Moi Tran: 'Knowledge in marginalised spaces is not static'

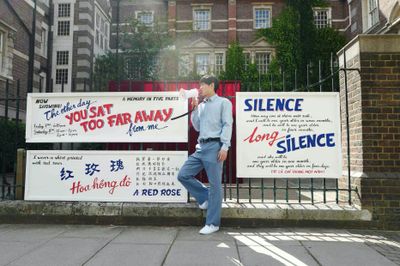

Moi Tran. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Yiannis Katsari.

Moi Tran. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Yiannis Katsari.

Moi Tran's multidisciplinary practice draws on her experience as an ethnic Chinese Northern Vietnamese migrant who fled persecution in the aftermath of the Vietnam/American war of the 1970s.

Tran's personal history is a consequence of one of Southeast Asia's most traumatic conflicts, and the experience of fleeing a previously colonised country to live in the U.K., a country of colonisers, left its mark. Becoming increasingly aware of the diaspora community around her, Tran experimented as an artist and researcher, reflecting on the concepts of life, death, movement, and migration—themes that recur in her prolific artistic practice.

In recent years, Tran's work has evolved through collaborations with community voices and and examinations of emotional vocabularies. The Other Day You Sat Too Far Away From Me / A Memory in Five Parts, presented at the Henry Moore Courtyard in London in 2018, was conceptualised as a ritualistic lament on Tran's father's death.

Chinese, Vietnamese, and Polish performers recited texts penned by the artist in their respective languages, while engaging in various acts, including sitting, lying down, and bicycle-riding. Tran refers to the resultant polyphony as signifying a 'form of resistance against the impositions of a dominant language.'

More recently, Tran co-curated the community-centred performance arts festival Encounter Bow with Chisenhale Dance, held in London's Bow district in June 2021, and presented a solo exhibition at Yeo Workshop, Singapore (I Love a Broad Margin to My Life, 10 May–3 July 2021), which included more than ten artworks and installations.

Among them was The Importance of Futile Task – the Puzzle (2018), originally presented as a collective performance in 2017 at the Chelsea School of Art's MAFA gallery. Composed of 2,000 identical-looking blank, black puzzle pieces with no other discerning features, the puzzle presented a seemingly impossible task.

Hand-painted canvas belts pinned to the exhibition's wall formed Boundaries, a grid of ten squares, and Possibilities of Things (both 2018), anchored in different places by wood blocks. Viewers could play with the configuration of these belts by changing the position of pins or weights. A commentary on demarcation and the resistance to it, the transportation of these pieces—they come in sealed envelopes—alludes to migratory paths.

With few exceptions, Moi Tran's works tend to be portable or movable. When Tran and her family moved to the U.K., they could only take a few belongings with them, things they could carry easily.

Tran's Yeo Workshop exhibition title was inspired by the eponymous 2011 memoir by Maxine Hong Kingston, itself inspired by a quote from Henry David Thoreau's Walden; or, Life in the Woods (1854). The mutations of meaning, from Thoreau's margin of leisure to Kingston's act of literary appropriation to Tran's invocation of the diasporic reality she shares with the Chinese-American novelist, signals the continual adaptations and accommodations, corporeal and cultural, that are often shared by migrant cultures.

This October, Tran will present a commissioned site-specific performance for SPILL Festival, which will journey to multiple locations in Ipswich, England (27–31 October 2021). The work is conceived as a continuation of Shy God – A Community Chorus, which takes its title from the legend of the Hoàn Kiếm Lake Turtle God in Vietnamese Folklore.

Shy God – A Community Chorus invites approximately 20 people across community groups and languages to create an unruly space of co-existing sounds. The performance will look at what it means to perform emotively through cultural and sonic connections, touching on ideas around record preservation and the conscious act of reclaiming lived narratives through collective sonic witnessing.

While tracing her practice in this conversation, Tran talks about the archives that voices hold and how they are affected by the atmospheres that signal and landscape geographies. For Tran, archives can exist in any form, and we can decide how our stories are shaped.

NTDHow did you first become immersed in the fields of art and performance?

MTGrowing up as a child from a refugee community in the U.K., I could not see how my world might fit into this predominantly white world. I was looking to break a model that would break the limitations imposed on me.

I witnessed my parents working in the garment industry growing up. Though it was terribly hard work—backbreaking, labour-intensive, and long hours on low pay—there was something in the agency of the hand, of making, of refusing to be dominated or devalued by a language, that excluded them purposely.

Through the language of their hands, they built a future that promised hope. The routine and the logic of making made sense to me. What did not make sense was how a person can be made vulnerable through the actions and exploitation of another person.

But perhaps more than anything it was the humour, wit, love, and determination I witnessed growing up in my margins that led a way for me.

My practice feels like a deliberate effort to detour. I find my skin fits better when I can fluidly move in and out of different spaces of knowledge-making. I am particularly interested in celebrating spaces at the margins of knowledge-making, to de-centre the centre. To move away from a conventional sense of what is valued as knowledge.

