he photographed and the multiple perspectives his images hold, Thompson cites 'sociologist Avery Gordon's description of the "in between space" created by dreamers and architects of future utopias'.12

It was around this period that Walter ran for prime minister, advocating against the tourist trade in favour of water conservation, investment in agriculture, and the preservation of oral histories. 'We would rather be in a position to reap what we sowed than to have raiders come to steal, or to have to steal ourselves', he wrote in the essay 'Better Late Than Never'.13 He also planned out future exhibitions, seeking venues with the Royal Ordinance, Grimaldi Shipping Lines, a German youth hostel, and the National Coal Board.

Walter's final stop was Bailey's Hill, where he lived out his twilight years. Later works include six oil paintings on wooden panels composing the 'Milky Way Galaxy Series': celestial dramas characterised by golden yellows that recall luminous details in church frescoes. Left Side of the Milky Way Galaxy, for example, looks like the tail of a brilliant comet as it charges forward on a curved, downward trajectory, as grey bands cut the path to mark planetary orbits, while an elegant yellow boomerang returns to the radiating sun in Right Side of the Milky Way Galaxy. He also wrote poems about the planet Jupiter and travelling to the moon, and recorded a one-man opera as a philosopher prince.

It is in these cosmic works, which recall Sun Ra's conception of space as a site of liberation, that Walter's approach to life becomes most evident; as a journey in search of worlds capable of accommodating the depth and breadth of far-reaching hopes and visions. He was at once a product of his time and light years ahead of it; an artist who left universes to explore in his wake.—[O]

—

1 See: http://www.frankwalter.org/

2 Frank Walter: A Retrospective, MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main, exhibition catalogue, edited by Barbara Kasten and Susanne Pfeffer (Koenig Books, 2020), p. 372.

3 Frank Walter: A Retrospective, MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main (16 May-15 November 2020), exhibition booklet.

4 See: http://www.frankwalter.org/videos

5 Frank Walter: The Last Universal Man 1926-2009, exhibition catalogue for the pavilion of Antigua and Barbuda at the 57th Venice Biennale, edited by Barbara Paca (Radius Books/La Biennale di Venezia, 2017), p. 257.

6 Ibid., p. 253.

7 Ibid., p. 257.

8 Frank Walter: A Retrospective, p. 392.

9 Frank Walter: The Last Universal Man 1926-2009, p. 306.

10 Frank Walter: A Retrospective, p.398.

11 Frank Walter: The Last Universal Man 1926-2009, p.296.

12 Krista Thompson, 'History on the Underside: Refiguring the Rückenfigur in Frank Walter's Painted Landscapes and Photographs' in Frank Walter: A Retrospective, MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main, exhibition catalogue, edited by Barbara Paca and Susanne Pfeffer (Koenig Books, 2020), p. 375.

13 Ibid., p.301.