John Akomfrah

John Akomfrah at his London studio, 2016. © Smoking Dogs Films. Photo: Jack Hems. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

John Akomfrah at his London studio, 2016. © Smoking Dogs Films. Photo: Jack Hems. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

The polyphonic has been a guiding principle in John Akomfrah's work. As a founding member of the Black Audio Film Collective, which was active from 1982 to 1998, Akomfrah produced experimental documentaries and films that responded to growing social turmoil in 1980s Britain.

The collective's first film essay, Handsworth Songs (1986), licensed and screened by the broadcaster Channel Four Television, was a response to the riots in London and Handsworth, Birmingham, in 1985; newsreel footage, archival photographs, and interviews were used to construct a multi-layered film that destabilised the mainstream 'regime of representation,' which racially profiled black communities in a discriminatory social environment within the conservative politics of the United Kingdom under Thatcher.

Exploring ideas of culture, ideology, representation, identity, and politics through a collective working process provided Akomfrah with the language to expand upon these considerations, later creating Smoking Dogs Films in 1998 with Lina Gopaul and David Lawson, his former collective partners. Today, Akomfrah's installations consist of multi-channel moving image works that transcend traditional forms of broadcast, producing film compositions with sound and text that are informed by thinkers like cultural theorist Stuart Hall.

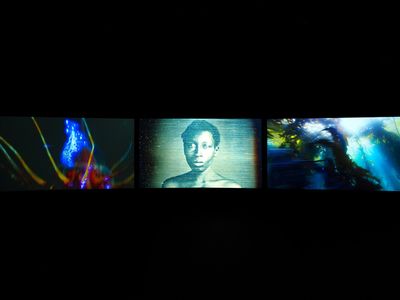

His films are atmospheric and reflective, exhuming personal and collective memory, bringing in juxtapositions and dialogues between disparate moments and narratives throughout history. The Unfinished Conversation (2012) is a three-channel film installation reflecting on Stuart Hall's life—a mix of documentary footage and the artist's narrations. The multi-screen Vertigo Sea, which premiered at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015, considers histories of slavery, migration, and environmental crisis.

This conversation with Akomfrah was held on the occasion of his solo exhibition at the New Museum, Signs of Empire (20 June–2 September 2018). The show presented early directorial work with the Black Audio Film Collective alongside more recent productions, like Transfigured Night (2013/2018): a two-channel video installation that explores the relationship between the postcolonial subject and the state, through an 1896 German poem by Richard Dehmel and an 1899 musical composition by Arnold Schoenberg.

FKCould you talk about your experience as part of the Black Audio Film Collective. and how a dislocation of individual authorship allows for a sharing of risk taking?

JAThe exhibition at the New Museum included one of the first pieces that I worked on inside the Collective: the tape slide work that we did over two years called 'Expeditions'. I was very happy when Massimiliano Gioni said that he wanted to include it because an unfinished conversation was set in motion regarding the desire to name ourselves in the collective title. It's unfinished because one of the many compulsions taken up in collectives, and for being part of one, remains this question of naming, and of finding a space either within a society, state, or town—call it what you will—of autonomy in which one can become.

We were a number of individuals with different parents from different parts of the African and Asian world, but we wanted to be black artists. The preconditions of being black artists was to choose a state in which we could name ourselves in that form, and without the Collective I'm afraid that would've been impossible. I also acquired modes of thinking that are ongoing, unfinished. It involves conversations that I have with myself about the question of form, the nature of identity—political or otherwise—and the relevance of the work. Clearly this is not 1982, and if I were to start again and be part of a collective or choose to be part of a collective, we would probably operate in a slightly different way to how Black Audio was constituted.

FKCan we talk about the legacy of Stuart Hall and what you have described as a 'double inscription' in The Unfinished Conversation?

JAOn the one hand, the work was an attempt at a collaboration between Stuart and myself. The conceit was to open a space for a dialogue with him about the post-war period and the migrations of identity—racial and otherwise—in that period. Now, as that conversation proceeded, it became clear that in a way he was an emblematic example, and that situating his formation—political, psychic, and cultural—at the centre of The Unfinished Conversation was one way the conversation between us could proceed with a degree of effectiveness.

