Jean-Michel Othoniel on the Disturbed Geometry of Gardens

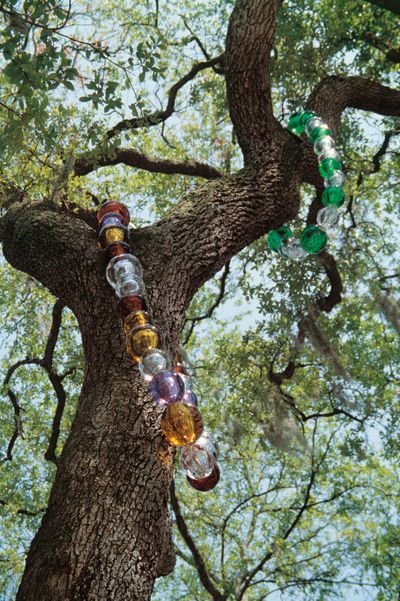

Jean-Michel Othoniel. Exhibition view: The Flowers of Hypnosis, Brooklyn Botanic Garden, New York (18 July–22 October 2023). © Jean-Michel Othoniel/ADAGP, Paris, and ARS, New York 2023. Courtesy the artist and Perrotin. Photo: © Guillaume Ziccarelli/BBG.

Jean-Michel Othoniel. Exhibition view: The Flowers of Hypnosis, Brooklyn Botanic Garden, New York (18 July–22 October 2023). © Jean-Michel Othoniel/ADAGP, Paris, and ARS, New York 2023. Courtesy the artist and Perrotin. Photo: © Guillaume Ziccarelli/BBG.

When Jean-Michel Othoniel was provided the Petit Palais for a survey show in 2021, his exhibition The Narcissus Theorem (28 September 2021–9 January 2022) became one of Paris' most talked about cultural experiences of the year.

Spurred by the sensation of making sculptures for the museum's elegant garden, the French artist was motivated to create more massive floral forms for Treasure Gardens (16 June–7 August 2022) at the Seoul Museum of Art and Imperial Palace Garden in Seoul, and The Flowers of Hypnosis (18 July–22 October 2023) at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden in New York.

In Brooklyn, six site-specific sculptural flowers—including the artist's most monumental to date—sparkle under the nurturing sunlight while engaging the garden's architecture and manicured nature. Creating luminous works to convey optimism, Othoniel cultivates beauty to seduce viewers to look at his art long enough to absorb his subliminal ideas and concerns.

Othoniel's first public art commission stands at the entrance to a Paris metro station near the Louvre. Twenty-three years since it was installed, it remains one of the city's most popular public artworks.

He began Le Kiosque des Noctambules (Kiosk of the Nightwalkers) (2000) in 1996, while in residence at Villa Medici in Rome. Four years in the making, the result is a whimsical glass and aluminium double canopy covering the Palais-Royal station.

Undertaking the project transformed Othoniel's practice, showing him what could be achieved through collaboration with a team at scale. Working with artisans, architects, and engineers on multiple projects over the next 25 years, he was able to more readily explore the passions that he had been developing since his youth and across his career.

Born in 1964 in Saint-Étienne, France, Othoniel studied at the experimental École nationale supérieure d'arts de Cergy-Pontoise, where he learned to create art in a variety of media. Graduating in 1988, he had his first solo show in Paris the following year and gained further international attention after participating in documenta IX, curated by Jan Hoet, in 1992.

Engaging with the exhibition's theme, From body to body to bodies, that was partly influenced by the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and 90s, which was a focal point for much of his art at the time, Othoniel presented poetic, corporeal sculptures in wax and sulphur. In French, the word for sulphur is similar to the word for suffer, which many victims of AIDS did.

In 1993, Othoniel started working with glass, which expanded ways for him to make emotive art. Through glass, he began to develop a formal language that embraced beauty, exploring themes of love, absence, and loss.

Inspired to be unafraid of beauty by artist Félix González-Torres' reading of minimalism, with his beaded curtains and accumulations of candies, Othoniel soon turned Murano glass beads into dreamcatchers and symbols of hope.

