Daniel Boyd on Decentralising Perception

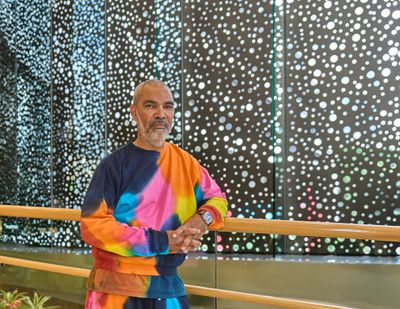

Daniel Boyd with Doan (2024), Pacific Place, Hong Kong. Courtesy Pacific Place.

Daniel Boyd with Doan (2024), Pacific Place, Hong Kong. Courtesy Pacific Place.

Daniel Boyd, one of Australia's most acclaimed artists, spoke with Diana d'Arenberg in Hong Kong on his new installation Doan for Art Basel's Encounters.

For hundreds of years, Indigenous histories in Australia were depicted through a colonial lens, which celebrated British colonisers as explorers and relegated Indigenous stories and experiences to the sidelines.

First Nations artist Daniel Boyd holds up a different perspective, working to dismantle and reinterpret the foundational myths and narratives that have dominated Australian history. Boyd sets about reframing the narrative of Australia's Indigenous peoples, examining the construction of history as a product of a time and place, tied to colonial ideologies of expansion, empire, and nation building.

Born in Cairns in 1982, the Sydney-based artist studied at the Australian National University's School of Art and Design in Canberra. Of Kudjala, Gangalu, Wangerriburra, Wakka Wakka, Gubbi Gubbi, Kuku Yalanji, Bundjalung, and ni-Vanuatu heritage, Boyd has described how his great-great-grandfather was kidnapped from Pentecost Island in Vanuatu and enslaved on Queensland's sugar-cane fields. His grandparents were part of Australia's Stolen Generations, in which First Nations children were forcibly removed from their families as part of the government's policy of assimilation from 1910 to the 1970s.

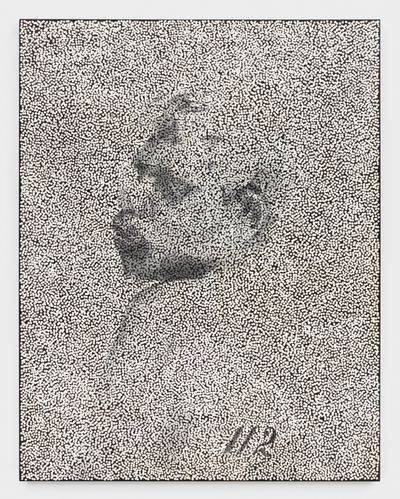

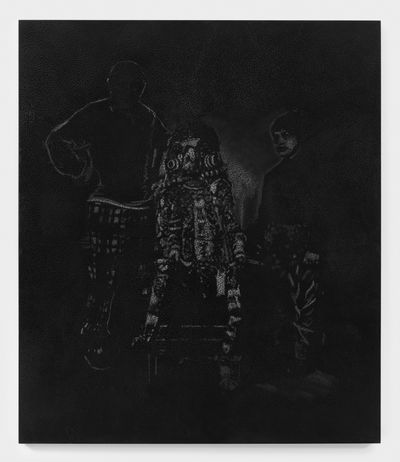

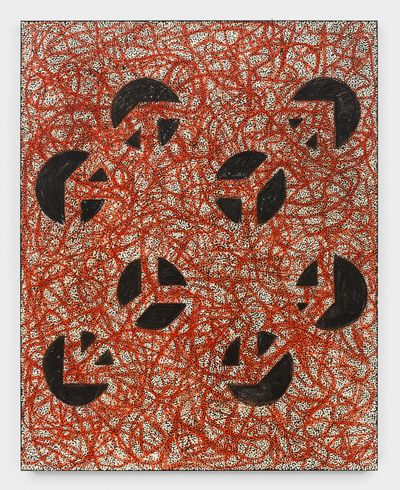

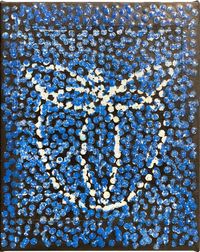

This history makes its way into Boyd's work through the use of personal photographs, memories, archival imagery, and historic portraits as sources for his paintings, which are covered with translucent, reflective dots of archival glue. The use of these dots, or 'lenses', as Boyd refers to them, is a signature of his work and employed across installations, moving images, and paintings. 'For me the circle acts as a lens, so it's about perception and multiple entry points into specific ideas of things that I wanted to work through', Boyd explains.

