Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Temitayo Ogunbiyi's Distinct Cosmopolitanisms

In Partnership with Blanton Museum of Art

Left to right: Njideka Akunyili Crosby; Temitayo Ogunbiyi. Courtesy the artists and Blanton Museum of Art.

Left to right: Njideka Akunyili Crosby; Temitayo Ogunbiyi. Courtesy the artists and Blanton Museum of Art.

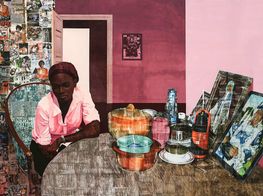

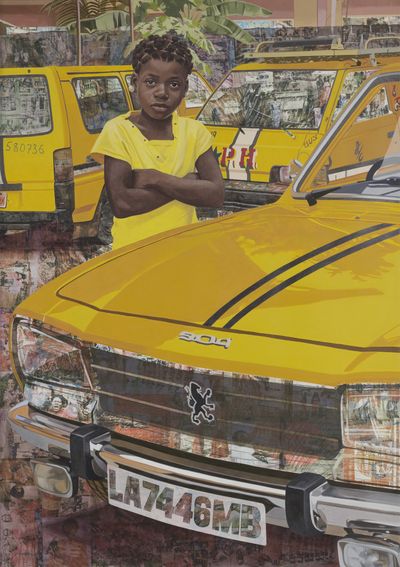

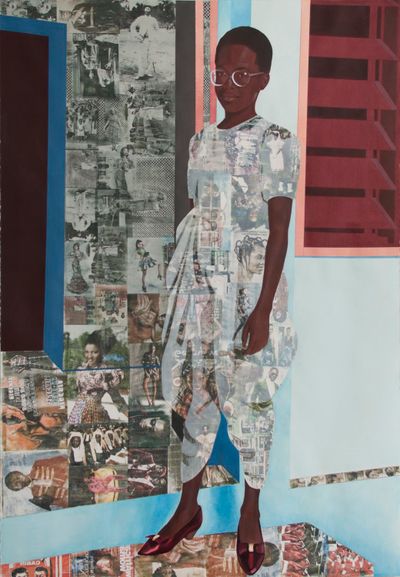

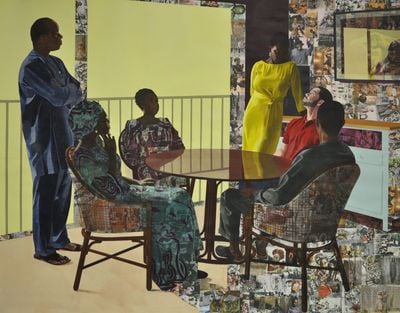

Njideka Akunyili Crosby's distinct figurations, the subject of a travelling exhibition curated by Hilton Als, beginning at Yale Center for British Art, New Haven (22 September 2022–22 January 2023), express a contemporary cosmopolitanism rooted in the artist's move from Nigeria to the United States.

