Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan: Forging Community Ties

Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan (2023). Courtesy Museum MACAN, Jakarta.

Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan (2023). Courtesy Museum MACAN, Jakarta.

Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan's art practice is an integral part of their lives. In 2006, the family emigrated to Brisbane, Australia, packing their belongings in 12 balikbayan (returning home) boxes, which were shipped courtesy of the 2006 Biennale of Sydney as the move became the artwork Project Be-longing: In Transit. Now the artists are packing once more, this time returning to the Philippines to realise their plans for a community art project to skill and support local artisans.

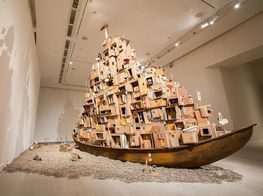

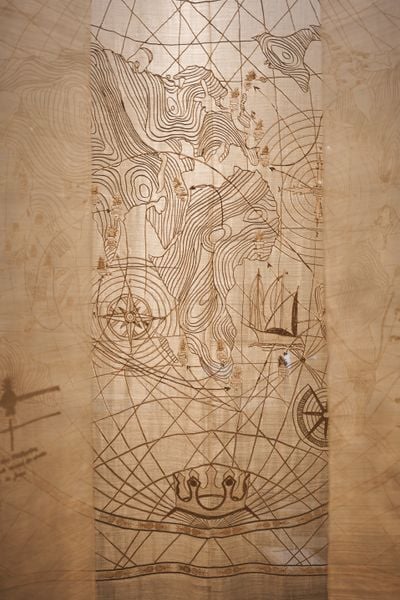

Somewhere, Elsewhere, Nowhere at Museum MACAN, Jakarta (24 June–8 October 2023) is the first survey show of the Aquilizans' 25-year creative practice, which takes impetus and inspiration from the displacement and difficulties of migration, as well as the idea of home. The exhibition showcases installations, sculptural pieces, works on paper, and a new commission, Caged (2023), all constructed from materials that speak to the artists' vernacular—the balikbayan boxes, cardboard, wooden fishing boats, home-stitched blankets, bird cages, and farming implements.

Cardboard is a primary building material for the Aquilizans, with local Filipino connections and international applications that make it a versatile and identifiable choice. For In-Habit: Project Another Country (2010–2023), rambling, miniature cardboard towns and cities, which often feel medieval, ascend from gallery floors, drop down from ceilings, and crawl around walls.

These labour-intensive maquettes, which audiences are invited to help construct, take their inspiration from the artists' lived experiences as well as the local exhibiting environment. In rendering the activity of habitation on a smaller scale, the artists reveal the resilience and industrious activity of everyday life, while also drawing attention to cramped living conditions in many Asian cities and the greater challenges of being human.

The Aquilizans are adept in alchemy and metaphor. In Wings Baanan Series: Baby Wings (2021), a sculpted angel wing is defined by sharp, steel farming scythes, while Last Flight (2009), also resembling angel wings, is made from discarded rubber flip-flops, the evocation of flight offering the possibility of freedom and transformation, and the human becoming the spiritual.

The ongoing 'Passage' series takes the ship as its muse. Made in cardboard and wood, and, more recently, in metal, these vessels are ambiguous entities that sometimes resemble naval warships while at other times the barely seaworthy boats that carry hundreds of refugees.

The long-running series Project Be-longing (1999–2023) uses personal belongings such as blankets and clothing as talismans of community and home, while also linguistically playing on the effort of 'belonging' in a new culture, yet to 'be longing' for one's own home. For the Aquilizans, 'home' is a word under constant construction and deconstruction: what and where is 'home' and what does it mean to be part of a community?

They suggest home can be found in the materials that anchor their work and define our identities and environment from a young age, but also in intimate family relationships. The elusive but inclusive nature of home is hinted at in the exhibition title Somewhere, Elsewhere, Nowhere, which also evokes the generous and international spirit of the Aquilizans' practice.

In the following conversation, the artists speak about these notions of belonging and home, their survey at Museum MACAN, their use of everyday materials, and their familial collaboration.

SAThe title for your survey at Museum MACAN, Somewhere, Elsewhere, Nowhere, encapsulates the transitory nature of your work and practice. How was the title conceived?

AAWell, it came out in one conversation, but we always have titles that have this ambiguous meaning or multiple meanings, where audiences can start to connect with what they've seen or associations they have. It's always good to get them thinking about the title in relation to the work.

The title came from Aaron Seeto, Director at Museum MACAN, when we started working on the exhibition, and I think it fits well with the work that we're showing because when Aaron approached us for this exhibition—

IAIt was during the pandemic, and we were locked down in the Philippines.

AAWell, we were 'somewhere'.

IA[Laugh].

AABut we started asking, where are the works? And we realised, oh, everywhere. That's also the nature of our work because we do work from different locations, with different communities, and collaborate with various people. You don't usually see this in the works, so the exhibition title tells us more about how our art is conceived.

IAThe title is timeless; it encapsulates the essence of everything—our state from the past to the present. The range of exhibited works covers almost three decades, from the 1990s to very recent work.

