Hammad Nasar

Hammad Nasar. Courtesy National Pavilion UAE.

Hammad Nasar. Courtesy National Pavilion UAE.

I met Hammad Nasar at the fledgling Hong Kong International Art Fair in 2008 (four years later the fair had transformed into the slick Hong Kong Art Basel), manning the Green Cardamom booth, a gallery and arts organisation he and his partner Anita Dawood founded in 2004 with the aim that the art they sold would finance their non-commercial projects and exhibitions.

As I stood in there, I knew I was seeing something unusual: a curated show of some of the most interesting art I'd seen from the South Asia region.

At the time I was also struck by Nasar's incredible enthusiasm and knowledge for the pieces on the walls. And another quality distinguished Nasar from every other gallery owner in that space: there was no sales pitch.

As it turns out, Nasar was eminently better suited to the non-commercial, indeed the academic, world of contemporary Asian art. In 2012, Nasar and Dawood wound up Green Cardamom when they moved to Hong Kong so that Nasar could take on the role of Head of Research and Programmes at Asia Art Archive (AAA). He spent just over four years at the Archive, before moving back to London in 2016.

Nasar, like many in the art sphere, wears a number of hats: critic, researcher, curator, to name a few. He was appointed curator of the United Arab Emirates Pavilion for the 2017 Venice Biennale, and recently took up a research position with the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art (part of Yale University) in London.

He is also newly appointed Senior Research Fellow (Black Artists and Modernism) at University of the Arts London.

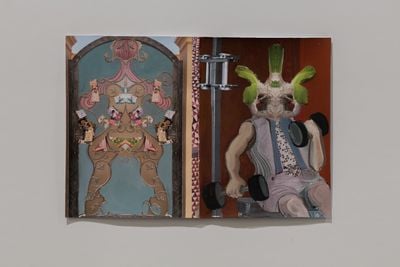

SAYou've had a busy 2017 so far, not least as curator of Rock, Paper, Scissors: Positions in Play, the UAE national pavilion for this year's Venice Biennale. Please tell us about the premise behind the exhibition.

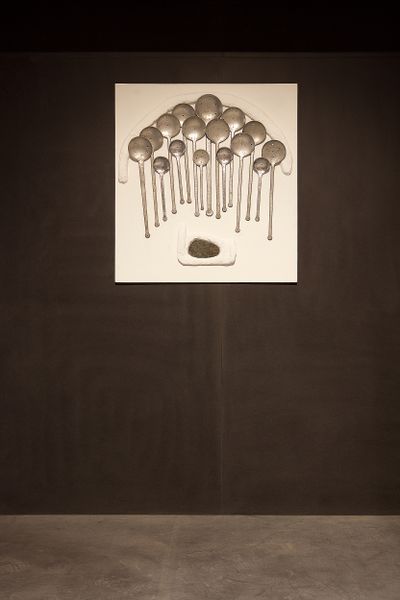

HNIn my observation of art in the UAE, I noted a set of diverse practices that shared an attitude of playfulness: collecting, repetition, the application of arbitrary rules, flights of fancy, record keeping through diaries and photographs, gestures based on experimentation and performance.

On being invited to curate the UAE's National Pavilion, I proposed an exhibition that would explore the analogy between 'playing' and artistic strategies that use 'play'.

Play is the means through which children first come across difference and learn to negotiate their own path as social beings. It is the vehicle through which they understand, internalise, but also push against rules.

This capacity for play to mediate and test possibilities is, I suspect, what gives it such valency in the Emirates, where conservative social norms, a growing and shape-shifting art ecology, and a unique set of demographics, make the sideways approach a more productive artistic proposition.

Where does this artistic impulse to play come from? Where do different forms of play take place? How are they nurtured? Who can play? And what does play do—in particular as part of the process of making a place home?

These questions felt compelling, and the pavilion became a platform to think about them in public, with the publication and programme serving as additional sites of play.

SAI understand one strand of the exhibition offers institutions such as Art Gallery at NYU Abu Dhabi and Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts, London, the opportunity to develop activities that sync their own programmes with the exhibition?

HNThe collaborative programme is an experiment coming out of a desire for the project to contribute to the UAE artistic community's collective conversation. Think of it as potluck—where different institutions will cook up something of their own making, for all to share. The ambition here is to catalyse, not direct. Let me share a couple of examples.

The Art Gallery at NYU Abu Dhabi's recent exhibition, But We Cannot See Them: Tracing a UAE Art Community, 1988-2008, took its title from a poem by Nujoom Alghanem, whose work can be seen in the UAE pavilion. For our collaborative programme, NYU Abu Dhabi hosted a series of events built around screenings of Alghanem's films.

Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts, London (CSM), now includes what used to be the independent Byam Shaw School of Art, where the influential UAE artist Hassan Sharif obtained his formal art education in the early 1980s.

Working with faculty members and two students at CSM, we are developing an event in October 2017 to explore the role of pedagogy and the art school in shaping practice.

