Mad Times: A Report from ArtInternational 2015

According to a report by The Art Newspaper, this year's edition of ArtInternational (which opened in Istanbul on 05 September) opened one day later and ran one day shorter because of sustained pressure from the 14th Istanbul Biennial curator, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. It was reported that Bakargiev had made "no secret of her displeasure at the coincidence of the two events opening simultaneously". Perhaps the curator felt the biennial and its artists needed sheltering from the market, but that seems a little 'nanny-state', particularly since some of the artists were showing at ArtInternational, in fantastic booths, to boot. Nikita Kadan, for instance, with a central work in the Istanbul Modern, was showing at London’s waterside contemporary. Hera Büyüktaşçıyan was not only showing with RAMPA Istanbul, but as part of ArtInternational’s artistic programme with Falling Waters, a beautiful installation in one of the Haliç Congress Center's screening rooms in which blue curtains dropped over the stage and spread out over the front row chairs.

Nikita Kadan, Procedure room (plates), 2009-2010. Print on ceramic. Courtesy of waterside contemporary, LondonNevertheless, any publicity is good publicity, and what Christov-Bakargiev imparted to ArtInternational was not only that, but a certain kind of camaraderie amongst all involved when it came to mediating the insanity not only of the Istanbul Biennial’s opening art week, but of a world in total, utter upheaval. Only recently, Turkish nationalists attacked Armenian communities in Istanbul, making the Dilijan Art Initiative’s support of Armenian artists in the biennial even more poignant; 2015 being the centenary of a genocide the Turkish government has yet to acknowledge. But despite everything, ArtInternational was good: focused yet eclectic, bold yet understated, both intimate and global (87 galleries representing 27 countries presenting works by more than 400 artists). Not a bad booth in sight, really.

Mehmet Ali Uysal, Suspended Series, 2014. Polyester, 155 x 50 x 30 cm. Courtesy of Pearl Lam GalleriesKeeping standards up was Pearl Lam Galleries, showcasing a carefully crafted stable of painters, including post-painter Mehmet Ali Uysal. Ali Uysal was also showing at Pi Artworks, which brought together works by Yeşim Akdeniz Volkan Aslan, Nancy Atakan, Horasan, Nejat Sati, Paul Schwer, and Gulay Semercioglu in a booth that perfectly balanced formal with just the right amount of irreverent. As part of the fair’s Special Projects, Galeri Zilberman showed Burçak Bingöl, Guido Casaretto, Azade Köker, and Walid Siti, who also presented a large, Tatlin-esque sculpture, The Tower, as part of the Waterside section, where a number of larger outdoor works were presented. Meanwhile, fair newcomer Victoria Miro presented works by Elmgreen and Dragset, Chantal Joffe, Idris Khan, and Grayson Perry.

Elmgreen & Dragset, He (Copper Green), 2013. Epoxy resin, polyurethane cast, metal lacquer (copper), green patinated. 190 x 140 x 100 cm. Courtesy of Victoria Miro, LondonIndeed, all the galleries that returned to the Haliç Congress Center seemed to outdo their presentations in the last edition of ArtInternational. One stand-out booth (though in truth, this gallery never fails in its installations) was Kalfayan Galleries, who put together a pitch perfect display of works by Greek artists Emmanouil Bitsakis, Nina Papaconstantinou. Tassos Pavlopoulos, Dimitris Tataris and Panos Tsagaris, whose blown up images of New York Times covers depicting riots with text boxes painted over in gold were crowd pleasers. The gallery also included works by artists represented in this year’s Golden Lion award-winning Armenian Pavilion at Venice, Hrair Sarkissian and Aikaterini Gegisian. Opposite this booth was Upstream Gallery, looking just as good with a minimal colour palette of deep forest greens, fuschias and pale pinks, articulated in a range of works by Frank Ammerlaan, Marinus Boezem, Rafaël Rozendaal, and Marc Bijl.

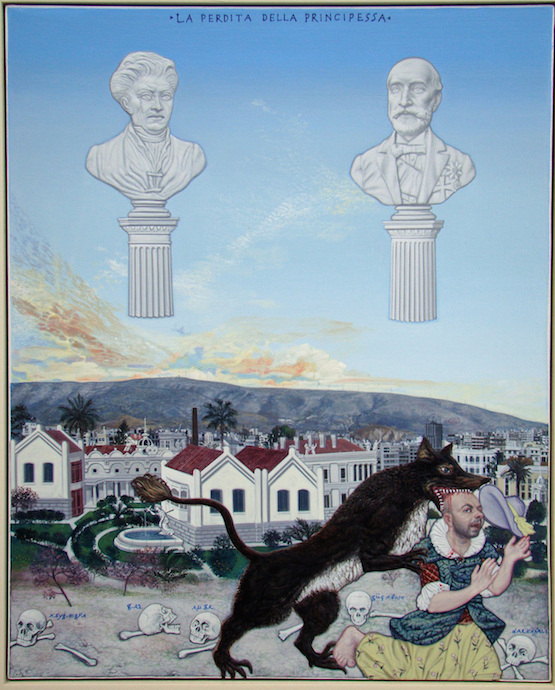

Emmanouil Bitsakis, La Perdita Della Principessa, 2013. Acrylic on wood, 31.4 x 25.2 cm. Courtesy of Kalfayan GalleriesThis year, weird was wonderful. On one walk through, I passed Patricia Piccinini’s work at Hosfelt Gallery—fantastic, bizarre, fleshy, silicone, bronze and fiberglass sculptures of flowers that seem to emerge out of bodily organs, or organisms, detailed with human hair. These were presented alongside the Australian artist’s linen canvases splattered in nipple-like circles of silicone, and beautiful ink drawings of parts of women’s bodies. Tenderpixel, an exciting new addition to the fair’s roster this year, presented a concise installation centered around Richard Healy’s The Pines, a video piece that pays its respect to the work of modernist architect Horace Gifford (1932–92), by offering a virtual tour of the Fire Island beach houses he designed; also an homage to gay cruising. Over at Barcelona gallery N2 Galería, religious iconography was taken to its absolute limits in the psychedelic, post-Renaissance future punk icons of Mario Soria, rendered in oil on canvas, often with elaborate, baroque-inspired frames produced from objects including toys brought together to form a pattern before being painted gold. The name of one work was Madonna pop Imperial.