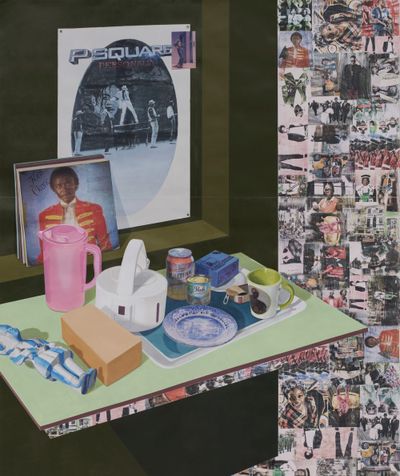

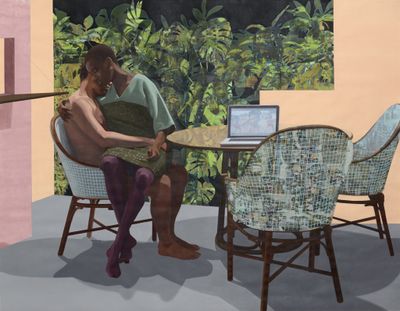

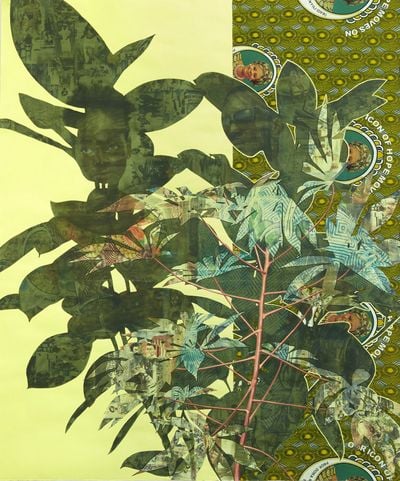

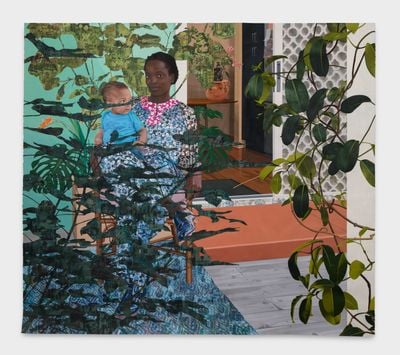

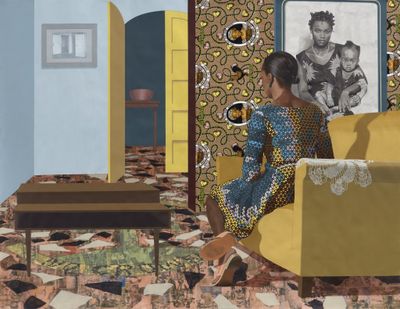

Hinting at nostalgia and resolution, Akunyili Crosby's large-scale works reflect the complexities of cultural multiplicities, with the artist's signature collage and photo-transfer technique seamlessly integrating images from magazines, newspapers, and self-taken photographs of Nigeria to contour figures, plants, and domestic interiors.

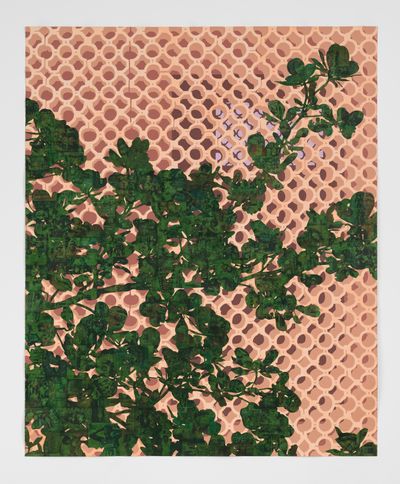

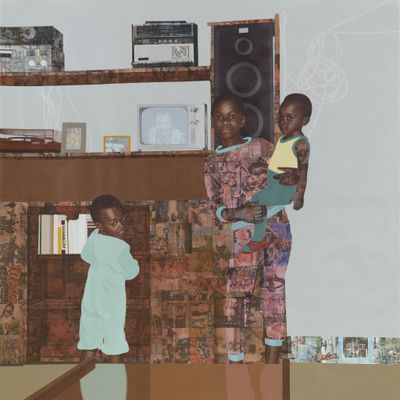

Four of these paintings are presently on view at Blanton Museum of Art (23 July–4 December 2022) at University of Texas, Austin. Lush vegetation known to Nigeria takes centre stage, reflecting the artist's ongoing interest in plant life since 2015.

