Chris Huen Sin Kan: Painting Again and Again

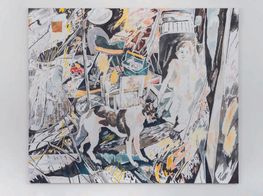

Chris Huen Sin Kan. Courtesy the artist.

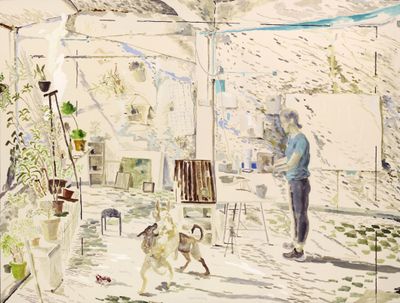

Chris Huen Sin Kan. Courtesy the artist.

Hong Kong artist Chris Huen Sin Kan hit the ground running upon graduating from the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 2013, where he obtained a BA in Fine Arts. In 2014, he staged his first solo exhibition at Hong Kong's Gallery EXIT, A Life in the Temporary (22 February–7 March 2014), which presented paintings exemplifying the 'existential gaze' that forms a core concern in Huen's practice.

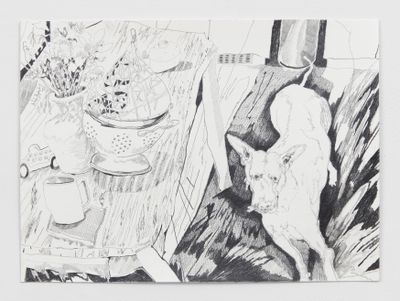

Huen does not sketch or plan his works before he begins to execute them on canvas, which all depict experiences that he renders as fully as possible in a style he describes as 'en plein air — hereto indoor'. Settings and subjects are familiar and consistent. His dogs, wife, and children appear in views of the artist's studio and home: unassuming, quotidian scenes rendered in quick strokes and watery swathes of earthy shades that balance the roughness of a sketch—and the measured presence of a Chinese ink painting—with the compositional weight of oil on canvas. In Doodood and John (2013), Doodood the dog lies next to a potted plant, ears pricked and eyes forward, as if responding to a noise that was just made. He appears again in Doodood, Mui Mui and Haze (2014), playing with Mui Mui the dog in Huen's potted plant-filled studio, as the artist's wife, Haze, looks on.

Huen's Gallery EXIT show was followed by another solo at the gallery titled Out of The Ordinary (17 July–5 September 2015), which was billed as an extension to the interrogation of the gaze that the artist showcased the year before. In Swimming (2015), Doodood and Mui Mui peer over the surface of a bed covered in a sea-blue sheet—the scene painted in such a way that the viewer becomes the person they are imploring to act; while in 8:30 AM, Getting Ready for Breakfast (2015), the artist, his wife, and Mui Mui lounge on a pointillist green bed that could pass for a field, their figures dwarfed by the details of the room that take over the scene. A billowing curtain appears like negative space save for the light streaks that mark its movement, while a fan to the side of the scene emerges from the leaf-like strokes that mark out a wall.

Even in these early shows, Huen's distinctive visual language is confident and fully formed. Oil paint, heavily diluted with turpentine, behaves like ink on paper—every fluid fleck and vital flicker recalling the rhythm of Morse code and the smoothness of the calligraphic line, building a paean to the sheer fullness of still moments.

Huen's later solo exhibitions include Re-Fresh: Chris Huen Sin Kan at Pilar Corrias in London in 2016, which was followed by another exhibition at the gallery, Of Humdrum Moments, in 2017. In 2018, the artist presented his first solo exhibition in the United States with Simon Lee Gallery in New York, and in 2019 he staged The Illuminated Mundane with Ota Fine Arts in Tokyo, returning to Gallery EXIT that year to present Tall Trees - and the things I might have forgotten. Throughout the years, the artist's subjects have remained constant, save for an addition to the family here and there, with the spatial settings having shifted from his grandfather's former home in Kowloon to a studio in Yuen Long.

