Sunjung Kim’s Real DMZ Project Interrogates the North and South Korea Divide

Sunjung Kim. Photo: Jung JM.

Sunjung Kim. Photo: Jung JM.

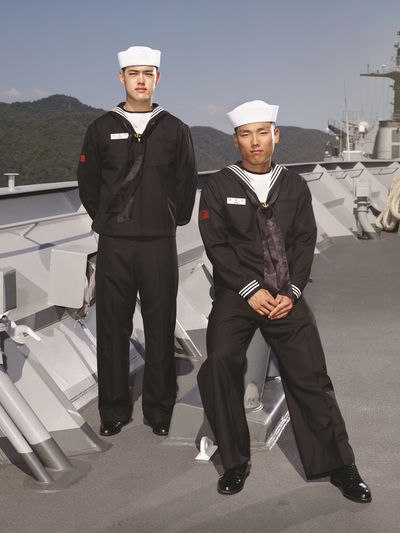

Ongoing since 2012, the Real DMZ Project interrogates the demilitarised zone (DMZ) between North and South Korea through annual, research-based exhibitions that bring together the works of Korean and international artists.

Sunjung Kim, the independent curator behind the project, conceived the idea of exploring the DMZ while curating Japanese artist Tatsuo Miyajima's solo presentation 38 at Seoul's Mongin Art Center in 2008. Revolving around the theme of borders, the exhibition included photographs taken at Imjingak and the Taepung Observatory, sites near the DMZ, that feature individuals with numbers painted on their bodies, such as 3 and 8 to allude to the 38th Parallel that divides the Korean peninsula in two. Kim envisioned a ten-year project, now known as the Real DMZ Project, that would accumulate artworks and archive materials about the complexities surrounding the DMZ.

The first Real DMZ Project assumed the form of an exhibition, which was held in Cheorwon—a small county in Gangwon Province that was once one of the main sites of collision during Korean War, a third of which lies in the DMZ today. As a number of artworks in this iteration proved to be difficult to access, such as German artist Dirk Fleischmann's lavish chandelier (Chandelier 363-931, 2012), which was located in an underground tunnel, the following exhibitions evolved to become more accessible.

For three consecutive years from 2013, the Art Sonje Center in Seoul hosted exhibitions and artist talks. In 2014, the inaugural artist-residency programme took place in Yangji-ri, a former propaganda village established by the South Korean government in the 1970s. In 2015, the exhibition, REAL DMZ PROJECT 2015: Lived Time of Dongsong (13 August–23 August 2015), moved to Dongsong, a town populated by residents living in the vicinity of the DMZ and soldiers on leave from the border.

That same year, the Real DMZ Project also began to exhibit internationally. With Slought, the Department of English and the Cinema Studies Program at the University of Pennsylvania, Kim organised Cold War, Hot Peace (26 February–12 April 12, 2015), a group exhibition of works by artists who had participated in the project. In 2017, a selection of video works travelled to Denmark as part of The Timeshare Project, a two-month international exchange programme during which Kunsthal Aarhus hosted exhibitions from five other institutions. Works by eight Korean Project alumni were then exhibited in The Real DMZ: Artistic Encounters, a group exhibition at New Art Exchange in Nottingham, U.K., in 2018 (27 January–15 April 2018). Most recently, the large-scale exhibition DMZ—featuring works of 61 international artists—at Cultural Station Seoul 284 (21 March–6 May 2019) in Seoul included artworks and archival materials from the project.

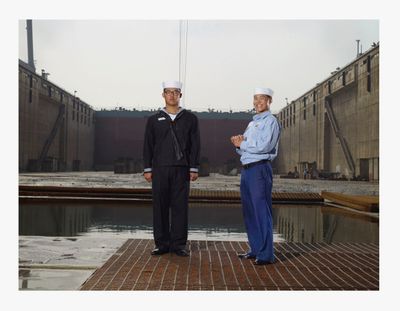

Negotiating Borders is the latest Real DMZ Project exhibition, hosted at the Korean Cultural Centre UK in London (1 October–23 November 2019). On view will be existing and newly commissioned works by Korean artists, among them Joung-Ki Min, Minouk Lim, and Yeondoo Jung, that examine the multifaceted perceptions of the DMZ and its position in the inextricable history and present of North and South Korea. Despite its location in the middle of the Korean peninsula, for example, the DMZ is a mystery to the majority of Koreans on both sides.

Kim's interest in developing experimental exhibitions is well established. In 1995, she organised Ssack, a seminal group exhibition that took place in an architectural hybrid of traditional Korean and Western-style architecture, respectively known as hanok and yangok in Korean, that stood where Art Sonje Center is now located. Departing from the trend at the time in Korea to exhibit existing work, Kim produced new, site-specific works in conversation with the participating artists. Among them were Bahc Yiso, Choi Jeong Hwa, and Lee Bul—some of the most representative artists of Korean contemporary art today.