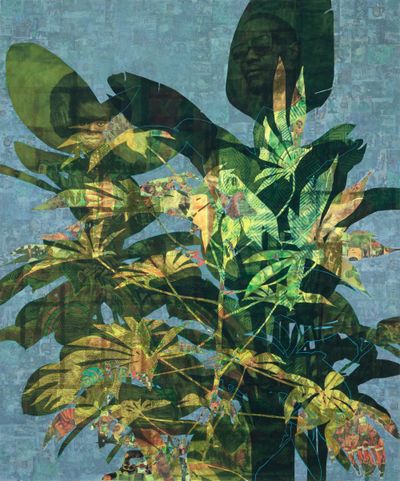

Among them, Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens (2021), confronts the artist's current life in the United States. Against a blue-green wall, the artist, wearing a floral dress partially covered by a lattice of growing leaves, sits on a grey backyard patio in Los Angeles holding her young child. Within the dense foliage swallowing both figures are familial photographs and archival images of her native Nigeria.

The image was made in the advent of her mother's death, prompting her to create imagery of motherly affection. The addition of her young son, who reminds her of her late mother, seems to reflect on the cultural shifts from one generation to the next.

Born in Enugu, Nigeria, Akunyili Crosby grew up in Lagos, later moving to the United States to study medicine in 1999. Prompted to share Nigeria's stories, the artist took her first painting class at the Community College of Philadelphia, before attending Swarthmore College, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and Yale, where she completed an MFA in 2011.

In 2015, Akunyili Crosby held her first solo exhibition at Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Curated by Jamillah James, The Beautyful Ones featured intimate portraits of friends and family members that presented a 'counter-narrative to the often-troubled representation of Africa's complex political and social conditions'.

Across paintings, visual references to the Nigeria's plant life, popularsingers and old television shows are imprinted on bodies and backdrops like wallpaper. This abundance of imagery speaks to the artist's understanding of Nigeria as a 'contact and confluence zone', where local cultures merge with influences from colonial Britain and popular culture later imported from the United States.

That sense of cultural and historical enmeshment extends to Akunyili Crosby's interest in the origins of plants. In East L.A., she noticed an abundance of plumeria, a flower endemic to Central America and the Caribbean that were transported by migrants as reminders of home. 'When you are an immigrant, no matter where you are, the histories and the cultures of where you grew up are always withyou', Akunyili Crosby says.

In this conversation, Crosby speaks with Lagos-based artist and curator Temitayo Ogunbiyi, whose work similarly reflects on migration, anthropological histories, and botanical cultures, across painting, sculpture, and installation. Both artists operate within an entanglementof inheritances and experiences that motivate inquiries into categorisation and identity.

Born in New York,Ogunbiyi is known for functional playground installations that enmesh different references within their steel bars, from studies of braided hair to travel routes. A recent iteration was installed at Museo d'Arte Contemporanea Donnare in Naples—a nod to self-made gym equipment that men in Lagos assemble, such as dumbbells made of buckets and bars.

Published in partnership with the Blanton Museum of Art with a public Q and A moderated by Claire Howard, Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Temitayo Ogunbiyi speak about growing up in Nigeria, their shared interest in plant life, and how diverse cultural threads and processes are carried into both of their practices.

TOWhat does this exhibition at Blanton Museum of Art mean to you?

NACThis is a collection of paintings I've been working on since 2019, from when I visited Nigeria. I first introduced plants into my work in 2015 and it's something I've been slowly exploring more. This show feels like the pieces I've been chasing for years.

TOThat's the perfect segue into Persistence of Vision: Screen Walls & Fruit Tree (2022). I love this work so much—the title could be read in so many ways.

Maybe it describes what it means to strive without being able to see what's ahead, or the life of an artist. Could you tell us about how this work came to be?

NACThis is one of my absolute favourite pieces. It's from a picture I took of a house in my ancestral village. It's also an architectural form that is very prevalent in Nigeria, especially in houses from the 1970s to the early 1980s. When I think about the memory bank I carry from growing up in Nigeria, the screen wall plays a huge part, as does the plant in front of the wall. In Nigeria, we call it a fruit tree because it is ubiquitous.

For the longest time, I wanted to do something with the screen wall, a top-down, side-to-side, full piece. The title, Persistence of Vision, speaks to this return and, like you said, does a dual thing. It happens when you're looking at something: you close your eyes and still see it in your mind. Although I'm not living in Nigeria, this vision of Nigeria stays with me.

