Taipei Biennial: Planet Earth Defence Command

Like the Earth itself, the debate about what to call the current geological epoch is getting heated. For 11,700 years, since the end of the last ice age, we’ve been living in the Holocene, the temperate climate in which human civilization has thrived. But Nobel Prize-winning chemist Paul Crutzen argues that now mankind has become the most significant driver of environmental change, it’s time for a name that better reflects our influence. He suggests “the Anthropocene”.

Geologists have to point to a permanent change in the rock strata to define a new epoch, and there’s disagreement about whether the beginnings of agriculture, the industrial revolution or the nuclear age is the best candidate, and if any of them is sufficient. But no-one is disputing that humans have made lasting changes to the planet, and our impact is only increasing. These facts have already entered cultural rhetoric, as evidenced by the provocative and revelatory 2014 Taipei Biennial.

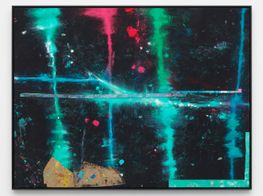

"The Great Acceleration: Art in the Anthropocene" is curated by Nicolas Bourriaud (b. 1965), the director of the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, and, it turns out, a planetary champion. He conscripts an impressive militia of 52 artists to document and imagine a defence against the ways in which human-initiated systems are getting out of our grasp. Unabated economic growth is consuming scarce resources; the impacts of climate change are becoming more severe; and there are now more spambots and other automated agents online than there are human beings.

The scene of Bourriaud’s uprising is the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, a collection of stacked white boxes assembled in 1983. The museum is located near the Keelung River in Zhongshanmeishu Park, a laid back locale with a high blood pressure past—from 1955-1979 it was home to the United States Taiwan Defense Command.

Bourriaud’s own defense is billed with the tag-line: “a tribute to the co-activity amongst humans and animals, plants and objects”, with objects in particular enjoying special status in “The Great Acceleration”. In Jet Air (1970), Swiss artist Peter Sämpfli renders utilitarian old tires in oil paint, blowing them up to the size of royal portraits. Meanwhile Korean artist Haegue Yang creates a kind of anthropology of assembled commodities in her series Medicine Men (2010) and Female Natives (2011), coat rack skeletons covered in wigs, cables, light bulbs and house plants. She gives these things the same status as human beings but also weighs them down with the same cultural baggage we give to exotic others.

Inga Sala Thorsdottir and Wu Shanzhuan go even further in their work Thing’s Rights (1994), annotating human rights documents to endow ‘its’ with the same inalienable privileges usually given only to ‘hes’ and ‘shes’. This seems satirical, a parody of our reverence for products, but it also reminds us of the limitations of that reverence: we throw away the things we once lusted after once we lose interest, and our waste has no recourse for its maltreatment.

Instead of giving products the status of people, Taiwanese artist Huang Po-Chi makes himself and his participation in biennials part of a globalized production chain. He first had the fabric for denim shirts cut out during the 2014 Shenzhen Sculpture Biennial before installing a sewing machine where they could be finished at the Taipei Biennale.

Surasi Kusolwong, from Thailand, also delves into textile manufacturing in his work Golden Ghost (Reality Called, So I Woke Up) (2014), hiding 12 gold necklaces for visitors to take home in five tons of industrial thread waste. The deep piles of tangled thread are incredibly heavy, and sifting through them, starting to sweat, one thinks of not only capitalism’s massive hunger for materials but also the incredible human toll of overproduction.

Even the byproducts of manufacturing, the collateral damage of capitalism, are given the status of subjects in the exhibition. This is evident in Belgian artist Peter Buggenhout’s The Blind Leading The Blind series (2014), assemblages of industrial-sized junk, covered in grease and dust, that come to life with their own anatomical integrity, like mammals of manufacturing. Marlie Mul’s resin Puddles, which perfectly resemble a pool of rain gathered on a bitumen highway, likewise become forms worthy of study and admiration.

Argentinian artist Mika Rottenberg’s Bowls Balls Souls Holes (2014) video is perhaps the biennial’s best commentary on how little contemporary economic, communications and physical networks yield to individual comprehension. Inside a Harlem bingo hall, random numbers are generated by a psychic network connecting a man attaching colored clothes pegs to his face, a woman giving herself a clothes peg pedicure, and a worm hole that opens onto polar waters. The absurdity of the work resonates in Vietnamese-American artist An-My Lê’s documentary photograph series Events Ashore (2005-2014), in which she navigates webs of bureaucracy to visit US naval ships performing mystifying services in the Arctic and Antarctic.

A large part of the exhibition is concerned not only with reappraising the increasingly alien and alienating world we find ourselves in, a place we’re remaking in unintended ways, but with following tentacular trends deep into inky futures.

Jonah Freeman and Justin Lowe’s Floating Chain (Fake Wall) (2014) is a future world hidden behind an ersatz recreation of the biennial’s own offices. The cubicles have been turned over to the Sansan International Corporation (on their business cards: “Neo-Realist Liars / Revenge Magik / Rural in Reverse), whose ambiguous activities require familiarity with the Vortice Science of Behavior manuals, whose bizarre titles include The Fedex Monster and Suits in Cheap Sunglasses. Behind the office is a concealed entrance to The Octopus Spa, a vision of future hedonism rendered in massage chairs, semi-pornographic beach towels and a bubbling Dracula mask fountain.

Other future scenarios in the biennial see human beings’ status in the natural world being overthrown. Vanuatu-born artist Gilles Barbier’s mixed media sculptures Still Man and Still Woman (2013) depict people being swallowed by vegetation. In Ching-Hui Chou’s Animal Farm (2014) series of photographs we see humans in typical habitats—bed rooms, gyms and lounges—that have been recreated as zoo enclosures. These specimens are presumably being kept because life in the civilized wild has become untenable. Who the zookeepers might be is left ominously unclear.

The audience for this compelling biennial, however, is obvious. While there is a fair representation of Taiwanese and other East Asian artists included, the exhibition is powerfully relevant to human beings worldwide, and to animals, plants and objects too.—[O]