The glass works evoke beauty and seduction, but the artist's pearls aren't perfect, rather slightly injured or scarred. Exhibiting at Venice's Peggy Guggenheim Collection in 1997, Othoniel hung his beaded sculptures in the garden's trees like giant trinkets or forbidden fruits.

'My challenge has always been to make each necklace different, in terms of size, colour, and rhythm,' the artist explains. Building on that idea, in 2002, he was invited to show in the New Orleans Museum of Art's sculpture garden, where his body-length necklaces took on meanings more related to the city—recalling the beaded necklaces tossed from community floats as symbols of faith, justice, and power during Mardi Gras.

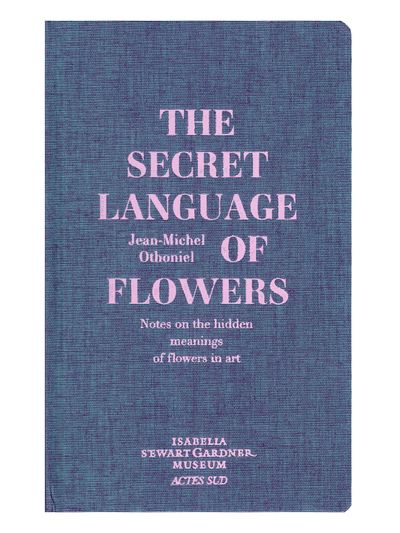

Fascinated by gardens and plants since childhood, when he helped his grandmother tend her garden, Othoniel researched flowers in art during his residency at Boston's Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 2011. He published three editions of The Secret Language of Flowers, the second of which is illustrated with artworks from the museum's collection, and had a solo show of his flower sculptures there in 2015.

During the same residency, he started research on a fountain commission for Château de Versailles near Paris. In 2015, his gilded glass sculptures became the first permanent artworks added to the gardens since the days of Louis XIV.

In 2021, the artist took over the Petit Palais museum and garden for his biggest show in Paris since his 2011 retrospective at the Centre Pompidou.

The exhibition The Narcissus Theorem showed his geometric knots and flowers made of glass and stainless-steel beads, as well as glass brick blocks and floor pieces, which reflected light like flames and flowed like water across the galleries and down the stairs of the building's grand entrance. The visual delight, which this impassioned artist created for that Beaux-Arts palace in Paris, continues to glow in his latest sculptural pieces today.

In this interview, Othoniel speaks with New York-based writer and curator Paul Laster on his long career, discussing seminal works and his interest in gardens, the concept of emotional geometry, and the role of symbolism in his work.

PLGardens have become natural homes for your works. Do you remember the first garden that had an impact on you?

JMOMy grandmother had a garden with vegetables, fruits, and flowers to put on the table. I spent a lot of time helping her in that garden every summer when I was a child. I was from Saint-Étienne, so going to the small city of Cusset and spending time with her was impactful for me.

Years later in 1988, I visited a garden in Japan. It was a mind-blowing experience—it was so perfect, so contemplative; I was very impressed. From then on, I went to see gardens in every city I visited—gardens and flea markets. It was my way of connecting with the spirit of a city and its people. You can sense how the people are living and understand what they love.

PLHow do you define 'emotional geometry', a term often mentioned in relation to your artwork?

JMOI think it's about having a poetic vision of the world. I did a piece called Géométries Amoureuses (Love Geometry) some 20 years ago, based on the idea of emotion-disturbing geometry. The beads in the artwork are not regular. It's not purely geometric, but a disturbed geometry—more related to the human body than to abstraction.

PLWhen we spoke at your 2012 survey at the Brooklyn Museum in New York, you told me about the influence of Félix González-Torres and the impact of the AIDS crisis of the 1980s on your work. Could you elaborate?

JMOFor me, Félix was a genius. He broke all the rules, bringing emotion into abstraction and poetry into minimalism. It was important because it was linked to AIDS, to my generation, and this fear of love.

