In London, Pope.L Leaves a Lasting Message

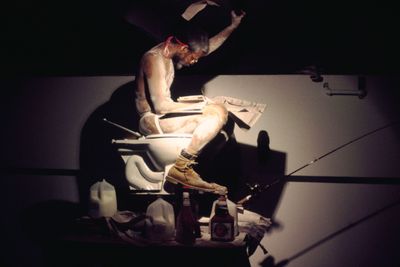

Pope.L, Eating The Wall Street Journal (Mother Version) (2000–2023). Painted wood, metal, toilets, fishing poles, plaster, calcium carbonate, plastic sheeting, Wall Street Journal and Financial Times newspapers, and light. Exhibition view: Hospital, South London Gallery, London (21 November 2023–11 February 2024). Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andy Stagg.

An installation taking over South London Gallery's main exhibition space by Pope.L, known for confronting the racial and social inequalities shaping American society, emphasises a profound absence.

White wooden scaffolding mimicking a collapsing tower is crowned at its 18-foot peak by a toilet that appears to have ejected its sitter. There are newspapers everywhere; mostly editions of the title that prompted the creation of the work in the first place.

Conceived after seeing an ad for The Wall Street Journal insinuating fortune for its subscribers, Eating the Wall Street Journal refers to a performance Pope.L staged at MoMA, New York, in 2000. Over five days, Pope.L wore a jockstrap, covered himself in flour, and sat atop his latrine tower, tearing the newspaper up and chewing on pieces doused with milk and ketchup.

Pope.L has since called iterations of the work part of a titular family. This 2023 version was created for the artist's solo show Hospital (21 November 2023–11 February 2024), as a performance without a body, where 'the material is performing.'

A toilet hangs off the edge of a pole on one flank; another lies on its side on the floor with newspapers stuffed in its tank; clumps of plaster-like matter cling to the scaffolding like mineral growths. Among the bottles lined up on surrounding shelves, sweating liquid down the walls, is a bowl of calcium carbonate powder. A sign reads: 'Dust, sprinkle at will.'

This invitation to become part of the performance seems encoded with an intentional backfire. The fine white dust seems to melt into the air once sprinkled, but not before coating the fingers. It's an apt metaphor for the tendency of whiteness—that is, the systemic structures of power shaped by histories of racial capitalism—to mark everything it touches.

As a Black man in America, Pope.L said he could never experience race as simply personal—a reality that differed from the experience of white people he knew. 'They don't see it as a larger political context that you have people who are empowered and people who are not,' he told The Guardian in 2021.

All of which relates to how Pope.L dealt with race and class throughout his practice. 'We are born into whiteness,' he told performance artist Martha Wilson in 1996. 'On the surface, it seems wholly to construct us, and the degree to which we may counter-construct sometimes seems very limited. But, I believe we can be very imaginative with limitations.'

The insistence on holding imaginative, speculative ground to challenge the constructs of racial supremacy—and its inevitable intersections with class divisions—defines Pope.L's work.

Take 'Skin Set Project', a text-based series started in 1997, where words on paper describe people of colour—including purple, green, and blue people, the latter referred to in one drawing as 'drops of water'. Or the artist's celebrated performances that saw him crawling, army style, on the streets of New York, starting with his first crawl in 1978, when he crossed Times Square in a pin-striped suit.

For The Great White Way, 22 miles, 9 years, 1 street (2001–2009), Pope.L crawled Broadway, the oldest north-south thoroughfare in New York City, wearing a superman suit, knee and elbow pads, and a skateboard strapped to his back. The process—starting at the Statue of Liberty and culminating in the Bronx—took nine years; each leg lasted for as long as he could manage at a time.

This invitation to become part of the performance seems encoded with an intentional backfire.

Responding to his own life, having witnessed his father, aunt, and brother experience homelessness, these crawls challenged the systemic indifference to poverty, as if it were a natural societal by-product rather than an engineered state. 'We'd gotten used to people begging, and I was wondering, how can I renew this conflict?' Pope.L told Wilson. 'I don't want to get used to seeing this. I wanted people to have this reminder.'