TOWhen I saw this work, you had just made a huge change, despite being nearly at the end. Could you tell us more about this change?

NACThis piece looks simple but was very difficult to make. At some point, it had me sitting in the corner of my studio with tears in my eyes. I will explain and you will understand why. I knew how I wanted the piece to function in terms of optics. I wanted the plant to be a silhouette in front of the screen wall, but I also wanted the screen wall to glow. This 'glow' would be achieved through a transparent wash of paint.

Persistence of Vision has to do with optical play. The space through the screen wall would be dark and painted opaque and I wanted an even darker hallway behind this space. I needed the three shades of paint on the sides of the screen wall to be dark enough that they fall back, but not so dark that they begin to compete with the tree.

I had a very narrow range of values to work within and had to make the shades hit exactly where they should. To make this piece, every edge was taped off. I have two incredible people who helped me in the studio, Shaun and Molly, who took the tape off and ripped off all these edges.

When I'm doing this aforementioned wash on it, I'm doing it from faith, as I can't see the rest of the work. I had done a Photoshop sample and felt confident about the process, so I mixed this orange, but when I took off the tape, it was too dark. I was in shambles because I didn't know how to fix it.

The easiest solution would be to paint over it with an opaque, but I couldn't because I wanted the face of the screen wall to be translucent. This way, when the light comes through and hits the whites of the paper, it does a quick bounce back to the eye, which will give the screen surface this glowing quality that really helps silhouette the plant.

We ended up taking a sharp blade to cut around everything. We used tape to peel off the paint, almost like you're taking a surface off the paper. It set me back a month, but I was happy I did it.

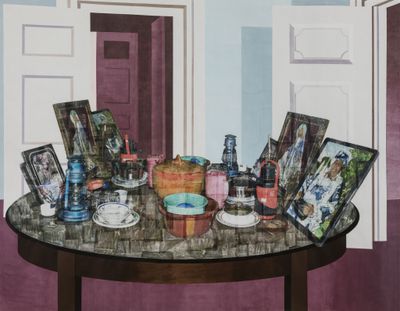

I think this leads into your work because something we both think about is a specificity of things—objects, plants, buildings—that locks people down or roots them in time and place, which you do in You will labour to find value anew (2022).

TOYou will labour to find value anew is a piece that I've wanted to do for a long time. The objects I have cast are called grinding stones, which in South West Nigeria and Eastern Nigeria, are used to grind plant matter, tomatoes, pepper, and okra in preparation for stews.

The entire work is ten metres high and I've used reconstituted gas and water tap heads, which are an essential part of everyday life here.

In my practice, I like to think about how to represent the labour of motherhood and women.

I wanted to highlight this very significant object that captures our culture and has become less popular with the advent of the blender. But it's still an interesting cultural anchor across Nigeria and other West African countries, where similar sorts of objects are used to manually grind plant matter.

Every grinding stone is engraved with 'Sweet Mother', which has different references. In my practice, I like to think about how to represent the labour of motherhood and women.

With this piece, I felt like I was able to represent lineage for the first time. It made me think about how many mothers' existences went into my existence, contributing to the existence of future generations, and what it means to come from a line of people.

I'm very interested in how we can use lines to represent all sorts of things from plant fibres to navigation paths and hair strands, and where these lines collide.

NACWere you also thinking about the highlife song, 'Sweet Mother' (1976)?

TOAbsolutely. It was played several times in the gallery, which adds another layer of significance.

NACThere are elements in your work that parallel what I'm interested in, so I feel an affinity for you in terms of how these pictures, words, sounds, and phrases are tied to so much memory or history, either for people who grew up in Nigeria, or whose parents grew up in Nigeria.

'Sweet Mother' is among the most successful and popularised highlife songs across the African continent. I listen to this song a lot when I work. Looking at your work opens something else; you begin to hear music or see a video play in your head. Very sentimental!