Patricia Piccinini, Boot Flower, 2015. Silicone, fibreglass, human hair. Courtesy of Hosfelt Gallery, San FranciscoSmall was also beautiful. At a joint booth by EX ELETTROFONICA and Studio SALES di Norberto Ruggeri, Ursula Burke, Margherita Moscardini and Guendalina Salini came together with a wonderfully intricate combination of small works by Avish Khebrehzadeh, Davide Monaldi and Wolfgang Tillmans—including Burke’s Balaclava Bust made from Parian porcelain (a Neoclassical head with fabric covering its face). Yet, small doesn’t just refer to scale—intimacy was a big thing this year, too, with the design of the fair spaced out just enough between booths and sections to allow for relations to be drawn out from respectable distances (not so much a bazaar kind of fair, as a showcase). It felt intimate in other ways, too: Başak Şenova’s film programme for Videos on Stage included such names as Karen Mirza and Brad Butler, Maria Friberg, Joanna Rajkowska and Aglaia Konrad, under the title Ruins and Wounds, which explored personal histories or, quoting Şenova: “secret road maps.”

Ursula Burke, Balaclava Bust, 2014. Parian porcelain and lace. Courtesy Ex Elettrofonica, RomeIndeed, the most refreshing thing about ArtInternational this year was the deviation from the norm. There was barely a common name—or common work—in sight (okay, I did see one Abramović). Even in the historical presentations, perspectives were expanded, with such modern masters as Selma Berksoy and Ibrahim El Salahi remembered at GALERIST. At Gazelli Art House, Kalliopi Lemos proved a fair hit, no doubt in part because of Lemos receiving the Borusan Contemporary Art Collection Prize for 2015: well-deserved recognition for an artist who in 2009 brought together fishing boats found on the coast of Greece that were used by migrants to cross into Europe, and hoisted them like a totem outside the Brandenburg Gate in protest of the Mediterranean refugee crisis.

Kalliopi Lemos, Crows and Ravens, Series B #2 , 2012. Hardened plaster and mild steel. © Kalliopi Lemos. Courtesy of Gazelli Art House, LondonOne particular highlight of this fair was coming across an overview of works by Kazakh artist Erbossyn Meldibekov at the young Almaty gallery, Aspan. The works on show included Peak Communism (2009): upturned enameled metal pots made to resemble the central mountain peak in the Pamir Mountain range, once a point on the northern Silk Road positioned at the crossroads of China, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Kyrgyzstan, and which has undergone a number of name changes (Garmo Peak until 1933, then Stalin Peak until 1962, then Communism Peak until 1998, when it was renamed after the founder of the original Tajik state—Ismail Somoni). This was the perfect work for the complex space of an art fair in Istanbul: a city that, like Somoni Peak, has undergone its own historical name changes.

In all, voices were varied, different, and genuine. In the case of Nedko Solakov at Sariev Contemporary (who showed at this year’s Thessaloniki Biennale central exhibition in Greece curated by Katerina Gregos), The Water Pyramid (2008) presented an apt allegory for the fair’s context. The work features a gilded carved lime wood plaque upon which a monkey and a crocodile are also carved peering behind the plaque from opposite sides of it. On the plaque’s surface is written a story of these two creatures and their role in keeping a blue pyramid in place (a painting of which also appears in the centre of the plaque). The creatures have been carved to look behind the panel because, as we learn, they are looking for emergency solutions for an impending danger, which “may be written on the back...” You might say this is one way of looking at the story of the snake eating its own tail: an artistic gesture as a nudge, not a slap in the face (which is kind of what the 14th Istanbul Biennial felt like, by contrast).

Nedko Solakov, The WATER PYRAMID, 2008. Acrylic and black drawing on gilded carved lime wood. 47 x 68 x 8 cm. Courtesy of Sariev ContemporaryThis is interesting to think about, since ArtInternational this year actually provided some respite for visitors exhausted by Christov-Bakargiev’s manic exhibition. Of course, this could have been due to the fair’s location: right at the water’s edge, miles from the city. But it could also be due to the fact that ArtInternational seems to be taking a kind of Art-Dubai-of-the-Bosporous approach, in which the market place is treated as a space of intellectual as well as economic exchange. Take Alternatives—a section of ArtInternational “dedicated to independent art initiatives” and bringing together “prominent local and international not-for-profit spaces, independent institutions and artists’ collectives”—this year curated by artist, writer and curator Paolo Chiasera.

That a day was allegedly lost for the sake of the 14th Istanbul Biennial’s “integrity” seems to have had a minimal impact in the end. Even the publications teams, who had to deal with the mess of shipments being held in customs, were pretty chill. Ironic, isn’t it—that the openly accelerated space of the market provided respite from the contradictory machinery of a biennial? —[O]