Having decided that he would be the centre of the work, it was clear that it couldn't just be a biographical account of the post-war period. We couldn't use him, his life, as the entire story of the emergence of the Left. Other strategies needed to be found, which had some proximity to his life, but weren't exactly the same. I didn't want to reduce the entire backdrop of the historical or the political to the biography of one figure. I knew that we were going to have to do the two things at the same time, and that's what I initially meant by the double inscription. On the one hand, one would say something about the character, its formation, its impact, and its influence. But one would also then want to say something about the backdrop to that character.

I can't think of any other way in which we could've done it. We managed to do something that was slightly more 'biographical' in a single-screen version that I made for the cinema called The Stuart Hall Project (2013).

It seemed to me when we started The Unfinished Conversation, that if you opt for the triptych form you were then necessarily involved with questions of discursivity, mixed economies, the dialogic, and the constant conversation between a number of elements simultaneously. I knew from the beginning that the minute I decided it would be multi-screen, that we were going to have to fill those screens with discordant elements; things that didn't necessarily sit in harmony with each other. The trick, the whole point of the work, was to find the harmony, if you will.

FKHow does The Unfinished Conversation connect with your experience in the Black Audio Film Collective, which saw you working together to address the regime of representation?

JAI think one of the things that was important for me was the question of the polyphonic. Stuart Hall was a quintessentially polyphonic figure who was very comfortable with situating his argument at a variety of crossroads. One only does that with any confidence if one believes, profoundly, in the polyphonic. In other words, the ability to marshal an array of voices or at different registers, shall we say, in the service of a broader ideal, which is not reducible to its components.

The whole point of polyphony is that you have a kind of call and response, yin and yang—call it what you will. That was very much one of the organising principles by which all collectives strive to work, and Black Audio was no exception. If you have more than three people together and they all decide that they will name their practice in the same way, then you are necessarily inviting the polyphonic into your life. The striking overlap between collective practice, which is premised on the polyphonic, and a political project initiated by a figure, meant that there were some overlapping affinities that could be explored.

The first time I met Stuart, we invited him to come to our workshop because we were making the film Handsworth Songs about an area in England, Birmingham, where he had lived and taught from 1964 until the late seventies. The fact that we were invested in making a film about an area that he had worked in necessarily provided us with the basis for a conversation. One of the reasons we had gone to Birmingham to make the film at all was in part to do with the fact that he had been there in the first place. So, you have these complicated overlaps that were the basis of the dialogue with him.

When I met Hall in person, there was this very same sense of déjà vu. It's slightly arrogant to say that we recognised him when we first met him, but it's true. He felt very familiar because we had already, for years, been reading his work. I think there is something about the tensions, the ambiguities, and the turmoil in his life that perfectly mirrored our own. Here was a figure that was deemed the monument of the hybrid. He had come from Jamaica to attend college in England. He worried about the tension between the two worlds and navigating the spaces between the two as a figure who had arrived in England not necessarily being black, white, or English.

In other words, there were recognisable tensions for us. It was interesting to observe—both from afar and close-up—a figure whose life, thoughts, and activities had in some way been rehearsals for our own. Migrating ideas, concepts, and ways of seeing and being from his work onto a collective project wasn't that difficult.

FKYou often speak about dualities, dialectics, indexes, juxtapositions, and reflections when discussing image-making approaches and strategies. Could you talk about how you work with images in order to produce a dual situation of being present in the moment while allowing the viewer to imagine 'elsewhere'?

JAEvery situation, every exhibition, sort of forces you to think about this in a slightly different way. We are dealing with practices of indexicality—temporal machineries that generate desire and thought and so on. It seems to me that part of what one needs to do with all image- and lens-based projects that have a kind of glow of an afterlife—let's call it the archival trace—is provide that material with its own legitimacy, with its own specificity, so that one can then tease it to have a dialogue with the present. It's only in the process of allowing the possibility for these migrations that other narratives emerge.

