Joselina Cruz

Joselina Cruz. Courtesy Museum of Contemporary Art and Design (MCAD) Manila, De La Salle College of Saint Benilde. Photo: MM Yu.

Joselina Cruz. Courtesy Museum of Contemporary Art and Design (MCAD) Manila, De La Salle College of Saint Benilde. Photo: MM Yu.

Since 2011, Joselina Cruz has been the director and curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design (MCAD), De La Salle-College of Saint Benilde, Manila, which is celebrating its tenth anniversary in 2018 with a series of programmes and special exhibitions, starting with Flatlands (7 December 2017–4 March 2018). A group show with James Beckett, Hrair Sarkissian, Amie Siegel and Eugenio Tibaldi, Flatlands applied the 'idea of flatness to the re-imagination of "peripheral" sites as points of origin rather than as geographies often marked as colonised territories.' It did so by looking at 'the efforts of decolonisation' through the study of various constructed environments, from 'India's Chandigarh, to the Neapolitan beaches of the town of Licola.'

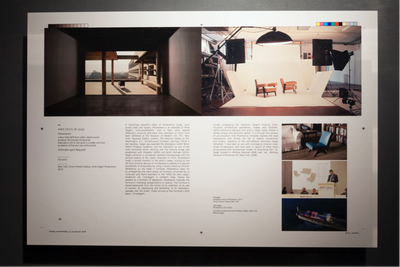

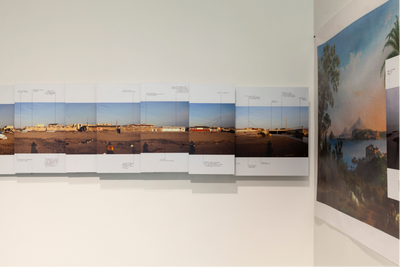

Flatlands started on the ground floor of the MCAD exhibition space, with James Beckett's installation, Negative Space: A Scenario Generator for Clandestine Building in Africa (2015), which includes a series of photographs depicting modernist architectures in Africa; Hrair Sarkissian's 'Istory' series (2010), composed of photographs from the interiors of libraries and archives in Istanbul; and Eugenio Tibaldi's project Seaside (2012), a panoramic installation of photographs documenting the Licola coastline of Naples, Italy, littered with the detritus of modern life, from trash to abandoned cars and illegal housing structures. Showing in the mezzanine gallery was Amie Siegel's film Provenance (2013), which charts the movement of furniture designed by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret for Chandigarh, one of India's first planned cities, to European collectors' homes—albeit in reverse. Shown alongside Provenance was Siegel's film documenting Provenance's Christie's auction, Lot 248 (2013).

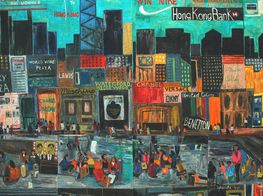

Another highlight of MCAD's tenth anniversary year is the exhibition Pacita Abad: A Million Things to Say (12 April–1 July 2018), co-curated by Cruz and Abad's nephew, artist Pio Abad. Pacita Abad was a prolific Philippine-American painter who started her career in Washington DC after turning down a full scholarship at the Berkeley School of Law in order to pursue art, enrolling at the Corcoran School of Art in 1976 where she was taught by Berthold Schmutzhart and Blaine Larson. Following her education at the Corcoran, Abad went to New York to study at the Art Students League under John Heliker and Robert Beverly Hale. The exhibition covers the breadth of Abad's prolific career, which saw her travels around the world—from Bangladesh to Cambodia, Papua New Guinea to Sudan—feed into her practice.