This is also part of my work, and partly why I was invited in 1992 to documenta IX, which was about the impact of AIDS on the body, the vision of the body through publicity, and how bodybuilding became important. Now, people are interested in rebuilding it. It's strange to me that everybody has a tattoo; it's like the body has taken on a new layer.

PLWhat role have geometric forms, like the circular beads that you have continued to use, played in the making of your works?

JMOI've taken different approaches. My work began in the 1980s with the idea of the body, which is why the beads are irregularly shaped, like body parts. They are all handmade because I want them to be imperfect—I want them to show scars and deformation.

Now abstraction has entered my work, mainly through my research with a mathematician in Mexico, which linked my work to the cosmos. I love it when you see yourself reflected in the beads; it's like you are in a universe with stars surrounding you. I started with something very sensual, very organic, and arrived at something much more abstract, more geometric.

PLHow did your work change when you started working with Murano glass beads?

JMOI started to work with artisans. I needed someone to interpret my work and build it because I was not able to blow glass myself. I always say that I reached a point in my work where I started to be like a maestro. I have to write a score and then find the right interpreter for the work. Like a composer, I have to work with other creative people.

Mistakes are always so interesting. I want to use them to achieve something new, not just perfection.

PLYou are creating the notes of the composition. You're telling them to make these things in these sizes and colours. Then they come to the studio and you put them together in a way that you've conceived, right?

JMOYes, and I stay involved with every step of production. I'm always paying attention to what everyone is doing. I'm behind the guy who's on the computer and following the guy who's making the plans. I cannot control every aspect of what they do, but I want to be part of it.

I don't want to say, here is the drawing, now make me a sculpture. I'm following the creative process, and I do it for one reason: because of mistakes. Mistakes are always so interesting. I want to use them to achieve something new, not just perfection.

PLWhat's your favourite way of shaping the beads and what do the various forms signify for you?

JMOThe form that I really love is the necklace. It's a model I'm using to make my necklace-like, beaded sculptures. It's a great way of working, as I can go from small-scale to large-scale pieces. It's representational yet totally abstract; when you hear the word necklace, you think of a small thing, but my works are quite big. And it's something you find in so many civilisations and countries. Through these very minimal pieces, I have a connection with people in Asia, South America, and Africa.

PLAfter working with glass beads, you decided to make glass bricks. Did that expand your work in another way?

JMODiscovering bricks in India that I wanted to make with glass was a step toward the idea of construction and architecture, and to space that you can enter. Being in an installation made with bricks, you are in a space that can protect you. It's the same feeling as being in a garden—to be out of the normal world, in a very contemplative way.

PLAnd the discovery of the brick and your concept of creating the glass brick came about by chance, right?

JMOYes, it came about through the observation of nature. That's why I'm always paying attention to the real world. When I was travelling in India, I saw piles of bricks all along the road waiting to be used to build houses. It was a poetic shock. People gathered bricks to build their own houses. I felt their energy of hope, which pushed me to create my glass bricks.

I went to India because of their sensible vision of glass. Each country has its vision of glass. It's made with the same techniques in Japan, Mexico, and Italy. The difference is what people put in it. How they make it relates to their cultural vision of the world.

I want [people] to enjoy the simple point of being in a garden, to smell the flowers and take a big breath before returning to reality.

PLWhy did you make your blown-glass bricks concave?

JMOIt results from one of those mistakes that I love. Had I just ordered some glass bricks, they would have been perfect. But because I was there, I saw that this concave construction made them more sensual. The natural pigments produce fluctuating colours, which generate a sense of vibration—a sensation I desire—when they are assembled.

PLDoes glass itself, the materials used to make it, and the colours it can convey play a symbolic role in your art-making? Your earliest works were made with sulphur, right?

JMOThe French word for sulphur (soufre) sounds like souffrir, which means to suffer, so it was very ambiguous. I love to play with words for titles.

Colour, of course, is important. The red beads are linked to blood, which was also symbolically important to my work at one point, and the blue is for the sea or the night. My palette is quite small because colouring glass can be very tricky.

