Maria Taniguchi

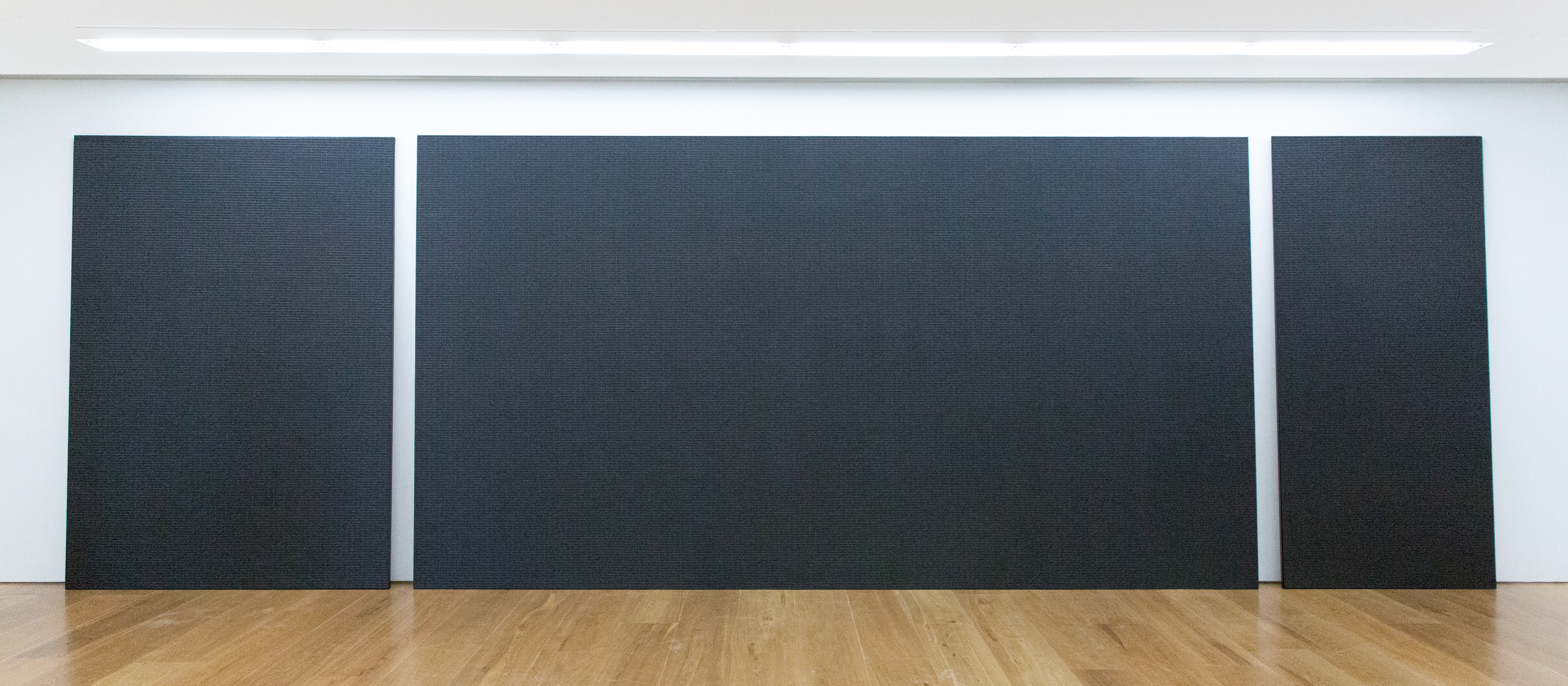

Maria Taniguchi. Image courtesy Galerie Perrotin. Photo: Ringo Cheung.

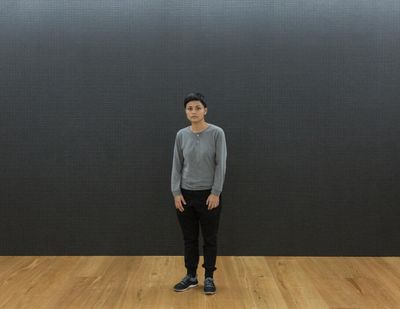

Maria Taniguchi. Image courtesy Galerie Perrotin. Photo: Ringo Cheung.

Preparing to sit down for my interview with Filipina artist, Maria Taniguchi, a small printed essay by Susan Gibb catches my eye on the coffee table in Galerie Perrotin's office.

Titled 'Dogs in Space, Witches of Dumaguete'1, the essay, referencing the artist's hometown of Dumaguete City and included in the catalogue for a recent exhibition featuring the artist's work at the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, seems a fitting reference to the artist. The pint sized Taniguchi is an alchemist herself. She transforms the mundane—bricks, pipes, clay—elevating them into objects loaded with symbolic and talismanic meaning. She turns the intangible into solid objects for contemplation and interaction. She captures time with the stroke of a paintbrush. Taniguchi's work is about the process and transformation of objects, exploring the moments in between and before.

