Jude Rae on Thinking through Visual Experience

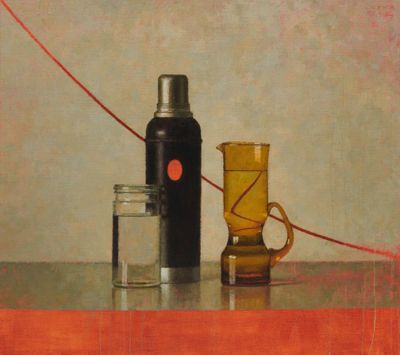

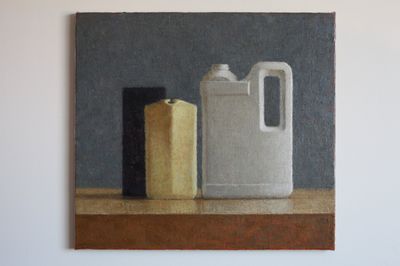

Jude Rae. Courtesy Maria Stoljar, Talking with Painters.

Jude Rae. Courtesy Maria Stoljar, Talking with Painters.

In 2013, the well-known Australian painter Jude Rae made a series of three linked video works. She recalls that someone described them as a lesson in how to look at her paintings.

Like her paintings, these video works have a narrow depth of field and feature objects placed on a table. The camera goes in and out of focus, bringing a softness to the composition. The artist remarks that what she likes about the video medium is that it can be used to slow vision down and encourage contemplation.

Despite this momentary foray into video, over the last 30 years, Rae has remained committed to painting, interested in the medium's formal qualities and how they can be employed to examine how we look and see.

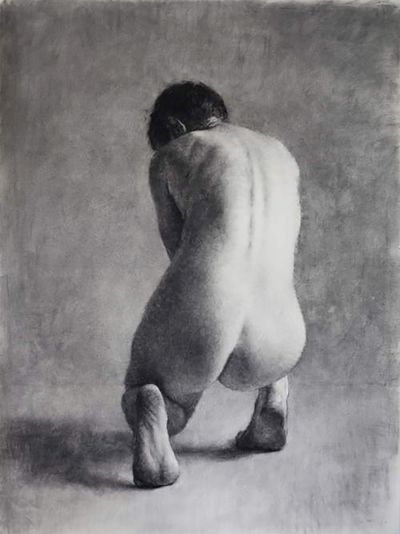

Having taught drawing for many years—most recently at the National Art School in Sydney—Rae is acutely aware of the challenges of representing our experience of three-dimensional space in two dimensions. For her, however, drawing and painting offer more complex and interesting ends than mere 'copying' or 'mimicry'. She describes her approach to both as 'thinking/ feeling through visual experience rather than representing it'.

Rae's latest exhibition 476-482 (24 August–30 September 2023) at Two Rooms in Tāmaki Makaurau / Auckland is a coming home of sorts. Now based in Sydney, Rae spent almost a decade living in Aotearoa New Zealand. Over this period, she served as director of South Island Art Projects (precursor to The Physics Room), an experimental, project-based initiative in Ōtautahi / Christchurch, described by art historian Christina Barton as importantly radical under Rae's stewardship, and an unusual sideline for a representational painter, which reflects the conceptual nature of her practice.

Rae talks of the influence the time in New Zealand had upon her work, introducing her to modernists such as Gordon Walters and Colin McCahon, and most importantly allowing her the time and space to find her own approach away from the Australian scene.

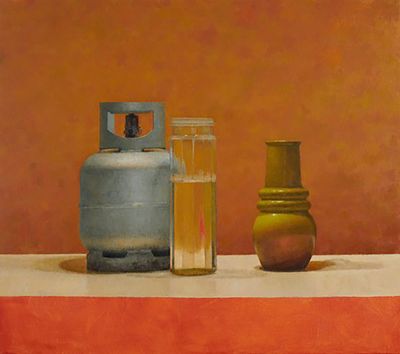

The show in Auckland features seven small, square oil paintings evenly positioned at eye height along one wall. Each work depicts one or two objects presented on a table, yet while they might trigger associations with an art historical trajectory of vanitas painting flowing back to the Dutch Masters, Rae is not interested in the symbolist or narrative associations that traditionally attach to still-life compositions. To deflect such interpretive associations, she started numbering her paintings in the late 1990s, and the works in this show are titled accordingly.

