Bharti Kher's Atlas Series, Surveyed

In Bharti Kher's 'Atlas' series, colonial cartographies become sites of global counter-narratives, appropriated to restore the presence of bodies in representations that are normally emptied of them.

Exhibition view: Bharti Kher: Misdemeanours, Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai (11 January–20 April 2014). Courtesy Rockbund Art Museum. Photo: Yan Tao.

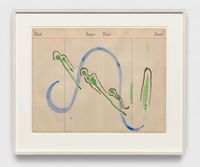

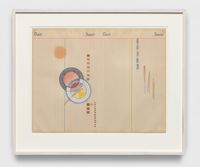

'Atlas' was born out of the artist's research into the Great Trigonometrical Survey, initiated by the British in the 1800s to scientifically measure the entire Indian subcontinent. The series was first developed for Misdemeanours, the artist's first solo exhibition in China at Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai in 2014. In Western Route to China (2013), four maps taken from an Éditions Larousse Atlas published in 1947 are covered with bindis, which Kher has used throughout her practice as both motif and material. In one map titled 'East Indian Archipelago', yellow spots mark out sea routes to China taken by the East India Company, their line building up against arrows moving through the land towards the coast.

Among these cartographies were seven antique globes positioned on stools of differing heights, forming the installation Not All Who Wander Are Lost (2009–2010)—a title also used for the public art project that Kher developed while in residence at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston in 2016, which expands on the 'Atlas' series. Here, an enlarged map from The Larousse International Political and Economical Atlas published in the 1960s was installed on the museum's façade, its contours and masses lined with orange and black bindis, referencing the movement of peoples between Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.

Kher has talked about the bindi, in Sanskrit bindu, meaning 'a drop' or 'a small particle', as a representation of the third eye, and how its presence on these maps represents eyes looking outwards. This broad reversal of the gaze—in which the plotting of a route is replaced by what Kher describes as the marking of 'human positions', 'remnants of memory', and 'residues of the soul'—speaks to the artist's disruption of the map's formal grid and its geodesic abstractions.

A playful and vibrant fluidity dominates these populated compositions, their atomic elevation opening up a vision of earth as a site of absolute, sublime flux.

The Larousse Atlas, after all, employs the cartographic conventions devised by Gerardus Mercator in the 16th century, which remain in common use today. The globe is represented by a flattened cylindrical projection, with a grid that spaces further apart as the distance from the equator increases. The result is a distortion of scale that makes landmasses like Europe and North America appear disproportionately large, which in turn underpins hierarchies of global space that conventions of map-making have so often reinforced.

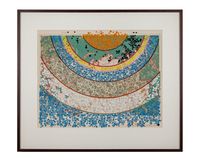

In response, Kher reclaims mapping's formal measurements by upholding the organic realities of changeable, material space: a world constituted of many worlds, defined by the living entities that move through and shape it. Some maps in the 'Points of departure' series, for instance, involve sperm-shaped bindis arranged in a series of swirling spirals that move across the surface, as is the case with Points of departure II (2018). (Apparently, when Kher came across a woman wearing these bindis, she found out where she bought them and acquired the shop's entire stock.)

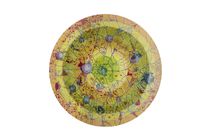

In other instances, Kher adopts the language of formalism to highlight the abstract, organisational structures that are applied to lived bodies, spaces, and representations alike; in Points of departure V (2018), the cylindrical grid marking the top of a globe is applied to a map titled 'Heavy Industries', with scant glimpses of the original document peeking through constructivist lines and meridians marked out and filled in by different coloured dots.

A playful and vibrant fluidity dominates these populated compositions, their atomic elevation opening up a vision of earth as a site of absolute, sublime flux. To quote the artist, 'My maps are sometimes entries into the spaces of losing yourself as they go nowhere and everywhere'—a condition that seems to fit with the context in which the 'Atlas' series is being surveyed for the first time: Perrotin's online Viewing Salon. 'I think the online platform is perfect', Kher notes; 'The maps will get lost in the web of information and coding and then something else will just wash over your mind and they fade away.'

Kher is right. While her maps really do lend themselves to virtual viewing, they are somehow lost in the format. Users are presented with a page where installation shots from past institutional shows intersect with individual work tiles along with prices and 'inquire' buttons, some quotations, and a (great) video interview. While there are beautiful close-up shots of specific sections alongside some works, the option to zoom in on individual pieces feels clunky, and does not always render the sharpest view—the information on the map in Western Route to China, for example, is hardly discernible, with only one of the four maps originally shown in Shanghai presented.

Ultimately, this portfolio-style presentation succeeds as an introduction. But the noise of business and commentary means there is little to differentiate this page, described as an online exhibition, from an artist's section on a gallery website or virtual selling platform. This is a shame given the potential for how these maps, in all their vibrant complexity, might have creatively intervened in the online space, itself a navigational and 'worlding' tool, in the same way that Kher's bindis interfere with historical renderings of earth.—[O]