When things insist on the specificity of their moment and their desire to simply stay in those moments, one doesn't get that migration. Without that migration there is no possibility of further development. I am, in all humility, a servant of these things, whether they are stories or photographs. I am a servant in a sense that I am here to basically recognise your ontological status and to confer on that status a certain amount of legitimacy. Once I've done that, or once we've agreed that this has happened, it seems to me that the other question we need to pose to those moments, things, or objects is: 'Would you not like to come for a walk? Why don't we just go somewhere new, just for a moment?' It's a provisional request, not a permanent one. You are not going to be transformed into something other than what you are. But it seems to me that if you are able to step into this new space and respect it, something interesting will happen.

I have found that, over the years, most frames are sufficiently inquisitive and generous to make viewers want to take that walk. Usually when they don't, it's because it's not an appropriate moment. There are films that I saw 25 years ago in archival collections that I try to engage in other projects, but they simply refuse to budge, because the projects themselves, the demand, wasn't right for them. So I start from this profoundly libertarian space, which says that all things are possible with images. But the moment and the conjunctions when they can circulate are circumscribed. There is freedom but there are also constraints, and one needs to recognise when the two are absolutely aligned to make something possible.

FKHow does the form of the film essay relate to a strategy that often deals with irreconcilable contested histories? For example, your use of double screen, voiceover, text, and blending historical footage with your own in Transfigured Night.

JAI'm always placed in that camp, and I don't have a problem with that. I've learned more from film essays than just about any other cinematic form. The space in which I started with the Collective, one that I thought I occupied, has to do with being fundamentally agnostic about the claims of either 'documentary footage' or 'fiction footage'. What we found in all our studies of early cinema is that there are ways in which the original document circulated in the time machine of the cinema. The early cinema from the late 1880s to the 1920s seemed to not really make a distinction between fiction and documentary; they were always the same. And so, because of that, this notion that somehow there are absolute demarcations between the two made no sense.

The film essay, for me, must start with the assumption that just about everything is open to a question or a reflection. That covers the status of what you're watching, where it belongs, who is behind and in front of the camera, and who is writing the voices; all of this stuff is up for grabs, and it's only up for grabs if you say to yourself in advance, 'I will not accept the categories that you're throwing at me as permanent ones. 'This is a fiction film', 'This is a good documentary', or 'This is a bad one'—all of those facile demarcations have to be under scrutiny, under question, or have to be approached from a place of profound agnosticism before anything happens, really.

I think I was blessed to be part of a collective that started off making slide-tapes and looking at the histories of colonial fantasy for us to realise that there were these continuities that connected narratives across lines that were supposed to be clearly drawn—from novels to essays, films, travel writings, diaries, and letters. There were overlaps, and there were discontinuities, too. Clearly there were differences between a letter written privately to a husband and a travel journal, which was published. But there were also incredible continuities and overlaps between them, and that's one of the things we set out to do. Works like The Unfinished Conversation and Transfigured Night are happy to cull elements from the newsreel—pulling from the history of German serial music, or the writings of Fanon and Nietzsche—to somehow forge a language about the coming of the post-colony from these disparate elements. Most of that is trying to search for spaces of legitimacy, for itinerant ways of doing things.

FKCould you talk about the untranslated and uncaptioned voices that speak on the soundtrack in the film?

JAI love dirges as a song form. I love their mournful quality, because of the insinuation of elegy that they bring to things. Take that Frantz Fanon phrase at the beginning of Transfigured Night: 'What can we say when we can't speak anymore, when we have to speak but don't know what more we can say?'

What can we say when the condition of wordlessness, as Nietzsche would put it, is absolutely the preferred option? As I said, I try to persuade things to move into other spaces in which they can acquire a new garment of identity.

People approached these ethnographic recordings done by field recorders, which are now stored in the British Museum, from the angle of the folkloric or the ethnographic. It seemed interesting to me to persuade them to speak to the theme of a project. I took the whole Transfigured Night premise from Arnold Schoenberg, and it's such a wonderful idea, because in the short story a man takes a walk on a moonlit night with his loved one, and the woman says: 'Listen, I'm carrying a child, I do love you, but I'm carrying a child, and the child is not yours.' In other words, 'I come to this union in a state of "imperfection," because I've been inseminated by someone else.' And he replies: 'You have to find the courage'—as most colonial subjects must do when they first encounter the postcolonial state. They have to say to the postcolonial state: 'Yes, we love the thought and the idea of it so much that we are happy to be in this union with you. Even though we know of these imperfections, we are happy to be in this union because we believe we will make something new; the child will be ours, we will look after it as our own, and this new country will be great.'