Aside from her work at MCAD, Cruz is an accomplished curator. Most recently, she curated The Spectre of Comparison, the standout Philippine Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale in 2017, which showed works by Lani Maestro and Manuel Ocampo. The Pavilion's title is taken from the 1887 novel Noli Me Tángere by writer (and Philippine national hero) José Rizal, who wrote it in Spanish when he was living in Berlin, under the title el demonio de las comparaciones. The Pavilion drew on the experience that Rizal narrated in the novel: of being unable to look at the Botanical Garden of Manila without remembering Europe's own gardens—a 'double-vision' that reflects what the curatorial statement described as the 'double-consciousness experienced by a colonial émigré of the 19th century.'

In 2009, Cruz was a 'networking curator' for the 13th Jakarta Biennale, and in 2008, she was co-curator of the 2nd Singapore Biennale alongside Matthew Ngui. Other recent exhibitions include Creative Index: An Exhibition in Manila for the 10th Regional Anniversary of the Nippon Foundation's Asian Public Intellectuals Fellowship programme in 2010. Prior to her role at MCAD, she worked as a curator for the Lopez Memorial Museum in Manila (2001–04) and the Singapore Art Museum (2004–07). During her time at MCAD, Cruz has worked on significant exhibitions, including a presentation of eight performance artists and their practices in Re-enactments (13 July–10 September 2017), featuring Francis Alÿs, Yason Banal, Erick Beltrán, Dora García, Liz Magic Laser, Michelle Lopez, Gabriella Mangano, and Silvana Mangano); and a major exhibition of some 20 works by Thai artist filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul, The Serenity of Madness (18 February–14 May 2017).

In this conversation, Cruz talks about her work with MCAD, and expands on the ideas behind her Venice Pavilion, concluding with thoughts on what she calls 'the local-regional-global trifecta' that she mediates in her practice.

SBLet's start with Pacita Abad's solo exhibition, which opened on 12 April. How did you and co-curator Pio Abad formulate and edit this particular show, and how did Pio Abad's personal relationship with Pacita influence your curatorial choices?

JCThe exhibition, which we've entitled Pacita Abad: A Million Things to Say, mostly looks at a technique that Pacita called trapunto painting. Trapunto is basically a quilting method, but what Pacita did was include other elements like painting, objects, stitching, and textiles into these works, and she also stuffed areas in her paintings that gave the works a certain dimensionality. The trapunto paintings are interesting because, for me, they epitomise Pacita Abad; it was this capacity to include many things in one work—she had a million things to say! And I think the trapunto technique gave her the possibility of working the subject matter, process and material into one object. A trapunto, if you look at it closely, is so detailed and its construction so precise—the back of a trapunto is a fascinating thing to see. But this precision almost disappears once we are confronted with the colour, design and material of the composition; the final image seduces us, and almost incapacitates us from a more discerning engagement.

My discussions with Pio early on was to re-examine Pacita's body of work. But it was also necessary to take a huge step away from it and recognise the fact that Pacita's public persona was largely influenced by her construction of self as a woman of colour, which can be read in several registers: primarily in terms of how colour informed her art, but also in the way she played up the colour of her skin, which implied concepts of indigeneity and the exotic. Pacita's life was far-reaching geographically, and her work reflects this.

Pio and I both agreed that it was important to reclaim the practice beyond the image. Working with Pio allowed for many insights into the work of Pacita, which gave the curatorial process an internal voice. But because Pio is also an artist, and a very critical one at that, he did tend to lean towards the works with a more political edge, like Pacita's social realist works, in our discussions and considerations of what was important to include in the exhibition.

In the end, we decided to veer away from these paintings and concentrate on works that reflect her travels, which are more personal and unique. These include abstract masks from Africa, an underwater series created after she learned how to scuba dive and went to dive spots around the Philippines, and abstract works from two different periods: when she experimented in the early 1990s building up non-figurative trapuntos, and when she started painting circles and dots during the late 1990s and 2000s, before she passed away in 2004. To round out the show, the entire mezzanine floor is dedicated to a timeline and resource centre where visitors can immerse themselves in understanding Pacita's practice.

