Clare Woods: ‘a lot of my work is about two extremes coming together’

Simon Lee Gallery | Sponsored Content

Clare Woods. Courtesy the artist and Simon Lee Gallery. Photo: Ben Westoby.

Clare Woods. Courtesy the artist and Simon Lee Gallery. Photo: Ben Westoby.

Doublethink at Simon Lee Gallery (6 September–5 October 2019), Clare Woods' first solo exhibition in London in ten years, marks a change in direction in the artist's practice. For over 20 years, Woods has expanded from her initial training as a sculptor at Bath College of Art—where she received her BA in 1994—to create abstract paintings on large sheets of aluminium. By painting these flat on the floor or on trestles, Woods has greater freedom of movement to push and sweep paint across the surface, allowing for the medium to be manipulated in a manner akin to sculpture.

At Simon Lee Gallery, new motifs include flowers and her first self-portrait, titled Ownlife (2019), rendered in pale hues against a dark blue background, with the artist's facial features depicted in sparse dabs of paint. Having started her career as a landscape painter, Woods gradually moved to painting objects such as rocks and sculptures, followed by the human figure in recent years; all the while maintaining her distinct style, which comprises broad strokes of paint hovering between abstraction and figuration. Interested in the connection between the landscape and national trauma, Woods' early influences include British landscape painters such as Paul Nash and Graham Sutherland. In recent paintings, vulnerability and mortality are expressed through the human form and flowers, such as It's the end of the World as we know it (2019), a large vase of peonies in the midst of shedding petals.

In this conversation, which is an edited transcript of a talk between the artist and Jennifer Higgie held at Simon Lee Gallery on 19 September 2019, Woods discusses the technical and conceptual shifts in her practice.

JHDoublethink at Simon Lee Gallery includes 14 paintings, all on aluminium, which were all pretty much done in the last five months. It's an incredibly complex, intricate, and accomplished body of work touching upon many things—some of them new for you. I'd like to start off with the title; why is the show called Doublethink?

CWI had been thinking about the show for a long time, and have been reading a lot of Orwell since the Brexit vote; it feels very contemporary of this moment. Doublethink is the idea of having contradictory views, and I think a lot of my work is about two extremes coming together and then meeting in the middle.

JHThe paintings are extremely vibrant; in some ways, they hover between abstraction and figuration, but they're also like short stories. They have very evocative titles, which often allude to songs, such as It's the end of the World as we know it (2019), Memory Hole (2019), and The Allnighter (2019). You also wrote the entries for each painting in the exhibition booklet. What is the role of narrative in the work?

CWTitles are really important, and in the exhibition booklet I wanted to give people another way into the work. I've collected titles for years—I might be driving along and see a name or hear something on the radio, or read something. When the paintings are finished and I stand them up, I usually know straight away what the title will be, but I have no idea until that point.

JHTo what extent is the finished painting dictated to by its title?

CWNone of the paintings are dictated by their titles, they always come at the end. The whole process is quite broken down, and the titling is one part of that.

JHWe'll talk about the conceptual side of these pictures later, but how do you physically make them? Do they begin with drawings?

CWAll of the paintings are based on photographs. Without photography my work doesn't exist, so it's really important. Thousands and thousands of photographs are collected, which I select quite instinctively and draw, taking out everything that I don't need to just leave a very slight trace. There are a few lines holding the image together, and that's the image that then gets drawn onto the aluminium panels. I paint flat, so the painting is horizontal and that control is really important. When you're painting while standing up, you've got this very small area of control, whereas when I'm walking around the painting, I've got much more control of the movement and pressure of the brush. I studied sculpture, so when I'm making these I think of them as objects.

JHWhen you do this, you're working very close up from an aerial perspective, so what you see is very different to what you worked on, in a sense. That must be quite exciting.

CWYes, when I'm painting, all I'm really thinking about is colour and movement, and the movement of the brush and the weight of the brush against the surface. They're all on white gesso, so as you push colour onto the surface, light comes through, so you can get different colours through weight rather than pigment.

JHWhat does painting add to a photograph?

CWI think it's about having something that's grounded in reality—that I recognise and can relate to on whatever level, then unpick and rebuild. It does feel very much like making sculpture, but it's flat.