For the mirrored beads, I use mirrored glass inside because it catches people; you enter into the piece and are trapped in it, which I love. That's why I reproduce the beads in metal for outside projects. The sculpture looks like glass, but it's not. And some pieces are mixed, so you don't see where the glass ends and the metal begins, like with Le Kiosque des Noctambules.

PLWhen did the glass beads first become metal beads and how did that change the potential outcomes of your artworks?

JMOI think it became important when I did the fountains in Doha. It's a big installation with 114 fountain sculptures outside. Because of the heat and extreme weather conditions, it wasn't possible to forge them in glass. I started to think about playing with the idea of illusion. I wanted to create the illusion of glass, but make them in metal.

When you don't know, you can imagine that the beaded sculptures in Doha are in black glass. In fact, they are in metal covered with ceramic. The material is so strong and I experimented in extreme conditions. Now I can even do things at the North Pole if I want.

PLThe fountain in Doha is almost like a garden. There are so many abstract root-like forms; they appear to sprout from the ground.

JMOI called the fountain sculptures ALFA (2019), which is the name of a desert grass. Sighted in front of the National Museum of Qatar, which was designed by Jean Nouvel, they look like grass. When you walk around the building, they look like different letters; different points of view provide different meanings for the installation.

The building is amazing. When you walk along the street, you see it through the fountain sculptures, which is like seeing the building through a forest.

PLWhen did you start shaping stainless-steel beads into floral forms?

JMOAbout seven years ago, when I had a show with Kukje Gallery in Seoul. I wanted to pay homage to the lotus, so I made my first series of lotus flowers, which are related to Asia and the idea of contemplation. It was also about confronting beauty, which is an important part of my work.

Flowers ... [are] like a key for connecting with art history, with history in general, because of the stories that lead you to their practical uses.

PLDo flowers have a poetic meaning for you?

JMOFlowers have been one of my passions since I was a child. But they're more than poetic—they're like a key for connecting with art history, with history in general, because of the stories that lead you to their practical uses, such as in medicine, which fascinates me.

Of course, I pay homage to the rose as the queen of flowers, but I also like simple flowers, like the wild ones you see along the road.

PLDuring your residency at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, you observed the flowers in the museum's artworks, right?

JMOYes, in the tapestries, ironwork, architecture, furnishings, and paintings. The Gardner Museum residency was very important to me. I made a treasure hunt of the collection to discover the secret meanings of paintings by looking at these flowers.

It's also where I designed the project for the gardens of Château de Versailles and found the idea of the connection between Louis XIV's dances and my work.

PLDid your residency at the Gardner Museum, and the book you made after being there, impact the flower sculptures you made for the gardens of the Petit Palais, Seoul's Imperial Palace Garden, or the Brooklyn Botanic Garden?

JMOYes. Peony, the Knot of Shame (2015)—the first big knot sculpture in the shape of a peony—was for the show at the Gardner. The peony was part of Isabella's collection, who was the first woman in the United States to be a landscape designer.

She had a degree and her own winter house to grow flowers. She was obsessed with flowers and had a big library about them. It was fascinating to look at all the amazing books she collected because she was able to buy anything she wanted. She had incredible books about plants and gardens.

PLThat research was then expanded at Versailles and the Petit Palais.

JMOVersailles was important because I was working with a landscape designer. I had to work in another way to adapt my sculpture to the garden. When you start from the beginning with a landscape designer, you can go in a very strong way. It wasn't just a sculpture in the middle of a garden—it was more about integrating it into the landscape.

The designer told me, you are playing the first act of the garden because the garden needs time. You start with the sculpture, but five years later the garden will have grown and the sculpture will be more discreet. The view of the sculpture changes as the garden grows around it.

PLWhat was the planning process for the Brooklyn Botanic Garden project?

JMOWe began by trying to find a garden in New York. My first thought was the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, because it is next to the Brooklyn Museum, where I had my survey show around ten years ago.

The Brooklyn Botanic Garden is a reconstruction of different gardens—the Japanese garden, the fragrance garden, and the lily pond, which has this amazing platform with such perfect reflections—and you are close to the sculpture's inspiration, the lilies.