These choices hopefully give the old formulations of Pacita—that of an exotic, crafty woman of colour—a different perspective for viewers of the 21st century, and provides a new appreciation for her generation. When Pacita had exhibitions in Manila, her work was quite different from the Filipino artists at the time, when painting and sculpture were key media for a generation identified by social realism. This was a sombre period, when 'serious' subject matter on current social events in the Philippines was popular, and by contrast Pacita's canvases were wild, colourful, and fit into the categories of mixed media, textile, and craft. I think she needs to be seen beyond the wildness of her canvases and her personality. There are very few articles or interviews on her that did not wax lyrical about how her large personality was equal to her colourful, wild and large canvasses.

SBPacita Abad's show follows on from Flatlands, which charted the way that international modernism and its relationship to nation-building evolved into a postmodern condition of formlessness, which is now being reversed with a return to nationalist thinking in the 21st century. It was fitting that the brutalist Cultural Center of the Philippines, designed by Leandro Locsin under the Marcos Regime, is but a stone's throw from MCAD; the building was somehow drawn into the show's frame of reference.

Could you expand on how this exhibition reflects MCAD's mission, as you have previously expressed, to connect Philippine contemporary art with 'a bigger conversation outside the country, even outside of Asia'?

JCI have always imagined MCAD as a place from which larger conversations could emanate from. Flatlands, for me, explored events that had already been brewing or had already taken place—where cities were being stretched out from supposed power centres, organically growing, their edges constantly in flux, and where power was almost always being contested. Perhaps Flatlands as an exhibition was less about Philippine contemporary art, but more about reflecting on the world and its events, curating from the context of the Philippines and how these works could sit comfortably within the site of MCAD.

You pointed out quite astutely that we are spitting distance from the CCP. Manila was part of the imagination of a failed utopia, as most modernist cities have become. The exhibition sought to present the context of its making, and its rejection. In Manila this was part of a dictator's vision for a country under Martial Law. The exhibition also looked at ideas of desire, power, and nostalgia with its equivalent meanings in the wider net of the market: desire finds itself satisfied through consumption, nostalgia a space where desire is complicit, and power is the currency we all work with. These discussions are all at play in the Philippines, and in Manila, especially with its art fairs, local auction houses and galleries. These manifest in the areas of politics and art.

SBReturning to MCAD's anniversary year, there are a number of projects planned, including the launch of the first anthology of writings by curator and author Marian Pastor Roces, founding director of MCAD, and founder and president of the sole museum development corporation in the Philippines, TAO Inc.

JCMarian Pastor Roces is one of the more brilliant minds and thinkers in Manila. She was at MCAD from the beginning, when the idea for MCAD was being developed, and then curated its first two shows before she left. I have great respect for Marian and I think it is high time that her works were collected into a volume. While we won't be able to reproduce everything, I think putting together something like 50 of her more important and salient essays will be an important contribution to the circulation of her ideas.

Marian wrote several essays critiquing the system of large-scale exhibitions, one of my favourites being 'Crystal Palace Exhibitions', which effectively critiqued biennales. Another essay I enjoy very much is 'Vexed Modernity', which was an exposition on the lack of scholarship surrounding the paintings of Juan Luna and Félix Resurección Hidalgo, Philippine painters from the 19th century, taking a hard look at how these artists have been formulated as cultural heroes and the process of how they've been mythologised in Philippine art history and culture.

SBOf the exhibitions you have staged during your time at MCAD, which have been the most important, challenging, meaningful or most effective when it comes to the mission of the gallery and college, your own curatorial position when it comes to locating Philippine art within a wider more global landscape, and the interaction and engagement from audiences?