SAThat's interesting, Isabel. I had thought about the title in terms of place but not time. The idea that where you are is not only a place but a moment in time is thought-provoking.

AAThe title is also about non-specificity—in particular, to time and place.

SAThere seems to be a paradox between this idea of being somewhere/elsewhere/nowhere and the materials that you use, which are often of a particular place and time—materials such as teak and bamboo from Indonesian-made bird cages or found rubber flip-flops littering Filipino villages.

AAIt is very local. Our materials are usually collected locally and talk about site-specificity as well. At the same time, they are also universal as people from anywhere can associate with them because of their broadness.

With the balikbayan boxes, it's the idea of making contact: we're still alive, thinking about you, and sending you things.

We use this strategy for people to connect with us and the work. Using ordinary, banal objects allows people to identify with the work and look deeper to see how it relates to them as viewers and active participants.

Our materials talk about a particular place and time. For example, we're now packing our house in Brisbane to move back to the Philippines using the materials we used when we moved to Australia and we talk about this experience through the materials.

SACould you speak about your use of cardboard? Its ephemeral, everyday reputation belies the fact that it is incredibly useful, durable, and recyclable: qualities that are quite contradictory. What drew you to the idea of using cardboard in your work?

IAIt goes back to our childhood memories, where family members who left the Philippines to work overseas would send cardboard boxes called balikbayan boxes, filled with items for their family back home.

In the Philippines, cardboard is a valuable material; you buy it by the kilo and people earn money from it. It can become the wall of a house, a makeshift space, or a bed. It stood out in our memories, and when we left the Philippines, we used cardboard to move our own household.

AAWith the balikbayan boxes, it's the idea of making contact: we're still alive, thinking about you, and sending you things. The symbolic meaning of the objects in the box is more important than the actual items.

The box also says, we cannot go home, but we can send you this and still make that connection. There are thousands and thousands of Filipinos working and living abroad and every household of Filipinos living abroad has one of these boxes.

We started working with this idea because of issues affecting migrant Filipinos, but then we became migrants ourselves. We moved from the Philippines to Australia courtesy of the 2006 Sydney Biennale; the move and our 12 boxes became the work Project Be-longing: In Transit (2006), shown in the exhibition.

Two years later for the Adelaide Biennial (2008), titled Handle With Care, we made the work Address (2008), using 140 boxes filled with domestic and everyday objects given to us by friends and acquaintances, which were built up to create a roofless house.

That began the series 'In-Habit: Project Another Country' (2010–2023), which was commissioned by the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, and the exhibition with its iterations travelled from 2010 to 2012. From this place (2022), currently showing at the Art Gallery of New South Wales' (AGNSW) new Sydney Modern building, is also part of this series.

Project Another Country corresponded with our move to Australia, referencing the in-between space that opens when you leave home. You're always moving in that middle ground.

SAWas that part of the original idea for Project Be-longing (1999–2023)? What sparked that work?

AADuring the 1990s, everyone was looking into the idea of identity and trying to belong. I think that also connected with the turn of the century and the Y2K panic. Looking back, many artists were working unconsciously in this area.

For example, the 1997 Havana Biennial, which we took part in, was titled The Individual and His Memory. It was very consciously looking into the idea of identity, where the only thing we can cling to is who we are. We started making use of objects to reflect those ideas.

SAHow has the landscape for contemporary art altered over the last 25 years? There weren't many exhibition opportunities for artists in Asia in the 1980s.

AAInitially, institutions, curators, and directors had limited access to Southeast Asia and South Asia, unless they came to do research. I think that encouraged artists to work on what they are and do—to use materials with local content and to focus on the context of the work.

After World War II, many Filipino artists studied in the U.S. and brought home modernism. In the early 1990s, there was a new Indigenous art movement that used local materials as a strategy, defining a regional identity that wasn't Eurocentric, not about Western ideas.

Taking part in those exhibitions gave us more leverage and opened opportunities to see what others were doing. We started looking within: into what we create, the way we uniquely make things, and our methods and processes.

That changes the landscape, not only in the Philippines but throughout the region. In Indonesia, for example, contemporary senior artists and our contemporaries, such as Heri Dono, Tisna Sanjaya, and Agus Suwage, are also exploring their local.

IAI think it's a more challenging time now, but as artists it's normal that we reflect on issues around us and our experiences. The idea of making is a norm in our way of life, which comes out in terms of where we are and who and what we are working with.

The range of exhibited works covers almost three decades, from the 1990s to very recent work.

As we travel, we meet artists—especially third-generation migrants—who would like to go back home to reconnect and discover more of their roots. It's about identity, too, but on a different level.

SAIn your works Habitat: Project Another Country (2015), exhibited at Ichihara Lakeside Museum, Japan, and Pillars: Project Another Country (2018–2023), shown at Auckland Art Gallery, New Zealand, upturned boats hang from the ceiling, sprouting cardboard villages that cascade down to the floor. What was the intent behind this intriguing configuration?

AAIsabel and I think that architecture started with the boat. When settlers arrive on an island, the first thing they do is invert their boat, which becomes the first roof. So, we started working with this idea because it relates to looking for home, the idea of home, and defining what home is about.

