Patrick Flores: 'Southeast Asia must be geopolitically unburdened'

Patrick Flores. Courtesy Singapore Art Museum.

Patrick Flores. Courtesy Singapore Art Museum.

The start of the new decade has seen a series of natural disasters around the globe. Bushfires in Australia have burned an area of roughly 10 million hectares; while ash dumped from the Philippines' Taal volcano has led to the evacuation of around 300,000 people in fear of an impending eruption. Meanwhile, as global temperatures rise, as do sea levels—impacting ecosystems, life, and cultural continuity.

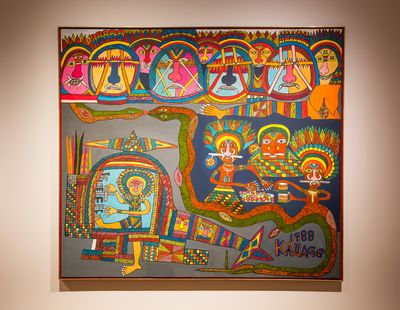

Continuity, at the 2019 iteration of the Singapore Biennale, Every Step in the Right Direction (22 November 2019–22 March 2020), means 'taking steps to consider current conditions and the human endeavour for change.' Led by Artistic Director Patrick Flores, the eminent Manila-based academic, curator, and art historian, the Biennale invites viewers to think critically about the role of art in impacting practice and discourse to enact real and tangible change in the world. Beyond posturing, aesthetics, and spectacle, Every Step in the Right Direction is a call to action, building upon Flores' extensive work in the academic field, with a regional focus on Southeast Asia in publications such as Painting History: Revisions in Philippine Colonial Art (1999), Remarkable Collection: Art, History, and the National Museum (2006), and Past Peripheral: Curation in Southeast Asia (2008).

Flores, further to receiving an Asian Public Intellectuals Fellowship in 2004, held a professorship in the Department of Art Studies at the University of the Philippines between 1997 and 2003, and in 1999 was a visiting fellow at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. He is the curator of the Vargas Museum in Manila, and adjunct curator at the National Gallery Singapore, with curatorial experience spanning projects such as Under Construction: New Dimensions in Asia Art (2000) at the Japan Foundation Asia Center and the Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery—a collaborative exhibition that involved seven other curators, including Mami Kataoka, Kim Sunjung, and Ranjit Hoskote, to present works by young artists from across Asia. In 2008, he organised Position Papers—a component of the 7th Gwangju Biennale focused on curatorial proposals by emerging curators; while more recently, in 2015, the Philippines returned to the Venice Biennale for the first time in 51 years under Flores' lead, showing works by Manuel Conde, Jose Tence Ruiz, and Mariano Montelibano III, among others.

In this conversation, Flores talks about the scope, trajectory, and outputs of Every Step in the Right Direction, his motivations for the edition, and the conditions of curating today.

TMI am interested in how your early experiences shaped who you are today—from the politics you advocate for, to the projects that you take on as a curator?

PFI grew up in the Visayas, which are a group of islands in the central part of the Philippines. My father was a government auditor and he took the family with him wherever he was assigned, until we settled in Manila in the late seventies. I think my exposure to the local culture of three islands was formative in my history of sympathies. I had to learn three languages, made new friends every two years, and was not so mindful about Manila as the centre of the country, and Filipino and English as privileged languages. I was happy to have been calibrated by these energies of province.

I believe that Southeast Asia must be geopolitically unburdened, released from its colonial and Cold War psychogeography.

My father was a lawyer and an accountant who was keen to discuss political life. My mother was a piano and organ teacher. I grew up in a household amid books and stray music. I remember I collected stamps and at one point went to church every day. I entered university the year Ferdinand Marcos was deposed by an uprising and a military coup. I studied Spanish first, before I shifted to humanities. I wanted to be a translator at the United Nations. My professors at the University of the Philippines, which takes pride in its activist history, taught art in the thicket of a complex social life; the professors were artists, critics, writers, and public intellectuals with copious commitments. So for me, the autonomy of art was always shared with the integrity of the social ecology.

TMThere are many views about what constitutes curatorial practice. Yours seems to advocate for an art historical view of cultural continuum, rather than a fixed historical perspective. What, in your opinion, should be considered 'curatorial'?