JCThere are actually several, or perhaps all the shows I have worked at MCAD have been all those things you describe. I realise this can seem like a cop out, but I truly enjoy the process of putting together exhibitions, and each exhibition I have done has been unique and meaningful. MCAD is an evolving institution, and I think most institutions should be that way—something that grows and evolves, not necessarily changing skin, but adapting and responding as much as it can to what is happening in the global landscape. Each moment asks for what it needs, and as an institution with a responsibility to the public, we have to incline ourselves to that historical moment. This is not to say that our exhibitions have been reactive. I prefer to think that the exhibitions have been observant, and perhaps tried to divine what could be considered relevant in a future moment.

To talk about one example, Vexed Contemporary (26 August–21 November 2015) was the largest Filipino exhibition I put up at MCAD in terms of number, with 16 artists including Kawayan de Guia, Maria Taniguchi, Leslie de Chavez, and Pio Abad. The exhibition thought about the artistic practices of a specific generation that grew up with a different sense of martial law—some were children who grew up under Marcos; others were born after the Marcoses were exiled. Together they matured with the art world in Manila in the early 2000s as young artists who opened up independent art spaces and later integrated themselves with young galleries showing more contemporary works.

Vexed Contemporary was also a response to a frustration about how Philippine art practices at the time appeared to have been stunted locally. Most of the young Filipino artists who left art school in the mid- to late-1990s had the opportunity to travel and even study outside of the Philippines, which influenced their art production. While these artists were engaging critical spaces outside of the Philippines, conversing with a larger audience, speaking to exciting curators, exhibiting in important shows and producing important and challenging work, they had difficulty transposing this artistic language when they showed back here. I hoped that I could create a statement that we had artists actively negotiating their position and concerns between local and global art economies.

There was almost this resistance among the local art world in placing these artists within the imagination of what could be considered as art, and I was keen to bring their works together into one exhibition to make an argument that painting was not the only way contemporaneity in art could be expressed. Painting was and continues to be the predominant practice in the Philippines, with figurative social realism still prevalent and popular among artists and collectors.

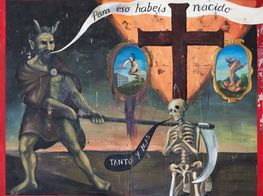

SBThe Philippine Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, which you curated, was a nuanced encounter between two very different artistic practices that were equally shaped by the impact of the Marcos regime. Philippine-Canadian Lani Maestro, who left the country at the height of the Marcos dictatorship, presented a series of neon signs, while Manuel Ocampo, who left the Philippines after the 1986 revolution, showed figurative canvases, which blend symbolisms of modern life with Christian and animist iconography.

Could you expand on the pairing of these two artists?

JCI'm really happy that you thought the show nuanced. I think this was important for me too—not to force the two artists to work together, but to keep true to their practices. What was more important was to flesh out the pertinent works that would respond well to each other, to the space, and to the platform of the Venice Biennale.

I could say that the conceptual starting point of the exhibition was Rizal's protagonist's utterance of that enigmatic phrase. But another starting point was two pieces by Lani Maestro: an installation where children disappear and reappear in alternating slide images as they float in an ocean, and A Voice Remembers Nothing (1994), which is the audio recording of a voice reading out the names of those who disappeared during the Marcos regime. These were incredibly violent images and got me thinking about Manuel's canvasses, which were just as violent. Both practices deal with violence brought on by cruel occupations and removal of freedoms, but in a very different manner. This struck me as quite unique, and I imagined how powerful their works would be once they confronted each other in the same space. The levels of tension across the works are multi-dimensional. Maestro's violence on the body through language is so palpable that I see these as a minimalist and conceptual response to Ocampo's canvasses of mutilated images and vice-versa.

However, I also wanted to comment that these practices that responded to the politics in the Philippines were produced elsewhere. I am always fascinated by these dis-locations and Rizal's double-consciousness was for me so on point as a device to unravel and link the two practices, but also to have the exhibition set against the backdrop of history and literature.

SBHow did your curatorial choices respond to this being a national pavilion when thinking about the state of the nation today, both in terms of the Philippines itself, and the resurgence of nationalist thinking worldwide?