We started working on this idea, ironically, in Liverpool, which was a major point of departure for migrants in the 19th and 20th centuries, making Passage (Project: Another Country) (2010) for the 2010 Liverpool Biennial. For that work, we inverted a boat, creating a kind of roof, and that prompted us to keep making installations that relate to these vessels.

We want audiences to investigate their own experience, through their own interpretation, so for the work Pillars: Project Another Country in New Zealand, we looked into the idea of homelessness, which creates another meaning in the work itself.

IAIt's a site-specific work that embodies a pressing issue of that time, when many people lived in the streets because they couldn't afford a place of their own—especially members of Indigenous and migrant communities.

Responding to that experience and the availability of materials, we used cardboard because we see this material as a vessel. We also worked with the architecture of the Auckland Art Gallery, where these wooden pillars cascade from a beautiful ceiling.

AAThe ceiling was designed based on Māori boat-building techniques. So, we had an initial idea, but it started to evolve as we learnt more about the local situation.

SASo, in a way, your local becomes someone else's local as you work in the space where it will be exhibited?

IAYes, we work with the local community, where everyone is welcome to come in and create little houses or objects and start connecting and sharing stories while doing the workshops.

AAAnd through those objects, they bring stories and narratives into the work, and in the process, the work becomes site and space-specific.

SAThe motif of the angel wing is found in a number of works, including Last Flight I-III (2009), Wings Baanan Series #4 (2021), and Left Wing Series (Magdalena) (2023), made with a variety of materials including used flip-flops and metal farming sickles. What significance does this emblem hold in your work?

AAWe like to work with images that recall the idea of flight or plight, as well as freedom and movement.

IAWe made a work in a small fishing village in the Philippines.

AAYes. We helped the village clean up their shoreline, which was full of rubbish. We collected rubber slippers, or flip-flops, and created this installation of rubber slippers perched on bamboo poles, which looks like a school of fish going back to the sea. Again, you see the idea of movement and issues within our immediate environment, and the community learning from and through the art-making process.

We made the same installation in Singapore with rubber slippers collected from prison inmates and the work became about ideas of freedom, confinement, and the plight of the prisoners. So, the context evolves depending on the place, people, and material's origination.

SAIs there a spiritual intent in the use of the angel wing?

AAMaybe. We grew up in the only Catholic country in Southeast Asia and go to church every Sunday as a family. I think that's always in our consciousness and subconscious. And I have always wanted to fly. [Laugh].

SAAnother symbol of flight is noted in Caged (2023), a work shaped like an aeroplane wing, made of teak and bamboo bird cages. Could you speak about this?

AAWe've been working with the form of an aeroplane wing for some time. The idea for Caged was conceived during our 2015 residency in Yogyakarta, but it only materialised through the Museum MACAN show.

We investigated the idea of the bird cage because it's a tradition in Indonesia to keep a pet bird, and almost every household has a bird in a cage. Aesthetically, it's a beautiful thing, but it also produces ideas of freedom and confinement. It's also a refuge where one can feel safe.

Caged consists of 93 specially constructed bird cages locked together to form a single aeroplane wing. We collaborated with artisans in Yogyakarta who made the cages, specifically asking them to use recycled teak wood sourced from old furniture and demolished houses, so the work also talks about environmental issues.

Poachers travel to the birds' natural habitats in Sumatra and other parts of Indonesia, capturing and selling them in the markets as pets and to be bred for popular bird-singing contests held throughout Indonesia and in other parts of the world.

The installation also includes a sound component; we found tape recordings of bird-singing contests which are used by poachers to attract and capture birds. So, the form of a single aeroplane wing made entirely of bird cages signifies the idea of non-flight and indirectly talks about the idea of involuntary migration.

SANot only do you both work together, but you also include your five children, who are all artists, in your practice. How does this relationship operate?

IAYes, the collaboration has expanded and become a family thing. It's an opportunity for us to come together and build and create something. The kids always joke and say, 'Mom, Dad, we don't have a choice, right?' But they grew up in that environment.

When they were little, we recreated our house in a museum as an installation work. We slept in the museum until the opening, making a sound recording of the entire stay, which could be heard by audiences as part of the work.

The work we made for AGNSW is another example of us coming together to work as a family, after being separated during the pandemic. Alfredo and I were in the Philippines for nearly three years and the kids were all in Brisbane. The Sydney Modern installation became our reunion piece.

AACurrently, we are doing the reverse of what we did for the 2006 Sydney Biennale: packing our home in Australia and moving back to the Philippines. During the pandemic, we started numerous projects working with and helping artisans in our studio's region, assisting not only financially but helping them build and equip their workshops.

The Philippines will be a home base to focus on these community projects. It's a new trajectory in our practice where we're creating and building something for the artisans to transfer skills and knowledge to the next generation, sustaining declining and vanishing practices and empowering a thriving community in the process.

We've been creating works all over the world and now perhaps it's time and there is a need for us to go 'home' and focus more on our own local and immediate community, to see how our work will evolve and take on a new form. Perhaps, in these trying times, we need to invest more in relationships. That's very important for us. —[O]