TOFor Persistence of Vision, how specific were you about the type of image you wanted and needed in planning the composition of that work—the fruit tree, specifically? Was this during the pandemic, or shortly after?

NACIt was during the pandemic. I knew I wanted a fruit tree. Normally, when I need certain plants, I search online. But it's difficult because of the way Google works. You can only find something if it's been tagged.

For instance, somebody in Nigeria who takes a picture in front of a fruit tree is not going to tag the tree because it's so common. I was thinking about it and realised that if you're in a place like Lagos, you're probably never more than 400 metres away from a fruit tree. I reached out to Tayo, who connected me with someone who went around Lagos and sent me like 1000 pictures of fruit trees.

One of the ways we've connected is through our love for plants, which can be such an interesting way to think about mapping people's movements across the world. It is interesting to us both because we have moved in various ways.

We went to my ancestral village on weekends, and I always knew we had left Enugu and started arriving at the village once I saw cassava plants.

I grew up in Nigeria and now live in the United States. You were born and raised in the United States and now live in Nigeria. When people move, plants are something they take with them as a reminder of where they came from, to the extent that these plants are like cosmopolitan distributions because they've moved through so many places.

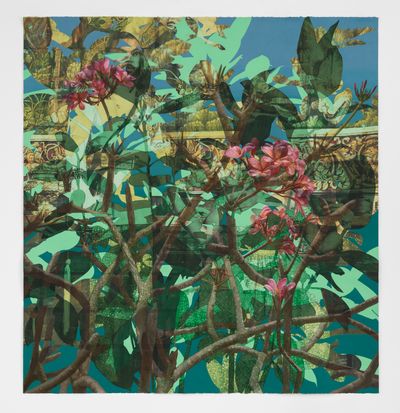

Dwellers: Cosmopolitan Ones (2022) is a piece in the Blanton show and a sibling to Dwellers: Native One (2019). From 2016 to 2017, I did a show about pairs of works, and this was the last pair that was never finished.

I was thinking about plants and the specificity they carry. Dwellers: Native One has cassava plants, as well as ugu, known as the fluted pumpkin, and the Caribbean almond. These plants might not be endemic to Nigeria, I think cassava started off in South America, but at this point, Nigeria is the world's largest producer.

These plants are like cosmopolitan distributions because they've moved through so many places.

Its relevance ties not just to Nigeria, but a specific part of Nigeria. Growing up, we went to my ancestral village on weekends, and it was a marker for me. I always knew we had left Enugu and started arriving at the village once I saw cassava plants. Cassava roots are also a big part of Nigerian diets, especially in some parts of Eastern Nigeria.

I was thinking of cassavas at this point, almost being native, and the fruit tree as well. The counter-piece to this is Dwellers: Cosmopolitan Ones. With this, I was really fascinated by the terms used for plants that have become naturalised in other places, like plumeria.

The plumeria plant is a pink flower from Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. It has become naturalised in different places, including Nigeria, where it's grown as a cosmopolitan ornament. This work includes the plumeria plant, the fruit tree, and the Indian rubber tree, which is native to India but has become naturalised in different parts of the world, including the United States.

TO'You will order taxonomies according to your days' (2021–2022) is an installation from the recently concluded Berlin Biennale. I was very interested in looking at biodiversity; ugu and cassava leaves both feature in this suite of 52 works on paper.

These works attempt to document my interpretations of green vegetation that grows in West Africa and the Caribbean, which is often substituted with this image when persons from these places end up living abroad, in the West specifically.

For example, the vegetable callaloo, known as amaranthus, is something my mother grows outside of Philadelphia and her friends grow it in New Jersey. It's an anchor for them; having this vegetable available makes a home.

This series' title 'You will order taxonomies according to your days' relates to how knowledge of plants is archived. These are works on herbarium paper, which has been used for centuries to mount, store, and organise plant specimens.

