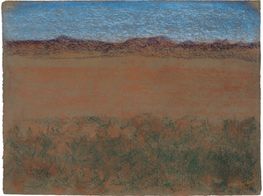

Bob Monk

Bob Monk. Courtesy Gagosian.

Bob Monk. Courtesy Gagosian.

Born in 1923 to European immigrants in Washington D.C., Richard Artschwager is a sculptor and painter known for his enigmatic and idiosyncratic style that straddles various movements, yet belongs to none. He studied biology and mathematics at Cornell University and, after a stint in the army in World War II, pursued art as an interest while supporting his family with day jobs that included baby photographer and furniture maker. Both jobs were to leave a mark on his artistic career, which reached a turning point in 1964 when he took part in a group exhibition at Leo Castelli Gallery alongside Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol, among others. His first solo show with the gallery took place a year later.

The late 1960s were an especially prolific decade for the artist, not only because of his career breakthrough with Leo Castelli, but also because of the invention of a visual repertoire that he developed for years to come. The most important visual staple he created during this period was arguably the 'blps' (pronounced 'blips'): simple monochrome ovals with two parallel sides he deployed in different media, which he developed during a teaching stint at the University of California at Davis between 1967 and 1968.[1] Artschwager planted dozens of these shapes—in the form of reliefs, stencils, or decals and using materials from wood to rubberised horsehair—inside museums and in open urban sites in the late 1960s and 1970s. He has said that the sole purpose of his 'blps' was to bring attention to what is around us, and these elongated dots certainly excel at catching the eye by stealth.

Artschwager considered his 'blps' analogous to punctuation marks, a theme that he repeatedly explored in other mediums. From the mid-1960s to early 2000s, he rendered exclamation marks in a range of materials and colours, from fluffy plastic bristles to steel hardware. When he began to use the mark in 1966, the comic-strip convention of graphic mark exaggeration was common in Pop Art, but he distanced himself from this pop exuberance in his early punctuation works by making object-sculptures that were closer to the Minimalist idiom. His late sculptures deploying the exclamation point are often of loud colour and to human scale, typified by the fluffy yellow Exclamation Point (Chartreuse) (2008).

Artschwager also developed a fascination for domestic objects, especially furniture, in the 1960s. His first sculpture, Portrait Zero (1960), like many of his works to come, drew inspiration—according to the artist's account—from a children's TV programme he saw, in which a man chastised his son for piling wooden stacks haphazardly. In response, Artschwager hammered together a stack of plywood boards in a similarly slapdash fashion, and his famous furniture-sculptures began demonstrating the finesse of the cabinetmaker, despite retaining a cobbled-together, homespun quality. New and cheap materials entered into his practice, such as Formica and Celotex, a rough-textured fibreboard commonly used on ceilings. (Like Gerhard Richter, many of Artschwager's paintings on Celotex reduce the resolution of photographic sources to the point of blurring the figures.) Description of a Table (1964) is a cuboid plywood structure inlaid with black, white, and faux-wood grain Formica that gives the illusion of a tablecloth that 'drapes' over the cube's brown surface, with the black panels beneath appearing like empty space. The work pares down an object of daily reality—not just a furniture object but also its attendant space—to its simplest geometry with a cartoonish accent.

In the mid-1970s, Artschwager gave up his workshop studio, returned to the practice of drawing, and discovered the six objects—the door, window, table, basket, mirror, and rug—that would become his obsession until his last major artwork, an installation called Six in Four (2013): four immersive installations inside Whitney's elevators of one or more of the six motifs, where visitors enter to find themselves under a table or in front of a mirror. The artist remarked that he 'played' these six objects like he played the piano as 'some kind of fugal exercise'. One 1974 drawing, Door Window Table Basket Mirror Rug #10, is made up of atomised short lines that appear to ascend, descend, swell, and thin at the same time.

The balance between coherence and dissipation in Artschwager's work points to a perceived fragility of pictorial information: a theme that preoccupied him throughout his career, including the period shown in his latest exhibition at Gagosian's 980 Madison Avenue space in New York, Primary Sources (16 January–23 February 2019). Curated by Gagosian's director, Bob Monk, the show presents paintings and drawings alongside source materials from the artist's personal archive, spanning the 1960s to his death in 2013, for the first time. In this exhibition, Artschwager's distressed imageries are on ample display, and their juxtaposition with relatively clear source materials—usually clippings of contemporary news—illuminate the artist's departure points, which Monk elaborates on in this conversation.

TDA late bloomer, Richard Artschwager held his first solo exhibition at Leo Castelli Gallery in 1965 at the age of 42. Could you give us a sketch of his artistic education, be it formal or informal?

BMArtschwager's mother was an artist, so he was exposed to art from a young age. Artschwager pursued his formal education not as an artist, but as a scientist at Cornell University. His university education was interrupted by World War II, in which he served as a solider and later as a counter intelligence operative—he spoke German fluently. After the war, Artschwager moved to New York and studied with artist Amédée Ozenfant at the Studio School between 1949 and 1950. At the time, Artschwager believed that all the possibilities of visual art had already been exhausted and he had nothing new or of value to contribute as an artist. He then turned to furniture-making and established a workshop that produced custom furniture of his own design.

When a fire destroyed nearly all the contents of his workshop, Artschwager started to experiment with the scraps of wood and other remnants and produced non-utilitarian compositions and eventually art objects. After garnering some recognition in sculpture, he expanded his art-making to painting and drawing.

TDIt is noted that Artschwager worked frequently with synthetic materials, such as Celotex, whose rough surfaces retain the painterly trace well. In his work, he also achieves a 'slow' aesthetic whereby broken figural elements dissolve into abstract brushstrokes across a range of works on paper and panels—a distressed aesthetics of a world under enduring pressure. Could you tell us more about the artist's process and his distinctive style?

BMArtschwager first turned to Celotex because he was fond of the texture, which looks like the fibres of handmade paper magnified on a larger scale. He primarily used this material as his painting support. When Celotex stopped being manufactured with its characteristic texture and patterns, Artschwager produced his own fibre panels to paint on. The rough surfaces abstracted and fractured his compositions in unexpected ways. The fractured imagery encourages close looking and deep engagement with the work. For example, Train Wreck (1968), when viewed up close, has an almost impressionistic look due to the brush strokes on the textured surface. With a few steps back, the imagery comes more into focus.

Artschwager's distinctive style is inherently connected to his choice of unconventional materials. At the beginning of his career, Artschwager's use of Formica influenced the aesthetic quality of his furniture-like sculptures. Rather than using expensive wood or other valuable materials, Artschwager was drawn to Formica as it is a material and also a photographic image of another material. Celotex and fibre panel also greatly influenced his painting style due to the distinctive uneven surface.

TDYou have just curated an exhibition of Artschwager's work paired with archival material sourced from his archive, Primary Sources, at Gagosian in New York. How did the idea for this show come about?

BMAfter Artschwager's death, Gagosian undertook the project of organising and archiving, both physically and digitally, all of the ephemeral materials from his studio. The materials arrived without any organisational method. Gagosian staff sorted through and categorised everything by theme and material classification. Everything was then digitally scanned and packed. The materials mostly comprised clippings, which Artschwager took from newspapers and magazines. In some cases, he drew a grid for enlargement of the found image onto the surface of his painting support.

Also included were original sketches, un-gridded clippings, whole pages, and articles from exhibition catalogues, magazines, newspapers, and brochures. There were many photocopies of drawings or news clippings, which Artschwager used to work out different options for cropping and composition. Personal photography was also included in the studio materials. Many of the photographs were taken in the studio, and others are of subjects that appear in his paintings, drawings, and sculptures.

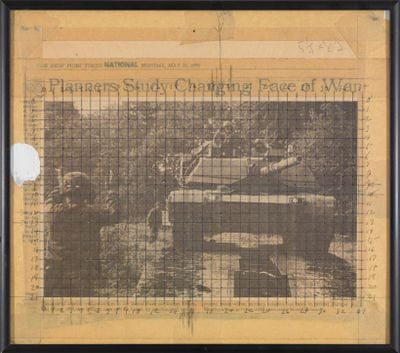

While looking through all the contents of this archive, right away some of the materials were recognisable as sources for the specific artworks by Artschwager. For example, there was a clipping with an image of a tank from the 21 May 1990 issue of the New York Times over which Artschwager drew a gird to enlarge the image. This clipping is the source for his painting Tank (1991). After in-depth research, we developed the concept for Primary Sources, which would display Artschwager's source materials with a selection of corresponding artworks to highlight an intimate and little-seen aspect of his working process. On display are the source materials for the paintings Chandelier I (1976), Excursion (2002), Osama (2003), and numerous other works.

TDSince the early 2000s, Gagosian has held a number of major Richard Artschwager exhibitions across New York, London, Beverly Hills, among other locations. How does this exhibition fit into this genealogy?

BMThe previous exhibitions of Artschwager's work held at Gagosian concentrated on the artist's recent work. After his passing, we were allowed a window into his private studio life, which we aim to illuminate in this exhibition.

TDThe events that Primary Sources focus on seem to tend towards moments of rupture—could you talk about the histories that Primary Sources deals with?

BMArtschwager did not inflect his chosen imagery with his own values or opinions, which allows them to remain open to infinite interpretations. Many of the scenes that Artschwager chose to paint, and which we chose to include do, however, still resonate with social and political poignancy today. Current events did not influence the selection. The selection was influenced by the artist's source material.

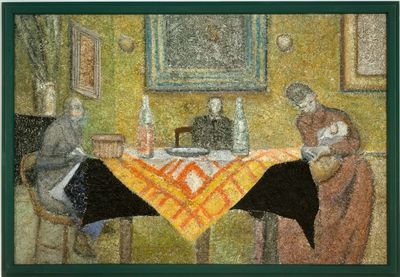

That being said, many of the works in the show contain imagery that does not connote rupture, such as the paintings depicting lavish interiors or works inspired by Tintoretto or Vuillard. The selection of works in the show spans most of Artschwager's artistic career. All the works correspond to source materials found in the artist's archive.

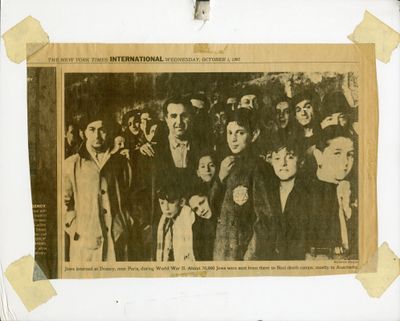

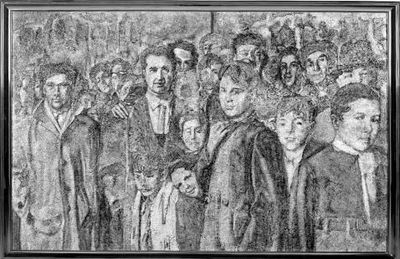

TDYou have highlighted an important strand in this exhibition in your reference to Tintoretto and Vuillard: Artschwager's engagement with art history. For example, the source image for Night Watch (1999) is included in the show. Artschwager reproduced a World War II photograph of Jews interned to be sent to Nazi death camps, but the composition is reminiscent of Rembrandt's 1642 painting. What are we to make of the links that he forges between art histories and histories of trauma?

BMArtschwager's titles are often as interesting as the visual tropes he used. Artschwager's Night Watch (1999) is not on view in our show, however the source material for this painting is. What Artschwager's painting has in common with Rembrandt's is the title, not the composition. Whereas Rembrandt's Night Watch is a celebratory scene, Artschwager's work acknowledges a history of suffering.

In other works, Artschwager did mimic compositional elements of art historical paintings. For example, his 1969 painting Tintoretto's 'The Rescue of the Body of St. Mark' was inspired by Tintoretto's 1562–1566 masterpiece, which now hangs at the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan. With the exception of St. Mark's outstretched hand, Artschwager replaced all the figurative elements in the original painting with geometric shapes and his signature 'blp' form.

Artschwager was exposed to visual art from a young age. The art historical references in his own work were likely inspired by artists and specific artworks he admired. The historical events that he chose to render were sourced from found images.

TDWhat is striking about Primary Sources is how it shows Artschwager's gravitation toward charged imageries of the military, such as the images of Pearl Harbour. Yet, his earlier works do not typically feature such overt political content. What inspired this turn?

BMArtschwager served in World War II, and fought in the Battle of the Bulge. Perhaps he did not want to engage with military imagery in his art while his own experiences and memories were fresh. Later in life, the imagery of tragic events highlighted in the media, became more prevalent in his work.

The composition of Artschwager's painting Arizona (2002) was inspired by a well-known photograph of the bombing of the battleship U.S.S. Arizona at Pearl Harbour in 1941. Although the attack occurred just short of Artschwager's 18th birthday, he painted this traumatic scene over half a century later. The image Artschwager referenced for this work was published in an issue of the New York Times from 2002. The article accompanying the image highlighted parallels between the lack of military preparedness at Pearl Harbour and the terrorist attack of 11 September 2001, 60 years later.

The source image of Tank (1991) comes from an image reproduced in the New York Times in 1990. The accompanying article explains that the image depicts the U.S. army engaged in a military exercise. It is possible that the artist's wartime experiences may have informed his interest in certain subject matter and imagery for painting. In other cases, such as his paintings of Timothy McVeigh, the horror of the Oklahoma City bombing and the widespread public shock and revulsion of this tragic event provoked Artschwager to paint this controversial subject. —[O]

—

[1] 'Richard Artschwager: New York and Los Angeles' by James Lawrence, Burlington Magazine, February 1, 2013.