In his ongoing 'Ecriture' series of paintings, conceived in the 1960s, Park Seo-Bo strived for tranquility and meditation through repetitive actions. Park was also a long-time educator and leading Dansaekhwa artist recognised for his contributions to the history of modern and contemporary Korean art.

Read MoreComing of age in the 1950s, Park Seo-Bo was among the young artists who reacted against Kukjeon or the National Art Exhibition system that then dominated the Korean art scene. Against what he perceived as the homogenising academicism of Kukjeon, Park began to explore ways of incorporating elements of abstraction—freshly arrived from North America—and unconventional techniques, thus paving the way for abstract art in Korea.

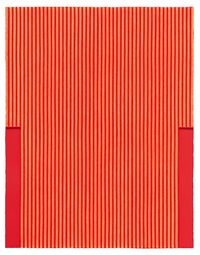

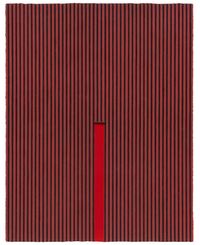

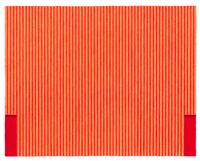

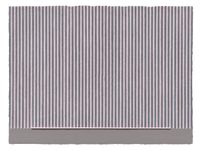

Primarily working with Korean paper (hanji) and canvas, Park Seo-Bo developed a method of manipulating gesso or paint while the surface is still wet. In his early 'Ecriture' works, the artist used a pencil or a stylus to make repetitive marks; since the 1980s onwards, he has often applied paint to hanji or pushed around its pulp to create uninterrupted spaces.

While influenced by North American Abstract expressionism and Minimalism, Park's paintings are not an uncritical absorption of outside influences but a negotiation between the traditional and the new. Myobop—as 'Ecriture' is known in the Korean language—translates as 'law of drawing', which references Taoist and Buddhist philosophies. Also known as 'the journey of the hand', works belonging to the 'Ecriture' series eliminate individual gestures through repetition and enters a meditative state.

Parallels can be drawn between Park Seo-Bo's 'Ecriture' and the work of his contemporaries, including Lee Ufan, Chung Chang-Sup, and Kwon Young-Woo, who also often employ monochrome colour palettes, humble materials, and repetitive gestures. In 2000, curator and scholar Yoon Jin Sup coined the term 'Dansaekhwa' or Korean Monochrome Painting to consider their work collectively. Today, Park is regarded as a founding figure of Dansaekhwa.

'Ecriture' has experienced stylistic changes over the years. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Park Seo-Bo worked primarily with black and white, two of the most important colours in East Asia philosophy: black represents time and pure emptiness; white alludes to death, spirituality, and the void. In his interview with Ocula Magazine in 2018, the artist said that he began to use 'colours that heal' in the 21st century in an attempt to create paintings that restore peace in the contemporary world of rapid and drastic changes.

Park Seo-Bo has led an impressive career as an educator of art in South Korea. Between 1962 and 1994, he taught at Seoul's Hongik University—one of the most prestigious institutions of art in Korea and his alma mater (from which he graduated in 1954). In 1986, the artist became the Dean of the College of Fine Arts, a position he held until 1990. Park continues to support young Korean artists and contemporary Korean art on the international art scene through Seo-Bo Art and Cultural Foundation, founded in 1994.

Park Seo-Bo began to receive international recognition around 2014 with the rise of renewed interest in Dansaekhwa. His paintings have appeared in seminal exhibitions of the movement, including When processs becomes form: Dansaekhwa and Korean abstraction, the Boghossian Foundation, Brussels (2016); Dansaekhwa and Minimalism, Blum & Poe, Los Angeles (2016); and Dansaekhwa, a Collateral Event of the 56th Venice Biennale (2015).

In 2019, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul organised Park Seo Bo: The Untiring Endeavorer, a major retrospective exhibition of the artist's career. In March 2021, White Cube Bermondsey, London, presented a large solo exhibition of Park's work.

Park Seo-Bo Art Museum

Park Seo-Bo died on 14 October 2023. Among his ongoing projects had been an art museum in his name, which will be completed and open to the public on Jeju Island in 2024.

Sherry Paik | Ocula | 2023