As a progenitor of the Japanese Mono-ha, or School of Things, movement, Lee Ufan led a loose constellation of artists who championed the use of ordinary materials during the late 1960s, significantly altering the course of 20th-century Japanese art. Lee's dense yet poetic text, Beyond Being and Nothingness—A Thesis on Sekine Nobuo, provided something of an intellectual foundation for the movement. The group eschewed representation, choosing instead to zero in on the relationship between perception and material. Its main aim—as expressed by its key figures—was to demonstrate the fluid coexistence of objects, ideas and encounters.

Read MoreIn 1956, Lee began studying painting at the College of Fine Arts at Seoul National University, but after two months he relocated to Yokohama, Japan, where he went on to earn a degree in philosophy in 1961. During this period, the restrained painting style of his student work was in formal and conceptual opposition to the free expression of Gutai—the performance-oriented post-war Japanese art movement that anticipated Fluxus and inspired the work of Yves Klein, Allan Kaprow and Nam June Paik.

In the mid-1970s Lee became one of the major exponents of Korean Dansaekhwa ('Monochrome Painting')—a style that became one of the country's most important artistic developments in the 20th century—and the first from that period to bring the movement to Japan. Lee, along with the group's other loosely connected members, emphasised materiality as a means of producing relationships that link objects to viewers. In the repetitive gestural marks of his work, abstraction served to register the body's movement as well as the passage of time. With an eye towards modernist abstraction's best-known devices—seriality, gesture, grids and monochrome—Lee's paintings pushed the bounds of formalist paradigms. And through their affinity to and correspondence with Euro-American art, they proffered new forms of connection across seemingly incompatible ideological positions.

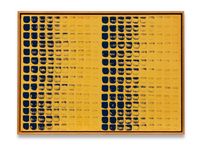

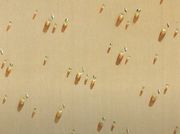

In his early painting series, 'From Point' and 'From Line' (1972–84), Lee combined ground mineral pigment with animal-skin glue, typical of the traditional Japanese Nihonga painting in which he had trained. Each fastidious brushstroke consisted of multiple simultaneous layers, and where the brush had first made contact with the support, the paint was thick, creating a 'ridge' that would gradually lighten. Rarely did Lee's brush touch the canvas separately more than three times, yet this economic application created a feeling of dynamic tension between gesture and picture plane characteristic of his paintings. In the early 1990s, Lee carried this through to his 'Correspondence' paintings, which consisted of a minimal number of grey-blue brushstrokes, applied on large white surfaces.

Lee's more recent and ongoing 'Dialogue' series, begun around 2006, considers philosophical notions of emptiness and fullness. These exist within a lineage of work that dates back to earlier works such as the 'From Line', 'From Point' and 'From Winds' series, which in the 1970s marked his transition from relatively small strokes predominantly in blue and orange to the intermixing of those colours and the predominance of grey tones from the 1980s.

Today Lee views his pristine white supports, enlivened by touches of paint, and his large site-specific sculptures made from stone and iron as materially opposed to the virtual nature of screen-based media that has now become so ubiquitous.

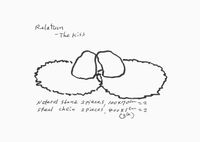

Although he is highly regarded as a painter, one of Lee's best-known series is 'Relatum' (1968–), three-dimensional groups of rocks dispersed with industrial materials such as steel sheets, glass panes and rubber. Lee began producing them as a response to 1960s Japan and its intensely turbulent socio-political climate. In each of these assemblages, the artist emphasises how constituent parts sit in relation to one another, to space and to surrounding objects, going beyond the enclosed network that is implied by the term 'sculpture' and its more conventional examples.

As well as being the recipient of numerous awards and honours, Lee is also represented in numerous prominent collections around the world. These include The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Tate Modern, London; The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto; and The National Museum of Art, Osaka.

In 2010, the Tadao Ando-designed Lee Ufan Museum was opened at the Benesse Art Site on the Japanese Island of Naoshima, dedicated to the artist and his legacy. Lee—a professor emeritus at Tama Art University, Tokyo, where he taught from 1973 to 2007—divides his time between France and Japan.

Tendai John Mutambu | Ocula | 2018