JCThere definitely was something there, but it is interesting that the pavilion's exhibition could be read as a return to ideas of the nation. This of course is due to Rizal living during that time in the 19th century, but also during that moment when the Philippines was fighting to become independent of the Spaniards, and form the idea of the 'Filipino', which up to that point was not linked to a nation, but to the formation of one. It was the only way to gain independence: to 'retreat' into the production of a nation, which must have been progressive thinking during that time. There was very little choice for colonised places if they wanted to gain independence except to become a nation.

But the exhibition was hardly that—it was the sentiment of the doubling image that created that space which we could occupy, produce and engage with criticality. Armed with the ability to compare—to imagine from space to space—is a privilege, and there are certain historical moments that need to be responded to. When artists such as Maestro and Ocampo are able to do this, these moments can mark the narratives of Philippine histories.

SBWhen thinking about the different institutions and landscapes that your work as a curator takes you—even in terms of your education first at the University of the Philippines, and then at the Royal College of Art, London—what is your personal perspective of the developing landscape of contemporary art as it mediates local, regional, and global concerns?

JCMy work as a curator has always functioned as a way to think about the world and how ideas can be navigated across contexts. This became especially crucial when I returned to the Philippines and worked at MCAD, a local institution that could engage with conditions of the global through the production of exhibitions and working with artists. MCAD is not simply a space that receives or makes exhibitions thoughtlessly. Exhibition-making is as important a practice as curation. Curation perceives exhibitions: it does the research, teases out possibilities and tests ideas internally—it is almost a neurosis whereby you knock about in your head all the possibilities of how an exhibition could turn out. I think exhibition-making involves the actual production, where the deep work with the artist happens. If this involves a commission, the work is negotiated, and for existing works a conversation takes place around their contextualisation as part of the show and the larger context of the exhibition space. This entire process is the point at which the local, regional, and global have serious encounters, and conversations emerge.

Curating across cultures, generations and histories produces sensitive tensions, which as curators we have to be mindful of. We can have many ideas under one umbrella of an exhibition, but still produce flimsy art history, if any at all. For me, curating continues to be a spatial practice, whether this manifests as a publication, on a social media feed, or in a physical site: space can be many things, and the spaces we produce exhibitions in, even the works of art we make when collaborating with artists, dictate how ideas travel. The local, regional and global trifecta need to be recognised as having different configurations without any hierarchies, allowing for a much more unbiased exchanges. These conversations are crucial because it allows ideas to flow across contexts, creating diverse experiences and forming new audiences. I'm always grateful when an exhibition, in its entirety, is able to speak across different knowledges without becoming didactic.

The exhibitions I curate at MCAD have as their primary audience people who live in Manila—artists, students, writers, critics, historians, academia; locus points of discovery, possibilities and difference but also of recognition and reflection. I would like to indulge in the thought that the exhibitions I curate are spaces that invite these moments, but at the same time lend themselves to criticality and self-reflexivity. Contemporary art, however, circulates in ways that these exhibitions do not remain on the level of the local—not only because I work with international artists—but within the ecology of contemporary art discourses from every other elsewhere. Locking on these points is like connecting the dots across constellations, or within a constellation.

For me, it becomes uninteresting, if not unfair, when so many works are lumped in one site under an exhibition setting. These do not produce thoughtful spaces. Biennales, despite me having been part of several, are problematic sites—we know this. In the same way that art fairs are not spaces to see art, but places to see the spectacle of the market and to meet people who make the art world turn. I can sometimes see a work or two that pique my interest, but I have to experience these works elsewhere in an exhibition, or even in the artists' studio, to understand their 'place'.

As curators, we also have to be mindful of where we are. We have to acknowledge that we are located somewhere, despite Instagram and Facebook suggesting otherwise. Geography plays a powerful role in exhibition-making and it is this acknowledgment that prods us to think about and make exhibitions that enable us to present the complexity of contemporary art with sympathy and care. —[O]