Kim's following projects over the years demonstrate a penchant for prodding conversations about new ways of producing and experiencing art exhibitions, while addressing social and political conditions of the contemporary world through art. During her time at the Art Sonje Center, where Kim acted as chief curator and deputy director between 1993 and 2004, she became known for curating forward-thinking exhibitions. In 2005, as the commissioner of the Korean Pavilion at the 51st Venice Biennale (12 June–6 November 2005), Kim deviated from the more common format of a single presentation in favour of the group exhibition Secret Beyond the Door, which showcased works by 15 Korean artists. That same year, she founded Samuso, a curatorial office with a mission to further the practice of exhibition-making, which leads the Real DMZ Project (2012–ongoing).

In this Ocula Conversation, Kim discusses Negotiating Borders, the Real DMZ Project, and her other projects, both previous and upcoming, including her current position as the president of the Gwangju Biennale Foundation since 2017.

SPThe Real DMZ Project is now in its seventh year. What were some of your goals when you first started the project and how have they been met? What new goals have emerged in the project's evolution?

SKI started the Real DMZ Project with hopes to raise awareness about the division of Korea, the complicated border issues, and their influences on our everyday lives. When the Korean War was halted abruptly, the Korean Armistice Agreement also created the DMZ, which divides the peninsula into two distinctly different political systems. A military standoff along the DMZ still continues to this day. The impacts of the division and the continuing military and ideological conflicts have been immeasurable. In South Korea, while the economic and industrial development progressed rapidly, the traumas caused by the war and division have become internalised as part of our society and individual lives.

Realising how much we had learned to forget rather than remember about the division and the tragic war that is still pending, I thought that raising awareness and bringing the issues to our everyday consciousness would be important and necessary. Since I started the Real DMZ Project, I have been able to see the number of artists working on Korean border issues increasing. Of course, there have always been artists interested in the division of Korea, but as I develop the project through conversations and collaborations with artists and researchers, I can see more and more artists beginning to actually address and explore the border issues from different perspectives in their research and creative works. My new goal is to be able to curate an exhibition in North Korea.

SPIn the past few years, the relationship between North and South Korea has changed considerably. In what ways have these developments influenced the Real DMZ Project?

SKSince the historic inter-Korean summit of 2018, there have been unprecedented attempts at reconciliation between the two countries, and that has led me to have new hope for the Real DMZ Project—to curate and mount an exhibition in North Korea, as mentioned earlier. Given North Korea's strict restrictions on art exhibitions, that might be only a dream for now. But whether possible or not, that is part of my long-term plan.

SPHow does Negotiating Borders differ and connect to previous iterations of the Real DMZ Project? Are there particular artists, artworks, or theories that have influenced the ideas that fed into this particular exhibition?

SKArtists like Kyungah Ham and Minouk Lim, who have participated in previous iterations, will exhibit their works in new configurations or different formats. For example, Minouk Lim is creating a new installation that encompasses her performance and installation (Monument 300—Chasing Watermarks, 2014) that took place in the old Waterworks Bureau in Cheorwon.

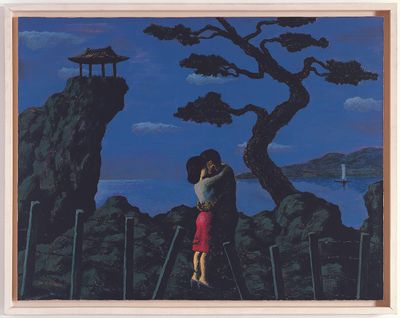

Negotiating Borders seeks to offer glimpses of the Korean border's past, present, and future. The exhibition includes, for example, painting works from the 1980s and 90s by relatively older artists like Joung-Ki Min and Kim Jung Heun, as well as an archive of photographs of the border areas since the 1950s, comprised of both public records and donations from ordinary citizens, which are useful resources that engage us to look into Korea's history since the war. We will also exhibit works that constitute fictional scenarios or proposals for the DMZ's future. For example, architect Seung H-Sang's bamboo shelter for birds is a contribution to Dreaming of Earth, the collaborative project, initiated by artist Jae-Eun Choi, that speculates about constructing structures between North Korea and South Korea without destroying the DMZ's natural environment.

