Performance Art After Marina Abramović

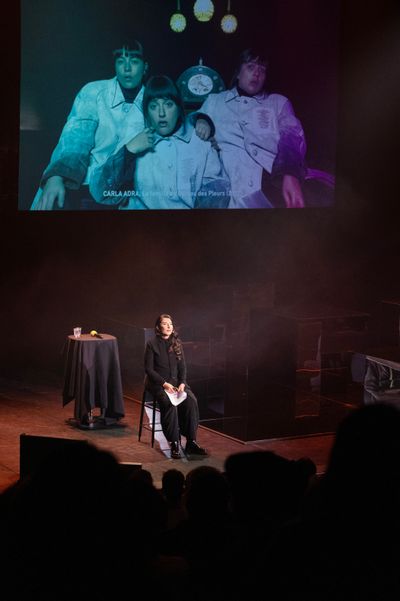

Marina Abramović at Marina Abramović Institute Takeover, Queen Elizabeth Hall at Southbank Centre, London (4–8 October 2023). Courtesy Southbank Centre. Photo: Linda Nylind.

Running concurrently with her survey exhibition at the Royal Academy, which opened in London just two weeks prior, Marina Abramović has curated an exhibition that sees her legacy revitalised through a group of artists taking a more reflective approach.

At Southbank Centre's Queen Elizabeth Hall, Abramović oversaw a series of durational performances which invited 11 artists to perform between 4 and 8 October. The exhibition is the latest organised by the Marina Abramović Institute, founded in New York in 2007 to preserve what Abramović calls a timeless art, working with artists and institutions to support performance experiences.

Among other programmes, the Institute hosts workshops on durational performances. According to Collective Absentia—one of the artists performing that evening—they are notoriously difficult.

At 76, Abramović no longer performs the pieces that earned her critical acclaim, leaving her body to much-deserved rest.

At Southbank, Abramović opened the night with a meditation of 12 breaths and three minutes of silence. The audience of some 600 visitors was then left to explore the front and backstage, lobby, and greenroom, where the 11 performers were spread, serious expressions on their faces recalling Abramović's own commitment to the art form.

I walked to the lobby, where a hooded figure was seated on a chair centred within a section of the floor delineated by a black perimeter. The artist known as Collective Absentia remains anonymous as they perform silent protests against Myanmar's oppressive military rule and armed clashes, which have escalated since the coup of February 2021 and protests led by the pro-democratic movement.

Collective Absentia, who currently lives in Myanmar, shared in an earlier conversation that they had watched friends take up arms but refuses violence as a counterpoint to violence. It's a quiet form of resistance, an approach favoured by several of the artists performing that evening.

This call to quiet reflection was observed steps away in Yiannis Pappas' The Key (2023), first conceived by the artist in response to the migrant crisis in Greece. Imprisoned inside a rectangular box divided into six, the artist carved his way through over five days with a simple key. The final door, however, needed to be opened from the outside with the same key.

'How will they know to take the key from you?' I asked Pappas in his dressing room earlier, nodding to the holes aligned at the bottom of the box, which allowed audiences to drop in food or objects for the artist. 'Maybe they won't,' Pappas replied, speaking to the role of chance within his performance, which subtly invited audience engagement.

I returned in the final hour to leave a fruit bar for the artist. When I later revisited the site, water bottles had replaced the fruit bar. It was a gesture that recalled the human instinct to alleviate suffering, despite an initial barrier of unfamiliarity that might otherwise limit a participant to passive onlooking.

In an inversion of The Key, Despina Zacharopoulou asked visitors to sign a contract agreeing on the time they would spend in a closed room with her, as part of Dokimi/Essay/Essai (2023). The performance sought to see whether people would keep to their promise, but arriving at the unmoving queue during the final hour, I decided against it.

The process recalled the lines that threaded down New York streets in 2010, as people waited—sometimes for hours—to sit in front of Abramović herself in the artist's seminal retrospective at MoMA. Just as some patiently waited for Zacharopoulou in the hopes of arriving at a worthwhile revelation, the refusal of others to find out perhaps translated to a lack of faith.

Also recalling Abramović, Aleksander Timotic's Are you hungry? (2023) showcased a softer variation of the artist's 1997 Venice Biennale Golden Lion performance, Balkan Baroque. In Abramović's work, the artist scrapes away at 1,500 bloody cattle bones while singing folk songs from her childhood in Yugoslavia.

Timotic, an artist and opera singer, invited audiences to peel potatoes at a round table in the lobby. He executed the task with a dejected expression, rising at intervals to sing heartfelt ballads from the Balkans, where song is a means of catharsis and love is better expressed through nourishment.

Interjecting the artist's harmony were voices from the disjointed chorus of Carla Adra's Goodnight Daisies (2023). Seven identically dressed performers roamed around narrating the struggles and traumas of strangers. The act meant to replicate the fluidity of individual experiences, but bore an uncanny resemblance to the cacophony of voices already resonant within an attention economy.