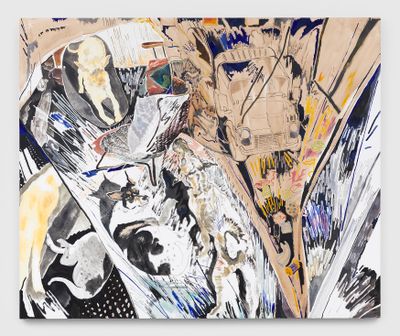

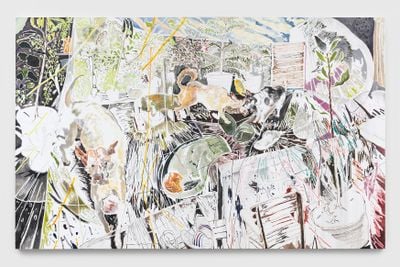

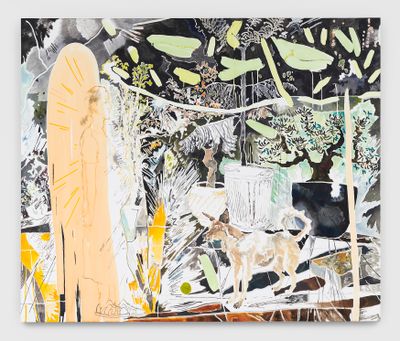

His compositions, however, have evolved with delicate shifts. In his 2018 solo with Simon Lee Gallery in New York, for instance, the instability of perspective becomes sharper in works where foreground, background, and figure are compressed in an image plane composed of multiple plateaus that seem to turn details into unruly patterns. In Haze (2018), Huen's wife stands amid swirling green leaves and slim, serpentine peach and ochre trunks, her form a uniform tawny wash that at once stands out and blends in.

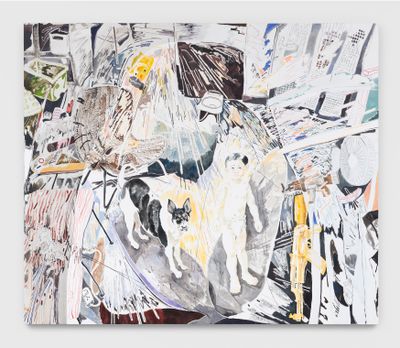

Puzzled Daydreams, the artist's latest solo exhibition with Simon Lee Gallery, inaugurates the gallery's online viewing space (3 April–2 May 2020). The show, which presents new paintings and works on paper, anchors the artist's relationship to the capturing of moments that he refuses to define as memories in the concept of the specious present, first proposed by E.R. Clay to describe the fact that the instance of 'now' is in fact a measure of moments.

In this conversation, the artist elaborates on his interpretation of this concept, and how it relates to his practice overall.

SBWhen did you realise that you wanted to become an artist?

CHSKI've wanted to work as a creative person ever since I was around six years old. Growing up in the 1990s in Hong Kong, where our pop culture was heavily influenced by the Japanese, the idea of working as an artist was limited, so instead I dreamt of becoming a commercial anime artist. Copying comic book characters was my very first experience making art and pursuing perfection. When I was around ten, I was lucky enough to travel around Europe with my family and I saw some paintings from the Renaissance period. It was a whole new world in comparison to what I did with just copying simple line characters. From there, I set my mind to learning more about art in every aspect.

My practice has reached an interesting stage where I'm using both Western and Chinese systems of painting, but at the same time am trying to cancel out both of them

SBI understand you dabbled in installation art as a student at the Chinese University in Hong Kong before turning to painting. How did you know that painting was your medium?

CHSKContinuing from your first question, the reason why I wanted to study art at college was all because I found a book named 100 Contemporary Artists A-Z in my secondary school library. Up until then, I had been reading art from the 19th century—I was surprised that art could be presented in different ways, and I thought the only way I could explore more was at college. For the longest period I thought I was going to make the trendiest art form, and then the struggle came in my third year, when I had to decide on my graduation project. I thought my project had to be the start of my life-long investigation on a subject, yet I didn't feel any personal connection to installation or media art. So, it was quite natural for me to turn back to what inspired me in my tender years.