Also on view will be archive materials from the 1988 exhibition Project DMZ, curated by Kyong Park at New York's Storefront for Art and Architecture (22 November–18 December 1988), which invited artists, architects, and thinkers to imagine how the DMZ might be used for purposes other than military and political means. The past, present, and future of the DMZ are explored and imagined from different points of view, as such. In brief, I hope this exhibition will provide the opportunity to experience a remarkable variety of approaches, methods, perceptions, interpretations, and stories towards and about the DMZ.

SPHow different is it to exhibit The Real DMZ Project outside Cheorwon, where the artists' residencies and research take place, versus elsewhere in the world, like Seoul and now London?

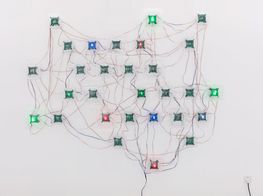

SKWhen exhibitions are organised in Cheorwon, the aims include bringing people to witness and experience the region as well as the exhibitions. In comparison, the exhibitions mounted outside Cheorwon tend to pay more attention to addressing political, social, and historical issues related to the division and the border. In these exhibitions, many artists have explored various kinds of 'borders' and 'distances'. For most of us in South Korea, North Korea is a forbidden land and the strict prohibitions and ideological conflicts have created a certain psychological distance towards North Korea. Addressing the layers of such complicated distances between South and North Korea, Kyungah Ham's work consists of embroidery works made by North Korean seamstresses, who, contacted indirectly through brokers in China, embroider quotations from South Korean pop songs and mass media in camouflaged designs so that they can escape North Korean censorship.

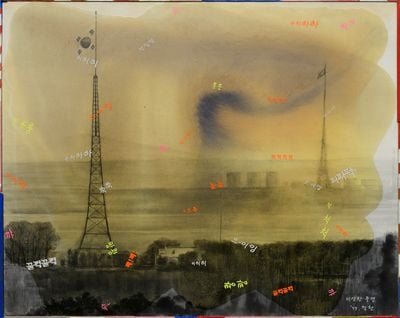

Seung Woo Back employs highly idealised, propagandistic images of North Korea that he found in Japan, and further manipulates them. Hayoun Kwon's video 489 Years (2016) reconstructs the DMZ space following the oral testimony of a former soldier with whom she conducted an interview. Onejoon Che, who participated in the New Art Exchange exhibition but not in the London exhibition, has conducted his research on North Korea in Africa, where North Korea has been constructing monuments and buildings since the 1970s. As such, to talk about and explore 'there' from 'here,' we are bound to work through and work with the layers of prohibitions.

SPThe theme of 'borders' seems to be an ongoing concern in your projects, with the 2013 Real DMZ Project that was titled Borderline, and Borders as Specters for the 2018 iteration, not to mention that the title of last year's Gwangju Biennale was Imagined Borders, inspired by Benedict Anderson's 1983 book Imagined Communities. How did you begin to develop this thematic focus?

SKThe Real DMZ Project has been a project of research as much as it has been a project to produce art and curate exhibitions. Since its inception, the Real DMZ Project has organised seminars, lectures, and conferences by inviting experts in a variety of fields including history and sociology, and they have provided us with a wide range of scholarly perspectives through which to look at and understand issues related to the DMZ.

My interest in Anderson's theory is traced back further in time, but if I have to name sources of inspiration for my continuing concern with the theme of borders, I should first point at the forum organised by the historian Han Hong-koo in conjunction with the Real DMZ Project in 2013; he invited scholars of humanities to explore the relationship between Korea's division and the changes in our daily life by focusing on what he identified as five essential components of life: mind, relating to psychological borders between not only the South and the North but also between the East and the West; land, relating to people in reclaimed areas; iron, to reference war; rice, relating to postwar policies regarding hunger; and water, to reference river politics. Park Chan-Kyong, the artist who has addressed various inter-Korean issues from different angles—his works and my conversation with him have also been influential during the formative years of the Real DMZ Project.

SPBorders suggest movement and by extension migration. Could you briefly talk about your work as a curatorial advisor for Migration Narratives in East and Southeast Asia, a project about the relationship between art and migration? What can we expect from the the exhibition when it opens at Gwangju Asia Culture Center in November 2019? Is migration a theme you plan on exploring further in your practice?

SKMigration Narratives in East and Southeast Asia is a project that examines the narratives of migration from artistic and curatorial perspectives. Participants from across Asia have produced artworks and exhibitions based on their research and exchange of ideas through podium discussions that took place in cities like Berlin, Seoul, and Gwangju. My role was to provide advice and knowledge related to curating and art and exhibition production. Their exhibition opened in Ulaanbaatar last June, and is scheduled to open in Gwangju's Asia Culture Center this November, which will be a larger iteration. Migration is not really my area of expertise, but I acknowledge that it is a very important and serious issue that we all must face and do something about. I am curious to see what kinds of resonances and messages the exhibition will deliver to the audience in Korea.