It seems to me that these are the claims of fidelity that the postcolonial subject made to the postcolonial state. The postcolonial state generally said, in this slight hybrid form, 'If you believe me, we can adapt.' Certainly, my parents did, as did the parents of most people I know. We all turned up on the day of independence, waved our flags, clapped, and said: 'Yes, we'll come along with you on this project.' But on that night of transfiguration, the pact and the union failed. What can you say about these things now except for lamentation and elegy? What do you say except to lament the passing of the moment?

FKCould you discuss the disparate narratives in Vertigo Sea, which you tie together to reveal this continuing importance of the sea in today's migration crisis, amongst other things?

JAIn part, this started because I wanted to register a change in the utopian project of migration. When you look at the young 22-year-old Nigerian man whose voice opens Vertigo Sea—talking about being trapped at sea and hanging on to a tuna net—the idea that propelled his desire to move away is pretty much the same as my mother's, in the sense that these are two individuals separated by five or six decades, each of whom believed that other lands held the promise of decadence. However, the conditions that underscored the journeys are two very different ones. My mother arrived in the relative comfort of a ship to Britain and this man was stuck in a pirogue that stood very little chance of making it across the Mediterranean.

These registers of danger suggested the need to return to questions of the sea with multiple lenses to see how many forms of subjectivity could be located in it. I was trying to locate a series of episodes in which particular subjectivities could be isolated.

I also think there's a way in which we have to be very modernist, in the sense that we need to know what is not possible anymore. Or rather, we need to teach ourselves to speak in a very different way about questions of subjectivity, because holding on to the notion that there is absolute demarcation between the lives and misfortunes of the humpbacked whale and the enslaved African in the 16th century is a mistake. There are overlaps and striking affinities between those lives that can only be recognised if you get rid of this idealist assumption that there is a hierarchy of subjectivity, at the apex of which sits the human.

This was a very important experiment for me—trying to do a project in which different states of subjectivity across species demarcations could be brought in to reach a kind of affective proximity.

FKHow do you deal with images that display human suffering, while understanding the limits of representation and the ethics of dealing with histories that have greatly affected lives and communities around the world? You handle your narratives and characters very delicately, this is certain.

JAThere's a part in The Unfinished Conversation where the conundrum of what I do is writ large. It's in Vietnam in 1966, a woman has stepped on a landmine and she's had her legs blown off. They've been amputated, and she's been taken back to the hospital, where the amputation had taken place, so they can check to see if she's okay. When she arrives, there is a BBC TV crew there and they see her being carried into the hospital. They follow her in a kind of handheld shot into the ward where they proceed to film her. No one has asked her for permission, she is absolutely embarrassed, because she is clearly at her most vulnerable, and they proceed to film her.

Now, as you look at this young woman—she must be at most 19—you find that she begins to discover agency. At some point you see her make the choice to not disavow the filming, but to engage and use it in order to say something about herself. It is one of the reasons I am really interested in moments of un-becoming. It seems to me that there's a kind of romantic fantasy that we attach to becoming. People say the only kind of image worth looking at is when people are on top, happy, winning, struggling, marching on to the future and so on, because the assumption is that those are the only times when human or non-human agency can be seen at work. I don't agree with that.

When you have 20 tonnes of whale lying there dead being hacked to bits, the fact that the people who are hacking it to bits are so small and are able to do what they're doing in that moment of death is both a statement by the humpbacked whale as well as the people who are doing it. The fact that something is inanimate does not mean it is not speaking or saying something. The fact that someone is dead does not mean they are not saying something. And the fact that we are witnessing moments of their un-becoming is as powerful and as revealing as the moments of their becoming, if I can put it that way.

I understand that there are moments when these things are uneasy for people, and I understand that there are ethical questions at stake. One has to be mindful of the question of the photographic, but I don't think those questions should circumscribe and prescribe the status we go into, especially when what we are looking for are signs of life. I think signs of life can be found even in moments of death. —[O]