SAThe Middle East is having a moment in the world of contemporary art. What level of audience awareness, globally, is there of art from the UAE? Do you think art such as that seen in Rock, Paper, Scissors challenges some of the perceptions the art viewing public might have, not only about the art, but about the cultural, social and political conditions of the region?

HNI suspect there is little global perception of 'contemporary art from the UAE', and rather than artistic practice, it is ideas of art infrastructure (museums, art fairs, biennales ...) and resources (budgets, prices ...) that occupy greater share of mind when the UAE comes up in conversations.

I see Venice as an opportunity to shift this focus to the diverse artistic practices being nurtured in the UAE. I cannot judge how people will perceive the project; I can only share my own perspectives.

'Home' and 'nation' are cultural constructs that cannot be restricted to passports and ethnicity. Home is the food we eat, the stories we share, the songs we sing and the games we play. In selecting works, I was interested in practices that explore belonging as acts of presence and imagination, by artists who call the UAE home, whatever their passports.

For the UAE, with a population where 85 percent are not citizens, there is an interesting challenge around how to negotiate the terms of 'belonging'. In this challenge is also an optimistic possibility of new forms of cosmopolitanism that have a different relationship than colonial or imperial models of the past.

SAYour exhibition Lines of Control: Partition as a Productive Space (2005-2013) found productive spaces in the no-man's borderland between Pakistan and India, and in part dealt with one of the biggest issues the world faces today: the 'refugee problem', the exodus of those fleeing war, particularly from Syria, and their movement across borders to find a new home (one that is not always welcoming).

It seems to me that your worldview is less about geographical barriers and the borders that spring up, and more about the human misunderstandings and misreadings that create these walls in the first instance. Can you talk about this idea?

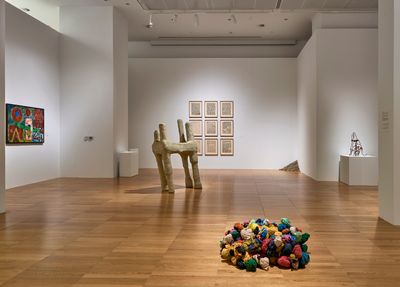

HNLines of Control: Partition as a Productive Space was not a single exhibition, but an accumulative platform that included workshops, projects, talks, a research fellowship, films screenings, symposia, a 240-page publication and multiple exhibitions of over 40 artists held across time, on three continents.

The project used the lens of contemporary art to explore the partition of British India (1947) into the nation-states of India and Pakistan, and (post–1971) Bangladesh. These two events (1947 and 1971) displaced an estimated 25 million people and resulted in the loss of over 3 million lives, but left a tiny mark on the world's collective visual memory.

Lines of Control was an attempt to explore this lacuna—not through the trauma of the events and their aftermath, but by engaging with partition's literal capacity to produce things: nations, borders, new histories and reconfigured memories.

How to live with our partitioned selves has never seemed a more urgent question for all of us.

By the time of Lines of Control's two largest iterations—at Cornell University's Herbert F. Johnson Museum (2012) and Duke University's Nasher Museum (2013)—the project had expanded its geographical focus beyond South Asia to include multiple and entangled histories: from the Indigenous peoples of North America to Ireland, the Koreas, Armenia, Israel, Palestine and the freshly formed nation of South Sudan.

And had morphed into a meditation on what it means to live together with difference—of race, ethnicity, class, wealth, language and belief.

These explorations of belonging through inhabitation are equally relevant to South Asia, the UAE, the UK, the US and the South China Sea. How to live with our partitioned selves has never seemed a more urgent question for all of us.

SAYour way of working as a curator seems to involve the founding and proving of an intellectual idea through the exhibition of art. In other words, a research-based project that could theoretically result in something else other that art being produced. Is this a fair summation?

HNFor me, making exhibitions is a way to think with artists and through art about questions that niggle—like pebbles in a shoe. Research is central to my curatorial projects, but not all research lends itself to exhibitions.

Papers, symposia, lectures and talks are also forms of output that scratch particular itches. I am, however, deeply attracted to projects that can support both exhibitions and publications.

As sites of discovery, encounter and possibility, they circulate in different ways and can become machines for collaboration.

SAAsia Art Archive was a groundbreaking institution in Asia when it was founded in 2000. There has been immense growth in Asia in all areas for art—but still much room for growth. How is the canon of contemporary Asian art history is being constructed in Asia (and outside of Asia) today?

HNArt and its histories, particularly outside Euro-America, are habitually framed in units of geography—the nation, the region (e.g. South or Southeast Asia) or the linguistic bloc (e.g. the 'Arab world' or 'Francophone Africa').

Art historical discourse in Asia faces significant structural obstacles of circulation: state control; multiplicity of languages; the lack of translation; and the absence of viable distribution networks.

How we do this is a work in progress, but a possible answer lies in an idea that I have been trying to articulate as 'art histories of excess'.

With the result that the most readily circulated art writing is often commissioned for gallery catalogues or large-scale international exhibitions; frames a suitably (usually economically) attractive nation or region; is written in English; and, aimed at a 'global' audience with some curiosity but scant prior knowledge.