This particular paper size has come to inform the folder, drawers, and architecture of herbariums around the world. Part of why I work on this paper is to bring conversations from South West Nigeria, Nigeria at large, and the Caribbean into dialogue with Western taxonomies.

Another plant that's represented is okra. I tried to chronicle the plant in its growing states and as it is prepared for cooking. I challenged myself to draw powdered okra, and raw and cooked okra—thinking of the many states in which we experience plant life. Interestingly, I started working with plants in 2016, not long after Njideka. It's become a pillar of my practice.

NACWhen you talked about your mother and her friends growing plants in different places, I was reminded of how my interest in plants started. I had just moved to Los Angeles and I had a studio in East L.A. I would notice this particular plant every time I walked to my car.

It turns out we have plumeria in Nigeria, but I never saw it. I only noticed because I had a friend helping me in the studio who loves plants. I started seeing it everywhere in East L.A. but not outside of it. Then we saw a beautiful plumeria tree in someone's yard. We spoke with her and she said this plant reminds her of home.

Plumeria is native to Mexico and Central America, and East L.A. has a big Central American and Mexican population. I imagine the plant is so prevalent here because it's planted to remind people of home. Then, I started thinking, what other plants do that? That's how my plant journey began.

Another story I shared with you is about this fish we eat in Nigeria, opmaroku. I always thought of it as a local fish; it's not very expensive and you eat it in the village with traditional soups. Then about a year ago in Los Angeles, I ordered this meal.

I can't remember what they called it, but it was salted cod. I ate it, turned to my partner and said, 'Justin, this is opmaroku! We eat this in Nigeria.' I was obsessed with this. I thought, I am not misremembering: this is the taste of that village fish we eat.

I'm interested in how culture morphs, moves, and swallows new things to make them its own.

When I looked up cod and saw that it only exists in Norway, I thought I was losing my mind. There's no way this fish can just be in Norway unless there's a Nigerian fish that has the same taste. And then, of course, I went down the Google rabbit hole.

I realised that opmaroku is actually cod. During the Nigerian Civil War, there was so much malnutrition in Eastern Nigeria. Kids needed a lot of protein, so missionaries in Europe sent dry fish to Nigeria. And now that has become part of our culture.

I'm interested in how culture morphs, moves, and swallows new things to make them its own. Nigeria is such a fascinating place for it because we used to be a British colony. So you have things that came from England, from the United States in the popular culture we consume, and then you find random things like this.

All these things have mixed into this new thing, and it keeps changing. Every time I come back to Nigeria, I meet a different country.

TOThat's great.

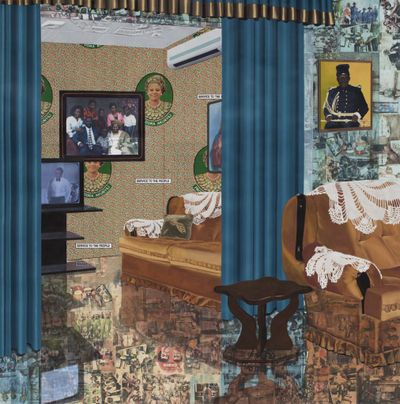

NACOne of my paintings is titled Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens. Different themes here tie into mothering and memory, which we've talked about. But with this piece, I also thought about how colour is tied to memory. In Eastern Nigeria, the ground has this rich, reddish-orange colour that I tried to capture. You see it in this emogu pot in the background.

There's also this minty blush colour I return to. I've been watching old Nigerian TV shows and it appears in many interiors, such as in the show The New Masquerade. In Rattlesnake (1995), you see this minted green; in the new Living in Bondage (1992), this deep cerulean blue.

There is almost this memory bank of colours that I keep swimming around when I make a piece set in my current house in Los Angeles, thinking of how the past and the histories we carry are always with us. Do you want to talk about colour in your last set of works?

TOColour, mothering, and memory. During the same studio visit, I saw Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens—another incredible title. It wasn't finished, but the orange flower really entered my eye, and I couldn't shake it from myself.