Rae's work traverses the blurred boundary between abstraction and representation. The items—a golden-black Bakelite bowl, cubes, Japanese cloth, a cream jar—are quotidian and unremarkable things, picked up in second-hand shops or found lying around. Rae explains she is drawn to the challenge their contours pose for her realist approach and equally for their abstract qualities which she can bring to the fore.

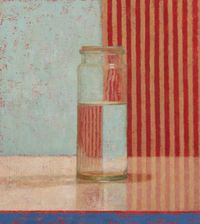

Each work presents acutely observed visual information distilled through geometrical shapes, lines, and carefully coordinated colours. In SL477 (2023), for example, a glass preserving jar filled with water features the naturally occurring reversal of refraction, while a piece of red and cream striped cloth is used to reinforce certain formal aspects of the compositions.

Yet the work never tips completely into the pool of abstraction, tethered to the limits of what exists before Rae in her studio, mediated by light and other atmospheric and spatial possibilities. Looking closely at the lines created by the cloth in SL478, one can see a hum of gold, reminiscent of evening light, that glances off the golden interior of a Bakelite bowl.

Rae juxtaposes the illusion of three-dimensional objects and space with the two-dimensional reality of the medium. In the exquisite SL481 (2023), a purple oblong box and creamy white cylindrical jar are perfectly modelled by layered dabs of paint drawing attention to the effects of light emanating from a single source, yet the turquoise background gives way to allow the red underpainting to surface. Another reminder of a painting's construction exists on the edge of each of the unframed works, where the raw canvas is visible. Here, a trim of white primer and drips of colour are allowed to coalesce.

In this interview, which took place as Rae's show opened in Auckland, the artist discusses the duality in her work, at one point holding her hand out and pinching her thumb and forefinger together, remarking on the extraordinary phenomenon of human consciousness, of the experience of being both object and subject. It is her hope that her subtle painterly interventions trigger curiosity in viewers to think over how they inhabit and see the world.

ADYour father was a painter and you learned to paint in a very traditional style from the age of 12. Could you speak about his influence?

JRThat's right. I grew up watching my father paint and began formal education in drawing and painting in my early teens. My father didn't exhibit his work very much; while it was important to him for people to see his work, I think he found the idea of exhibiting difficult.

Some artists are very sensitive to judgement, and back then certain aspects of the art world environment in Australia were not particularly friendly to representational painting. He was creating a kind of representational painting at a time when it seemed to be becoming irrelevant in contemporary art circles.

ADYou talk of representational painting becoming unfashionable during your father's time, but the art world has recently really embraced representational painting. How do you feel about that?

JR[Laughs] I say, welcome back!

ADDespite your father being a painter, and you learning to paint very early, you didn't initially pursue a career as an artist. Why?

JRI wasn't sure what to do with myself in my early twenties, and a career in painting seemed unlikely if not impossible. Instead, I studied for an arts degree at Sydney University. I enrolled in English language and literature—I loved poetry.

I was in a fairly messy emotional state and lost confidence, discontinuing my English Literature studies twice consecutively, which prevented me from re-enrolling in that department. Seeing the university counsellor was not so normal back then and never occurred to me. And that history led me by default to painting. I am glad it worked out like that.

ADYou did eventually complete a degree in Fine Arts (History) at the University of Sydney. Do you think that coming to painting initially via other disciplines impacted you?

JRYes, I think it made me more analytical. But what really influenced me was my husband and I moving to live in New Zealand.

ADIn what way did the move to New Zealand influence you?

JRNew Zealand gave me distance and helped me get some perspective on my roots.

Despite a brief revival of interest in representational painting in the mid-1980s, painting in general was becoming increasingly unfashionable when I was starting out in Sydney. Nevertheless, and perhaps naively, I could not believe that the sensitivity my father brought to figurative and representational painting would not be valued in the contemporary art environment.

Coming to New Zealand presented me with a different approach to Modernism, one more related to the English approach. I was aware of English painters like Ben Nicholson, his father William Nicholson, and Paul Nash. Something about the way Nash constructs his paintings and uses underlayers really impressed me. There's a directness to his work, no fuss. I don't think you would recognise his influence in my work, but his work had an impact.

In New Zealand, there was also an approach to geometric abstraction that I felt more in tune with for some reason. Painters like Walters and McCahon really resonated with me.

ADHow do you define your work's relationship with abstraction?

JRI am interested in negotiating the relationship between the traditions of representational painting and Abstraction in my work, but I don't really believe the distinction holds because all painting is 'abstract'. And as Morandi is supposed to have said 'there is nothing more abstract than reality.'

I have always been very sensitive to the emotional effects of light, not just in painting.