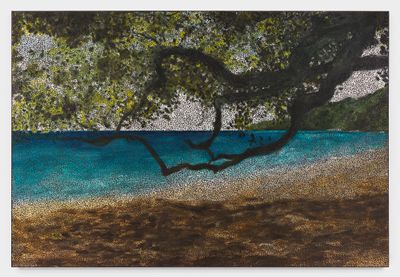

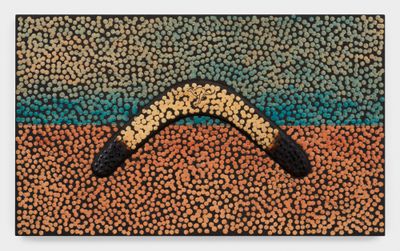

The stippled application of the glue over the painted surface creates a heavily pixelated effect, which works to obfuscate or distort the underlying image. Figures appear on the water as though seen through a thick fog in the black-and-white painting, Untitled (SCAMSCI) (2018). In Untitled (2012), a dark landscape with a strip of blue water in the foreground appears hazy, as if our eyes are shrouded in gauze.

Disrupting the power of representation suggests the complexity of the human experience. Symbolic of the nature of memory and its gradual degradation, Boyd's lens paintings examine how information and knowledge is lost over time. Each image is both incomplete—much like the recording and telling of history itself—and mutable, adjusting with shifts in light to result in a different experience for each viewer. The lenses disrupt the painting but also allow for a multiplicity of narratives and histories, an idea that is central to Boyd's practice.

Currently on show in Pacific Place mall in central Hong Kong is Boyd's three-part site-specific installation, Doan (2024) (21 March–7 April 2024), presented by Kukje Gallery (Seoul/Busan) and STATION (Melbourne/Sydney) as part of Art Basel Hong Kong's 'Encounters' offsite programme curated by Alexie Glass-Kantor.

Doan is composed of a newly created moving-image work, a mirrored stage floor, and, on an upper level of the mall, a window treatment. At the preview, Boyd described the three synergistic elements as 'speaking to the same language': the works expand on his visual language and use of repetitive lenses, and are in dialogue with one another.

Not for the trypophobic, the wraparound black window treatment is perforated with the artist's signature holes, playing on the movement of light throughout the day. Seen from outside at night, as the mall lights glow through the perforated window, the work resembles a constellation set against Hong Kong's urban concrete jungle.

The moving-image installation, which runs on an 11 minute loop, is similarly composed of a layer of static holes that act as a filter for the assemblage of technicolour moving images underneath, appearing as a hypnotic moving painting. The static is in dialogue with movement, and darkness plays with light as colours from the screen are reflected in the mirrored floor work, a black platform covered in reflective silver lenses. These lenses both fragment and reveal the surrounding architecture, speaking to the layered histories of the spaces and constructing non-linear relationships between different geographies and time scales.

Doan is ever-changing, responding to its surroundings and to fluctuations in light throughout the day. It draws in passers-by with its shimmering, reflective surface and colourful moving images, and encourages them to engage in a way of looking that transcends the physical medium.

The following conversation merges two discussions between d'Arenberg and Boyd that took place in 2022 and 2024, and has been edited for length and clarity.

DDYour practice involves reframing and questioning history, particularly the British colonial narrative, highlighting how art has been used as a tool to reinforce these narratives and frame our historical knowledge. Is your focus on the power of art to reframe history something you developed as you were confronted with colonial portraits in museums?

DBWhen I went to university I became interested in the language of power that was implicit in representation in 18th- and 19th-century English portraiture. In a portrait of James Cook by John Webber [Portrait of Captain James Cook RN, 1782] there was a particular narrative that had been played out in this country [Australia]. I wanted to understand who I was as a person in relation to a representation of [Cook]. It was a fraught process of trying to represent history—it's not linear. There's a lot of complexity within that.

When you have images, artworks, paintings in particular—I was studying painting—and you don't relate to a specific narrative, you don't feel like it represents you as a person, how can you connect to that artwork?

What I try to do is create an open space that audiences can activate. I wanted to think about the idea of plurality or multiplicity, trying to give equity to different ways of seeing. In introducing multiple lenses to the painting surface I'm trying to decentralise perception so there's no singular way into the work, there's not a proposed way of seeing it. There are multiple connection points.

. . . it's about experiencing the work through life, so that it's not static, it's in constant motion.

I'm trying to create movement in the surface of the works so that audiences activate the work and in turn become complicit in the action of seeing. As we move through time and space, we're continually gaining associations; we're not static. We're constantly evolving. So that's a part of how the viewer engages with the work.

I wanted viewers to have this real experience, but also to understand how they engage with something that might hang on a wall. It's about making the experience of connection to the art or arts more tangible; it's about experiencing the work through life, so that it's not static, it's in constant motion.

DDWhat is the significance of the lens motif for you, and how does the process behind these works communicate the message you're trying to convey?

DBIt's a combination of things, but it is about using light to create movement on the surface so that audiences can activate it and feel a different type of connection to the work.

For me, the relationship to darkness, or doan, is about light as well.

It's basically about how people connect to the work. But it's also about creating a situation through different interventions where you have to acknowledge what's not there, and it's about making what's not there present—to represent history or to negate something in history, you have to have the two together.

So it's about making art in a way so that you understand it's not what you see in the first instance, and creating a framework to allow people to see things in relation to the other. It's also about the human experience of the abyss—of being inside and outside the abyss. I think this is what I do with my paintings.

DDYour personal history and that of your family is inextricably linked to the issues you address in your work—the personal is political. Can you talk a little about your personal history and how that shapes the kind of art you make?