Along a corridor backstage, Paul Setúbal's Because the knees bend (2018–2023) saw the artist smashing a rubber baton against the walls to replicate the impact of violent acts around the world. But something about the piece seemed to amplify the privilege of cities where violence and armed conflict can be presented as hypothetical sensorial experiences.

Other realisations were less severe, speaking more to the experience of attending a durational-performance exhibition than the implications of enacting the political body today. It was a pleasure to see the front and backstage merge over the four-hour takeover, which transformed the site into an evolving performance itself.

There were unexpected run-ins, including once with Abramović, who walked out from a dressing room backstage at 7:05pm and requested a car to leave, and twice with trans artist Cassils, who was rushed to their dressing room dripping from prolonged contact with the neoclassical ice torso that was the key object of their performance.

For their last live performance before undergoing gender-affirming top surgery, Cassils melted solid ice torsos on their own exposed chest. Tiresias (2023), a performance repeated across three days and totalling approximately 12 hours, is named after the blind prophet of Thebes in Greece who was transformed into a woman for seven years. Cassils stood entirely nude inside a large, transparent box in which the melting ice pooled, in a symbolic performance that spoke to endurance and metamorphosis. In the absence of the artist, the ice sculpture glimmered on stage in a gesture toward new beginnings.

Theatrical presentations by Carlos Martiel and Miles Greenberg were held inside the main auditorium, filled with a thin layer of smoke. A spotlight was cast over Martiel's nude body, which was raised on a central podium and tied to a pole with rope. A Union Jack raised behind him referenced historical oppression and violence by Britain against former colonies.

Momentarily beautiful but edging toward spectacle was Greenberg's Water in a Heatwave (2021) on the central stage, where performers were positioned in pairs above five reflective podiums. Following the broken cadence of a thunderous soundtrack, they pressed against one another with their hands interlocked, taking up a series of hesitant and careful postures.

Greenberg makes tableaux vivants [living pictures], which perhaps explains the awkward movements. However, the staging—complete with glimmering nude torsos and white-out lenses—was quickly betrayed by the lack of exertion in the musculature of performers, dissolving any intent to create tension in the space through the clashing bodies.

Inside a large storage room backstage, Paula Garcia had just concluded her performance. Metal fragments and nails were scattered all around, covering most of the central platform. A full suit of armour was separated into individual parts on the ground, with Garcia and her three assistants sorting through the pieces. Twenty minutes later, two neat piles suggested the process was over. Garcia paced for another five minutes, then stretched.

In a privatised and hurried city like London, to create time and space to think can be a radical gesture.

Garcia's projects have sought to show the invisibility of blue-collar labour by performing physically demanding tasks herself, with the process becoming part of the artistic product. It is unacknowledged work that recalls that of an artist—Abramović herself was never paid for the hours spent preparing her body, only the hours of her presence.

In Garcia's actual performance, the artist wore magnet armour and stood against a metal sheet. Her collaborators threw metal debris at her until she was fully covered. It was an effective piece in replicating the production-bound body as a site of conflict. Thunderous cacophonies filled the room in waves as the artist became the receptacle of industrial debris.

Inside a small room backstage, Sandra Johnson's close to the close (2023) presented an act of extreme concentration. Surrounded by audiences seated an arm's length away, the artist manipulated a black bead between her fingers while seated on the edge of a chair. Her legs shook momentarily, but her gaze did not waver. It recalled the commitment and erasure of the self Abramović's work evokes, manifested in the next generation.

At 76, Abramović no longer performs the pieces that earned her critical acclaim, leaving her body to much-deserved rest. Instead, she allows her works to be performed by others and channels her energies into the Institute to build upon the legacy of her five-decade career.

In the artist's current survey at the RA, a heated doorway frames two nude performers performing Imponderabilia (1977/2023), while the performers hanging by a bicycle saddle for Luminosity (1997/2023) are rotated at 30-minute intervals in accordance with labour laws. Therapists are available to all performers, suggesting these are indeed different times.

Shared as archival content are more radical performances such as Rhythm 0 (1974), for which the artist invited audiences to use a spread of 72 objects on her—including a rose, feather, knife, and gun—which resulted in her skin being cut and a gun held to her head. It was a seminal work that revealed the darker side of humanity in a microcosm without accountability for violent acts.

What then becomes of performance art in an era that no longer endorses the mental and physical intensity known to Abramović and her counterparts in the 1970s?

At Southbank Centre, what emerges from performers working within the constraints of keeping both themselves and audiences safe are the realities of a world that is much more careful about how people behave and relate to one another, where reflection can stand in for action and onlooking is possible without involvement. But in a privatised and hurried city like London, to create time and space to think can be a radical gesture. —[O]