The older I get, the less I trust my eyes and the more I think I understand this remark. Morandi's paintings are refined meditations on the tension between two established traditions in Western art—representation and Abstraction. He employs every trick in the book to play off the tensions between painting as illusion and object. False attachment, perspectival distortion, and painterly materiality sit in wonderful balance with acute observation, formal balance, and tone/colour relationships. He is the ultimate painter's painter.

ADFrench philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty's writing also influenced your practice. Why did his work appeal to you?

JRYes, his writing was a big influence and continues to be a reference point for me. I don't pretend to understand the complexities of his philosophical tomes but essays such as 'Cézanne's Doubt' [1945] and transcripts of lectures broadcast on public radio are quite accessible.

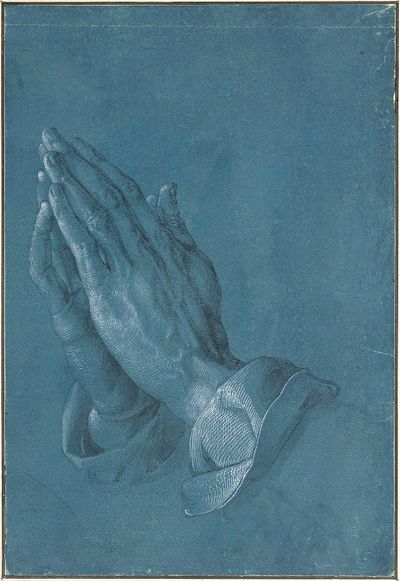

It is significant that the work of artists influenced his thinking. At one point, he refers to Albrecht Dürer's famous drawing of hands at prayer in the collection of the Albertina [Museum] to illustrate the mysterious fact that we are subject and object both—we are immersed in the world, and yet this connectedness often eludes us.

The challenge to Descartes' dualism suggests that the Cartesian split—that I am here and separate from objects and the rest of the world—is a useful but essentially false dichotomy. Merleau-Ponty was interested in how the work of certain artists helped him think about how we inhabit the world.

While I was at Sydney University, I enrolled in a first-year philosophy course, which included a unit on the history and philosophy of science. At some point, I encountered the phrase 'the theory laden-ness of observation', which seemed to hit me between the eyes.

Anyone who has attempted to draw knows that one of the problems with say, something like foreshortening, is that you see what you expect to see. A simple example of this is legs. Everyone knows that legs are long, but the angle of observation can compress the shapes we see. We struggle with foreshortening because we draw what we know rather than what we see. In this sense, learning classical objective drawing can be thought of as a template for critical thinking because it pushes us to reflect on our assumptions.

ADThat reminds me of an article I read recently on this neurological state of synaesthesia, a rare condition that causes the senses to intertwine, so you hear music but see shapes, or hear a name and see colour.

JRSynaesthesia is interesting for what it might teach us about our relationship to 'normal' vision, which can be very perfunctory and instrumental. I think most artists approach vision as much more complex than normally assumed and involving elements of other senses.

It's important to me that people see my work first-hand because it engages tactile elements and aspects that relate to depth of perception, which can't necessarily be seen on screen, and which articulate certain ambiguities. I think of these characteristics as small flags that complicate how someone might digest them.

Most of the time, we use our vision simply to navigate the world. Painting can slow this process in ways that anyone can apprehend if they take the time. It is important to me that people who don't know a lot about art still feel a pull towards my paintings.

ADIn a profile for Art Collector magazine, Justin Paton described your work as follows: 'Though the works don't trade in obvious political content, doubt is where their currency lies. They remind us not to rush into judgment but to hold fire and open our eyes.'

JR[Laughs]. Oh, he's very good. I remember reading that and thinking, 'You angel'. I think that he is referring to the doubt, the ambiguity that is generated in viewers.

I am not as interested in the psychological responses that my work might evoke as I am in this ambiguity. I am also interested in generating something that holds the attention. If there is strength in my work, then perhaps it is this.

ADYou sometimes refer to your paintings as object paintings, rather than still lifes. Why?

JRArt cannot escape its history—it is there whether we like it or not. Painting carries an enormous historical weight, and I am very aware of the genres and traditions. I am not as interested in the aspects of symbolism associated with the genre of still life as I am in the formal strengths of the genre, and its association with the beginnings of Modernism and Abstraction.

ADYou have worked in other mediums, such as video in 2013. Could you tell us about these works?

JRWell, I am not a video artist, but I have an enduring interest in certain approaches to video art, as distinct from cinema. In 2013, I made a series of three linked videos that I recall someone saw and described as 'lessons in how to look at my paintings'.