NTDWhat is your philosophy around art?

MTConforming to a superficial sense of value measured by a dominant Western understanding of what should be known leaves me with a feeling of being unknown and unvalued. At the heart of the matter, I make work that attempts to find multiple and alternative ways of worldmaking.

I find my skin fits better when I can fluidly move in and out of different spaces of knowledge-making.

As Donna Haraway says: 'It matters what stories tell stories / It matters what thoughts think thoughts / It matters what worlds world worlds / It matters what relations relate relationships.'

This thinking is also concerned with dismantling the prolonged systems of Western pedagogy that perpetuate the ongoing colonisation of knowledge. The systemically racist institution continues the work of empire by oppressing, erasing, and stigmatising knowledge made over centuries through balanced contact zones in communities and nature all over the world. I am interested in the abundance of knowledge-making systems in marginalised spaces, as contact zones for deepening emotional exchange.

My work takes, as its starting point, the history of how hierarchies of knowledge arose in parallel with the rise of the modern research university. The institutionalisation of research took place as an integral part of the colonisation of peoples around the world by European powers.

Two centuries of colonial dominance imposed a new world order in relation to knowledge. It systematically denied contributions from those who were not academics and elites from the Global North.

Over the centuries, the hegemony of a single, narrow approach to the production of what constitutes valid knowledge has benefitted some, but marginalised and excluded many, many more. The process has also been to the detriment of humanity's overall knowledge base.

NTDYour works are closely related to refugee communities. Can you expand on your collaborative relationship with immigrants?

MTI have lived experience as a refugee in a country that was not necessarily all-embracing of my arrival. I am interested in building relationships with communities and spaces that come to fruition in spaces of the margin. I celebrate life and everything that blooms in the margins.

The margin is no longer marginal but bursting at the seams with life and knowledge, love, and empathy. It is an abundant repository of embodied knowledge. It sits at the spine—a column at the edge.

I return to Bell Hooks and her wise words, 'speaking of a marginality one wishes to lose, to give up or surrender as part of moving to the centre, but rather as a site one stays in, clings to even, because it nourishes one's capacity to resist. It offers one the possibility of radical perspective from which to see and create, to imagine alternatives, new worlds.'

Transforming the marginal space from a space subjected, to a space that is a riotously unruly and fertile contact zone.

I have experienced diaspora spaces as sites of valuable learning and alternative models of critical knowledge creation. This reckoning has had a profound influence on my practice, producing ontologies that challenge prevailing epistemological orders and paradigms typical of institutionalised knowledge production and transmission.

Knowledge in marginalised spaces is not static; rather, it transforms, revitalises, and (re)constructs epistemologies and techniques to construct sites of pluriversal knowledge in a multiplicity of possible worlds.

I am interested in exploring emotional knowledge and how we can hang, perch, or rest our knowledge outside of the conventional canon of what constitutes a valued knowledge.

NTDYou are currently undertaking a residency programme in Sweden. How do you see this taking place in your practice? What challenges have you experienced with the programme so far?

MTMy recent research and work continue to explore sonic witnessing as a method to know the sticky sonorous qualities that immobilised political and emotional meaning. In parallel, I'm collecting sound as an unconventional archiving method to disrupt the traditional framework of archives.

My recent departure points lean into the complexity of sonic power as a constituent of agency, for if a sound can shape the sense of the possible, it must also wield a destructive capacity.

On this residency with Arts Inside Out in Sweden, I'm turning to reflect upon the weaponisation of sonic witnessing as the constitutive role of receiving sound and the mishandling of sound as a technique for sound cleansing.

On 15 September, I did a performance talk called A Salon with Moi Tran, for which I wrote the script for the event. It was a part of the residency and took place in Halland Art Museum. At the beginning of the presentation, attendees were asked to read short stories that were sealed in numbered envelopes and presented on a banquet table that everyone was seated at, in place of traditional seating arrangements at artist talks.

I have recently focused on the rise of radical white nationalist groups in Nordic countries, particularly Sweden. Here, I use music and sound interchangeably, as sound encompasses all forms of sonic experience.

In this case, I looked at the hijacking of songs to promote agendas of racism, hate, and hostility towards immigrant communities in Sweden. I am only at the beginning of this research journey, but I find this a very interesting provocation and I hope to expand my knowledge further.

At the heart of the matter, I make work that attempts to find multiple and alternative ways of worldmaking.

NTDYou will create a performance named Sign Chorus in Vietnam in March 2022. Can you tell me a bit about this performance and whether there is anything that you are especially excited about for this upcoming programme?

MTI am very excited about making Sign Chorus in collaboration with Nga Mai, who is the manager at Central Deaf Services (CDS) in Da Nang, Vietnam, and the brilliant students at the school.

Through my previous projects, I have focused predominantly on working with the capacity of sound and voice to communicate emotional knowledge. I realised I was neglecting other non-verbal, non-sounding forms of communication.