SPProjects like Migration Narratives in East and Southeast Asia suggest international networking, which you have done quite often as a curator over the past years. The 2012 Gwangju Biennale (7 September–11 November 2012) was a co-curation between six Asian and Middle Eastern female curators; for last year's Gwangju Biennale, you also chose the multi-curator system. What do you consider to be the advantages and disadvantages of co-curating? Do you prefer to work alone or as a group?

SKThere are more advantages than disadvantages when you collaborate. Teamwork is difficult, of course. But working as a group is always better, because in the process of collaboration you learn so many new things from one another. Curating is more than just exhibiting; for me, curating is a process of learning. The first time I learned about the value of co-curating was while I was co-curating the Under Construction exhibition, organised at the Japan Foundation (7 December 2002–2 March 2003), with curators such as Kamiya Yukie from Japan, Patrick D. Flores from the Philippines, and from Thailand, among others.

SPIn addition to your international collaborations, in Korea you also worked as the artistic director of Platform Seoul (2006–2010), which had a different theme and location each year in Seoul and aimed to explore alternative modes of exhibition-making. The third edition in 2008, I Have Nothing to Say and I Am Saying It, transformed the former Seoul Train Station into a site of exhibition that examined theatricalities in art, while the final edition, Projected Image in 2010, was a film programme at the Art Sonje Center that resembled a film festival. It is now almost a decade since Platform Seoul—can you briefly reflect on the project and how it has affected your approaches to exhibitions that followed?

SKLooking back on the Platform Seoul project, I think it provided me with a turning point in my curatorial career; through the project, my concerns shifted towards social conditions, and that eventually led me to initiate the Real DMZ Project. Prior to the Platform Seoul project, my curation tended to put more emphasis on collaborating with artists to produce new works. But through working on the Platform Seoul editions, I developed interests in sociopolitical issues and contexts, for example, in the social space and the questions around art's role.

Does art have a social role? How does it operate? What does it mean to be public? How does an exhibition forge relationships with the space, and with the audience? I wanted to explore these questions through curation and exhibition-making. I also became more interested in 'sites' in my approaches to exhibitions. Curating in unusual sites, for example; utilising ruins, abandoned buildings or unused spaces, and exploring the sites' unique characteristics through curation—these approaches have become part of my practice.

SPIn Korea, many of your exhibitions have been staged in decommissioned buildings, such as the former Seoul Train Station for Platform Seoul 2008 or Ssack, which you curated in 1995 in a building that was scheduled to be demolished to make way for the Art Sonje Center. Is there a site in Korea that you would like to engage with in the future, but have not had an opportunity to do so?

SKAs mentioned, I would love to curate in North Korea. I hope I will one day be able to curate a contemporary art exhibition in Pyongyang or Kaesong, especially on sites that are unusual or meaningful; mounting a site-specific exhibition would be great.

In the case of South Korea, there are many buildings that people do not know what to do with, and I would love to have the opportunity to utilise and transform them into exhibition sites. Previously I have engaged with modern architectural buildings, such as the former Seoul Station building and the former site of the Defence Security Command of South Korea, known as Gimusa, where the National Museum of Contemporary Art (MMCA) Seoul building currently stands. I haven't yet worked with traditional buildings or sites. I almost had the chance to curate in Haeinsa, the beautiful temple especially known for housing the Tripitaka Koreana, the Buddhist scriptures carved on approximately 80,000 wooden blocks, though the project didn't happen in the end. I would really appreciate curatorial opportunities to engage pre-modern traditional Korean architectures that embody the era's specific ideological and spiritual significance, such as Buddhist temples or Seowon—Confucian educational institutions built during the Joseon Dynasty.

SPWhat future plans do you have for the Real DMZ Project?

SKFor the Real DMZ Project, I'm in discussion with a few artists currently. In particular, I am looking for funds and a site to construct Tobias Rehberger's house design contribution to the 2018 Real DMZ Project. Titled Duplex House, Rehberger's proposition is a three-storied residential building for two Korean families, one from North Korea and the other from South Korea. We are working to put the design into realisation. Before Korea's reunification, the house will be inhabited only by a family from South Korea.

On 20 May 2019, as part of the Real DMZ Project, the Danish artist trio SUPERFLEX installed two swings as part of One Two Three Swing! in front of Dora Observatory in Paju, near the DMZ. We really hope to be able to install their swings in North Korea one day. It took about two years for us to realise the SUPERFLEX installation in Paju. Some projects can easily take five years, given the strict restrictions in the region. I can't wait to see the swings installed in North Korea, however long that may take. —[O]