For me, it was really perfect, and a way to reconnect with Anne Pasternak, Brooklyn Museum's director. We have wanted to do a project together for more than 20 years since she was the director at Creative Time. When I called her to ask if she could introduce me to someone at the BBG, she was thrilled.

PLHow does the Brooklyn Botanic Garden project differ from your outdoor installations at the Petit Palais or Seoul Museum of Art?

JMOEach garden is a different story. Because is it a reconstruction, the Brooklyn Botanic Garden is an educational garden, with different species and labels behind every tree and flower. It's a grand garden, which is why I created these pieces for this garden. It's quite big compared to the others; the Petit Palais was very small and the Korean garden was quite intimate.

We're always rushing in the big city. How do you impose a new rhythm to look at art? That's the challenge for sculptures today.

Paris was about an exotic garden from the 19th century with strange flowers. New species from around the world were shown during international exhibitions. The building was very important in terms of the Beaux-Arts style architecture of the time. It's an enclosed garden, which was designed to be a resting place while looking at the exhibitions.

In Seoul, it was in a historical place that had never shown contemporary art. Some pieces were in the museum and others in the garden. Their historical department had to be persuaded to have pieces in the garden, which has buildings dating back to the 17th century. I really loved the show there and learned a lot in relation to my passion for gardens. We had 500,000 visitors in three months.

PLWhat are the flowers that have inspired these garden artworks?

JMOThere are lotus flowers in the Japanese garden pond, water lilies for the lily pond, and roses for the fragrance garden. But at the end of the day, you can link them to abstract sculptures. What I love in this new series are the works in mirrored stainless steel. It's a new step for me in terms of size and monumentality. It's like the beginning and end of a story. It's also the cycle of life.

PLHow important is the placement of the pieces?

JMOThe placements are important in terms of building a story. I wanted to motivate visitors to move through the garden and walk around the sculptures to see how they change. Sometimes you have this feeling that the flower is blooming when you walk around it.

It's important for me to put people in the rhythm of a walk, to slow them down. We're always rushing in the big city. How do you impose a new rhythm to look at art? That's the challenge for sculptures today.

Through my work, I try to bring people back to reality. I want them to enjoy the simple point of being in a garden, to smell the flowers and take a big breath before returning to reality. I think it's one of the goals of my generation.

PLIn the big, mirrored pieces, the reflected patterns almost resemble tattoos. How does reflection affect how these sculptures are perceived?

JMOThe reflection gives you two different feelings. Because the sculpture reflects itself, it provides a smaller self-representation, like its own DNA. It also gives this idea of energy. The reflection is a way to catch the surrounding nature—the flight of a bird; your moving reflection; the colours and movement of trees. It makes the sculpture very lively.

I just experimented with a big bridge in a garden in France, built with stainless steel and polished, mirror beads. Up close, you are trapped by the sculpture. You are reflected thousands of times. But from a distance, it disappears, because it reflects the surrounding landscape. It's quite magical. It creates a pattern to discover.

PLIn what other ways do you work with flowers in your work?

JMOI paint them. I'm making a new series of large abstract flower paintings in colour for my fall show at Perrotin in New York (27 October–23 December 2023). I have made similar works for a show in Asia, but haven't shown these sorts of colour paintings in the U.S. or Paris.

I consider the flowers on canvas to be the sculptures' shadows. I showed a series of black flower paintings on silver-leaf-covered canvases at the Louvre in Paris in 2019. I love painting because it's a practice that I can do by myself.

PLHow do your garden installations differ from your fountains?

JMOThe gardens are different because they're temporary, so you can be a little more provocative. But when something is there to stay, you have to find a real connection with the history of the place and create a story that can be lived with for years.

Doing a show like The Flowers of Hypnosis is like a firework—you can do a very impressive thing. With public art, it has to be more subtle. I love working in both ways—to be wild with a project like this one, and to find a more intimate way to communicate with the community when doing a project in a public space. —[O]