DBI do create works within a particular context. Works that appeared in a group show at Château Shatto in Los Angeles titled The History of Forgetting in 2022, such as a painting of Muhammad Ali at the Aboriginal Legal Service in Redfern [Untitled (AALS), 2022], speak of the relationship between the community and the civil rights movement here in Sydney, and the civil rights movement in the U.S.

I think the personal allows me to ground my expression in lived experience, so that it's not detached in any way from me and the work that I make. I can still speak about bigger things by representing that lived experience. It is about inheritance.

DDA lot of your work engages with issues of Country, memory, and trauma, and these are connected to conditions of legacy and survival.

DBThe act of making for me is a continuation of that. I am my mother and father's child. It doesn't matter where you come from, or what culture you have a relationship to—you are creating work as a human being. It creates a kind of pause to understand how each person relates to others. Understanding the continuation to lineage. My work is about connecting to the past.

DDTell me a little about the work Doan and the story behind it?

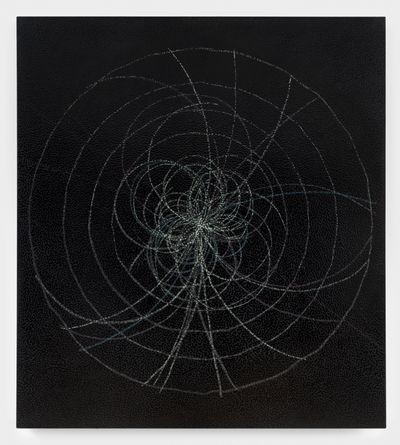

DBDoan means darkness in the Yugambeh language, which is from the southeastern region of Queensland. Again, the circle acts as a lens, so this element is about perception and offers multiple entry points into specific ideas that I wanted to work through. This framework connects to the unknown or the unconscious, or what we can't comprehend about our relationship as humans to others, to the places we inhabit, and our relationship to the universe. So this acknowledgment of the unknown speaks to this space of darkness.

Right now, the importance of locality, of not losing the traditions that make difference, is globally relevant.

If we understand each circle or each oculi as a way into something, then for me it gives a sense of equity on how we engage in ideas. It's about dispersing these ideas into an exchange that is offered to different people from different demographics, different age groups. For me, the relationship to darkness, or doan, is about light as well. Light is very important in the work—it's something that has driven this understanding of the consciousness, as well as what we don't understand.

DDI want to talk about this idea of opacity—a concept espoused by Édouard Glissant, whose writings you have talked about—that underlines your work and manifests itself through your visual language, through the use of the numerous lenses that obfuscate the underlying image in your paintings. This idea of a 'right to opacity' of marginalised people, as opposed to the ideal of transparent universality imposed by the West. The idea of opacity as an anti-colonial force and resistance, and as the right for difference. What is the importance of this in your practice?

DBI came into contact with Glissant through Okwui Enwezor after the [2015] Venice Biennale5. He and his peers had an engagement with Glissant and his philosophy, and he saw my language and what I was doing in my own context, thinking about these things. It was nice to have a parallel way to express some of the ideas that I work with.

Opacity was really key in expressing the integrity of someone's sense of self and not being subjugated or consumed in a way that is detrimental to the way we understand ourselves as humans. So, being part of an exchange without losing sense of oneself; it's just how we as the oppressed have lived in the world. You have to hold on to those traditions or those forms of connection to others, or any form of relation or connection to tradition or transference. [Opacity] offered the language for that.

And right now, the importance of locality, of not losing the traditions that make difference, is globally relevant. That's what makes the world beautiful: that we are all different. Opacity tries to speak to that.

DDIn your paintings the idea of opacity comes through physically and literally, with the dots obscuring the image underneath so you don't get the whole picture at once. The mirrored floor work of Doan, however, feels different to the paintings in that the space, insofar as the environment and the people walking onto the floor are reflected in the work. The reflective circles contain visual information rather than obscure it. There's a play and relationship between opacity and the immediately visible or transparent in these new works.

DBI guess that working spatially is another way to connect with the aura. Historically, humans have tried thinking about the spirit or aura in particular ways, and a built environment offers a singularity. My proposition with the porosity of the space in which the works are situated is that the oculi disperses this sense of control. It's a way to situate the audience in the language and disperse the sense of self.

DDYour works require audience activation and engagement. How have the different spaces you've created installations for—Gropius Bau in Berlin, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia in Sydney, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander memorial at Australian War Memorial in Canberra, and now Pacific Place shopping mall in Hong Kong—impacted the way audiences engage with the works? Does the context in which the work is displayed change the way it is perceived by audiences?

DBYeah, these encounters are important in understanding how accessible art is to the public. People may not come from those traditions, those western understandings where the art canon is a part of who they are or how they understand themselves in relation to it. So, I feel there's a sense of accessibility and equity in how they engage with my work. They might find it intimidating to go into a museum or gallery, and these chance encounters in public spaces, it's a different audience for me. I really enjoy the opportunity to share my expression in a different way. —[O]