Sign language is a complex language used by over 70 million people across the world. In collaboration with Nga Mai and a local team, we will run a series of workshops with students to collect their stories, guided by the experienced teachers at CDS. In these workshops, we will encourage students to share their stories with us through sign language.

We will then collect their signing hand gestures to create a sign score, which the students will then perform. We plan to stage a public performance at Old Soul, a gallery space next to the school.

The performance will be documented and made into a film, and the sign score will be made into a printed artwork. The project will eventually be exhibited in Hanoi.

This work is being partly funded by National Archives U.K. and supported by the University of East London. We had planned to start making this piece of work in June 2021 to perform alongside the 'Shy God' community chorus, but unfortunately Vietnam went into a national lockdown.

NTDWhat are you currently working on and how has the pandemic affected your way of operating?

MTThe pandemic has certainly affected the way I think about the work that I want to make, need to make, and how I will make that work and with whom. But there are still so many human beings who are in the throes of this dangerous pandemic.

People losing their lives, loved ones, livelihoods, and homes. Some of the more powerful and wealthy countries can emerge from this pandemic; however, we mustn't forget the millions who share this earth with us who are still suffering. I am not sure if enough dust has settled for me to genuinely reflect on how this experience will change me as a human being and in turn as an artist. The change may take years to unfold and manifest in the conversations we make and the worlds we build.

I have been interested in researching sound and politics, concurrently to the documentation, archiving, and preservation of sound. I have been engaged with two key focuses: sonic encounters as a critical methodology to engage with sites of socio-political world-making, and performative acts of disturbing the conventional archive.

Civic Voice Archive is part of a larger body of work I am developing that includes performance, research, video, collecting, and writing. I envision this work will span the next few years of my practice, exploring actions to disturb the conventional use and narrative of the archive through 'fugitive' preservations.

I have started to think of an archive as a 'carrier bag', a theory introduced by speculative fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin. What we wish to keep safe or carry home to another place or time is placed in a 'carrier bag'.

In the seventies, the term 'Carrier Bag Theory' was used by anthropologist Elizabeth Fisher in relation to her research on human evolution. Fisher suggested that early humans' primary tool or 'cultural device' was not the knife or spear or club, but rather the containers they used to carry food home.

In 1988, Le Guin published her essay story 'The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction', in which she borrows this theory to develop ideas related to fiction and narrative theory, as gathering up and containing stories. Now I am borrowing this theory as a way to hold, gather, and bring back stories in the process of re-evaluating and collecting for archives.

Civic Voice Archive is an 'in-between' space of resistance—a space enriched by the agency of folklore, legend, ancestral wisdom, kinship, and refusal of erasure and extinction in the marginalised and diaspora space.

It aims to co-create an 'in-between resistance' in response to a lack of space for alternative protest to exist and be credited. Resistance, activism, and protest should not be a one-size-fits-all construct. It needs to be a conscious space that is able to contextualise.

'In-between resistance' declares a space of 'sonic witnessing' as resistance, in acts both large and small. High inequality inhibits participation, impacting self-value and mental health; communities living within structural discrimination lack privilege to protest visibly, with many fearing repercussions if arrested in open protest.

This work presents the possibility for a sustained, impactful resistance for people in vulnerable communities, where they can contribute actively and safely to an acoustic repository of lived experience.

I am interested in the abundance of knowledge-making systems in marginalised spaces, as contact zones for deepening emotional exchange.

Although this work has in its title the word archive, it is an intentional re-purposing of the word. It is a system that I feel inclined to re-purpose to refuse extinction and erasure, and to disrupt the process of what is valued by inserting open, unruly, un-ruled alternative methodologies of collection, preservation.

Through such a process, the archive is re-configured as an open common repository. I am preparing an exhibition to show this body of work with PEER gallery in Hoxton, London in 2022.

NTDWere there things that you particularly value or learnt in the process of collaborating with communities?

MTI have been working with communities in the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and the U.K. to collect video and audio recordings of their performances on home devices. What I am hoping to capture and create with the help of community contributors is an archive of 'feeling' through the collection of voices.

I have created instructions for the work to comply with Covid-19 restrictions to keep people safe and invite people to sing and self-record on a device that is easily available, such as a phone.

This archive celebrates the homemade video and relieves people of thinking that they need to create at high-production value. I am continuously rewriting this invitation to respond to questions and circumstances that people encounter in their experience of contributing.

I am open to exploring the final manifestation of this archive with the community. I imagine it to be open access and continuously open to new contributions. It will be a live and living archive.

To date, I have received audio and video recordings of prayers, originally composed for the archive of songs and poems and old folk songs from a spectrum of communities and generations. It is a fascinating and emotional exchange that I am very honoured to be part of. This archive will eventually become an online record and a live performance with aspects of video and audio installation.

The Civic Voice Archive aims to create safe agency for community contribution, of song and diverse forms of vocal expression as personal testimony to celebrate events and records that usually fall outside of mainstream archives and are often discounted of value by traditional systems. —[O]