JHWe live in a photographic world: we're constantly looking at photographs in newspapers, on Instagram, and so on. In a sense you're slowing vision right down and making yourself look at one photograph for a very long time, which is not something that many of us do.

CWBefore the internet, I'd go to friends' houses and ask to look at their photo albums; it didn't matter who was in the photographs, I just loved looking at them. Instagram has been amazing—I can trawl through thousands of photographs; but when painting, it's about pausing and stopping and trying to slow that process of looking down, even just for a few seconds.

JHYou have pictures of very varying scales and sizes in the show; what determines the size of the picture you make?

CWIt's incidental; it's about finding a source photograph and knowing I want to paint it. Sometimes I instantly know how it's going to work, other times I have to work things out.

JHYou're influenced by a lot of very well-known photographers, including Peter Hujar and Man Ray. What is it about those particular artists that attracts you?

CWI collect photographs and I have done for years. It used to be newspapers and magazines and now it's print-outs from the internet—they all feel the same, it doesn't matter the source of the photograph or what the photograph is of. I'm really interested in Man Ray because of his cropping, and I think that's always been quite an important part of my process, I've never really used a whole image. Annoying Ben (2019) is a painting of an arm and an elbow. The original photograph Man Ray took is of the whole person, and then he's got these white chalk pencil marks of where he wanted to crop, which changes the meaning of the image dramatically. The painting at the far end of the gallery, Tea Fixer (2019), is cropped at the knees—again, that was a very old photograph that I found, and there's no head in the photograph, and I think the cropping of it was what drew me to it.

The paintings are made in a very broken-down fashion. It involves dealing with a photograph, followed by drawing, then making the painting. The process of painting is quick, but it's very slow getting to that point.

JHYou paint in oils, and oils are famously slow to dry, but you mix them with resin, which is quick to harden. Essentially you're using oils like acrylics.

CWI'm dealing with oil paint in the same way I'm dealing with plaster or another material. I don't intricately mix all the colours separately, I might just have four or five colours, and all of the tonal mixing happens on the painting. I paint them in one hit, because they need to be painted wet so I can mix.

JHAnd what is it about the resin?

CWIt just makes the paint move. I've painted with enamel gloss for a long time, and in 2011 when I did the show at The Hepworth, I made these huge paintings and at the end I felt I couldn't do anything else with enamel. Adding the resin to the oil makes the oil physically act like the enamel gloss but with a much more complex range of tone.

JHYou started out as a sculptor, so it's almost like you still have that yearn to manipulate materials.

CWIt's almost the denial of being a painter, because I wasn't ever formally trained. I've kind of taught myself to use oil and to make paintings, but I've been doing it for a long time now.

JHOwnlife (2019) is your first ever self-portrait, which is really interesting to think about. You have painted other bodies and explored ideas around mortality—especially with the flowers—but you also often allude to injury, as in Memory Hole (2019), which is your daughter's mouth after she's lost some teeth; and The Cook (2019), which is a friend's bandaged hand. You've explored vulnerability before, but not through using your own body. What was it that inspired you to move into painting yourself?

CWIt was through a conversation with Anouchka Grose, who wrote the catalogue essay for my show at Dundee Contemporary Arts three years ago, that I realised that there's no connection between the source images that I work with. Instead, they're all connected to me. After that realisation, I allowed myself to be more instinctive and less prescribed about the way I use source material. It's almost as if I was trying to justify it. Alongside being in therapy, I'm now able to look at myself for the first time in a long time; I never wanted to paint myself before. Also, the photograph that I worked on for this was very slight; I wanted to try and paint a face using very few brush marks. When you look at it very closely, there's not much in that painting.

JHIt's true, you can see the face much more clearly when you're standing at a great distance from it, or even when you look at it reproduced in the book. When you look at it closely, there are all these floating elements.

CWIn a way, that is my experience of painting, because I paint really close to the surface, and it's only at the end when I stand back that I can see what's really there.

JHWould you say that all of the other work in this exhibition is a form of self-portrait even if it's not you specifically?

CWYes, because everything has an instinctive emotional response. Some of the photographs are found sources, and some of them I've taken.

JHWhen you walk into the gallery of your show, you're greeted with an amazing juxtaposition of images: huge, overblown flowers that are about to die, and a gaping, wounded mouth, which really sets the tone for the exhibition. It's very seductive, but it's also unnerving, in a way. Could you talk about the evolution of the flower paintings?

CWThe first time I ever painted flowers was two years ago, and it was from a photograph that I had taken—probably four years ago—in Venice during the biennale in a beautiful palazzo, which was really crumbly and sort of static in time. Life was carrying on outside on the Grand Canal, and then inside it was quite morbid—you know how Venice feels; it feels very fragile, although it's so grand. There was this big vase of dying peonies that I photographed, and I kept coming back to that photograph, but I thought, 'I can't paint flowers!' And then I just painted them, and it opened up a whole new way of thinking.

When I was thinking about this show, I was very much wanting to look at genres of still life and landscape and portraiture. The flowers felt very visceral, very internal, and they've informed quite a lot of the other paintings. Without the flower paintings, I couldn't have made that tree painting, for example, because I don't work on the paintings at the same time—one painting informs the next. It's very linear.

JHWhy did you feel initially that you couldn't paint flowers?

CWI don't know; it just felt so wrong. I questioned the need to paint still life. It was almost a rejection of the act of making a painting that someone's going to really like.

JHSo you wanted to push against the beauty, but you've also made quite beautiful paintings! I'm always particularly interested in still life painted by women, because for centuries when women weren't allowed to study from life and couldn't do apprenticeships, they'd turn to themselves or paint flowers, because that's what they had access to. Often in the history of still life and in flower painting, you see the most grief-stricken flowers. They can embody a huge amount—they're beautiful but of course they're also objects that are in the midst of dying.

CWThe only time I ever received a large number of flowers was when I was almost dying. Getting flowers when you're so ill; I struggled with it, but I knew I really wanted to paint them.

JHDo you paint them from photographs as well?

CWYes. The flowers as you come in through the door, those were painted from a photograph of some flowers at the end of our staircase at home.

JHAnd if they're flowers that are in your house, why not simply take a photograph of them rather than just paint them from life?

CWIt's always about flattening the object and turning it into a drawing, then taking everything away so it's just a few lines. I used to paint landscapes, and then I started painting other things such as rocks, then sculpture, and then I moved onto heads. I prefer working from black and white photographs, as it gives me the space to project my own colours onto the image. Photography also allows me to capture certain forms. In the case of the flowers, the petals were dropping, and I just needed to capture that moment.

JHDo you have a favourite flower?

CWPeonies! Followed by dahlias.

JHAluminium is an unusual surface to paint on; what's that about?

CWLots of reasons, really. When I work in the studio, I can't have anyone else in the studio so I'm dragging these things around and it's much easier to drag something solid. I use masking tape, which I cut to make areas that are masked off, which obviously wouldn't work on a canvas. I like the freedom of movement and the way the brush can move really quickly on a smooth surface. Also, I don't like that bounce—the answering back—that happens when you paint on a canvas, even if it's stretched really tight.

JHHave you painted on aluminium for a long time?

CWI used to paint on wood, but I've been painting on aluminium for 20 years.

JHI love the way you zoom in and become almost obsessed with certain subjects, which you rework again and again, as if you are seeking some kind of endpoint. The tree depicted in The Upsidedown (2019), that one has a special story . . .

CWYes, it's a tree that I've been photographing for years in Austria. It's on the side of this mountain and it's the only visible tree; it's really odd. It's sort of hanging on for dear life and every year a bit more has broken off or it looks a bit battered. I became somewhat obsessed with its angle on the slope and wanted to paint it. I've painted it twice, and I don't tend to repaint anything because once I've painted an image, that tends to inform the next one.

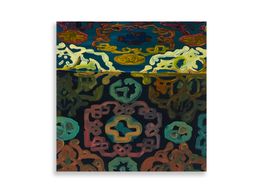

JHYou mentioned that being in therapy has opened up certain aspects of your practice that you were not exploring before. Consciously Contemplate (2019), which is in the downstairs gallery, alludes to therapy. It's a painting of a kneeling figure on a rug that makes you think of Sigmund Freud.

CWYes, the idea of being incredibly naked and vulnerable when you're in that position. It was painted from a black and white image; I've had it for about 25 years, I don't know its source.

JHWas she kneeling in a psychiatrist's study?

CWNo, that was just how I felt about it. I also chose it formally because I wanted to try and bring the background and the foreground together a bit more.

JHI recently gave a talk at the Freud Museum in Hampstead with some artists whose work was in an exhibition there. Often, with any kind of creativity, you're trying to struggle with something while you are working something out. The artists had been in therapy and were saying there's always this slight worry that if you're in therapy you might become so well that you don't want to be an artist anymore. Do you ever worry about that?

CWI did at the beginning, but I was so ill that if I hadn't done anything about it, I wouldn't be here. It really helped, and it hasn't hindered my creativity because it's allowed me to deal with a lot of other things that were holding me back, so it's been good.

JHDo you see this body of work as an ongoing conversation?

CWIt's always an ongoing conversation, but it's also very linear. It's like making an album, I guess; they've all got to work together and enhance each other. There is not one painting that sums up the whole practice, it's how they relate to each other. They've also got to exist in their own right when the show is over.

JHWho would you say are your main artistic influences?

CWI get asked that a lot, and I go through phases of having these sort of love affairs and reading everything about certain artists, but they're mostly sculptors. At the moment it's Eva Hesse, whose sculptures are quite big whereas the paintings are quite small. I saw the paintings for the first time a couple years ago at Hauser & Wirth and I couldn't put the two together, I was trying to understand how they relate to each other. They feel very separate.

JHWhat about when your practice was evolving? Who were your influences then?

CWVery early on I looked to modern British artists such as Paul Nash, along with other painters who were looking at the landscape in times of trauma, after the First and Second World Wars, for example. I was at Goldsmith's in 1999, when being a female painter painting landscape was a little bit out on a limb and very uncool. I remember absolutely loving John Currin and Cecily Brown, who were a generation above me, along with Gary Hume.

I spent a long time trying to work out why I was painting landscape, and that's when I really started thinking about the connection between the landscape and national trauma. I'm quite interested to see whether what is happening now politically will influence painting. We see a lot more figurative painting now.

JHFor a long time you were painting these quite monumental landscapes, and a lot of them were based on the Welsh Border; what was it about that particular landscape?

CWWhen I was living in London, I started following the Leominster Morris dancers, who dance in the landscape in response to what has happened there historically. I used to go off on the weekends and follow them and take photographs of the landscapes they were dancing in. The England—Wales border is quite interesting historically and there are not many people living there.

I didn't feel comfortable living in East London in the early nineties; I never felt comfortable coming out of my studio at night and I hated feeling like that all the time. And then we moved to the middle of nowhere and I found that really scary as well, so I realised it's not where I am that's making me feel this way, it's me.

JHAnd how did that landscape in the middle of nowhere affect your painting?

CWIt became part of the everyday, so eventually I couldn't see it anymore. And that's when my practice started to change. Alongside the landscape paintings, I always collected photographs of rocks and other natural objects, and it was at that point when I was working on The Hepworth Wakefield show and I started photographing these rock forms, which led me to painting sculpture, followed by heads and figures. It came from painting the landscape.

JHI visited your studio in Hereford four years ago, and you showed me some quite disturbing photographs from the First World War of bandaged soldiers juxtaposed with photographs of ballerinas. I thought that was really fascinating, because although ballet is extremely beautiful, the feet of ballerinas are often bleeding and broken and bruised. It's the same with landscape, I guess; they're often beautiful but have dreadfully dark secrets—they might be where a battle has taken place or where people have been oppressed for being peasants. I think there's a very strong element of your work that pushes and pulls against this ostensibly beautiful image that actually has a very dark heart.

CWThat's good; that's what we're aiming for!

JHWhat do you think you'll be focusing on, moving forward?

CWSelf-portraits and still life at the moment, and working on smaller paintings. I find working in large-scale much easier. Painting small is really hard, because your movement is limited, whereas big paintings allow me to really move and press and be quite rough. —[O]

—