Born into a family of sculptors Taniguchi also pursued sculpture, completing a BFA in sculpture at the University of the Philippines, and then continuing on in London, earning her MFA at Goldsmiths in 2009. Soon after, she resettled in Manila where she still practises. Today Taniguchi has expanded her practice to embrace painting, video and printmaking. These have earned her international recognition, culminating in her being awarded the Hugo Boss Asia Art Award for Emerging Asian Artists in 2015.

I have this future install in my head. It's kind of like a graph. I imagine the brick paintings all together forming this giant textual field, maybe like a code or graph. And they're all in space with their various vibrations. But mainly, because it's such a physical act, it takes a lot of time and effort.

In 2008 the artist started work on the brick paintings which were to become her signature, starting with canvases of 1.4 × 3 metres, before steadily increasing them in size to as large as 3 x 5.5 metres. The brick paintings—a grid of hundreds to thousands of small hand-painted black rectangular bricks—have become part of her daily practice, a ritualistic meditative marker of time, like slow rhythmic breaths, or the steady drip of water on stone.

Taniguchi works on the canvases with discipline and commitment, day in day out. She has painted hundreds so far. The paintings, as well as the installations, sculptures and video works she creates around them, are part of a larger whole, an organism. 'The brick paintings are one big work that comes in many small parts, like when you're downloading something from the Internet and it streams down in little pieces', the artist stated. The exhibited works in Galerie Perrotin—an installation or tubes and pipes that mimics a filtration system, and five towering black canvases—feed into one another, symbols and ruminations on the passing of time.

Taniguchi's work isn't about the end result, the work as object. Rather it is the time, effort and labour that goes into the works—both as an artist and as a viewer engaging with the works—that is valued. There is no drama, no grandiose statement. They are quiet works allowing for contemplation, physical objects through which the artist and viewer confront the self and slowly attain an awareness of the continuation, and distillation, of time through the matrix she has created.

DAThis essay, 'Dogs in Space, Witches of Dumaguete', just caught my eye. I find the anthropological history of witchcraft fascinating.

MTReally? This is an essay written by Susan Gibb for an ICA Singapore exhibition I did earlier this year [Sriwhana Spong and Maria Taniguchi: Oceanic feeling, 20 August–16 October 2016]. But it's so funny. My mum did a literature MA and her thesis was on witchcraft in Siquijor—which is an island of the Philippines known for witches and magic. If you're standing at the boulevard at Dumaguete, where I was born, you can see Siquijor just across the water. So she stayed there and did some research and compiled some stories. It was very interesting.

DADid you weave these stories and mythologies into your work too?

MTI didn't. I always like to talk about my work in neutral terms, but I guess there are some things underneath the brick matrix.

When I make the brick paintings I listen to a lot of novels—a lot of fiction, mostly. So I guess there's definitely text behind my work.

DAYou've made a lot of these wall paintings. They're quite repetitive and physical. Is this a meditative Zen process for you? Or is it more a confrontation with the self?

MTIt's a confrontation. I think it's quite violent. For me it's not Zen. Zen is when you empty your mind or you're trying to get into this extreme space. When I'm working on them I like to multitask. I like to do my reading. The paintings take up a lot of time; I'm constantly lining things, filling each brick in. It's a lot of focus. But then I put my headphones on, and I listen to everything and do half research and half listening to fiction.

DATell me a little more about your process? Do you have a particular ritual or system for painting the brick works?

MTThe way I paint, is on the floor; there's a layer of grey and then the brick matrix is drawn on with pencil. I go from one end to the other. Painting out like a printer, row by row. I don't have a set amount of bricks I need to print during the day. Sometimes it's a struggle to get into it, and I finish only a tiny bit.

All materials have frequencies, and for me that's why I'm so attracted to working with sculpture and objects. Obviously all of us are obsessed with objects in our everyday life, but I want to go a little bit further into this abstract field in terms of material.

Other times I finish a giant section. And this creates a kind of pattern on the surface, especially in natural light that makes it have a different surface in different light. Some of the brick paintings are more transparent than others—in particularly the pieces in the ICA show. There's a translucent effect with the black. If you put them in a room filled with natural light you see more discrepancies in the brick-making patterns. This registers the sections of bricks that I've worked on, on certain days.

DAA record of time?

MTYes, it's there. But it's really part of the surface and process of the making.

DAIt seems to require a lot of discipline, to do this day in day out.

MT[Laughs] Ummm, yeah maybe.

DAYou came from a sculpture background and it's interesting to note that despite the fact that the brick works are flat canvases, there's also a sculptural, or perhaps architectural, quality in the way they are displayed and the physical space they take up. The scale of the works is quote large and you lean them against the wall. Was this deliberate, having this continuity and linearity in your work from your sculptural practice?

MTWell, I kind of see the brick paintings as place-holders for imaginary space. But I've come to this point in my relationship with the brick paintings. Eight years ago when I started to do them, the concern was much more about the surface, skin, or cladding, and I was exploring patterns. It was about looking at the surface. Then eventually over a period of time my relationship with the brick paintings became a little bit more complicated.