PFI was trained as an art historian, and art history as a discipline afforded me the long lens of context, as well as the deep intricacy of art's idiosyncratic form. I cherish this intellectual intensity and its sensitivity to the vast animate life that shapes it. You're right about the continuum, but there is also the timeliness, punctuality, and precision of discernment and articulation. On the other hand, there is unruliness, contingency, and indeterminacy. The art historical rests and thrives on this tension, which is something that the curatorial supplements with relationality and activation, and sometimes indescribable intuition or coincidence. Art cannot simply be assimilated, and yet it also cannot be ignored like some fatal attraction. The curatorial has to come to terms with both the necessity of resolve and the irritations of irresolution.

TMIn your opinion, what needs to change for Southeast Asia, and other parts of what we might define as the Global South, to level out the spectres of art history?

PFI believe that Southeast Asia must be geopolitically unburdened, released from its colonial and Cold War psychogeography. The contemporary and the curatorial can initiate this redistribution.

TMDo you think that the centre versus periphery binary is still a relevant lens for the art world to consider in relation to the distribution of resources, attention, and power relations, or is there a more dynamic approach to considering the global landscape?

PFThe centre-periphery binary is productive at a certain level. We must find a third moment, which reinscribes the binary and transcends it. Surely, the model of inclusiveness as a foil to exclusion and expansion has to mutate into a procedure of co-implication and, perhaps, in the tenor of David Medalla, an exploding galaxy.

TMCould you talk about the sixth Singapore Biennale, Every Step in the Right Direction, and how the title intersects with the Biennale's aims, publics, and context?

PFThe anthropologist Tim Ingold muses over this facture—of each step being part of a procession, 'not a building up from discrete parts into a hierarchically organised totality but a carrying on—a passage along a path in which every step grows from the one before and into the one following, on an itinerary that always overshoots its destinations.' Ingold contrasts 'iteration' with 'itineration', following Deleuze and Guattari, as something that is sinuous, not concatenated. When he describes the acumen of the axe-maker, he dissolves the objecthood of the material: 'In the hands of the skilled knapper, brittle flint becomes liquid, and is revealed as a maelstrom of currents in which every potential bulb of percussion is a vortex from which fracture surfaces ripple out like waves.'

In her own elucidation of The Rights of Others, in which the line 'no human is illegal' is a spectre, Seyla Benhabib recovers iteration as a repetition-in-transformation, and if it is characterised as democratic, it can refer to the 'complex processes of public argument, deliberation and exchange through which universalist rights claims and principles are contested and contextualized, invoked and revoked, posited and positioned'. Democratic iterations 'transform from what passes as the valid or established view of an authoritative precedent.' This is the ethical right that the Biennale fosters, and not the ideological right co-opted by a politics that thrives on prejudice. Benhabib situates the right in the context of 'universal moral respect and egalitarian reciprocity'.

The Biennale is entangled in complex relations, in well-being and duty. This ecology of relations, is, to quote Elizabeth Povinelli, 'neither a part nor a whole but a series of entangled intensities . . . The mangrove roots and reef formations cannot be given anything except a fragile abstract skin because those are themselves parts of other entangled intervolved "things" . . . Once the multiplicity of entities are oriented to each other as a set of entangled substances . . . this sense of entanglement exerts a localising force.'

And this is where we are at: the possible localising force of the Biennale through the steps taken within the intimate realms of the self and the worldly geopoetic terrains of an exuding ecology. As the art and the audience of the Biennale decide to take these steps as a deed of 'affirmative contingency,' the 'dynamics of towardness' begins, with 'its characteristic movements of inclining, approaching and approximating . . . in a lateral solidarity', in the words of Ranajit Guha.

TMHow does language connect to place for you?

PFIn the language of the Waray in the Philippines, the world around us is known as kalibutan. The word kalibutan also suggests 'consciousness'—an awareness that is rooted in a world that keeps on turning, from step to step, from detritus to life force. To call to mind a Biennale is to excite this prospect; it is to anticipate something unlikely from that which repeats, or from its parent species. As the repeating Biennale is anticipated, it is poised to be exciting, and it is strongly placed to speak to other sources that should render it ever more alert to the time and place of its being always in the making, like a problematique. To excite is thus to recover the fine traces of the Biennale's current locus, as well as the granular details of its dispersing.

All this seems to lay bare the Biennale as open, porous, and continuing. It might be more fitting to say it is tangled and responsive, committed to sympathy but likewise sensitive to certain methods of staking out positions in a world seduced by the common and the apparent.

TMCould you expand on Singapore as a site within broader global discourses? What does it mean to be curating a Biennale there now? How have artists responded?