This year, I finally completed this work, where I challenged myself to think about how many botanical forms I could connect to this orange colour. One of them is ripe bitter gourd, which grows here and in Southeast Asia. It's a very popular plant in Indian street food and curries, but it also grows in the Caribbean. I was first introduced to it by my mother.

Thinking about motherhood, I began designing playgrounds in response to their lack in Lagos. The few I had seen were second-hand plastic objects imported from the West. I want you to think about sustainable options for play that respond to the history of hair styling and the lay of the city, thinking about how we interpret roads and the paths we take every day.

The lines that you see here take on a number of references, from the lines of plants, which I also thought of in relation to Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens, but also lines that I lift from map applications and Google Maps that suggest paths from one point to another.

In You will play in the everyday, running (2020), the referenced paths connect Lagos to Naples, which is where the eponymous exhibition took place in 2020. The curated garden in the back included plants that I know to grow in both cities.

NACThese are fascinating. Can you tell us more about your upcoming project? I know it's going to be playgrounds, but plants are going to feature more prominently.

TOI have an upcoming exhibition opening in a couple of weeks, at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. I will be presenting a new playground as a three-part community garden. It's my most ambitious and interactive plant installation to date. I'm also preparing for an exhibition at the Noguchi Museum in New York, as well as a couple of permanent installations in Lagos.

CHWe have a few questions from the audience. The first one relates to what you mentioned about memory, Njideka. And this is a question for both of you: 'What are the types of emotions or thoughts you want to follow people as they experience your art and content? Do you consider your audience during the process, or is it more of a personal journey?'

NACFor me, it's a personal journey, like with the screen wall. I'm chasing things I've wanted to see and make in my head.

As I start making it, I'm conscious of this dual audience that will see the work, or how it can be interpreted. On one part, I put in little games, treats, and nuggets for people who grew up in Nigeria in the 1980s and 90s—references to something like 'Sweet Mother' that'll trigger a song, a TV show, or popular people we all knew and maybe looked up to.

For instance, part of the title Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens comes from a Mamman Vatsa poem. If you remember Mamman Vatsa, there's a whole other door that opens the conversation to how he was murdered, the Nigerian dictatorship, and what it meant to grow up in Nigeria when you could turn on the TV and find out that your favourite kids' author has been executed because he was suspected of plotting a coup.

But if you don't know that history, there is another part of the work that is engaged in the history of painting, how images are put together, and this play between drawing, printmaking, photography, and what I'm doing with the surface.

Standing in front of Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens, I almost think of my eyes like a camera that is re-adjusting, re-focusing, and thinking of what I can do to the surface to bolster it—whether it is putting something transparent in front of a transfer, or next to something opaque, or a surface that is treated in a different way. So as your eyes move across the work, not only are you doing jumps in ways of image-making, but of what's being depicted.

Even if you don't have that backstory, the work exists as a painting and work on paper that I've thought carefully about. You can enjoy it visually and in terms of what's happening to your eyes with optics.

TOI agree. While it's very much a personal journey for me—my practice, where I choose what I want to present and how I want to present it—the conversations I have with people who view my work and those I encounter in my every day certainly impact my thinking and open my mind to new possibilities in terms of references I might make.

I've been gifted several fantastic publications that document different plant histories, for example, that have really opened my eyes to how much more there is to learn. I'm always keen to create work that generates conversation with new audiences and feedback that I can use to carry my practice forward. I think of it as a dialogue.

NACOn the kind of memory I want to evoke, I feel like there isn't a specific memory. I'm not thinking, I want people to feel this emotion. Humans are complex.

I think about the complexity in my own life. I live in the United States now, where I moved when I was 16. I grew up in a very little town in Eastern Nigeria that was incredibly homogeneous. I went to boarding school in Lagos, which is incredibly cosmopolitan. My world expanded in terms of the different people I met there, of different ethnic, religious, and socio-economic groups.