Each crawl refused the dismissal of homelessness as something to be ignored or demeaned. 'Just because a person is lying on the sidewalk doesn't mean they've given up their humanity,' the artist explained in 2002.1 They also embodied the power of empathy as an intentional act. As artist Shuruq Harb wrote in 2016, 'What Pope.L's work makes clear is that it is impossible to assume the role of leadership if you don't know what it means to crawl on your hands and knees.'

In 2019, Pope.L staged his largest crawl ever. The Public Art Fund commission Conquest saw 140 blindfolded volunteers traverse the 1.5 miles from Corporal John A. Seravalli Playground in New York's West Village, through the triumphal arch at Washington Square, to Union Square.

The performance formed part of Pope.L: Instigation, Aspiration, Perspiration, a trinity of solo shows in New York in 2019, including the survey member: Pope.L 1978–2001 at MoMA, and Choir at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Choir was a new commission that centred around an old drinking fountain suspended upside down from the ceiling in a spot-lit gallery, from which water poured into a 1,000-gallon tank. Microphones amplified the cascade's sounds, with recorded songs and chants woven into the broadcast. At a certain point, the water stopped and drained from the tank before the cycle repeated.

Vinyl letters on the walls spelt phrases referring to the history of segregation in Jim Crow-era America—a context that expanded into the present with Flint Water Meets the Mighty Hudson (2019). Published on the Whitney Museum's website, the video shows the artist pouring water from Flint, Michigan, into the Hudson River in New York, connecting Choir to the artist's Flint Water project (2017).

Flint Water responded to the injustice inflicted on Flint residents, when a state-appointed emergency manager, in a cost-cutting move, opted to use the contaminated Flint River—instead of treated water from Detroit—to supply the city's water. The results were disastrous for the health of the Flint community, of whom 57 percent are Black, 37 percent white, and 42 percent live below the poverty line.

In response, Pope.L bottled and sold tap water he purchased from a Flint resident (by paying for two months of their water bills) in the gallery of What Pipeline in Detroit. Proceeds went to the United Way, working to support Flint residents, and Hydrate Detroit, which advocates for affordable water in Detroit.

'The water is an object lesson and a reminder that Flint is not the only city in the U.S. with serious water issues,' Pope.L explained in 2018.2 It also highlights the role of 'environmental racism' in the crisis, a term describing the conditions where political decisions disproportionately harm low-income communities of colour, and the systemic lack of accountability for government officials responsible.

Flint Water also illuminated the perseverance of Flint residents and the solidarity of their supporters, as they successfully brought the issue to federal court despite political indifference. As Pope.L noted, 'the aesthetics in this work are in the immaterial: vulnerability, community, and a sense of connectedness.'3

The insistence on holding imaginative, speculative ground to challenge the constructs of racial supremacy—and its inevitable intersections with class divisions—defines Pope.L's work.

That sense of connectedness fuelled Pope.L, who died unexpectedly after opening his London show. 'If it wasn't for people, I wouldn't make or perform anything,' he said in an interview published by South London Gallery, where he sits beside his last iteration of Eating the Wall Street Journal.

In that video, Pope.L mentions a sick friend, who prompted reflections on how illness 'make[s] you a stranger to your own experience'. That got him thinking about '[his] own body, the bodies of people that [he] care[s] for, and the bodies that may not be there in the future.' Hence, the title of the show, Hospital, which draws on hospes, Latin for 'stranger', 'visitor', 'guest', and 'host', thus infusing his giant installation, designed to perform without a body, with a perpetual invitation for anyone who encounters his work from now on.

'I'll make an agreement with you guys out there,' the artist laughs, in what has become a moving telegraph to the future. 'You come and you fill the holes with your experience—how about that?' —[O]

1 William Pope. L. and Chris Thompson, 'America's Friendliest Black Artist', PAJ, A Journal of Performance and Art (Vol. 24, No. 3, 2002): pp. 68-72.

2 Ross Simonini, 'An Interview with Pope.L', The Believer, Issue 116, 1 January 2018.

3 Idem.