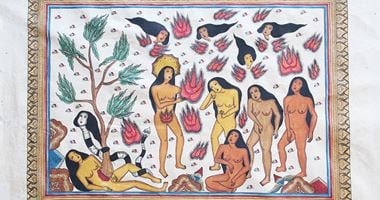

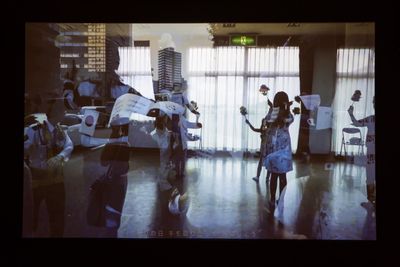

PFThe spectacularity of Singapore as a Potemkin metropolis in Southeast Asia inflects the intuition of biennial spectacle, which the 2019 edition tries to frustrate, even as the Biennale nevertheless tends to fold into the scenario. The imagination of a city as a veneer evokes yet another articulation of world-making in the dioramas of Singapore displayed at the National Museum of Singapore in the 1980s. These were made by woodcarvers from Paete, south of Manila. Hu Yun investigates the implications of the diorama as an intersection of craft and cosmology. He revisits Paete, films the mutation of a sculpted limb into a branch that is brought back to the clearing from where the wood has come, and contemplates a topography of contemporary Singapore, which has been delicately sculpted in ice by an artisan from the same province. He also investigates the new site of the dioramas at a primary school in Singapore called Elias Park, where he records the visions that the students glimpse from the dioramas.

The spectacularity of Singapore as a Potemkin metropolis in Southeast Asia inflects the intuition of biennial spectacle, which the 2019 edition tries to frustrate.

The diorama as a technology of seeing and appearance emerged contemporaneously with the photograph. The curator Nancy Spector, in her rumination on the photography of the Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto, links up the diorama and the photograph through Louis Daguerre, who invented both apparatuses, and their roles in the production of the 'reality of simulation' in 'prosthetic environments'. Like Sugimoto's excursus into the uncanny ties between photography, wax, and taxidermy in museums, Hu Yun parses the discursive fallout of the diorama experience.

The region of Southeast Asia is gleaned amid restive waters: the South China Sea, the Pacific Ocean, and the Indian Ocean. Curators thread the world through these channels and take them to routes worth re-charting, such as the European colonial theatre, trans-Pacific trade, the Austronesian movement, the Silk Road, the piratical Sulu Zone, the 'ungovernable' Zomia, and so on. Southeast Asia thus thickens as it extends, congeals as it alters. I was personally interested in the 'Americas' as a geography that indexes conquest and democracy and with which the Philippines has a particularly equivocal relationship.

TMNow that the exhibition is open, can you share some of your favourite conversations and moments that you've had with artists and publics?

PFI am a bit curious about how it has been reviewed. It is interesting how the art world press comes to it with some default expectations around biennial-making. I anticipated a more open mind to reciprocate the different method we are contemplating here, but it seems habits harden over time. Everything is instructive, so it should be fine, except that the ethos of reviewing has become unproductive, as the reviewer tries too hard to pin or take down with a modicum of self-doubt and speculation. It's a bit of pseudo-spectacle in and by itself. It's sad how an organism of so many moving parts like an exhibition gets reduced to adjectives like good or bad, or best or worst.

TMOn a practical level, how do you manage your various curatorial and academic roles? Can you talk us through the scope of each of these and what they entail?

PFI teach art history, run a university museum, curate independently, and do scholarly and curatorial research. I think these roles interpenetrate and inflect each other.

TMI've noticed that you are quite generous in your capacity for mentorship. This is evident through the curatorial team that you surrounded yourself with at the Biennale. Can you elaborate on how and why you approach mentorship and intergenerational sharing with such passion and fortitude?

PFI like to learn from young curators. They think and do things differently. If the schooled art historian has this concept of a 'period eye' to capture style or meaning, the curator today has an attentiveness to disarticulate form and render it vulnerable to reiteration formlessness.

TMWhat do you hope that audiences take away from the Biennale?

PFThat the Biennale is an invitation for us to reflect on the need to take a step towards what is personally and collectively decided upon as the right direction.

TMWhat are your hopes for the future of art and discourse?

PFFor discourse to be an affective inspiration and for art to be a sign of a volatile, sensible world of so many strange species. The ethical and the geopoetic should coalesce. Derrida once said that to be confronted with an impasse is necessary to decide to have a future. —[O]