The approach is very simple. The reference point is still life and the camera is stationary. A very narrow depth of field travels across a table top and a series of objects come slowly in and out of focus. I wanted it to feel both dreamlike and concrete.

ADMaybe the person who commented on them was referring to the idea of contemplation.

JRYes, maybe that's what I like best about 'duration' in video—it slows you down.

ADCan you discuss your use of colour?

JRThe colours in these recent paintings are stronger perhaps. I have also used some different backdrops. In some of the paintings, I used a striped piece of Japanese cloth that provided opportunities for me to develop certain formal solutions.

Refractions and reflections also offer up the opportunities I am often looking for—say, for instance, a vertical to counter the strong horizontal of the table top. I enjoy finding formal solutions while working within the limitations of the studio.

Our relationship to colour fascinates me. I remember my mother saying that colours intensified for her as she got older but maybe you just notice such things more as you age. The relationship between colour and tone is endlessly interesting. I have always been very sensitive to the emotional effects of light, and not just in painting.

ADYour portrait of your mother [Portrait of the Artist's Mother - Val at 93 (2018)], is very beautiful.

JRThank you—I think that it might be my best portrait so far. In her last couple of years, she developed a mild form of dementia that caused her to gradually recede, and I found it was easier to paint her as a result.

In the painting I wanted the background to appear slightly luminous, as though she was moving into a place of light. Although she was a lapsed Catholic, she never really stopped being Catholic.

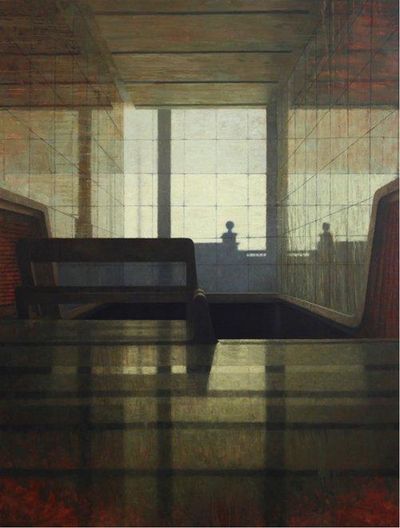

ADYou discussed light briefly before and reflection and refraction, which made me think of some of your large interior works.

JRThe studio and painting interiors are important to me—they are finite spaces. I love being outdoors, for instance, walking in cities or in the bush, but ultimately, I like to come back and be in an enclosed space.

In 'The Shock of the New' [BBC documentary series], Robert Hughes rather archly describes Henri Matisse as 'the painter of the great indoors'. I need a feeling of quiet in the studio, perhaps a sense of control—of light, of distractions—in order to immerse myself in painting and a quieting of the senses.

ADWhat do you do when you struggle with a painting?

JRWhen I had a garden in Canberra, I used to go out and pull weeds. I am a lot calmer now, and I don't have a garden anymore. Sometimes, I just turn the canvas around, so the painting faces the wall and I leave it alone for a while.

I really fought with SL476. It depicts an object that I haven't painted before, a Bakelite bowl with a scuffed faux gold interior given to me by someone a long time ago. The proportions are subtle and difficult, but I enjoy that struggle. It's partially why I stuck with painting gas bottles for so long—those subtle curves.

To some extent, my paintings are realistic but they are also inventions.

When a painting isn't quite working, it's like having a stone in your shoe. But I know a painting is almost finished when it has become more interesting than the object I am appearing to paint.

ADWhat most challenges you when painting?

JRIt's knowing I need to get somewhere with the painting, but not knowing where until I get there—and sometimes I don't. If a painting isn't working, it's unpleasant but often you just can't leave it alone, so you keep on banging away at it.

For me, representation in painting is more a question of finding a sense of presence and equivalence, rather than chasing verisimilitude.

People sometimes mistakenly assume that a certain quietness in my work suggests that I am a calm sort of person. Although it can be rewarding, it is not calming trying to get a painting to where I want it to be. Matisse once described the process of making a painting as being like a drunk kicking a door down. It's eloquent, isn't it?

I've come to realise that there is a strong imaginative element to realist painting. My paintings might look realistic, but they are also inventions. Writer Hilary Mantel talked about the relationship between truth and imagination in her 2017 BBC Reith Lectures. She described truth as 'an unruly beast'.

I used to think that because I was a realist painter, I didn't have much imagination. But it's an imaginative act just to get something on the canvas. —[O]