These factors tend to make for rather 'thin' art histories, overly reliant on mechanisms of validation elsewhere; on being 'discovered' in retrospectives in New York or London; showcased in the 'Masters' or 'Modern' sections of art fairs; or being the subject of PhD theses supervised by a handful of scholars.

While adding more 'stops' (Hong Kong, Singapore, Sharjah ...) builds capacity, it doesn't fundamentally change structural features.

The need is not just to add more content to existing structures of knowledge and circuits of validation—but to expand our collective understanding of what this thing called art is, and make visible its entangled genealogies, its undisciplined present and its myriad futures.

For this we need to allow our existing structures of the academy, the museum, the archive and the market to be productively overwhelmed. To enable an exponential rise in the sheer quantum of artists, writers, languages, institutions and contexts that we could cope with as a field addressing Asia, however we define it.

How we do this is a work in progress, but a possible answer lies in an idea that I have been trying to articulate as 'art histories of excess'.

Dominant national narratives can flatten or erase significant differences.

These are art histories that exceed the 'lives of the artists' mode of history writing; that pay attention to circumstances, to pedagogy, to circulation, to patronage... even to bureaucracy.

Histories that take account of art's capacity to be multiple things at once—aesthetic form, economic commodity, political urgency, philosophical inquiry.

We need art histories that exceed the nation or the region. Such framings are inevitable given that many of the contextual factors (language, history, patronage, circulation, publics ...) that give art meaning have geographic anchors. But national art histories are easily 'captured' by strong states, and dominant institutions.

Dominant national narratives can flatten or erase significant differences. When histories become singular, they are indistinguishable from propaganda—a clear and present danger with national or regional constructs that can be traced back to partitions or colonial or imperial structures of the last 50 to 70 years.

We thus need art histories to be multiple, and enmeshed—and not adhere to national or regional boundaries.

The third aspect for me is that to do something like this—to work on anything that has any pretensions of 'overwhelming' anybody—the effort has to be collaborative.

We thus need to exceed the efforts of single scholars or researchers, the single institution, and even a single discipline. We need to be bold in taking on the difficult and complex challenge of collaboration.

I may be biased here, but I see Asia Art Archive as exemplary of this mode of working. It has already become a significant node within a network of initiatives and efforts, in and outside Asia, collectively working to enable such art histories to take form.

I feel that the work remains largely ahead of us all. But it shouldn't be a lonely journey.

It does this through a tri-partite approach of building collections (increasingly digital) of materials that can fuel these denser histories; hosting the infrastructure (digital and physical) that enables wide and open access; and engaging communities that can both be fuelled by these materials, but also enrich them.

And while there are indeed many more initiatives in Asia since 2000—I feel that the work remains largely ahead of us all. But it shouldn't be a lonely journey.

SACould you tell me about the research project 'London, Asia' you are embarking on with the Paul Mellon Centre in London.

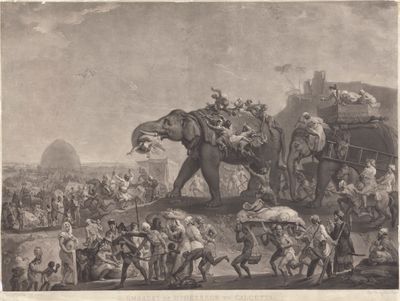

HN'London, Asia' posits London as a key, yet under-explored, site in the construction of art historical narratives in Asia, and examines its influence through an initial set of lenses of exhibitions, patronage, art writing and art education.

'London, Asia' will also reflect on the ways in which the growing field of modern and contemporary art history in Asia intersects with, and challenges, existing histories of British art. It was conceived as a collaborative research project while I was still at Asia Art Archive.

The intention is not to propose a comparative framework, but instead encourage new perspectives on the entanglements, historic and contemporary.

By looking at examples of particular exhibitions, events, institutions, and individuals, this project asks broader methodological questions about the ways in which the art histories of Britain and Asia have been, and are being, written, circulated and negotiated.

Modern Britain, as we all know, was built on Empire. In particular on the century-long sustained transfer of enormous wealth from British India to the Imperial centre.

This imperial looting, enabled by the rapacious capitalism of the East India Company, was integral to financing the industrial revolution, fighting two world wars and building the modern welfare state we call Britain.

We have, however, developed a collective amnesia that blinds us to Empire's complex role in the construction of Britain—leaving it a nation insufficiently imagined.

This is a failure for which cultural leaders, especially of institutions with 'National', 'Britain' or 'British' in their names, must share the blame with politicians.

We envisage that it will fuel symposia, research grants, publications, exhibitions and displays.

The 'London, Asia' project is envisaged as a series of interventions towards making these Imperial entanglements visible; an attempt to spark the process of what Chen Kuan-Hsing called 'de-imperialisation'.

There is no specific end point; rather, these initiatives and resources are intended to open up and fuel generative engagement with an area that art historians, curators and researchers have yet to examine in a systematic and critical way.

We envisage that it will fuel symposia, research grants, publications, exhibitions and displays. —[O]