Likewise, thinking of Nigeria's history as a British colony and how the culture is complicated by this influx of American and different European cultures. Even within this country sectioned off in 1914 by Lord Frederick Lugard and called Nigeria, there are 200 ethnic groups that borrow from each other. For instance, when you do a traditional wedding, Igbo people wear coral beads, but it's not Igbo culture. It's from the Benin area.

I grew up in a military dictatorship until 1999. In my daily life, people talk about dual consciousness. Mine is almost like a multi-consciousness. I'm always seeing life through my Nigerian background, Nigerian lens, and newish-American lens.

In Cosmopolitanism (2006), Kwame Anthony Appiah talks a lot about how far back contact goes ... He really talks about it like an onion.

You carry your history with you, and of course, your parents' history. Tayo, we've talked about this. Thinking of the Nigeria in which my parents grew up, it was vastly different. My grandmother remembers waiting for the queen when she visited Nigeria in 1956.

It's such a rich, convoluted history, from my grandmother who lived and died in the village not speaking English, to my parents who grew up in the village but went into towns for secondary school and university, and me, growing up in a town, going to Lagos, and leaving the country.

CHWe have a question that builds on that: 'Do you think that in both your practices, you are amending and re-establishing the real purpose and function of flora-fauna objects and cultural practices that were misunderstood and misinterpreted through the lens of Western art history? For example, applying the term 'African art' to these things before the modern and contemporary art expressions of the 20th and 21st centuries?

TOI've always had challenges with the word 'real' because a lot of what we see, look through, and live in, is very constructed. In my practice, I'm keen to show how little one can know and challenge the idea of categories, which have always existed to organise knowledge.

These categories become more interesting when we try to open them up, realising that they are anchors of Western pedagogy. But there are also other knowledge systems from which to pull and interpret—to plant knowledge, especially.

Okra, for instance, is the one plant found in the cuisine of arguably every ethnic group in Nigeria. That fact made me endlessly curious about the many interpretations and applications of the plant I could learn about and think through.

In generating conversation, you begin to confront unchallenged notions of history and knowledge, which change based on who is telling the story. I'm grateful for the opportunity to share the knowledge that I've stumbled across in my practice and life through my work.

NACI may have a shorter answer: I don't know. This might be a question I will think about for the rest of the day; something I grapple with is how much more complicated things are.

In Cosmopolitanism (2006), Kwame Anthony Appiah talks a lot about how far back contact goes. Even when you think of local histories or the origin, there might always be another layer. He really talks about it like an onion.

For instance, kente cloths are thought to symbolise parts of Ghanaian heritage, but the silk used to make the cloths come from somewhere else. The fabrics I grew up thinking of as African fabrics actually come from Holland. So I think of my works as my thoughts made concrete. In certain works, there are many iterations, because I keep thinking, learning, and changing.

CHThere have been a few questions, Njideka, that allude to the visual complexity and density of your work. Could you explain your process?

NACI came ready for this because this question tends to come up. Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens started as a stick figure drawing of me sitting down with my legs crossed with plants in front of me. The kid was added later, after a studio visit during which I thought about motherhood and generations.

During that studio visit, I talked about my mom who died in 2014, and it ended up being very emotional. My youngest kid sometimes reminds me of my mother, so after that visit, I decided to add him to the piece to make this generational connection.

I figured out what I wanted both of us to wear and recruited my husband and the lady who helps take care of my kid to do a photoshoot. She tried to get him to look the way I wanted, and my husband took the pictures.

I start with a very rough drawing, then I go to my image bank to pull up trees. I put the plants on tracing paper and position them. The next part is figuring out where the transfers go. I wanted them to flatten the fig tree, my outfits, and the plant in the background, but based on the washes I put on them, they separate again.

It's all taped off, then the images are transferred. I put the wash on the dark piece and back piece, and try to figure out the colours. I didn't end up with this colour scheme, so it's a lot of Photoshop work and piecing different things together. —[O]