SBYou have talked about how the differences between Western painting, which 'reconstructs things we've seen on a surface', and Chinese painting, which 'reconnects strokes to things we've seen', prompted you to think 'about what painting as a subject really means.' How has your practice enabled you to consider that question?

CHSKMy practice has reached an interesting stage where I'm using both Western and Chinese systems of painting, but at the same time am trying to cancel out both of them—kind of like putting both ideas in my mind to remind myself that neither of them are absolute.

Sometimes I decide my works are complete when I think all the information in the picture is consistent. Other times, I will consider my works to be complete when no more information can be added.

SBYour approach to painting speaks to these two systems. There is something very intuitive and direct in your process, with the moments you capture transferred to large-format canvases without prior sketches or drawings, recalling automatic writing or the presence of the calligraphic line, so as to express what you have called the 'pivot' of your art—the 'experience of gazing, subjectively complete though objectively fragmentary.' Were there any key influences that contributed to the development of this approach?

CHSKFor some time, I was particularly interested in existentialism and the idea that we all try to make rational decisions, despite existing in an irrational universe. It makes me think that we are always trying to rationalise what appears in front of us, though what we are seeing doesn't really have any absolute meaning. For example, I had a special experience when I practiced Chinese calligraphy. I was so focused on the form of a single Chinese character that it became very unfamiliar to me. I've never had that experience when reading a book or an advertisement. It makes me wonder whether a combination of strokes only means something when we come to a consensus. When I gaze at them separately, however, the strokes don't really mean anything at all. When I apply this to my surroundings, I realise we actually subjectively make up a complete version of what we see, but objectively the chaos remains.

SBYou start a painting with a few brush strokes and a rough idea of what you want to convey, which catalyses a cycle of reviewing and adding. Could you elaborate on this cycle of mark-making and evaluation that goes into each painting? How long does it take to complete a work, and how do you know when a painting is complete?

CHSKMy works depict the process of my understanding of a scene. When we are in a space, we receive information from our senses gradually; we are processing different sources of information, turning those that are consistent into a version of reality. When I'm working on my pictures, I'm constantly finding visual representations of sound, temperature, touch, and other experiences. Sometimes I decide my works are complete when I think all the information in the picture is consistent. Other times, I will consider my works to be complete when no more information can be added. Most of the time, I work on several paintings at once, allowing time and space to escape from being overly concentrated on a single picture, as what I want to depict is the experience of witnessing an accumulation of scenes from daily life, rather than specific moments.

SBAs you said, your paintings are not only a representation of moments but a perception and understanding of them. Your current exhibition, Puzzled Daydreams, pins this conceptual framework to the 'specious present', in which the experience of 'now' is considered an accumulation of seconds that are in fact a collection of 'pasts'—an idea that seems to build on solo exhibitions you have staged in the past. Could you elaborate on your understanding of the specious present?

CHSKThe scenery I depict hasn't truly happened in real life, but the subject matter—my dogs and my family, for example—does exist. I think of my works as records of what has happened in the physical world in which we all live. In a similar sense, a recorded song doesn't represent the resonance of instruments that have been played, but the encounter of the moment when it is played. I also want my works to show a present that is replayed when they are seen by someone or even myself.

I would consider my works as depicting a specious present that is paused at a reference point and replayed whenever it is being observed.

The idea of the present is interesting and complicated when it corresponds to our idea of time, space, and gravity. Sometimes I think the present is the point when time stops, like a pause in the middle of a video. But in reality, time can't just stop unless at an event horizon. Physically, we can't experience time stopping unless we are trapped in a black hole. For that reason, I would consider my works as depicting a specious present that is paused at a reference point and replayed whenever it is being observed.

SBAn enduring sense of presence is also articulated in the continuity of your subjects—notably, your wife Haze, two children, and dogs Balltsz, Mui Mui, and Doodood—and the settings in which you place them, which centre around your home and studio. Why do you focus so intently on such intimate subjects and settings?

CHSKIntimacy itself would be a short answer to that. But on top of that, I selectively depict the more uneventful moments in my daily family life. The less interesting and exciting moments tend to escape our attention. That feeling somehow resonates with the idea of stopping time in a poetic sense, I would say.

SBSpeaking of presence, how does it feel to be showing new paintings and works on paper online for your latest show?

CHSKAlthough I think my works are best viewed in person for a more complete and unconstructed experience, they can also be viewed as writings on my understanding of time and space, which can still be easily transferred through the internet. Viewers can see detailed, close-up images, which highlight some of the strokes and objects depicted in my paintings. It is also a unique experience that provides me with some new points of view when looking at works I am so familiar with.

SBYou have said that external changes of space affect your art. In that case, how has living in Yuen Long, which has been a flashpoint in Hong Kong's recent Anti-ELAB protest movement, influenced your work? More generally, does the context of Hong Kong matter when it comes to readings of your paintings?

CHSKIn the context of Anti-ELAB, I don't think it is just people living in Yuen Long who are affected. The protests have had a massive impact on the entire city. I don't intentionally put local political issues in my work, but I am looking back and trying to link different points. Sometimes I think my constant disappointment about the situation in my hometown is one of the reasons why I choose to depict unexciting moments of life. We are in fear of losing a high degree of autonomy, and it leaves a bit of bitterness, and my interests just don't gravitate towards excitement or happiness.

SBLooking at your paintings from 2013 to now, your subject matter remains consistent, but compositions become increasingly complex. Does this reflect the evolving density or intensity of your life experience?

CHSKThat could be one way to explain it. Being a painter, I also try to keep discovering how many different visual representations can connect the different occasions we experience in real life.

Undoubtedly, I think anime acts as one of the basic principles in my practice with regards to how lines, dots, and surfaces are read in a picture.

What I mean by 'different visual representations' is finding a new way to depict the same subject, which gives us different sensitivities under different circumstances. In my early works, I was mostly focused on the feeling and sense I spotted between different individual objects. The picture was made by linking up all the reference points within the painting. But in the more recent works I shift my focus on the sense I had when looking at the environment as a whole. That might be the reason why the compositions become more complex as emptiness has also became a thing in the picture.

SBIn your later work, I wonder if your background in anime comes through more, too...

CHSKUndoubtedly, I think anime acts as one of the basic principles in my practice with regards to how lines, dots, and surfaces are read in a picture. When I think about how to depict certain kinds of things, I must go back to a point where I'm trying to deconstruct and understand it.

On the subject of anime, I must mention one of my favourite comic series, which is Billy Bat by Naoki Urasawa. There is a scene with two comic artists who discuss how to draw a glass cup in front of them. One of the comic artists thinks drawing two circles horizontally and two straight lines connecting the edges of those two circles would be the best representation. The other artist asks him where this idea comes from. The whole scene suggests that when we want to draw something, we are actually copying other depictions that we once saw and understood in order to communicate with the viewer. A drawing doesn't show the subject itself, but a common understanding or experience when looking at the subject; much like René Magritte's idea behind the painting The Treachery of Images (1929).

SBYou have had quite a trajectory since staging your first solo exhibition with Gallery EXIT in 2014, one year after graduating from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Looking back, are there any particular paintings or exhibitions that are especially important when it comes to your growth?

CHSKI haven't reached that point yet. In the seven years I have worked as an artist, there have only been like one or two works I have felt fully satisfied with, and that number becomes zero when I feel too shameful to talk about them. I would say I'm still growing and trying to achieve the perfect representation of the idea in my mind. At this point, I would describe my practice as working on the same thing every time but making little amendments each time. In this regard, my first solo exhibition in 2014 was especially important because it marks the beginning of all the things I've done so far.

SBTo achieve the perfect representation of the idea in your mind—what do you imagine that would like?

CHSKThis is actually the hardest question for me. It is very hard to pinpoint a specific standard for a perfect work in my chaotic mind. Theoretically, I think the perfect representation of the idea in my mind would be the one that stops me making any new paintings again. In this sense, I will also need to admit that every work I have done so far is a failed attempt at pursuing this idea of perfection. But all these existing works also give me reasons and references to start over, again and again. —[O]