I feel like I started to conflate system and structure and process with making the surface something more organic. So it conflated itself with the practice overall; it's a body of work that has started to take root like a nervous system within a larger practice. Alongside the brick paintings, all the other works are reflection, or refractions; they're kinda like the brick paintings but in other forms, at least in my head.

DASo they're all part of a larger organism?

MTYes, exactly!

DAIn one interview you said the brick paintings are one big work that comes in many small parts. Where do you envisage this will end? How will you know that you've reached the whole?

MTI have this future install in my head. It's kind of like a graph. I imagine the brick paintings all together forming this giant textual field, maybe like a code or graph. And they're all in space with their various vibrations. But mainly, because it's such a physical act, it takes a lot of time and effort, and practically speaking I was very busy last year. I'm not sure how long I can sustain a practice that needs a large space and a lot of time to do. I'm also a pretty distracted person. I have so many other things I want to do; the other work alongside the brick paintings also has its own exploration to do.

Next year I'm going to revisit a work I did in 2012 called Figure Study. (I often reuse titles, so it can be a little confusing.) It's a sculptural work that happens to have a video in it—that was my first figure study. It's of guys digging. There's a monitor with a black and white video of two men set in a jungle and they're digging for something, although we don't know what they're digging for. And I kind of saw it as a scale ... the video is on one end and on the other end of the floor there's a slab of clay that is like an after image. You know when you look at an image and then you look away, afterwards there's an imprint of it still in your mind. So the red clay slab, made of fired terracotta, was for me a reflection, an after image from the monitor.

Also it's about things moving around, things becoming, transforming from one material to another but still being part of the same logic. So, I'm going back to this work. And then working on ceramic work next year. My mum and I are building a kiln in Dumaguete, which Susan refers to in the witch essay. I keep referring to this because she keeps referring to it in her essay. So I'm going back to Negros island—incidentally where the figure study was filmed—and I'll see what I can do.

DASo, it's a study of work about work. But in this context it's also a work about alchemy, about transformation, particularly with clay: Being turned from earth into an artistic object we ascribe cultural value to.

MTYes, and it's also about a psychic charge to a material. All materials have frequencies, and for me that's why I'm so attracted to working with sculpture and objects. Obviously all of us are obsessed with objects in our everyday life, but I want to go a little bit further into this abstract field in terms of material.

DAI like what you once said about marble, how you liked its energy and touch. The tactility of objects is something we often take for granted. Materials just have a utilitarian value. But you look beyond that.

MTRight. I think people are too obsessed with veneers. Like marble veneer or wood veneer. It's just for show.

Yes. In the beginning in the process of making my brick paintings I thought about that, and what a strange thing a veneer really is. It's mundane, it's everyday, but it can also be something that is light and totally abstract as a material.

DACan you tell me a little about the fountain installation in the exhibition. It looks like a mini irrigation system with tubes and a pipe leading to a small glass pool.

MTI see it more like ... I know it's a sculpture, but I see it more like a drawing. It is like lines and masses in space for me. That's why it was so important for the material to be transparent. There are obvious things regarding circulation and repetition that are a throwback to the brick paintings.

When I'm working on [my paintings] I like to multitask. I like to do my reading. The paintings take up a lot of time; I'm constantly lining things, filling each brick in. It's a lot of focus. But then I put my headphones on, and I listen to everything and do half research and half listening to fiction.

It is modeled on an irrigation system. I'm working on a commission for the Jorge B. Vargas Museum in Manila. The curator, Patrick Flores, asked me to work around a specific site. The site is the Balara Filtration Plant and this is a filtration complex that was put in place in 1938 and half the water of Manila flows through it. It starts from the mountain range and goes into a big dam, then a smaller dam and then through the city. It goes through this filtration complex that looks like a park with lots of little machines and lots of underground pipes circulating and cleaning all this water, which is eventually delivered to 10 million people. It processes 600 million litres a day.

Anyway, I've been thinking a lot about this project. I even wrote a short story about it. At the same time that Patrick asked me to work on this for a show next year, Singaporean artist Heman Chong asked me to contribute that short story to a book he's making. It will be out next year.

The story only mentions my work obliquely. I wanted to weave this logic of practice into the story while the character is walking around the complex looking at these structures.

DAWhat are you currently working on?

MTWe made a proposal for the Venice Biennale—the Philippine Pavilion is an open call. We had a fictional proposal, something to do with Imelda Marcos' jewellery. It's probably more up Pio's alley [Pio Abad]. We like to do things together, things that don't quite fit into our own individual practices but that work as a collaboration.

There are a few things shaping up for next year. I'm interested in doing smaller projects. I'm aggressively pursuing 'Things That Can Happen', a non-profit art space in Hong Kong. —[O]

1 Susan Gibb, 'Dogs in Space, Witches of Dumaguete', catalogue essay for Sriwhana Spong and Maria Taniguchi: Oceanic feeling (20 August—16 October 2016, Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore).