How Do Museums Remember?

Including works by Yuki Kihara, Oliver Laric, and the Guerrilla Girls among others, Oh, Museum at Cement Fondu in Sydney (22 May–11 July 2021) examines complex questions around representation and authenticity.

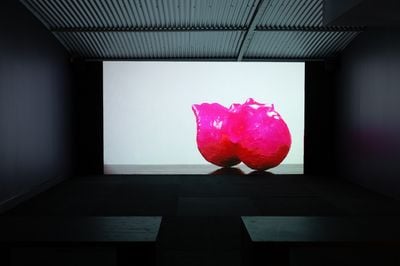

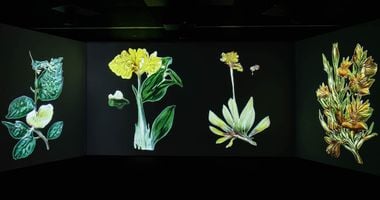

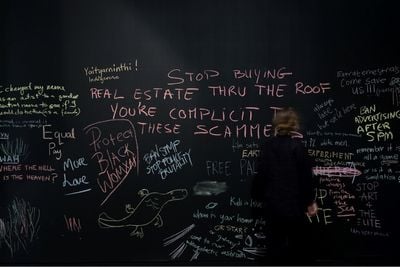

Exhibition view: Oh, Museum, Cement Fondu, Sydney (22 May–11 July 2021). Courtesy Cement Fondu.

Claiming to 'turn a spotlight on the somber grandiosity, assumed authority and monolithic narratives traditionally upheld by Western museums and art institutions,' the exhibition exemplifies the debate around cultural preservation and the ways digitisation impacts the legitimation of knowledge distribution.

It's a contemplative space, theatrical in tonality with a melancholy vocabulary. Through a process of cultural mimesis and by re-staging ancient artefacts into synthetic imitations, works reconstitute the deployment of history and agency, and investigate the making of knowledge production in the process.

Iranian artist and activist Morehshin Allahyari's participatory installation reconsiders the analogous relation between ancient monuments and information: part of the artists' 'Material Speculation' series (2015–2016) featuring replicas of statues from the city of Hatra, which was located between the Roman and Parthian/Persian empires, and Assyrian artifacts from Nineveh that were destroyed in 2015 by Islamic State militants and dramatised on YouTube videos.

Allahyari's Unknown King of Hatra (2015), Gorgon (2016), and Maren (2015) are copies of ancient monuments reproduced in glossy 3D-printed resin, with a memory card and a flash drive storing documentation of maps and research material concealed inside.

Allahyari's work is an intelligent critique of information exchange and authorship. Through this process of re-staging, the artist displaces the original meaning and transfers a renewed agency to its synthetic imitation. This attempt for cultural redemption, however, invites a perplexing observation: if history is incongruous with the present and repeatedly modified and re-moulded, as witnessed here, which, and whose, version of history is this reproducing?

Aside from redefining the parameters of representation and originality, Allahyari's two adjacent ancient historical South Ivan Human Heads (2017) mounted with suspended USB cords, establish an unconventional tongue-in-cheek dialogue with Austrian artist Oliver Laric's Life Masks (2016) of Hollywood celebrities.

Referencing historic 'death masks' of deceased people, Laric's celebrity life masks were originally purchased from eBay and then remade in the form of electroform copper as reproducible mementos of contemporary icons.

Underpinning the implications of a mass-media cultivated society—here, the slippery exchange between Leonardo DiCaprio and ancient figures—complicates the sensitivity of what constitutes value in the making of cultural production today. If meaning is constructed from myths and historical truths, what criteria is employed to authenticate authenticity?

Oh, Museum embodies a powerful paradox. It presents a multi-layered critique of museological processes, institutional pedagogy and promotes regeneration while addressing the under-representation of Indigenous cultures.

The critical drawback, however, as observed in this show is that meaning and authenticity are often measured by returning to historical benchmarks—whether myth or truth—as a way of substantiating the present, so, it's a perpetual cycle.

Australian artist Jamie North investigates these recurrent twists and turns in Spoils (Hillsdale) No. 1 and No. 2 (2021). These entropic installations cultivate an internal botanical system, where plant life flourishes into new spatial configurations from the material of his existing artworks.

Embodying a dystopic tension between erosion and rebirth, North's works personify the cyclical entropy of time and postulate, evidently, the science of plant intelligence. The use of the term spolia (Latin for 'spoils'), also refers to the repurposing of built structures or ancient sculptures into new monuments.

Anchoring the exhibition is Sāmoan artist Yuki Kihara's video Invocation (2016). Informed by the Sāmoan traditional dance of the Taualuga, Kihara's hands form, through repetition, the image of a skull, recalling Salvador Dali's surrealist painting Ballerina in a Death's Head (1939). Appearing as a consecrated space, Kihara's film conveys an allegorical premise: a hand engaged in gesture.

Throughout Oh, Museum, there arises a question about cultural transfer and the stories we tell. If all human civilisations rely on a type of cultural book, that is, according to British classicist Eric A. Havelock, 'on a capacity to put information in storage in order to reuse it,'1 then who is collating these recollections into an archive of knowledge or total history?

Who is authenticating, measuring, and classifying, or rather, dismantling this information? And who determines what constitutes knowledge itself?

Australian artist James Tylor's tintype 'Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange' (CIPX) series, attempts to address these questions by visually resurrecting the representation of Indigenous cultures formerly depicted by European anthropologists during the 18th and 19th century. This time with leading Indigenous curators, arts workers, and artists, such as Coby Edgar (Larrakia & Jingili peoples), Tina Baum (Larrakia, Wardaman & Karajarri peoples), and Dean Cross (Worimi people).

Here, Tylor intensifies the efficacy of deconstructing a sense of historical permanence to re-claim a future history in what is a poetic resurrection: of the destruction of cultural memory reconfigured into new symbolic resonance.

In its engagement with the museum's role as an authenticating body of knowledge and the role of new technologies to either demystify or reclaim its narratives, Oh, Museum embodies a powerful paradox. It presents a multi-layered critique of museological processes, institutional pedagogy and promotes regeneration while addressing the under-representation of Indigenous cultures. But it also liberates the art museum of a certain accountability by illustrating that these unresolved issues are, effectively, precariously embedded in the ontological view surrounding authentication, authorship, and the colonisation of information and representation.

Take the Guerrilla Girls' Complaints Department installation, which disrupts the tone of the exhibition with a space to write complaints about art, culture, and politics on the gallery walls. Resembling a school classroom with chalk and a blackboard; perhaps a gesture leading back to academia and the genesis of knowledge distribution.

Whether through repetition, imitation, or mimesis, the performance of knowledge seems, more so, a reenactment of history in the present. —[O]

1 Eric A. Havelock, Preface to Plato, 1963, (pvii).